Following the success of our ‘Behind the Scenes’ repository tours we are currently running tours based on specific themes: this month’s was ‘Authors in the Archives’. Here are a few of the original documents we selected to show to the tour group…

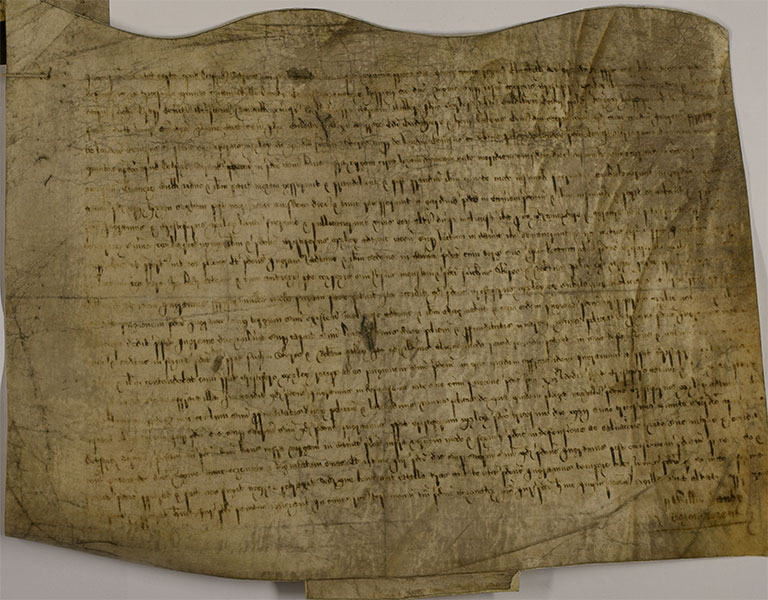

A Tudor tragedy

In 1925 scholar Leslie Hotson first identified this document as relating to the death of poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe at the age of 29.

This copy of the inquisition into the death of ‘Christopher Morley’ on 30 May 1593 states that the dead man had quarreled with his companion Ingram Frysar over the bill in a Deptford tavern. ‘Morley’ was said to have attacked Frysar with a dagger; in the scuffle Frysar got hold of the knife and

‘gave the said Christopher there and then a mortal wound over the right eye of the depth of two inches and the width of one inch’.

Marlowe was killed instantly; however, the inquest ruled that Frysar had acted in self-defence and he was later released.

The successful young author of ‘Doctor Faustus’ is widely believed to have been involved in the espionage network led by Sir Francis Walsingham, spymaster to Elizabeth I, with evidence suggesting he may have been recruited while still a student at Cambridge. His involvement in the shadowy world of Tudor espionage has led to much debate as to the circumstances of his death and whether it was, indeed, simply the result of a moment of drunken violence.

