We’re often faced with the challenge of bringing the stories behind our records to life. In recent times, we’ve hit upon a powerful approach: making audio plays, in collaboration with the team at Applied Stories.

In this short series of blogs we’ll share experiences from the development of Being and Not Being, two multilingual audio dramas in English, Swahili and Hindustani, based on records of African and South Asian troops from the Second World War. Together we’ll explore the records that inspired this new project and the writers’ experiences of working on it.

But why have we chosen to work with audio? How did this begin, and what makes the medium so special? In this first blog we hear from Fin Kennedy, Artistic Director of Applied Stories, and Mel Pennant, who has written three plays for The National Archives (more than anyone else!).

Fin Kennedy, Artistic Director

What have you worked on with The National Archives?

Fin: The National Archives has commissioned a large amount of audio drama over the past eight years. They’re actually the biggest commissioner of audio drama after the BBC. I recently put all the audio plays I’ve worked on for The National Archives into a SoundCloud playlist and there are 24 of them, totalling over five hours of drama!

All of The National Archives’ plays feature untold and unknown true stories from this nation’s history, all of them inspired by real records, and many of them about the experience of the UK’s many diasporas from former British colonial territories. These dramas now comprise a unique body of work.

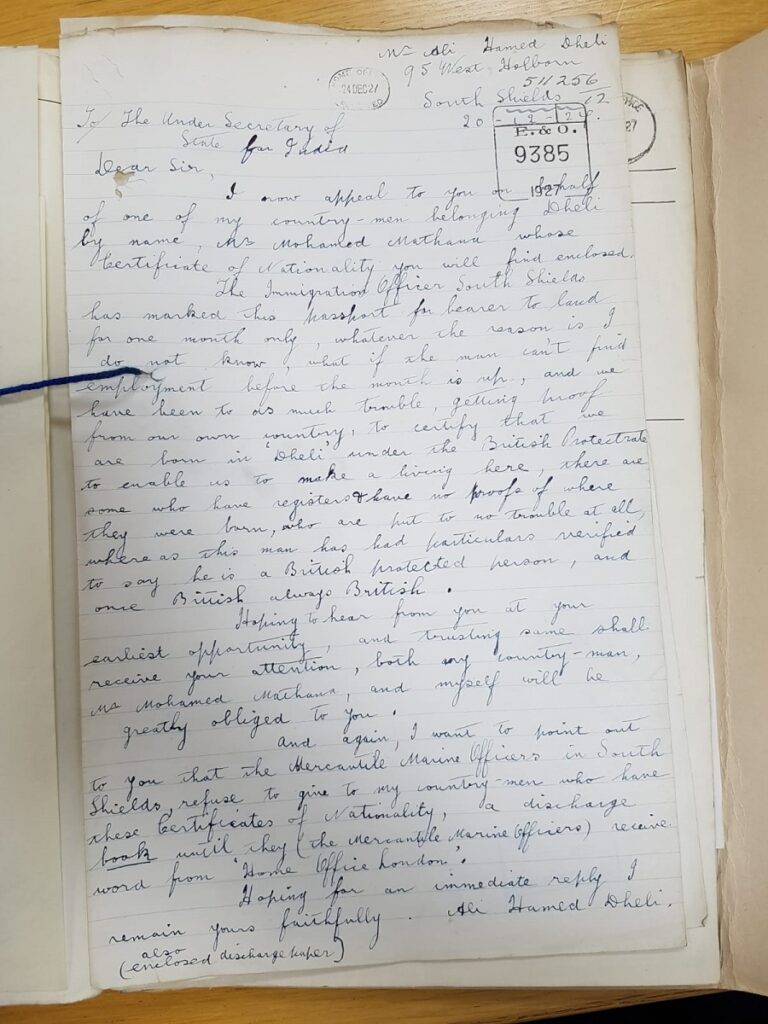

We go from the trenches of WW1 and the Indian independence movement, to Liverpool and South Shields in the 1920s following some South Asian merchant seamen tangling with British bureaucracy, then we’re in Dublin in 1921 for a double bill about the role of propaganda in the brutal Irish war of Independence.

Then it’s on to a photographic portrait studio in Butetown, Cardiff in the early twentieth century for some imagined stories of long lost families, where all we have is their picture… That example is From May to Etta with Love, the first regional project for The National Archives and Applied Stories, a collaboration with Glamorgan Archives in Cardiff.

How did you start working with us?

Fin: I used to run a touring theatre company called Tamasha, and Iqbal was not long in his role. We didn’t know each other, but he just wrote in one day about the potential for a drama collaboration to bring archives to life.

I saw a chance for a unique collaboration and got straight on a train to Kew. As soon as I stepped foot in the building, what I call my ‘spidey sense’ went off. As a writer myself I could just feel that this place was teeming with stories! What started as a theatre collaboration quickly evolved into audio, when we were looking for a way for the plays to live on.

Listen to a play Mel wrote for The National Archives on YouTube

Why do you think audio is so good for bringing archives and history to life?

Fin: Audio drama is perfectly suited to time travel. You can literally go anywhere and do anything, and it all costs the same. It’s just sound effects. But sound – or rather hearing – is an under-rated sense, and perhaps the most powerful in its emotional impact.

That’s especially true of non-broadcast drama, because everyone is listening through headphones. That turns audio drama into movies for the mind. It’s also a fast track to empathy; proximity to the characters has a powerful emotional effect.

We’re able to drop in on crucial historical moments, and bring them roaring to life with personal stories, with great writing and glorious sound design – and all on a fraction of the budget of TV or film. It’s this closeness to the listener, like being inside their head, which amplifies audio drama’s power to shock, move and create empathy.

More practically, pre-recorded audio is great value for money, because the plays live on. After a live launch, each play has an indefinite afterlife on demand, can be played in talks and workshops around the country, and on The National Archives website, where listeners can also see copies of the original documents and learn more about the history.

Mel Pennant, writer

How is writing for audio different to writing for the stage or TV?

Mel: I asked my daughter what she thought the power of these plays was, and she’s eleven. And she said, ‘Mummy, it’s the words. They mean so much more.’

And I thought, she’s really right about that, isn’t she? Because I guess with an audio play, you just have to work that much harder. You have the words themselves, the sound, the silences, but they have to do so much more than, say, TV or something. That’s a visual medium.

You can’t be lazy, I don’t think, when you’re listening to a play. It’s a real collaborative process between the writer and the listener in a way that maybe you don’t get with other mediums. You have to work quite hard to engage the audience but once you’ve got them, they have to work quite hard with you to kind of realise the story and the picture. And I think potentially that enables you to achieve something which is quite profound.

You can get really, really personal in audio in a way that is, again, quite different from other mediums. It makes the big very small. So, you know, we’ve got world wars, we’ve got Windrush – these huge, huge things – and audio enables you to just bring it down to the person.

A big thank you to Fin and Mel for sharing their thoughts. Look out for further blogs about the Being and Not Being audio project, including how our collections have inspired the writing process. And when we announce the audio dramas’ release!