The British-led Battle of Amiens, fought between 8 and 12 August 1918, was a decisive Allied victory. It marked the beginning of what has come to be known as the Hundred Days offensive, which saw the collapse of the German army on the Western Front. This is the first of three blog posts covering that advance: the prelude, the battle and its consequences.

Despite the confidence with which the battle was launched, and its ultimate success, its significance was born out of the first of the German spring offensives in March 1918. With manpower released from the Russian collapse on the Eastern Front in 1917, these were the last significant attacks made by the German armies in any theatre. In an attempt to divide British and French forces, capture points of strategic importance and force a favourable peace, these German offensives marked a final effort to break Allied resolve. One significant objective had been Amiens.

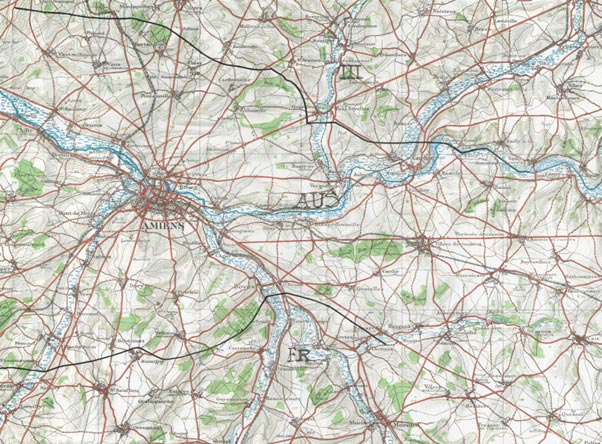

Although militarily unimpressive and of little political significance, Amiens held strategic value as the principal rail hub of the Allied war effort. Holding the main railway communications between the British base at Le Havre and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) front, as well as the direct routes between the northern ports and Paris, it was the hub through which flowed the means of feeding, arming and reinforcing Commonwealth and French soldiers. [WO 95/434/1]

The first of these German assaults pushed towards Amiens and fell upon the British Fifth Army, which was still in the process of completing its defences. German advances were alarmingly fast and allowed them to push beyond 60 kilometres in places; however, on the Somme the offensive eventually stalled on the high ground at Villers Bretonneux. Around 15 kilometres in front of Amiens, this position changed hands a number of times until a determined counter-attack by Australian units secured the line. [WO 95/434/1]

By the end of April, the threat of Allied collapse had largely passed, while French-led counteroffensives on the Marne in July had finally and convincingly ended the German advance. Failure to break through Allied lines had left the German army in possession of a number of salients, the largest of which jutted out towards Amiens.[ref]Salient – a bulge in the front line jutting into your enemy’s territory, usually the result of localised success in battle. Though holding more ground, that ground will be exposed to ‘enfilading’ fire – allowing your enemy to engage you from the sides as well as the front, and making rear areas more vulnerable.[/ref]

Now operationally vulnerable and exhausted by these costly efforts, the Germans could do little more as American soldiers and vast quantities of materiel poured into the theatre.

The Australians, now in force between Villers Bretonneux and Morlancourt, also began to wear down their enemy. As Fourth Army HQ later commented:

The Australian Corps turned the tables… and obtained by the beginning of August a mastery over the enemy such as has probably not been gained by our troops in any previous period of the war. [WO 95/434/1]

With resources in his favour, and inspired by recovering morale, Marshal Ferdinand Foch – supreme Allied commander since March 1918 – planned a series of offensives that would keep the German army under pressure, allowing it no time to recover. The battle at Amiens was designed as the first step in irreversibly breaking German resistance.

