This is the last in our series of blogs marking the contribution of Commonwealth nations to the Somme offensive a century ago. Today – 18 November – was the last day of the last battle of that four-and-a-half month struggle; a battle named after another river and tributary of the Somme, the Ancre. This blog will explore the contribution made by the 4th Canadian Division to that fight.

Since the beginning of the Somme battles in July, Commonwealth and French armies had made limited gains north and south of the Somme river. After the initial, massive thrust of the first phase had been checked by German defences at some cost, the battles of early autumn were comparatively constrained. Nonetheless, their tempo was dictated by the promise of exhausting the reserves of German manpower and exploiting the weaknesses in their new, hastily constructed positions. As a series of battles running from July to November, however, the offensive naturally experienced most of the seasons and, with them, the full gamut of Northern European weather. This became particularly problematic as autumn rolled on, and the prospect of sustained operations into the winter gradually diminished; they were to continue, weather permitting.

By the middle of October rain and mist were obscuring the battlefields and making living conditions extremely trying for soldiers. These conditions also limited the scope of artillery and aircraft. Without the ability to survey the ground from above and with gun barrels worn from months of continuous action, counter-battery fire (engaging German artillery) and accurate bombardment of German defences were at times difficult. Nonetheless, as a prelude to the final action and after a number of delays, what became known as the Battle of the Ancre Heights was fought between 15 October and 12 November. This was an effort to secure Stuff Trench and Regina Trench, thereby occupying the continuation of the Thiepval Ridge defences and the high ground around the River Ancre. After a number of false starts thanks to waterlogged ground and frequent rain, the ridge was eventually captured by 21 October with small, consolidating actions taking place into the next month and finishing on 11 November.

These earlier battles had seen the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions heavily engaged before being relieved on 17 October. The recently arrived 4th Canadian Division had joined the battle on the following day, gaining a foothold in Regina Trench on 21 October and completing its capture in the early hours of 11 November. The next and final phase of the offensive would begin again in two days, with the 4th Canadian Division playing a central role. Its objective was to capture the newly-dug Desire Fire Trench and Desire Support Line Trench to the north of Regina.

The Canadian contribution to this action began in the early hours of 18 November. The first snow of the year had fallen in the night on the firmer ground, which promised to make going easier for the infantry after weeks of rain. A small rise in temperature at dawn, however, saw ice turn to slush, the snow to sleet and finally to rain. To make matters worse, the snow unhelpfully obscured the battlefield and the enemy. As the official history would later state, “more abominable conditions for active warfare are hardly to be imaged” (Military Operations France and Belgium 1916, p.514).

Nonetheless, at 6.10am, in the limited visibility of that November morning, the artillery and machine gun barrage opened to support the advance. In part, this was to be a rolling barrage, falling 200 yards in front of Regina Trench for four minutes, before rolling forwards at the rate of 50 yards per minute until it merged with the standing barrage already falling on the Desire Support Line. At 14 minutes from zero hour, the barrage would lift from the main objective and settle 250 yards north as a defensive measure. By shifting in this way, the artillery was – in theory at least – doing some of the infantry’s fighting for it, allowing it to storm and occupy the enemy’s trenches before the surviving defenders could reorganise.

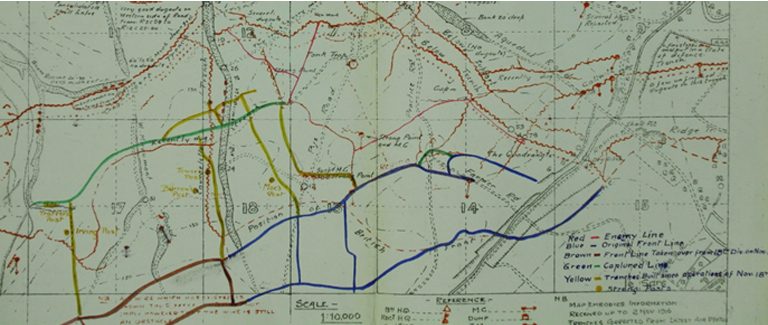

The attacking battalions had been in or in front of Regina Trench before zero hour waiting for the barrage to start, each arranged in 4 waves; the 10th brigade operating on the right, the 11th (with the 38th Battalion of 12th Brigade attached) on the left. The assault began in whirling sleet which meant many lost their way initially, although by 9.20am the 11th Brigade was reporting success in having gained its primary objective, with two battalions – the 38th and 87th – establishing a foothold in Grandcourt Trench beyond (see brown arrows).