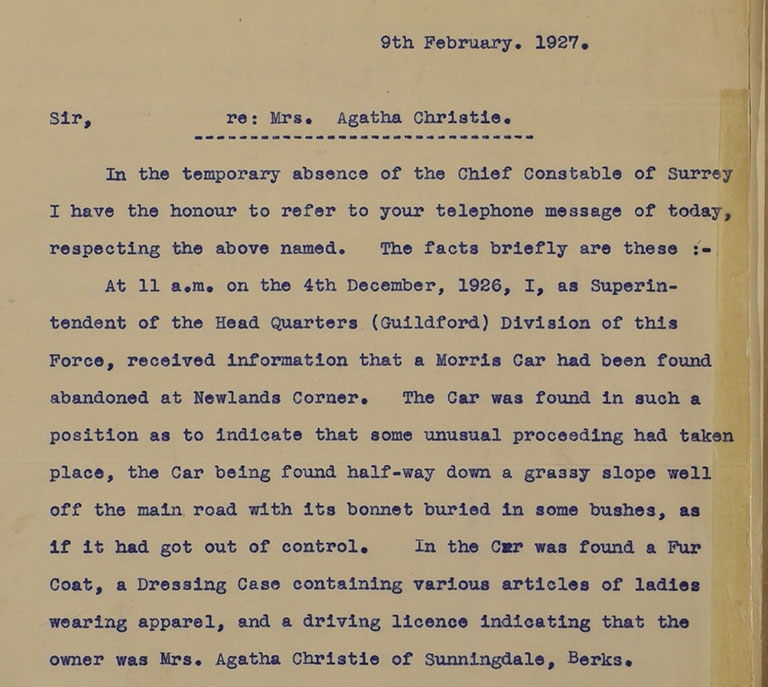

The Christie mystery

Late in the evening of 3 December 1926, Agatha Christie left her home unexpectedly and disappeared into the night. The following morning her car was found abandoned on a grass verge with the engine running, but there was no trace of her, sparking a major search by both police and public volunteers. Theories abounded, with many believing the author had met with foul play or taken her own life.

Eleven days after her disappearance, Christie was recognised staying in a Harrogate hotel under an assumed name, and claiming to remember nothing of what had occurred to her during the interim. Curiously, the name she had chosen to use at the hotel was that of her husband’s mistress: this led many to believe the whole incident was a stunt designed to punish his infidelity.

Other widely-held theories are that an injury sustained by the crashing of her car caused temporary amnesia, or that she was suffering from a depressive ‘fugue’ state which caused her to forget who she was. The cost to the Berkshire police who conducted the search was put at £25, an amount which Christie’s husband refused to reimburse.

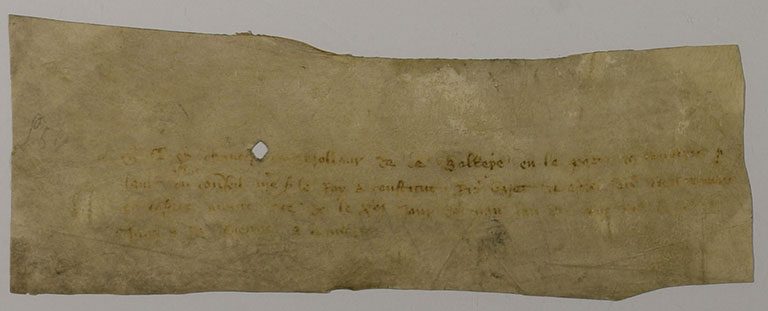

The Comptroller’s Tale

Although we know him principally for his poetry, Geoffrey Chaucer served as a prominent public servant throughout the reigns of Edward III, Richard II and Henry IV. In 1374 Chaucer was appointed Comptroller of the Customs of Wool, Skins and Tanned Hides for London. His long and varied career included several diplomatic missions overseas, which may explain the need for this document, dating from 1378, appointing a deputy to cover for him in his absence.

By this date he had been producing popular poetical works for many years, but was yet to start work on ‘The Canterbury Tales’, which was begun in 1387 and remained unfinished on his death in 1400.

It is possible that this document was written by Chaucer himself, as a condition of his role as Comptroller apparently stipulated that he write the accounts in his own hand. Although it is only a small piece of parchment with a few lines of extremely faded administrative French, the possibility that it could be penned in Chaucer’s own handwriting makes this document feel like a tiny treasure.

Find out more about Chaucer in the archives.

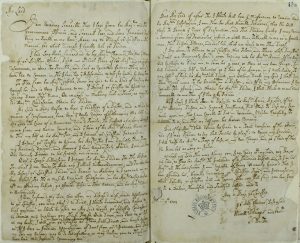

The pilloried pamphleteer

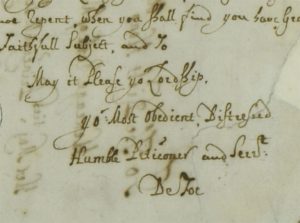

Daniel Defoe, author of ‘Robinson Crusoe’, was a prolific writer of political pamphlets and satires, one of which landed him in serious trouble in 1702. He was arrested and tried for dissent. While awaiting trial he wrote this letter to the Secretary of State, begging for the Queen’s mercy and for his punishment to be ‘a Little More Tollerable to me as a Gentleman, Than Prisons, Pillorys, and such like, which are Worse to me Than Death.’

