This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

Housing in the 1920s

Following the First World War, the British government was increasingly concerned about the health and security of the nation. Conscription had revealed significant health problems among many potential recruits and the authorities also feared increasing social unrest, particularly in light of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

One particular area of concern was the poor state of housing and the unhealthy living conditions of the working classes. In cities across the country, many lived in crowded slums which were in a poor state or repair and fostered the spread of disease. Housing costs were also high and there was a fear that this poor housing could lead to social unrest.

With the coming of peace in 1918, many believed that the new decade needed to be one of renewal and social improvement, one which would usher in a new kind of society. The government promised ‘homes fit for heroes’ and put legislation in place to try to address the housing problem.

The Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 allowed local authorities to clear slum housing and submit plans for new housing estates. New housing was to be built to specific standards, incorporating indoor bathrooms and gardens.

Slum housing and ‘unhealthy areas’

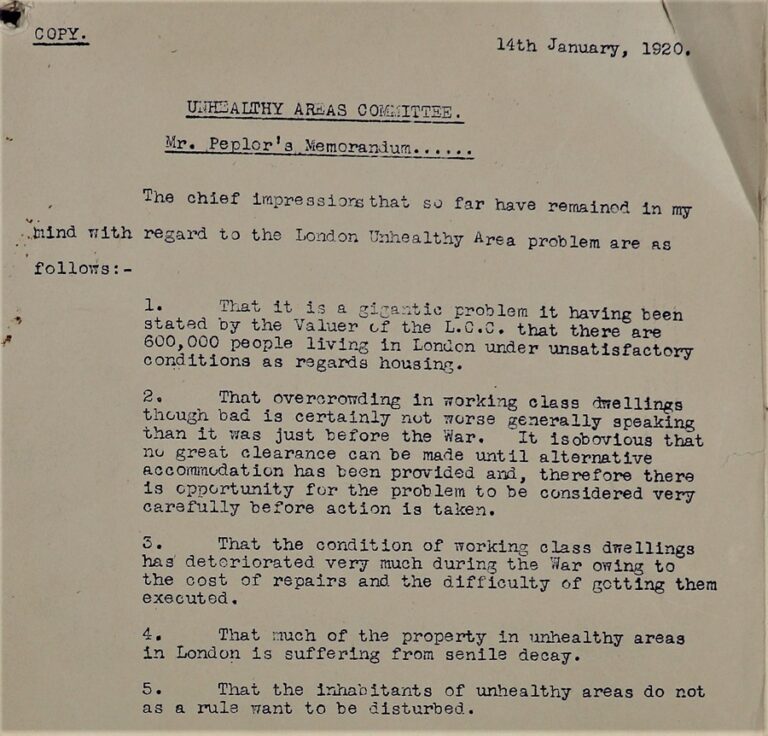

The Ministry of Health established an Unhealthy Areas Committee, chaired by Neville Chamberlain, to assess the extent of the housing problem and make recommendations regarding the clearance of slums and the building of new housing. A memorandum dated 14 January 1920 stated that:

‘It is a gigantic problem … that there are 600,000 people living in London under unsatisfactory conditions as regards housing … The condition of working class dwellings has deteriorated very much during the War owing to the cost of repairs and the difficulty of getting them executed.’

The committee recommended that the ideal solution was to move populations out of crowded urban areas and establish new communities, as had been achieved in some areas through the garden city movement.

But the committee also conceded that each town and city had its own particular circumstances and local authorities needed to take responsibility for identifying unhealthy areas, making compulsory purchases, clearing slum dwellings, re-housing people responsibly and building new housing.[ref]The National Archives, Final Report, Unhealthy Areas Committee. Catalogue ref: HLG 101/258B.[/ref]

