Extract depicting a coastal town from a contemporary early 16th century artist’s impression, taken from the front cover of the Anglo-French treaty of 1527 relating to ratification of Italian affairs and the privileges of English merchants in France (catalogue reference E 30/1113)

French fishermen casting their nets in the open sea off the Normandy coast on 13 August 1415 would have witnessed a horrifying sight: There was a vast array of ships sailing south across the English Channel for the French coast. The anticipated English military invasion had finally come.

The French port of Harfleur is located on the north bank of the river Seine, very close to the river’s estuary. With a population of approximately 5,000 in 1415, the port was well protected by 4.5 metre thick walls and outworks and with a military garrison of about 200-250 men.

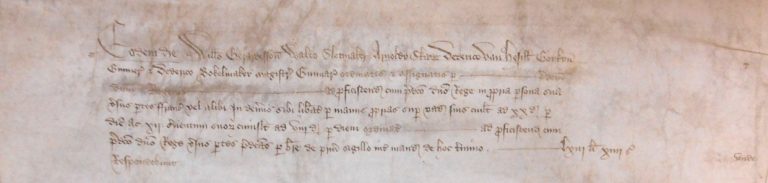

The extracts from the Issue roll accounts detailing expenses paid out of the exchequer to those serving on the 1415 expedition in E 101/45/5 suggest that siege warfare was very much part of the king’s military plans for the expedition. The document reveals that several teams of gunners were attached to the army who would traditionally (though not exclusively) be employed in siege operations to demolish walls and fortifications. Nearly a whole membrane of the roll (membrane nine) is dedicated to wages paid to gunners and master gunners: William Gerardesson, Walter Slotmaker, Arnold Skade, Dederico Van Hesill, Goykyn Gunner and Dederico Bokelmaker were all master gunners paid 20 pence per day. Accompanying them were 12 servants, each paid 8 pence per day.

Entry showing wages paid to William Gerardesson, Walter Slotmaker, Arnold Skade, Dederico Van Hesill, Goykyn Gunner and Dederico Bokelmaker , master gunners (catalogue reference E 101/45/5 m.9)

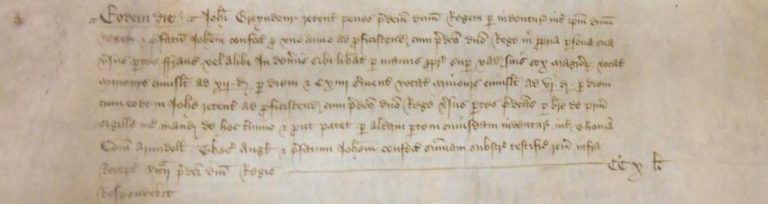

On a separate membrane, wages were recorded for six master miners and 114 assistants under the command of Sir John Greyndour. They would be employed in siege operations to mine under the walls of a town or stronghold. The entry states that each master miner was to receive 12 pence per day and every miner 6 pence per day.

Entry recording wages paid to Sir John Greyndour, 6 master miners and 114 miners (catalogue reference E 101/45/5 m.8d)

The siege: dealing with dysentery and French defences

King Henry V’s army landed near the mouth of the river Seine during late afternoon of 14 August 1415, very close to the port town of Harfleur. Henry is likely to have targeted the town because of its strategic significance as a port on the northern French coast, though this is not certain.

The town was besieged and surrounded on the landward side by Monday 19 August. The siege was to last for just over one month, until 22 September 1415. Although this was not considered a lengthy siege by 15th century standards, it consumed more time and resources than King Henry anticipated.

The resilience of the French defenders, who were emboldened by the late arrival of reinforcements before the town was surrounded, was perhaps underestimated. They went to such length as making frantic repairs to damaged ramparts and defences at night, much to the astonishment and annoyance of their besiegers.

Henry’s army suffered from outbreaks of dysentery known as the ‘Bloody Flux’, probably caused by the pollution of water supplies and even, as chronicler John Streeche suggests, by the bad effects of unripe grapes, other fruit and shellfish! Earls, knights, esquires and archers alike were incapacitated by sickness and many of those affected were granted permission to return by ship to England once the siege had ended. An incomplete list of the men permitted by the king to return home from the port of Harfleur on account of sickness can be found in E 101/45/1. The list was compiled probably as a way of monitoring troops in the field and preventing desertion by able-bodied soldiers feigning illness. This record is on display in the Keeper’s Gallery from October to December 2015.