- Letter from Daniel Defoe to the Secretary of State begging for clemency (catalogue reference; SP 34/2/27)

- Signature of Daniel Defoe (catalogue reference; SP 34/2/27)

Despite this plea, he was sentenced to three months in Newgate Prison and had to endure three humiliating sessions in the public pillory. Although traditionally this gave the public a chance to bombard the prisoner with any disgusting materials they had to hand, it is said (probably falsely) that Defoe’s audience instead threw only flowers. His experiences of trial and imprisonment heavily influenced his later work ‘Moll Flanders’, whose Newgate-born heroine experiences the full horror of imprisonment within its walls during her lively tale.

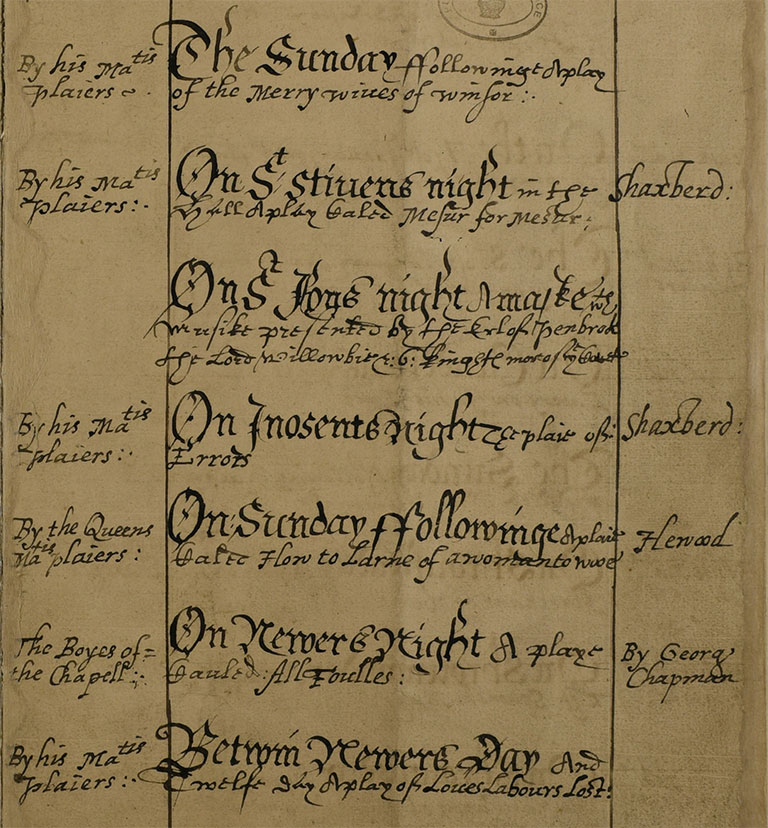

Shaxperd in the Revels

This is the account of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels at the court of James I for the period November 1604 to October 1605.

Entries for performances of Shakespeare in the account book of Edmund Tylney (Document reference; AO 3/908/13)

It lists the dates that entertainments took place, along with the titles and authors of the plays; it features several performances of ‘Shaxberd’ plays, performed by His Majesties Players.

This document was believed to be a forgery until its authenticity was proved in the 1930s,; it is one of 90 documents relating to the life of Shakespeare that were collectively granted UNESCO world heritage status in early 2018 – see here for more details.