Ossulston Estate

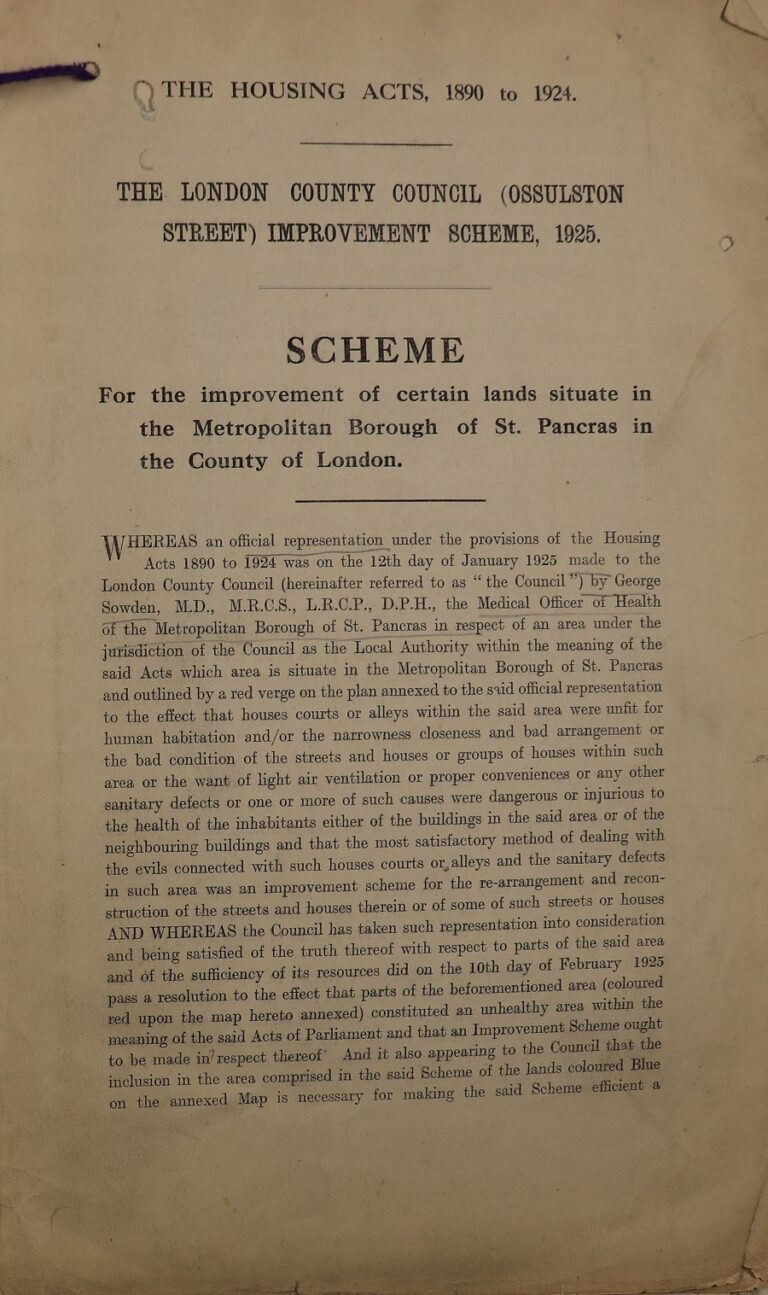

In 1925, the London County Council proposed a scheme to improve housing in Ossulston Street in St Pancras, North West London. It was designed ‘for the improvement of certain lands situate in the Metropolitan Borough of St. Pancras in the County of London’. This scheme involved the clearing of slum housing and the construction of a new housing estate.[ref]The National Archives, Ossulston Street St Pancras Improvement Scheme Order. Catalogue ref: HLG 47/920.[/ref]