Perhaps to Henry’s relief, terms of negotiation for surrender were opened on the 18 September. The town finally surrendered to the King four days later on 22 September. It had been subjugated after a hard fought siege at a greater cost to Henry’s army then originally perceived. Although only 37 fatalities were suffered by English forces, including several peers of the realm, the total number of soldiers invalided home due to sickness has been estimated by scholars to be 1,330.

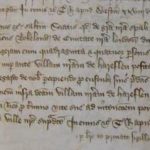

The fate of soldiers serving within an individual retinue (soldiers recruited and serving with a particular captain) has been recorded in annotations written for clerical purposes after the army had returned from France so that wages still to be paid could accurately be calculated. The retinue rolls of Sir Simon Felbrigg in E 101/45/3 and Sir James Haryngton in E 101/47/32 both pictured below reveal the fate of certain soldiers who had died or succumbed to sickness at the siege of Harfleur. The retinue roll for Sir Simon Felbrigg will also be on display in the Keeper’s Gallery.

- Retinue Roll of Sir Simon Felbrigg listing the names of 13 men-at-arms and 36 archers serving in his retinue (catalogue reference E 101/45/3 (2))

- The ‘Sick Roll’ listing soldiers returning to England from Harfleur due to sickness – on display in the Keeper’s Gallery Oct-Dec 2015 (catalogue Reference E 101/45/1)

- Retinue Roll of Sir James Haryngton (catalogue Reference E 101/47/32)

- Entry for archer Thomas Armondernes and annotation stating that he is ‘remaining in Harfleur’ – Retinue Roll of Sir James Haryngton (catalogue reference E 101/47/32)

- Entries for men-at-arms Robert Todenham and Bartimus Appelyarde on the Retinue Roll of Sir Simon Felbrigg (catalogue refernce E 101/45/3 (2))

- Entry recording the grant to Richard Bokelond of ‘The Peacock’ inn in Harfleur (catalogue reference C 76/98 m.6)

Life after the siege

After the port town had capitulated, Harfleur’s French population were expelled from their homes and a substantial force of approximately 1,200 soldiers was assigned to garrison the captured town under the command of the Earl of Dorset.

English officials were also appointed by Henry to Harfleur, recorded in the French rolls in C 76. These documents recorded administrative and diplomatic business concerning foreign kingdoms, but were chiefly concerned with matters and business relating to France.

The rolls record a grant made by King Henry to a certain Richard Bokelond of London, in gratitude for assistance provided to the king at the siege, of an inn in Harfleur known as ‘The Peacock’. This inn no doubt would have been frequented by soldiers from the newly installed garrison, jostling with travellers, traders and settlers who were flocking into England’s newest possession on the continent.

Perhaps among these patrons quaffing ale with his comrades was an archer named Thomas de Amondernes. Thomas was in the retinue of Sir James Haryngton, who had mustered with nine men-at-arms and thirty archers (record in E 101/47/32 – see image above) and is known to have stayed in Harfleur after the English army left the town at the beginning of October 1415. An annotation to the left of his name recorded on the roll states that he ‘remained in Harfleur’. He was most likely part of the English garrison there, through this is not specified. Annotations on this retinue roll were written for the aid of exchequer officials tasked with calculating or re-calculating pay that was still outstanding to soldiers who served on the 1415 expedition.

Thomas was spared what was to be the most challenging phase of the campaign for Henry’s severely depleted army, whose soldiers trudged through the driving autumn rains towards Calais pursued by a French army bent their annihilation. It was on a field near the village of Azincourt (Agincourt) that their fate was to be decided.

Further reading

Anne Curry, Agincourt: A New History (Stroud, 2005)

Anne Curry, The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations (Woodbridge, 2000)

Really well written and interesting!!

Professor Anne Curry’s website http://www.medievalsoldier.org/guidance/agincourt.html

deals in great detail with the muster rolls which goes hand

in hand with her two books – there is also a link where you

can search for a named soldier

very good