Louise Bell is currently undertaking an AHRC funded Collaborative Doctoral Partnership with The National Archives and the University of Leeds exploring British state provision of prosthetic limbs in the two world wars. Her research explores the social, economic and cultural impact of war amputations, with a focus on the agency of disabled individuals as demonstrated through interactions with political and industrial institutions.

Her blog below focuses on the different materials used for manufacturing artificial limbs. Using blueprints found within records created by the Munitions Invention Department, Louise shows the involvement of the government in the push for standardisation and design innovation of artificial limbs following the First World War.

– Laura Robson-Mainwaring, Principal Records Specialist, The National Archives

The First World War made the need for a strong artificial limbs industry in Britain very apparent. That is not to say that such an industry did not already exist here – accidents and injuries, in the workplace in particular, meant that a well-developed market for artificial limbs had already been established. However, the First World War brought with it a larger concentration of men, in a relatively short period of time, who returned to Britain requiring the aid of this industry.

Around 41,000 men returned from the First World War missing one or more limbs (noted in PIN 38/304). Limb fitting centres were set up around Britain specifically to provide support and aid for these injured ex-servicemen. As the name suggests, the main role of these institutions was to fit men with their new artificial limbs and to make sure that they could use them properly. A lot of work has been done exploring the rehabilitation of disabled ex-servicemen, so in this blog I’ve chosen to look at the artificial limbs themselves.

Wooden limbs

Artificial-limb-makers were housed on-site at the limb-fitting centres, with a large variety of companies being involved in the production process. The limb-fitting centre at Roehampton brought in manufacturers from across Britain, as well as from America. However, the centre at Erskine, Scotland, used the skills of local shipbuilders to help with manufacturing the artificial limbs for their hospital.

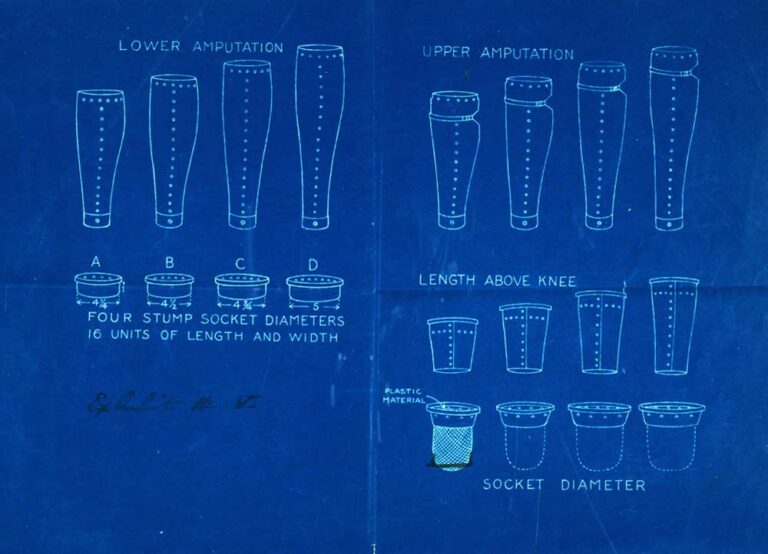

The one thing that these manufacturers all had in common were that they primarily worked with wood. For the majority of the First World War, this was the material that most artificial limbs were constructed from. Lighter, more pliable wood such as willow was the preferred material of choice. This allowed for the sockets (the section which attached to the body) to be more adjustable. Naturally, each man and each injury was different – artificial limbs couldn’t be one-size-fits-all.

The above blueprint highlights this perfectly and demonstrates just how small some of the differences in size could be. These differences might be small, but they made all the difference when it came to an ex-serviceman being comfortable when using his artificial limb and being able to use it well. An ill-fitting limb could cause all number of problems.