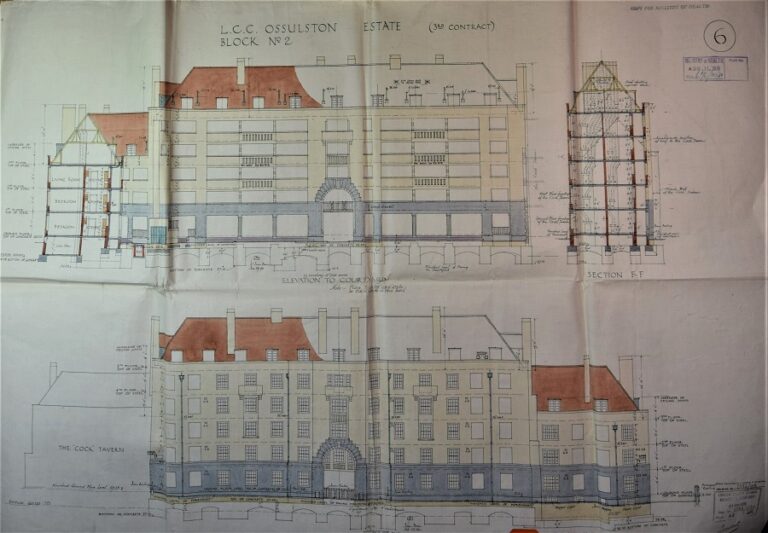

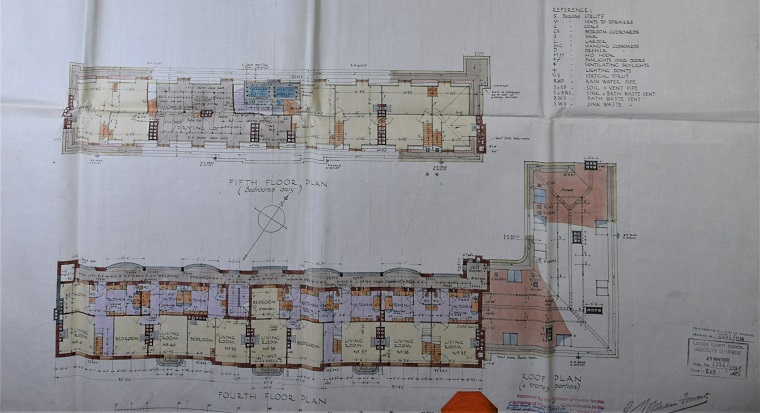

The estate was designed by G Topham Forrest in the form of modernist blocks built around three courtyards. It included 310 flats in total and boasted a supply of electricity. Neville Chamberlain, who had been appointed Minister of Health in 1923, laid the foundation stone on 1 February 1928.[ref]The National Archives, ‘Court Circular’. The Times, 1 February 1928, p. 17. The Times Digital Archive. Accessed 19 Jan 2022.[/ref]

The National Archives holds plans of the new estate and records detailing the arrangements for the compulsory purchase of property in the area.

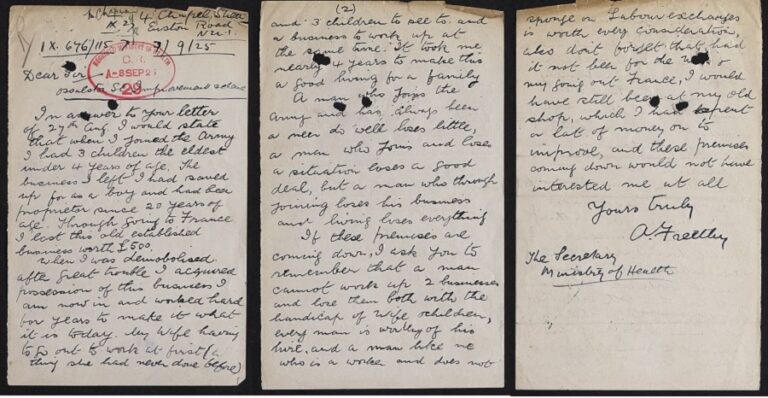

Arthur Freethy’s objection letter

After detailing the plans for the compulsory purchase of properties in the area, the Council received objections from a range of property owners. One poignant letter was from Arthur Freethy, who owned a tobacconist shop on Chapel Street. In his letter he explained that he had previously owned a business worth £500 before the First World War, but on joining the Army and going out to fight in France, he had lost this business. And now, the Ossulston Estate project was threatening to destroy his new business, which had taken him four years to build up.[ref]The National Archives, Letter from Arthur Freethy to the Ministry of Health, 7 September 1925. Catalogue ref: HLG 47/920.[/ref]

He wrote:

‘When I joined the army I had 3 children the eldest under 4 years of age. The business I left I had saved up for as a boy and had been proprietor since 20 years of age. Through going to France I lost this old established business worth £500. When I was demobilized after great trouble I acquired possession of this business I am now in and worked hard for years to make it what it is today. My wife having to go out to work at first (a thing she had never done before).

A man who joins the army and has always been a ne’er do well loses little, a man who joins and loses a situation loses a good deal, but a man who through joining loses his business and living loses everything. If these premises are coming down, I ask you to remember that a man cannot work up 2 businesses and lose them both with the handicap of wife and children.’

Arthur Freethy appears in the 1921 census living at 4 Chapel Street with his wife Helena and their three children: Arthur (age 7), Phyllis (age 6) and Reginald (age 5). His occupation is listed as ‘own account – tobacconist’ and his wife is working as a ‘daily help’ at the Grand Hotel, Trafalgar Square.

Trauma and progress

Despite objections, the Ossulston Estate was completed in 1931 and still stands today as a Grade II listed building. Although we do not have any further information about what happened to Arthur Freethy’s shop, we know that he left the area after his property was purchased and demolished. In the 1939 Register, we find him living in Harrow, however two of his sons are listed as living at Chamberlain House, one of the new buildings in the Ossulston estate.

Arthur Freethy’s story demonstrates very clearly the trauma experienced by those caught between the First World War and the radical changes of the 1920s. Like many other housing projects in the era, Ossulston Estate did greatly improve living conditions. However at the same time, the process of making these improvements could bring traumatic upheavals to those already living in the area, many of whom were still recovering from the impacts of the First World War.

Arthur Freethy’s original letter is on display at The National Archives’ exhibition The 1920s: Beyond the Roar, on now until 11 June.

To learn more about the early development of housing in the 1920s, please see our blog, The birth of council housing.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

Really interesting, thank you. Quite by chance, I discovered only a few days ago that my great uncle and his family were living in Ossulston Street in 1911 and I wondered what it was like back then. This certainly gives a clear picture of it!

i like it