WO 95/3900 extract from 11th Brigade Headquarters diary

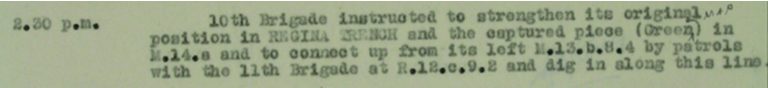

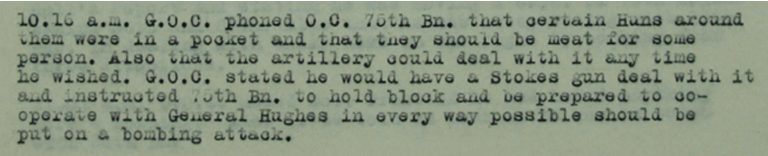

However, all was not so well with 10th Brigade on the right of the operation. The left-hand attacking company of 50th Battalion suffered considerable casualties when confronted by machine gun fire from a German strongpoint, the exact position of which was not known, and artillery fire from the Neighbourhood of Pys to their north-east. At the time their sister brigade was reporting success, elements of the 10th Brigade were falling back on Regina Trench. By early afternoon, the 10th Brigade was ordered to strengthen its position in Regina Trench – its starting point – and link up the small section of the new German line still in their hands (see small green line on the right of the map).

WO 95/3880 General Staff Headquarters diary, 4th Canadian Division

WO 95/3880 General Staff Headquarters diary, 4th Canadian Division

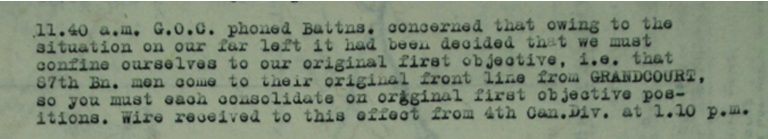

The uncertain situation on the right and left of the more successful elements of 11th Brigade potentially left their flanks exposed, so the decision was made to pull back the outposts in Grandcourt Trench and to dig in on the original objective. By 3.30 in the afternoon – presumably with the light beginning to fade – an end was called to the battle and wider Somme campaign, with the Canadian brigades receiving instructions for the Division’s defensive arrangements on the captured line.

WO 95/3900 extract from 11th Brigade Headquarters diary

![WO 95/3895 10th Brigade Headquarters diary: “the attack as far as the 10th CIB [Canadian Infantry Brigade] was concerned was not successful.” Unfortunately the promised appendix does not seem to have survived](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/01153126/Untitled-t4-768x67.jpg)

WO 95/3895 10th Brigade Headquarters diary: “the attack as far as the 10th CIB [Canadian Infantry Brigade] was concerned was not successful.” Unfortunately the promised appendix does not seem to have survived

WO 95/3900 example of communications flowing from Divisional HQ to 11th Brigade Headquarters

Thus ended the infamous Somme campaign, 140 days after it began, in snow and sleet rather than summer sun. Though relatively insignificant in comparison to earlier events, the Battle of the Ancre did hold some importance for the British Expeditionary Force as well as for the commander of the Fifth Army and this section of the front, General Sir Hubert Gough. Success in November ensured that the Somme offensive finished with a victory, albeit a limited one, which provided a much needed reputational boost for senior command and their direction of the war. The 4th Canadian Division’s contribution to that victory was clear but it came at a cost, in part due to the awful conditions endured. As the official history concluded, “to the sheer determination, self-sacrifice and physical endurance of the troops must be attributed such measure of success as was won” (Military Operations France and Belgium 1916, p 514).

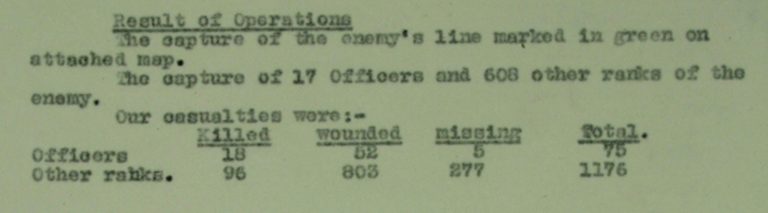

WO 95/3880 Divisional casualties as reported by the Headquarters, General Staff war diary, 4th Canadian Division

Despite its reputation, the Somme campaign was neither an exclusively British fight nor an unbroken series of failures. As this series of blogs has demonstrated, not only was it fought in coalition with the French, it also drew heavily on the forces of the Commonwealth. Far more long lived than the bloody failure of 1 July, later battles on the front showed that, with limited objectives and the application of novel technologies, a degree of success was possible. Breakthrough, however, would not come in 1916; in fact, it would not come for another two years. Though no answers to the deadlock were found, some lessons were learned; lessons that would be applied with mixed results to the BEF’s next major offensive at Arras in the spring of 1917.

Explore some of the other blogs in this series: the Battle of Albert, the mounted action at High Wood, the Battle of Delville Wood and the Battle of Flers-Courcelette.

I have read that the battle covered the 19th November.

Thanks for reading David.

In common with all the fronts, there were very few moments of complete inactivity. There were certainly counter-attacks defeated on 19 November as well as some repositioning of forces, but it’s generally accepted that – in the eyes of British command – major offensive operations ceased on the 18th.

[…] techadmin on November 18, 2016 Battle of the Ancre2016-11-18T11:31:37+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

I am trying to find any info re a soldier from Fleur de lys,nfld. who served in World WAR One in France and am having great difficulty finding anything on the websites in Canada and am wondering if there might be anything in your ARchives since Nfld. was a colony of Britian at that time. He enlisted in 1918, and the family understands that he fought in France .His name is George William Tobin and his age at enlistment was 26.

Hi Vivian,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell