Please note: This blog contains ideas, language and imagery from original records which reflect historical viewpoints and attitudes. Some may be considered offensive. However, we think it important to show them here as accurate representations of the record to help us understand the past.

The Central Office of Information (COI) is well known for its public information films. However, it actually employed a huge range of different media to communicate with the public. One important area it focused on was photography and over the years, between 1946 and 2011, it commissioned hundreds of still photographs to be used in the press and publications to serve the aims of different government departments.

After the closure of the COI, its photographs were not collected in one single archive. Since photographs were reproduced and republished in multiple media, copies of them can be found in multiple archives today. They can be found, for example, among records of government departments at The National Archives, but also in collections of COI material held by the Imperial War Museum. The same photographs can also be found printed in COI publications held by the British Library. In light of the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the COI this year, researchers at The National Archives and Imperial War Museums are working together to explore the connections between archival collections.

One of the COI’s largest clients was the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and a key objective was to control how Britain’s actions abroad were seen and understood by the public. Maria Creech has been exploring this area in depth as part of an AHRC-funded collaborative doctoral PhD studentship with Imperial War Museums and the department of Journalism, Media & Culture at Cardiff University. Her research critically examines narratives of colonial counterinsurgency, focusing on photography generated around British and Dutch campaigns in Southeast Asia during the postwar period (1945-60). She is also co-founder of the Network for Developing Photographic Research (NDPR), which provides a platform for PGRs and ECRs working in any area related to photography.

In this blog, Maria outlines how she has traced a single photograph from the Malayan ‘Emergency’ (1948-60) through multiple archival collections, and explains how this can deepen our understanding of the conflict, the COI and its role in government propaganda. The story she tells reveals fascinating insights about how photography can be used as a tool to assert authority and define power relations, particularly in colonial contexts.

The Malayan ‘Emergency’ (1948-60)

In 1948, Britain declared a state of ‘Emergency’ in Malaya, an area in Southeast Asia that was formerly a colonial protectorate and now constitutes Malaysia, Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo. ‘Emergency’ was a strategic term the British used to describe their response to the independence movements that broke out across the Empire during the late 1940s and 1950s.

A region rich in natural resources, Malaya had been one of the most profitable territories in the British Empire. Occupation by the Japanese during the Second World War (1941-45) represented a distinct challenge to British authority in the region, sowing the seeds for an insurgency led by the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), a communist guerrilla army, in the postwar years.

Britain’s propaganda campaign in Malaya

As the British government’s main PR and communications agency, the COI was involved in the management of public information and opinion around the Malayan ‘Emergency’ from the outset. British authorities had initially underestimated both the scale and strength of the insurgency in Malaya, assuming that the independence struggle was led by small disorganised groups of so-called ‘bandits’ and could be quelled in a few short years. By the early 1950s, it was evident to all parties involved that this was not the case.

While the colonial administration sought to discourage civilian support for insurgents ‘on the ground’ with the introduction of harsher governance measures (including curfews, stop-and-searches and forced ‘resettlement’), Whitehall responded with an intensified propaganda campaign that involved more aggressive use of psychological warfare tactics. The COI commissioned photographers to produce images intended for official and press use. Some of these appeared in pamphlets and albums created in collaboration with other government departments, such as the Air Ministry or the Colonial Office.

Tracing this COI-issued photograph across three government archives allows us to construct a clearer picture of Britain’s propaganda campaign and explore how imagery was used to communicate targeted messages about the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya to different readerships.