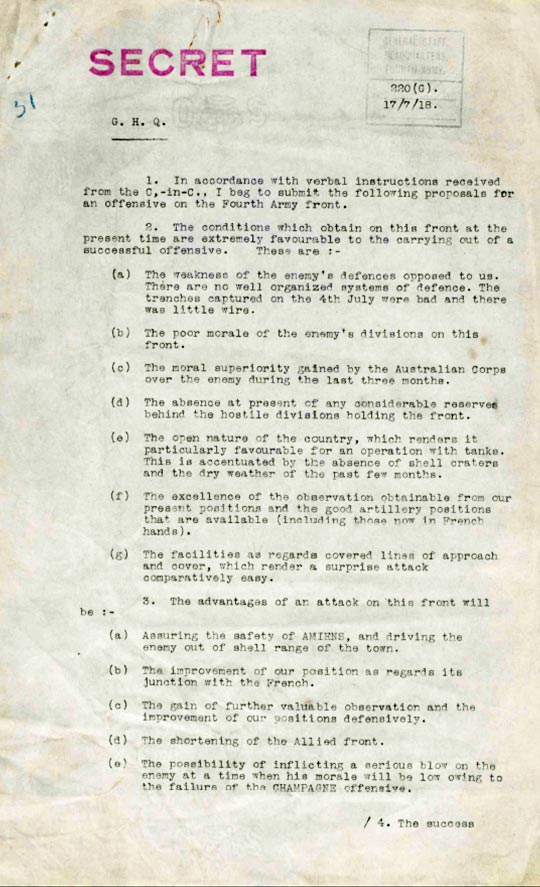

Fourth Army memo signed by Sir Henry Rawlinson, issued 17 July 1918. WO 95/437/2, Proposals for Offensive on Fourth Army Front

Fourth Army memo signed by Sir Henry Rawlinson, issued 17 July 1918. WO 95/437/2, Proposals for Offensive on Fourth Army Front

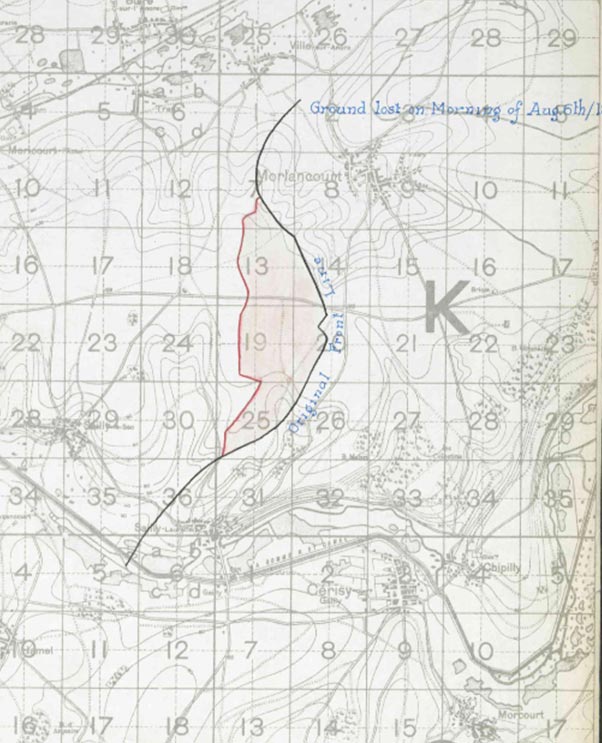

The task fell to General Sir Henry Rawlinson, now commanding the reformed Fourth Army, which occupied the sector straddling the River Somme. This was made up of British III Corps, the Canadian Corps and the Australian Corps, along with most of the Tank Corps and the Cavalry Corps. Further south of the Somme, two French corps – XXXI and IX – were to play a supporting role in the battle. By August, not only had the Fourth Army amassed more than 2,000 pieces of artillery, it had more tanks and armoured cars at its disposal than had been seen in any previous battle, and nearly 2,000 British and French aircraft. This diverse commonwealth and French force, supported by vast quantities of technology, brimmed with confidence – a characteristic now lacking in its opponent. [WO 95/434/1]