Experimentation with materials

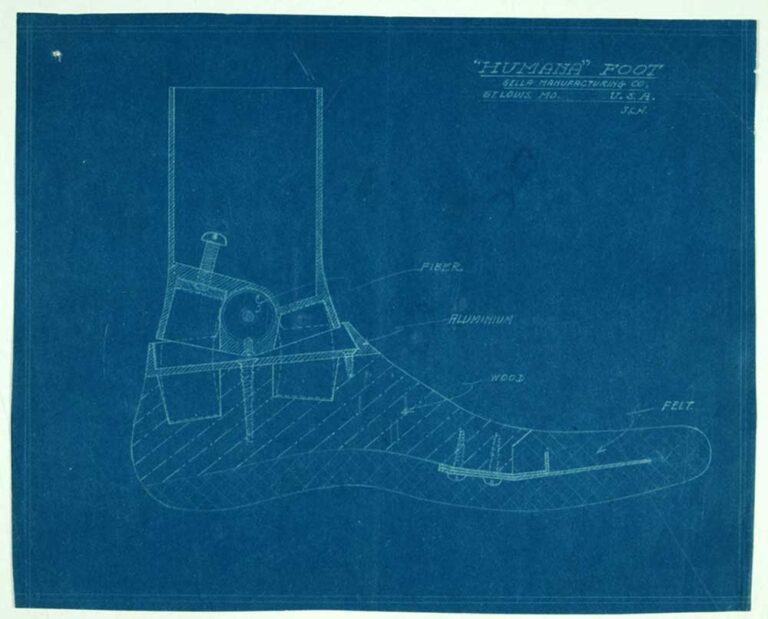

Towards the end of the First World War and into the interwar period, we start to see artificial limbs being constructed from different materials and more experimentation happening with these materials. Light metal in particular began to replace limbs made of wood. The metals chosen were lighter, stronger, and more durable than wood. Ex-servicemen started to prefer these more ‘modern’ limbs, especially with the added bonus that they did not need to be repaired as soon or often as some wooden limbs did.

Repairs could be a lengthy and time-consuming process, meaning that the ex-serviceman had to spend more time in the hospital, or had to send his artificial limb away for the repairs to be undertaken. By the end of the war, it was policy that men would be given duplicate limbs to try and alleviate some of this inconvenience. The government also tried to implement standardisation of limb parts to make the process that bit easier, especially if a manufacturer was having to repair a limb that wasn’t his own.

The idea of standardisation worried a lot of ex-servicemen as they thought that they were going to be given ill-fitting limbs from then on, and they weren’t happy about this. However, as mentioned earlier, each limb was personal to the man, so they still had to go through the proper fitting process. Having standardised parts ultimately made the manufacturing and repairing processes a bit quicker.

Adaptation for work

It wasn’t just the manufacturing of artificial limbs that was important, however. One of the main purposes behind offering veterans artificial limbs was to allow them to re-join the world of work.

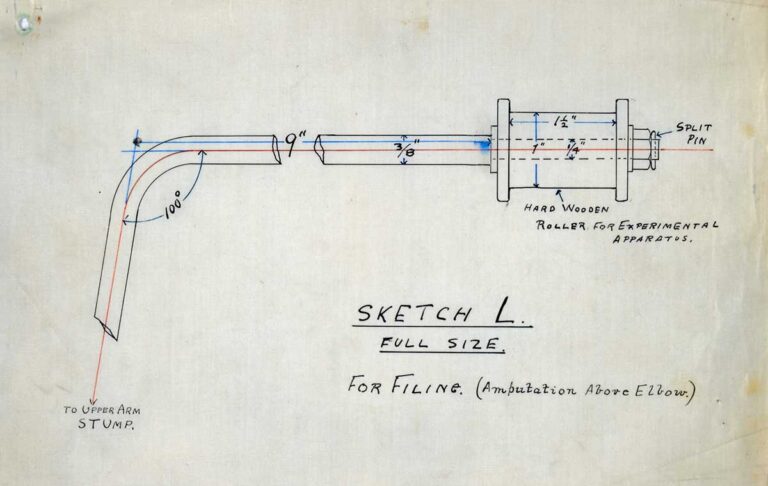

For artificial arms in particular, attachments could be provided. These ranged from everyday household tools to specific tools needed for the jobs they were now undertaking.

Observations were undertaken to see how the body moved when an able-bodied man used some of the most common tools. These tools were usually linked to the trades that these ex-servicemen were being taught in the workshops at the limb fitting centres – eg saws, files, general woodwork tools. These observations were then used to inform the adaptation of tools for the men who had lost limbs. The blueprint above is an example of suggestions for one such tool.

The above is just a brief insight into the basics of the artificial limbs being manufactured for injured ex-servicemen in the First World War. The number of men returning from the war in need of these new limbs created an environment where more adaptation and experimentation could be undertaken – something we see particularly with the shift from wooden limbs to metal limbs. Much of this experimentation took place at the end of the war and into the interwar period, and we see many of the same materials and designs being used into the Second World War.

This article was excellent and served to remind of our need and duty to care for disabled persons.

My father Pte Henry William Harris, Rifle Brigade had an artificial arm It was far too heavy to wear and was a “toy” up in the attic.

My father lost a leg in 1942 in the North African desert fighting in the 8th army. For the rest of his life he used an artificial leg from Hangars at Roehampton.

When he died I took his limbs to the hospital at Roehampton for use abroad. If there is anything I can do to help Louise in her researches , please contact me.

I have an ancestor during WW1 lost his leg and was waiting for a prosthetic leg

I am not sure of his proper name

He was known as bunny last name Nash

Lived in london east end