‘Captured Bandits’

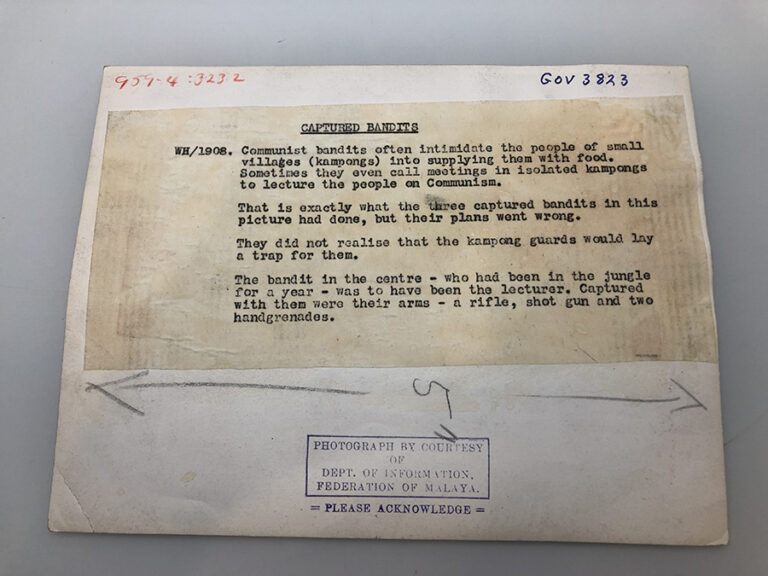

This journey begins in the vast photographic archive of Imperial War Museums, where the original print (GOV 3823) can be located within the COI Post-1945 Official Public Relations collection. It is a typical example of a ‘trophy’ photograph, a practice with well-established ties to military conquest, particularly in colonial warfare settings.

Taken under duress, a photograph of captured soldiers ordered to pose with their weapons could function as a souvenir, as evidence of British military superiority and, upon distribution, as a warning to insurgent armies still at-large. A press release attached to the back-side of the print, titled ‘Captured Bandits’, weaves a dramatic narrative around the individuals in this photograph, whereby they are cast as Cold War villains, who ‘often intimidate the people of small villages (kampongs) into supplying them with food’ and ‘lecture the people on Communism’, and the guards as heroes, who manage to outwit them and ultimately capture them by ‘layi(ng) down a trap’.

Without a stamp identifying the exact production date of this photograph, it is only possible to make an informed guess that it was produced in the late 1940s/early 1950s based on a few clues contained in the official description. The repetition of the pejorative term ‘bandit’ in the press release could imply some connection with ‘Anti-Bandit month’, a widely-publicised recruitment drive led by the British government which aimed to enlist ethnic Malays to the Special Security Forces.

The names of the individuals in this photograph are also absent from any accompanying written record, which isn’t unusual given the genre of this photograph and the tone of the press release, where they are assigned the role of caricatures standing in for a ‘common enemy’.

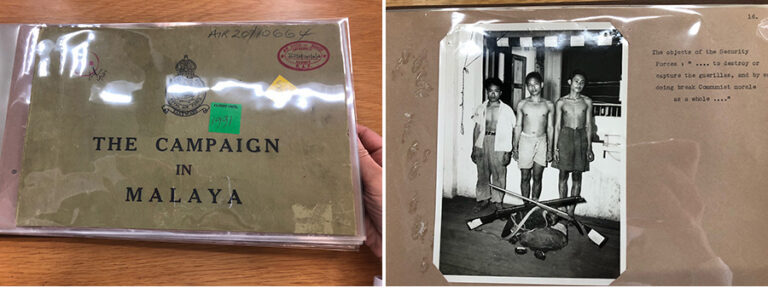

‘Destroy or capture the guerrillas’

The same photograph appeared in an album produced by the Air Ministry in the early 1950s, titled ‘The Campaign in Malaya’ (AIR 20/10664), held by The National Archives. In this publication, there are no references to a backstory involving the laying of traps or lecturing villagers. Instead, the rather brief accompanying text states that one of ‘the objects of the Security Forces’ is ‘… to destroy or capture the guerrillas, and by so doing break Communist morale as a whole…’

As the use of ellipses suggests, this description sits within a broader narrative that evolves as the reader turns each page. In previous pages, photographs documenting the insurgent army’s purported activities aimed at ‘terrorising the population’, including ‘ambushes of trains’, ‘burning motor transport’, ‘sabotaging Estate property’ and ‘slashing rubber trees’, feature as proof of a destructive and tangible enemy threat.

