I am asked on a daily basis to describe who I am: one day I am an academic, another a researcher, and then a textiles practitioner. My name is Rose Sinclair and I am all of the aforementioned, but it is my researcher role that brings me to the archive, to seek out fabrics in a place perhaps often perceived from the outside as being full of paper.

Beyond the façade of bricks and mortar is another world and space in which I become so engaged time drifts away. If I could relocate my studio practice with all its ‘stuff’ for a month to just start to examine the designs, understand the prints, weaves, embroideries, in context, location iconography, one word… wow. I would be in design heaven.

Using my academic perspective I see the benefits of students seeing, handling, understanding the evolution of design, thinking against a backdrop of cultural evolution extending the reach of the archive into teaching and learning into creative practice with students, who on a daily basis curate and archive their own lives in digital spaces.[ref]1. D Gauntlett, ‘Making is connecting: The social meaning of creativity from DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0’, (2011)[/ref] As a researcher I am interested in the ‘before and after‘, the stories and the memories, times before and times after. Textiles from an archive can be one vehicle that can tell those stories.

‘…but in archives, though the bundles may be mountainous, there is not very much there (…) the archive is made from selected and consciously chosen documentation from the past and also from the mad fragmentation that no one intended to preserve and just ended up there.'[ref]2. C Steedman, ‘Dust: The Archive and Cultural History’, (2001)[/ref]

As a researcher, my first entry into the archives was one of awe and thinking, ‘wait a minute: how on earth will I be able to locate what I need, and how can paper lead me to textiles?’

Indeed Steedman’s quote could leave you thinking an archive is just made up of mounds of paper, and you will be sitting in room surrounded by mounds of books; that can happen and does happen. I call it serendipity that archives also contain cloth and other ephemera, fabrics, which are tangible things, material objects, which speak of approaches to technology, design, process, practice, making, crafting. The designs can also speak about how culture can be interpreted and reinterpreted.

The design register is a form of archive that allows an exploration about the design practice of British manufacturing companies that designed, crafted and then manufactured products for distribution not only in the UK but across the world. Companies sought to register their designs, and in some cases re-register after the five year registration process elapsed, speaking of the popularity of a design or product. The register speaks of design taste, the changing technology of manufacturing practices, colour, dyes, design motifs, aesthetics tastes, responses to market or markets, or the opportunity to perhaps usurp the local market.

As a textiles practitioner it is material object that triggers my research question, my practice, my ‘other’ knowledge. The design register is one such archive, of 3 million pieces of fabric. Once you realise that the numbers in the catalogue relate to a designed object, ephemera, it gets exciting as a box is delivered to your desk, you undo the ribbon, and you say ‘wow’.

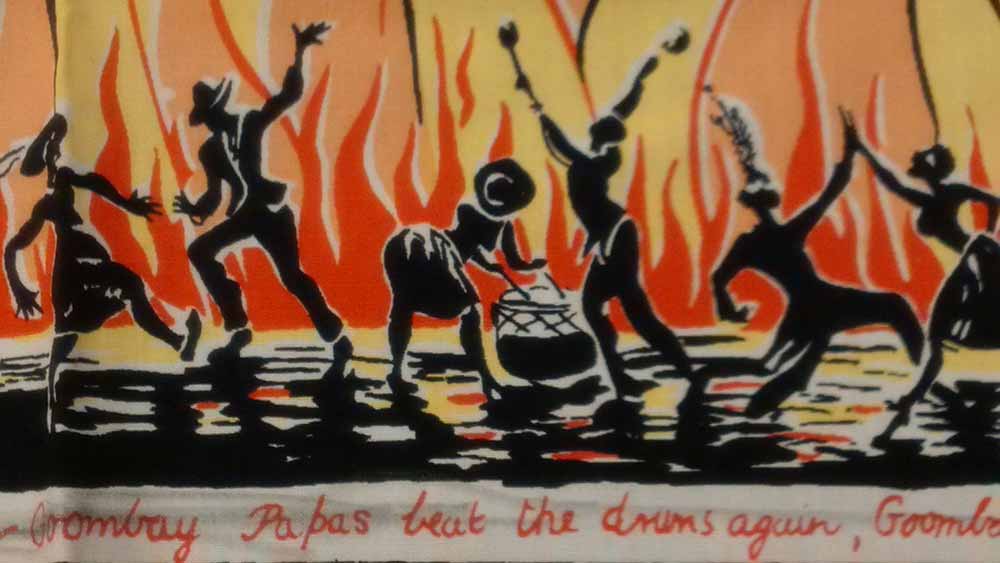

My first delve into the archive was assisted by Julie Halls and Sandra Shakespeare at The National Archives. I was looking for fabrics that highlighted the migration process from Caribbean to the UK, and what I located was fabric that seem to indicate design operating in the other direction, starting in the UK and going to the Caribbean and the wider diaspora. This fabric, and its design, has lead me down other research paths, both through The National Archives and other archives. This fabric raises questions of material culture, object speaking, design history. Why would such a fabric – designed by an Irish company, made from Sea Island cotton, printed in Manchester – depict designs that showcase Caribbean cultural traditions such as Junkanoo and the Goombay dance? The history of the company that created the fabric also makes interesting reading, adding another layer to an already diverse range of questions.

