This is the last in our series of blog posts looking at the Battle of Amiens in 1918. Rather than reflecting solely on its costs – both human and material – or, perhaps less helpfully still, attempting to celebrate a rare victory, it will look at the wider impact of the battle and its meaning for the rest of the war.

German prisoners, 9 August 1918. IWM Q 9193

Without any question, Amiens had been a decisive victory for the Allies. There was no need to rake through the aftermath in search of positive meaning; no need to carefully measure the advance or attempt to compare casualty figures. In a matter of days, a Commonwealth, French and American force had hammered through the German front lines and advanced further than was managed in more than four months of campaigning on the Somme from the summer of 1916. Critically, when resistance stiffened, the battle was shut down and operations were shifted north.

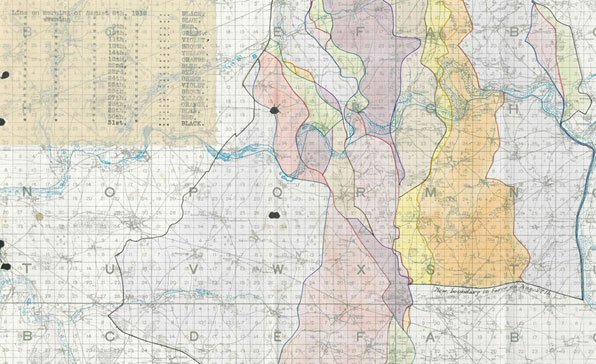

The map below, which featured at the end of the previous blog post, is perhaps the best way to show the scale of success achieved either side of the Somme in August 1918. At least in part, a measure of this success came as a result of the liberal application of technology and battlefield learning.

Extent of advances both sides of the River Somme in August 1918. The enormous gains made by the Australians and Canadians can be seen in the colourless section in the bottom left. Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918. WO 95/437/5.

Comparatively fresh to the fight after halting the German army’s advance at Villers-Bretonneux in April, the Australian Corps had begun to aggressively chip away at German confidence in the aftermath, finessing new ways of fighting alongside tanks and testing the ground over which they would operate in August. Similarly, the effectiveness of the Canadian Corps in offensive operations was so readily recognised by both sides that it had been moved south of the Somme under the greatest of secrecy. Both corps had been spared the bloodletting of 1916 but had honed their fighting skills over a number of engagements the following year.

This says nothing of the capabilities of the rest of the now experienced British and French armies, the RAF nor the overwhelming size and effectiveness of the various branches of the artillery – all of which were probably at their most efficient at this very moment after years of fighting. Nonetheless, victory did not simply come because the Allies had reached the apex of a learning curve.

Just as important to victory at Amiens was the state of the German army – worn down both in strength and morale – and the size of the force facing it. Now somewhat on the back foot and overstretched by its own failed offensive, it was not the army of July 1916 or March 1918. The steady arrival of American manpower and materiel reinforced these problems as much as Foch’s coordinated and concentric blows threatened the German capacity to resist. Critically, while the Battle of Amiens was, without question, a British-led victory when viewed in isolation, it was not fought in isolation. It was instead the first phase of an enormous Allied effort.