Situating our original photograph within this series helps shed light on the intentions of those involved in its publication. The imagery in this pamphlet is used to illustrate the connection between individual acts of destruction by insurgents and ‘Communist morale as a whole’, placing the local activities of the Far East Royal Air Force – such the ‘capture of guerrillas’ – within the broader context of the international Cold War.

An appeal of this kind sought to make explicit the contribution of the RAF to the broader struggle and, crucially, justify the expense of prolonged combat (an agenda that reveals itself in the final pages of the pamphlet, where the narrative transforms into a plea demanding that British taxpayers fund more sophisticated aircraft).

‘Squatters or Terrorists’?

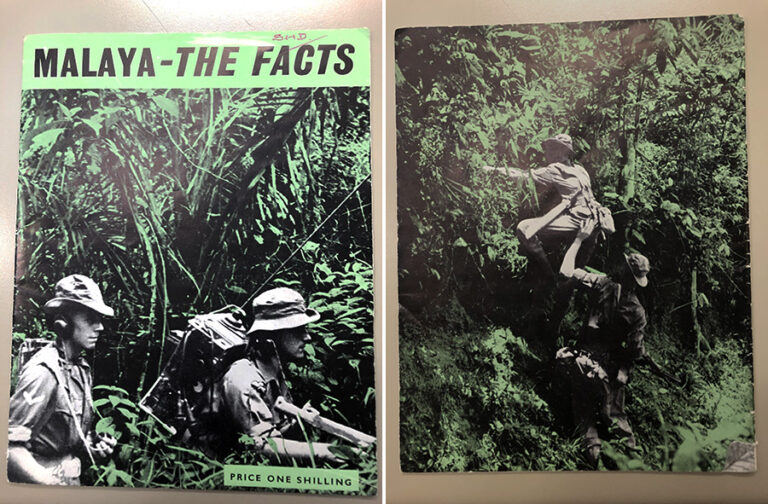

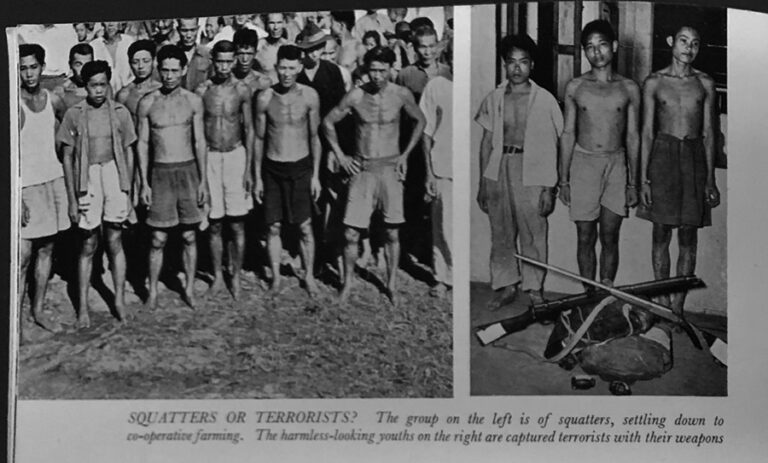

The photograph reappears in a pamphlet titled ‘Malaya: The Facts Behind the Fighting’ prepared by the Colonial Office in London in 1952. This copy belongs to the British Library (PF-192-34). Formulated in order to communicate ‘the facts’ about the Malayan ‘Emergency’ to the British public, information in the pamphlet is arranged in a Q&A format, as if to reconstruct a dialogue between an informed author and an inquisitive reader, and is illustrated with photographs.

The bizarre colourisation of this black and white cover imagery nods to a theme that comes to the surface within this pamphlet: that ‘facts’ are easily manipulated, particularly in irregular warfare contexts, where it matters which side is offering them.