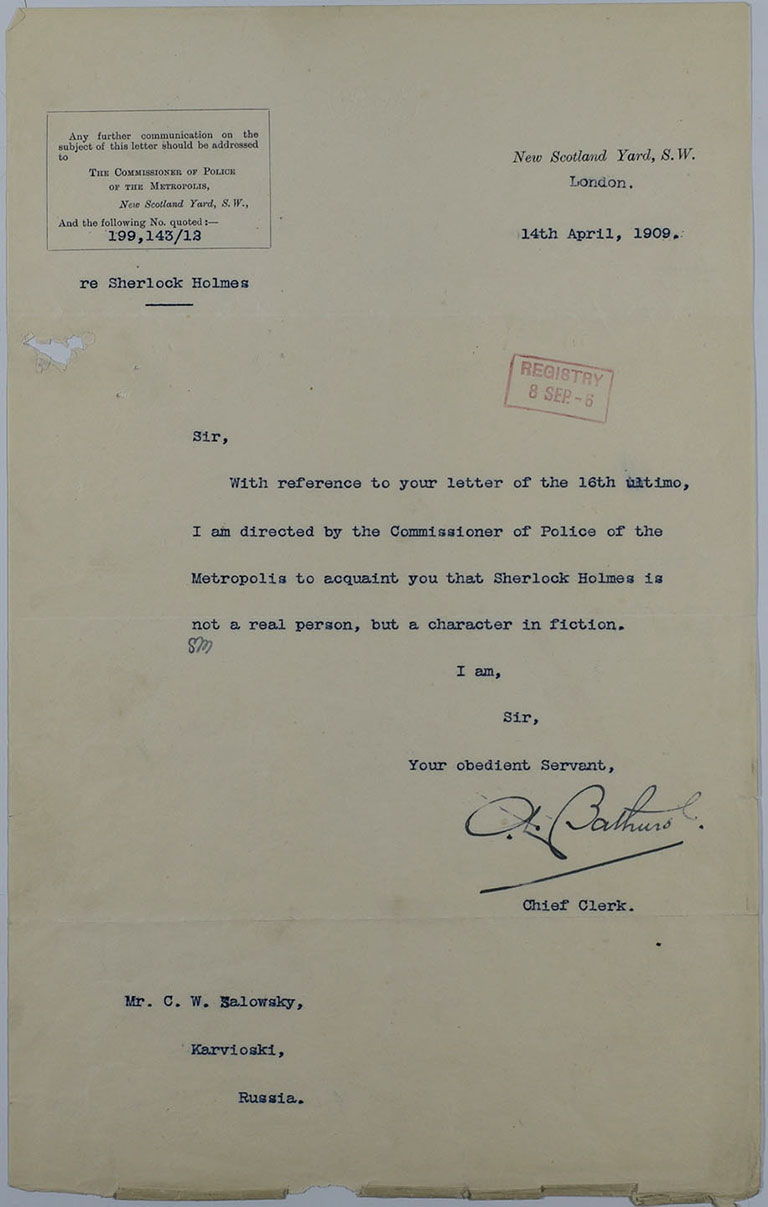

Fans of the fictional detective

This file contains numerous letters written to Scotland Yard from individuals hoping to make contact with fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. Enquiries come from all over Europe including Naples, Moscow, Romania and Vienna. Each was answered with a letter explaining that Holmes was a purely fictional character and would therefore not be able to assist.

Letter explaining that Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character and not a working detective (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/8449)

At the time the stories were written, Holmes’ fictional address – 221b Baker Street – did not exist; however, a reallocation of the street numbers in the 1930s meant that it became a real address, and letters to the detective began to arrive there instead of being forwarded to Scotland Yard. The Abbey National branch which occupied the address employed a secretary to answer these letters, explaining that Mr Holmes was no longer detecting and had left London to enjoy a rural retirement in Sussex.

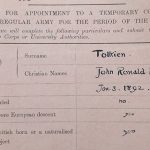

The battles of men

This is the First World War service record for John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, who joined the Officer Training Corps in 1914 and was commissioned the following year. After training, he was transferred to the 11th (Service) Battalion with the British Expeditionary Force and his active service began.

Soon afterwards he was transferred to France where his battalion was sent to the Somme.

- Excerpt from Tolkien’s record (catalogue reference; WO 339/34423)

- Letter from Tolkien to the War Office declaring himself ready for further duty (catalogue reference; WO 339/34423)

In October 1916, Tolkien contracted trench fever and was sent back to England to recuperate, eventually being deemed medically unfit to return to active service despite declaring himself willing.

In 1925 he was appointed a Fellow at Pembroke College, Oxford where he began work on ‘The Hobbit’ as well as early drafts of a story that was later to become ‘The Lord of the Rings’. The loss of close friends during the war had affected him deeply, and the themes of battle, endurance and, above all, fellowship lie at the core of his most famous works.