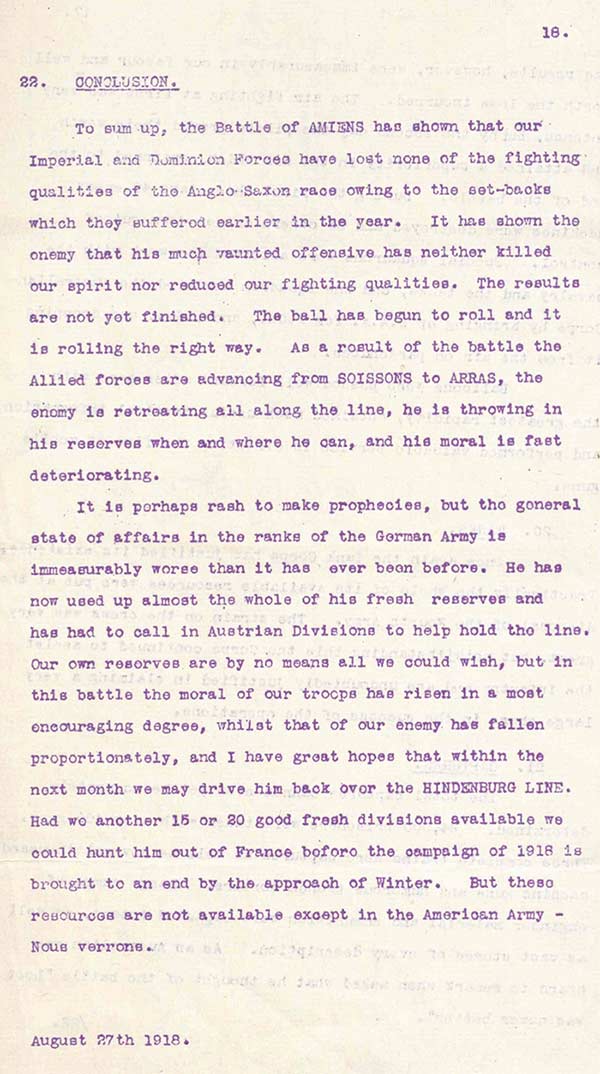

Perhaps one of the pithiest reflections on the battle was that written on 27 August by Lieutenant Colonel R M Luckock, a staff officer with Fourth Army HQ. As he concluded:

The results are not yet finished…[but] the ball has begun to roll and it is rolling the right way.

Although he suggested it was rash to make prophecies, Luckock went on to outline his hopes for the coming months: that they would drive the Germans back over the Hindenburg Line and, should American manpower be forthcoming, perhaps ‘hunt him out of France before the campaign of 1918 is brought to an end by the approach of winter’. In many ways he was not far out in his divinations. Amiens did as much to boost Allied morale and confidence as it did to strip it from the Germans. While it did not end the war on its own, it ushered in a precipitous retreat.

Conclusion from Lieutenant Colonel R M Luckock’s account of the second phase of the Battle of Amiens, 27 August 1918. Fourth Army General Staff war diary, August 1918. WO 95/434/1

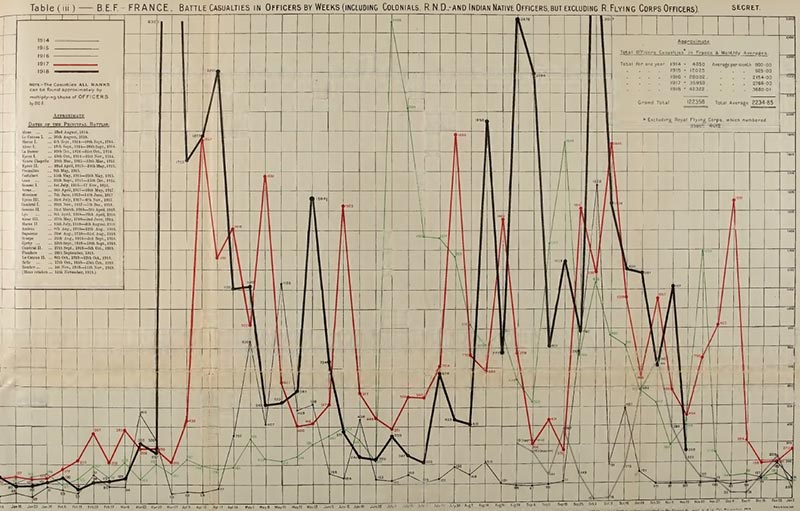

Although fleeting, coverage of the Battle of Amiens and its consequences as part of the centenary commemorations appeared balanced and sensible. It seems to have gained some traction in the public imagination as a forgotten victory, which certainly veers away from the traditional ‘futility’ narratives of the war that have proved so hard to alter. We should not, however, allow one ill-considered narrative to give way to another based on British or Commonwealth triumphalism. Success at Amiens and the Hundred Days offensive that followed came about as a result of a complicated set of circumstances, central to which was Allied collaboration on and off the battlefield. This continuous offensive would prove no less costly than previous attempts to end the war. The difference was, of course, that on this occasion it did.

Graph showing officer casualties in the British Expeditionary Force by month. The thick black line represents 1918. For comparison, the green line is 1916, with the central spike representing the Battle of the Somme. Extracted from Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, HMSO.

My husband’s Grandfather died of wounds and was buried near Amiens 20 May 1918 (at Daours Communal Cemetery Extension) Private George Loveday age 35; G/13336 11th Btn Middlesex Regt. transfer to 114th Coy. Labour Corps (375501).

I would like to know what action he was caught up in in May 1918 – was it near Amiens or Arras and was he was transferred to hospital/Mobile Hospital near Amiens for treatment?

We have visited his grave a couple of times in the past 10 years or so. Sadly my husband died last year, but at least he had been to visit his grandfather’s grave. I would still be interested to know how/why he came to be there – and why the Labour Corps rather than his Regt. (the Middlesex)? Hope you can help me.

Dear Glenda,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email or live chat.

Best of luck with your research.

Kind regards,

Liz.