Our original image features alongside another COI-issued photograph accompanied by the provocative caption, ‘SQUATTERS OR TERRORISTS?’ This deeply problematic pairing of images seeks to illustrate similarities in appearance between Malayan-Chinese civilians deemed ‘squatters’ and Malayan-Chinese combatants deemed ‘terrorists’ and spread racial hatred and fear amongst British readers – with the suggestion that even so-called ‘harmless-looking youths’ could be ‘terrorists’ hiding in plain sight.

The violence underlying this comparison is reinforced through dehumanising terminology like ‘squatter’, which implies unlawful habitation of home or land. This was a label the British allocated to Malayan-Chinese and indigenous rural dwellers forcefully displaced into ‘New Village’ resettlement camps in the 1950s as part of a plan devised by General Sir Harold Briggs[ref]Teng Phee, T. Behind Barbed Wire: Chinese New Villages during the Malayan Emergency, 1948-1960, (Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2020).[/ref].

By 1952, the British government had abandoned the term ‘bandit’ in favour of the term ‘terrorist’, amidst criticism at home and abroad that ‘banditry’ misrepresented the level of organisation and sophistication of insurgent forces in Malaya[ref] Carruthers, S L Winning Hearts and Minds: British Governments, the Media and Colonial Counter-Insurgency 1944-60, (Leicester University Press, 1995).[/ref]. ‘Terrorist’, of course, is also a loaded term with a complex usage within colonial and neo-colonial counterinsurgency warfare settings, where it is often levelled by those in power in order to delegitimise individuals resisting oppressive rule.

From ‘captured bandits’ to ‘terrorists’

By tracing the same photograph through different government-issued publications, we can begin to make sense of how a single image can speak to multiple agendas and audiences. The journey from ‘captured bandits’ to ‘guerrillas’ to ‘terrorists’ actually tells us very little about the individuals depicted in this photograph, but it does speak volumes to the sense among British officials that the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya was rapidly spiralling out of their control.

While much about the actual fighting was out of their hands, this material shows how photography could be adapted, annotated and circulated in emotive ways that appealed to public opinion, seeking the justify an undeclared war in Malaya and instil a diminishing Empire with a sense of its own importance.

If you have any questions or comments about this research, please feel free to contact Maria Creech on Twitter at @MariaCreech10.

To find out more about The Central Office of Information and the 75th anniversary collaboration between The National Archives, Imperial War Museums and the British Film Institute, please see our introductory blog and follow our hashtag #COI75 on Twitter.

An interesting and very informative.

I recall the COI as the producer of the glossy brochures, and associated recruitment material for the armed forces as well as the familiar public information films.

Although outside the scope of this post, did COI produce similar material for other conflicts, such as the Troubles in Northern Ireland – where the term ‘Bandit Country was used to describe areas of South Armagh where the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and its vari splinter groups (such as the Provisional IRA -PIRA) operated, at times to devastating effect?

The excellent book “War of the Running Dogs” by Noel Barber gives a greater sense of clarity to the issue. Referring to Communist Terrorists (CTs) throughout, Barber illustrates how the insurgency by Chin Peng’s Malayan Communist laid the basis of ethnic strife as the majority Chinese communists, with support from the fledgling PRC sought to destabilize the transition of power from the United Kingdom’s colonial administration to a multi-ethnic Malaya.

Whilst the term squatter might be seen as offensive, it is quite accurate in terms of the land on which they lived and the New Villages, or Kampung Baru (in stark contrast to the Strategic Hamlets in Vietnam) were very successful at preventing supplies reaching the CTs. It’s also very important to note that the insurgency continued in one form or another until the 1980s, and that it threatened first independent Malaya after Merdeka, and then Malaysia.

Finally the barbarity of the CTs was fairly typical of other communist movements and insurgencies in the cold war, and must be seen in that context, not purely that of the fighting for independence, an independence the British were in fact more than willing to grant to Malaya.