Orange with Goombays, design registration 451013 (catalogue number: BT 52/6654)

Note however the first visit located one fabric. It would take more research and further visits to locate further fabrics.

For me as a practitioner the excitement is that I can use fabrics in a creative workshop that speak directly to cultural traditions I know of from stories from my own childhood or background. I am excited to be sharing this workshop on 12 November 2016 with other makers, researcher and crafters.

Blue and white Junkanoo, design registration 474392 (catalogue reference: BT 53/161)

Archival research is not fast, but it throws up the unexpected. It highlights for me the place the archive plays in the research practice space, both in the institution and also in the space of the practitioner, as you seek to interpret the findings outside of the space of the archives, working from your own photographs, notes, sketches, images, making sense of the wider and broader story of making, and its relation to the wider world. More will be revealed about these fabrics and their provenance at my forthcoming talk.

My journey to using The National Archives started at the very beginning of my research, in trying to locate documentation about the Caribbean, especially visuals related to textiles and materials practice, which lie at the heart of my research. My work is also informed by oral history, which relies on history and memory, another form of what I call in my research an ‘archive’. The Discovery catalogue allowed searching of the incoming passengers lists, allowing me to corroborate participants migration stories but also to collate data about professional status of women from the Caribbean coming to England in the 1950s and 1960s. The ‘Caribbean through a lens’ project allowed discussion about the differences between life ‘back home’ and life in England, as well as compare and contrast images from participants’ photo albums.

The heart of my research however revolves around fabric, and its place in the migration journey of ‘Caribbean’ women and how they used the textiles to craft their domestic space. As a textiles practitioner, any opportunity to engage with actual fabric samples offers the opportunity to connect with material culture, practice, memory and the lived experience on another level. Memories enable connections with the material culture, the corporeal, the tangible objects constructed by humans, the lived-with and the traces left behind[ref]3. P O’ Toole and P Were, ‘Observing places; using space and material culture in qualitative research’ in Qualitative Research vol. 8, no. 5 (2008): 616-634[/ref], objects can have a voice or be presumed to talk.[ref]4. D Miller, ‘The Comfort of Things’ (2008)[/ref] The fabrics in the design register in The National Archives offer the opportunity for me as practitioner to locate another voice.

I suggest that we can perhaps navigate our roots or routes in and through the textile objects that we make, thus leaving behind traces of ourselves, memories of the lived self, a sensory self, a tacit self and even perhaps a haptic embrace. Textiles are part of us and we of them. At a recent conference workshop I asked delegates to list the ten points at which textiles made a difference to their lives and why, and what were their most treasured items. Many respondents listed making as one of the areas, alongside making with a relative, with memories of fabrics people dear in their lives had worn or passed down.

Doing history is about making stories, creating interpretations. Interviewees make and create stories which are a form of narrative of (his)story or her(story), making use of the archive to create a ‘oral double interpretative practice’[ref]5. L Sardino and P Partington, ‘Oral History in the Visual Arts’, (2013)[/ref], allowing a questioning of aesthetic styles and domestic practices (crafts). [ref]6. M McMillan, ‘De Mudder Tongue’ in ‘Oral History in the Visual Arts’ (2013): 25-35[/ref]

Doing archival research is about uncovering stories, allowing layers to come together, combining both what we know and what we do not know, to form new knowledge. As a practitioner, the design register as a collection speaks to me and my practice, and allows my research to develop through what I term as a ‘double interpretative practice’ combining the known and unknown, the spoken and the unspoken, the written and the unwritten, thus creating new narratives and new stories, new designs.

My thanks to Sandra Shakespeare, Julie Halls and Vicky Iglikowski at the National Archives.

Rose Sinclair will be leading a presentation and crafting workshop in response to the fabrics in the BT Design Register on Saturday 12 November 2016 – book your ticket. Find out more about her work or follow her on Twitter: @dorcasstories

I assume the reference number 52/6654 is supposed to be BT 52/6654.

This was an oddly exhilarating read; silly as it may sound, there was such a thrill in the sense of discovery as the author explained her research unfolding. I’m feeling so inspired after reading it, thank you!