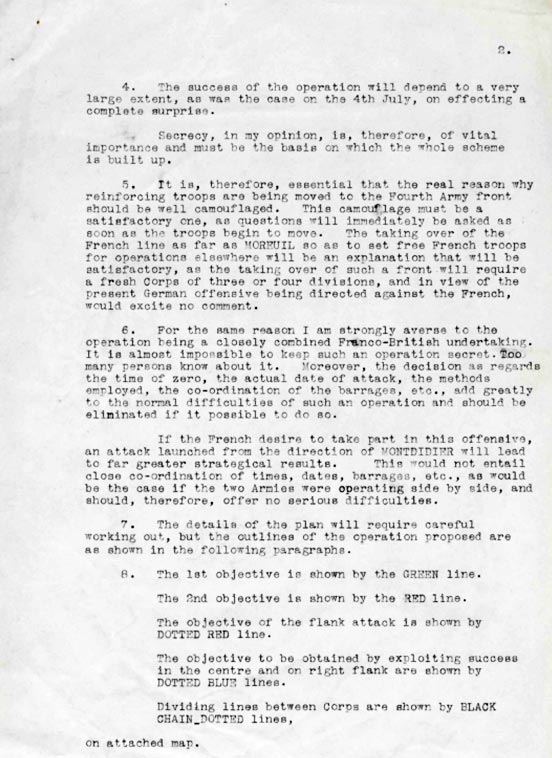

Note on secrecy pasted into officers’ and soldiers’ pocket books in advance of operations. WO 95/437/4, Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918.

Above all else, great weight was placed on the importance of secrecy and misinformation during planning – in particular the move of the Canadian Corps south from First Army. It was recognised for its central contribution to recent offensives, and its presence would have signalled an imminent attack. Tanks, too, were concentrated and camouflaged in the villages of the Somme Valley, while all troop movements were conducted at night. Brigade commanders were not informed of the true plans until 4 August – four days prior to the attack – while nothing would reach the men in the firing line until 36 hours prior to zero.

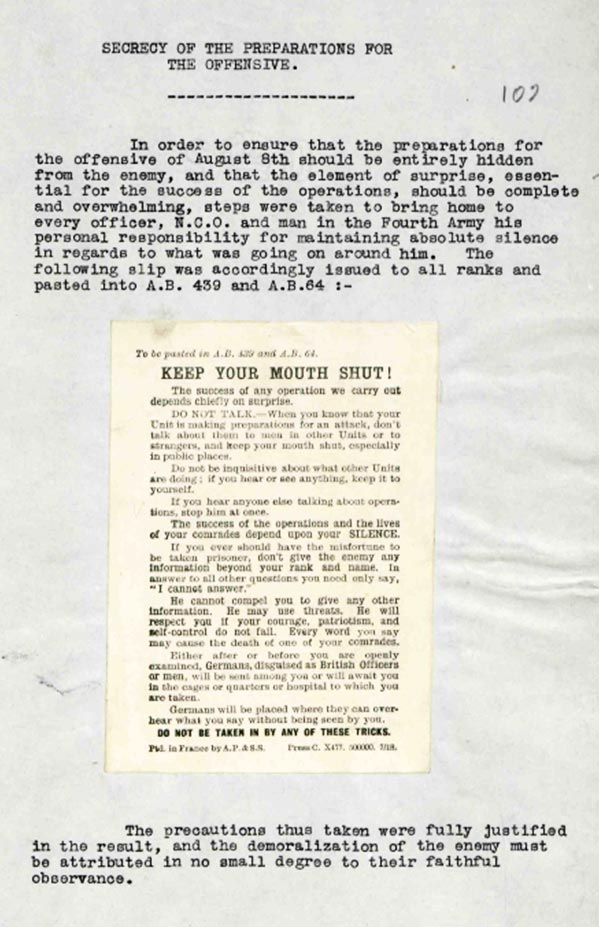

Ground lost on 6 August to German attack against 18th Division. WO 95/437/4 – Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918.

A limited German attack on 6 August, directed towards British 18th Division north of the River Somme, caused some concern about the enemy’s intentions. Nonetheless, Zero Hour was fixed for 04:20 on 8 August: approximately one hour and ten minutes before sunrise. The attack was to be spearheaded south of the river by the experienced Canadian Corps and Australian Corps, alongside the bulk of the tank battalions. In an effort to achieve surprise, their combined advance was to rely on the tanks’ firepower and a creeping barrage in place of a lengthy preliminary bombardment. The French, who lacked armoured support, were to start their advance 45 minutes later after a short bombardment.

The stage was set for the beginning of the end.

Distribution of forces in front of Amiens, July 1918 (note: Canadian Corps would operate between Australians and French). WO 95/437/1, Fourth Army General Staff war diary, July 1918.

Gives a clear view of the intentions to surprise and overwhelw the enemy forces facing the Allied troops. Also they had to keep these intentions secret from the enemy.This led to the enemy being almost completly having to retreat in disorder.