The most interesting article fails to point out that the Malayan Emergency was part of the wider Western fight against Communism, or that the indigenous Malays generally sided with, and supported, the British forces.

Just happened to see this week an interesting photo from the Malayan Emergency namely a photograph said to be of training of Ferret Force by Quartermaster Sergeant Robertson. The blurb on the back of the photos makes the point that most of Malaya’s 500 insurgents are Chinese. https://imsvintagephotos.com/products/quartermaster-sergeant-robertson-in-a-demonstration-to-men-of-ferret-force-shows-them-unarmed-combat-vintage-photograph-525186?_pos=9&_sid=50cfd3f78&_ss=r

Does the author of this blog post work for the British National Archives or the Chinese Communist Party?

Very interesting.

Somewhere in the family achieves is a photo of a very, very young me with the crane that was damaged (blown up?) by the bandits/terrorists/insurgents at the coal mine at Batu Aurang, outside KL, in 1947/8? (My dad was the mine accountant)

This was real war, and I understand I used to have my hair cut by the local garrison barber.

And my parents both carried guns when they were off the mine estate.

They say the first casualty of war is truth.

As a boy of 10 years to 14 years, between early 1956 and late 1960, I lived in Singapore. When we first arrived in the then Crown Colony of Singapore, the Malay Peninsula was virtually “out of bounds” as Johore State was a hotbed of the Independence insurgency. However, by 1959 there were various grades of “dangerous areas” and we, as a family, holidayed in Malaya. I remember that driving north through Johore one had to keep up a minimum speed with no stopping. We usually stayed overnight in Malacca, a very pleasant town in the late 1950s, before driving north once again to Port Dickson and Kuala Lumpur. Although we were on a family holiday, I remember the tensions as we drove through what were known in those days as “Red” areas (Johore) and the lessening of that tension in the “White” areas as we entered the States of Malacca and Negri Sembilan. Even as a boy of 11 – 13 years of age it was apparent to me that there was an underlying racial prejudice to the British propaganda, which I found disturbing as two of my boyhood chums were Singapore Chinese. I remember feeling extremely uncomfortable with some of the newspaper reports in the Straits Times. Generally speaking the guerrilla insurgents in most colonial independence movements turned towards the Communists, because the Western democracies were hostile to them and to their aims. We were in Singapore when Independence was granted and when Singapore became self-governing – interestingly, once they had their own representative governments neither of these colonial possessions turned to Communism. Following the disasters of the Second World War defeats of British forces in Malaya and the catastrophic surrender at Singapore post-war Independence was inevitable (as a boy I used to explore some of the abandoned 15-inch gun emplacements of the old Faber Fire Command and the Buona Vista Battery).

My father had worked for the COI in England and was sent to Malaya by the Crown Office in 1953 to work on what was deemed ‘psychological warfare’. In the latter part of his (and our as a family) sojourn there, they developed ideas of cascading leaflets into the jungle from planes, suggesting that it was easier for the CTs to surrender and come out of the jungle, than to remain and continue fighting. To a large extent, he was successful. I agree with earlier comments that the CTs were almost entirely Chinese, many of whom had remained fighting the British after World War II. The idea of resettlement in kampongs, although restrictive for the villagers, did solve the problem of the CTs receiving food.

Whilst acknowledging the work done by Maria Creech, it has to be remembered that the CTs had killed many rubber plantation managers and their families and ambushed and killed the Governor in about 1949. My father was also working towards the independence of Malaya, which was always Britain’s goal.

When I was a young child, the neighbouring family returned from a posting to a rubber plantation Malaya during the ‘Emergency’. My parents were invited for an evening meal. My mother came back seething with anger. ‘The natives there don’t make good servants,’ was the comment that she remembered for years after. It is a shame that none those commenting on this blog so far were among the ‘natives’ condemned by that neighbour who, probably, like Diana Bickerton, pretended in later years that ‘the independence of Malaya was always Britain’s goal’. This bizarre inversion of the reality provokes the simple question of why, if independence was always a British objective, it was taken away in the first place, a decision then maintained by open use of force for many a decade.