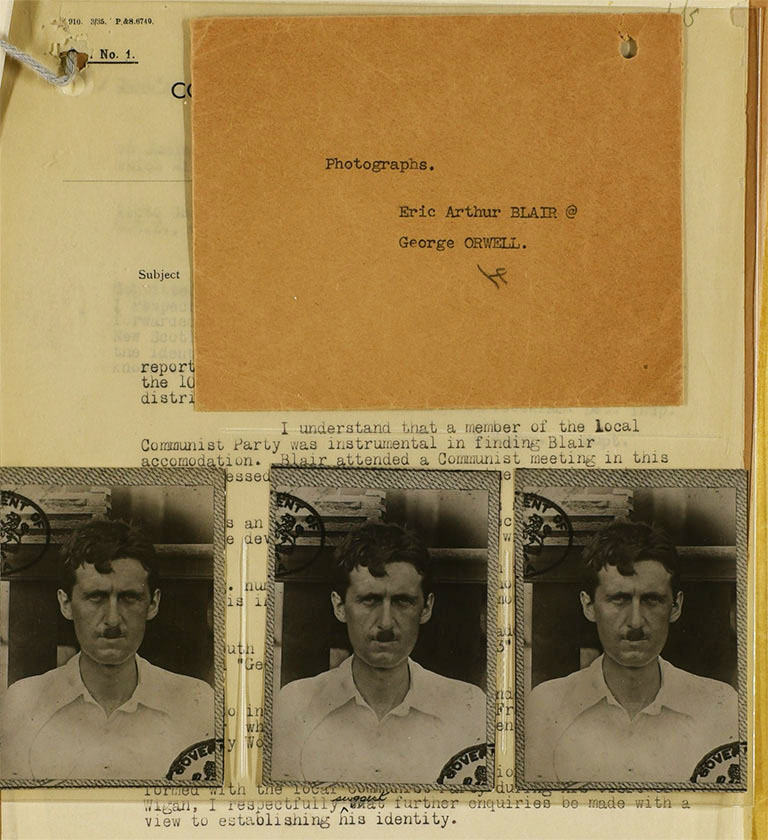

Special Branch is watching you

Ironically, the author of ‘1984’ – perhaps the ultimate novel of State surveillance – was unaware that he was monitored by Special Branch for nearly 15 years as a suspected Communist. Suspicions seem to have been based on his reading of and contributing to left-wing papers, his abrupt resignation from the Police Service in India and his relationships with left-wing and ‘suspicious’ persons. The surveillance ultimately came to nothing, with MI5 disputing Special Branch’s findings and describing Orwell as having ‘strong left wing views but… a long way from orthodox Communism’.

Photographs of Eric Blair/George Orwell from the Special Branch file (catalogue reference; MEPO 38/69)

Art or filth?

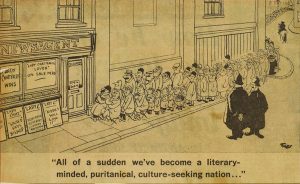

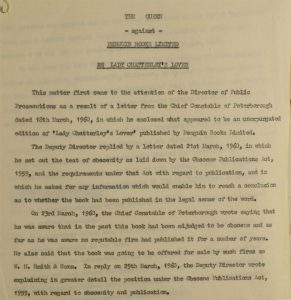

- Cartoon depicting the public interest aroused by the trial (catalogue reference; DPP 2/3077)

- Excerpt from the summary of the case (catalogue reference; DPP 2/3077)

Although a heavily-edited version of D H Lawrence’s novel ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ was published in England in 1932, it was not released in its complete form for a further 28 years. When the full, uncensored edition was released by Penguin Books in 1960, they were swiftly prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act 1959 which had just come into force.

The trial was avidly reported in the media, leading to a renewed interest in the book and triggering much debate on literature, sexuality and the social code. To escape prosecution the publishers had to prove the work had literary merit and so produced several authors, academics and other respected literary personages to testify that this was the case with Lawrence’s book.

Penguin were ultimately found not guilty and the trial marked a pivotal moment in the loosening of moral strictures and emergence of a more relaxed attitude to what had previously deemed as too obscene for public consumption.

Try one of our Behind the Scenes tours

Visit Eventbrite for information on our regular ‘Behind the Scenes’ and themed tours, or contact us to arrange a private group tour:

- dsdtour@nationalarchives.gov.uk

- 020 8876 3444 ext 2132