One does not have to be a protagonist for the MNLA or the Communist Party in Malaya to recognise that the origins of the uprising they sought to lead are rather more than that given by a reference to the Cold War in the blog.

The statement that ‘Occupation by the Japanese during the Second World War (1941-45) represented a distinct challenge to British authority in the region’ is more than a bit odd given that the crushing defeat inflicted by the Japanese in 1941 was above and beyond ‘a distinct challenge’.

The Communist-led guerrillas who operated against the Japanese occupation in the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army were treated as an ally by the British. They were provided with some training and with supplies of weapons. They also, like so many others in the colonies of European nations that were occupied by the Japanese, looked forward to independence after the war rather than recolonisation by the British, the French or the Dutch. It was British troops that arrived in Java, Saigon and Singapore as quickly as possible after the Japanese surrender, and, in the case of Vietnam, after Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of independence in Hanoi on 2 September. Neither the French nor the Dutch were prepared to grant independence and the result was a slow but inexorable drift to war.

Malaya was a bit different. The new Labour government played a double game. On the one hand, members of the MPAJA were welcomed to victory parades in London, on the other, the British authorities set about recuperating all the weapons they could from MPAJA stores that had either been air-dropped by the British or captured from the Japanese. In at least one instance known to me, copies of the maps prepared by British military intelligence to guide British troops seeking to capture these weapons and pinpointing particular dumps, were passed to MPAJA contacts so the weapons could be moved to new hiding places. May be there is evidence on this in the archives.

The British authorities did not open up a democratic route forward for the people of Malaya in 1945 and 1946, control of the country’s rubber production was considered too important for that. As the conflict over the future of the country and the rights of its different peoples developed, the British authorities were fully conscious of the way the ethnic differences in the country (to express it crudely, Chinese labourers in the plantations, Malays in agriculture and the towns, the descendants of indentured Indian labourers in the mines and some plantations, other groups in the forests) could be played upon to isolate and eventually defeat the MNLA.

It would of interest to know what there is in the archives of the COI when it comes to the disclosures of the display of severed heads of MNLA members by British soldiers, how that was discussed behind the scenes and what images might have been considered suitable to counter the impact of the photos of those heads on British public opinion.

From some of these comments it appears that the COI did an excellent propaganda job! Pity the coverage of the research excluded, as always, the Borneo confrontation and insurgency – there are many fascinating parallels with the Malayan Emergency such as the COI role in propagating the ‘hearts and minds’ myth.

Dear Chris Myant,

In reference to your comment, ‘It would of interest to know what there is in the archives of the COI when it comes to the disclosures of the display of severed heads of MNLA members by British soldiers, how that was discussed behind the scenes and what images might have been considered suitable to counter the impact of the photos of those heads on British public opinion.’

I was born in British Malaya at the time of the emergency. My mother was Chinese, and my father was a British soldier. He is now deceased, but from 1954 until 1961, he was stationed in Malaya. He was actively involved in fighting CTs. He told me that when they were first in the jungle fighting ‘communist terrorists’, they used to cut the heads and hands off all the terrorists that had been killed. They would then take the heads and hands back to camp, where they would be laid out and photographed by Special Branch or the army equivalent, and the fingers would also be finger-printed. This allowed the authorities to build up a comprehensive intelligence picture of the insurgents and their close and wider families.

My father also said that after they had finished their ‘jungle patrols’ they would load up their Dayak guides with the heads, hands, and, interestingly, parachutes just before they entered camp. The Dayaks were paid bonus money ‘for them’. However, if my father or one of his colleagues had brought a head in, they, unlike the Dayaks, would have gotten nothing for their effort. Once paid, the Dayaks would share the beer money between themselves, my dad, and his colleagues. Apparently, according to my father, this ended when his and other sections were issued cameras.