Archives are integral to our understanding of artists and their work. We can delve into known records again and again, find out new things or reinterpret documentation which continues to enrich our knowledge in various ways. We can find out more, not only about the artist’s public standing and reception but also their personal lives which often remain private or hidden during their lifetime. Archives can often provide a link between the artist and the work, providing a documentary narrative which itself is fascinating.

Presented here are a selection of documents from collections held at Tate Archives and The National Archives [ref] 1. Records related to Barbara Hepworth are scattered in various archives. [/ref] which reveals different aspects of the personal and professional life of Barbara Hepworth.

Tate Archive: Barbara Hepworth’s personal life – Morwenna Roche

The Tate Archive has recently finished the project of cataloguing Barbara Hepworth’s papers (generously funded by Tate Members and the Estate of Barbara Hepworth), which provide a fascinating and rich insight into her life and work.

The papers were neatly divided into two collections: Correspondence of Barbara Hepworth (TGA 965) and The remaining personal papers of Barbara Hepworth (TGA 20132). Together these two collections provide a fascinating and rich insight into the personal and professional life of the sculptor, particularly from the 1940s onwards.

Barbara Hepworth (c 1927), Document reference: TGA 200314/5/1/3. Tate Archives. © Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

Hepworth’s life was very varied both professionally and personally. Unfortunately not many records survived from her early life in Yorkshire and when she was studying at Leeds School of Art (1920-1921) with Henry Moore. There are just a couple of good examples from her very early life in the collection; her school certificates from Wakefield and the piano certificates showing she passed the Advanced Pianoforte test in 1920.

Meeting John Skeaping

Whilst studying at the Royal College of Art (1921-1924), she won the West Riding Travel Scholarship and went to Rome. There she first met and subsequently married the sculptor John Skeaping, a Scholar in Sculpture at the British School in Rome.

The couple lived together in Rome for a year, and then moved back to London due to Skeaping’s ill health. Their son Paul was born in 1929, and Hepworth created the sculpture, Infant, shortly after his birth (currently on show in the sculptor’s exhibition at Tate Britain). One of the few items from this period of her life in the Tate Archive is the photograph of the sculpture of Hepworth made by Skeaping during their time in Italy. The original sculpture has now been lost so this photograph is invaluable.

Photograph of ‘Head of Barbara Hepworth’ by John Skeaping, (c1925-1927). Document reference: TGA 20132/4/9, Tate Archives. ©Estate of John Skeaping; photography © reserved.

Hepworth and Nicholson

The Tate Archive collections contain a large amount of correspondence with her second husband the abstract painter Ben Nicholson. They met in 1931 and quickly fell in love. Both were still married at this time, Hepworth to Skeaping and Nicholson to Winifred (nee Dacre). However, Hepworth divorced Skeaping in 1931 [ref] 2. The divorce case file is held at The National Archives in J 77/2964/1565. [/ref] and three years later the Nicholson-Hepworth triplets Simon, Sarah and Rachel were born.

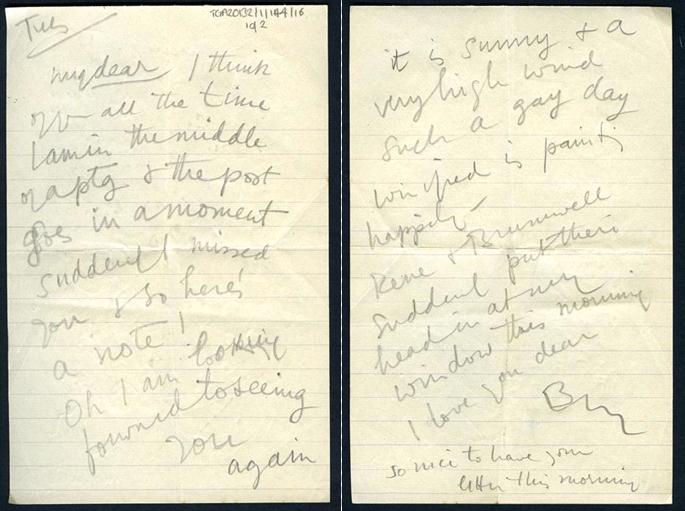

The couple finally married in 1938, after Nicholson’s divorce from Winifred. The correspondence covers the start of their relationship, the birth of the triplets (which was rather a shock to both parents), establishing the family and their respective careers in St Ives, and sadly after the war, the deterioration of their relationship.

Hepworth’s letters to Nicholson can also be viewed in the Tate Archive, in the Nicholson collection TGA 8717. The couple divorced in 1951. Hepworth stayed in St Ives establishing herself there, and Nicholson moved to Switzerland with his third wife Felicitas Vogler.

Letter from Ben Nicholson to Barbara Hepworth (c 1930s). Document reference: TGA 20132/1/144/16, Tate Archives. ©Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

The National Archives: Barbara Hepworth’s professional life – Ann Chow

The National Archives hold various records related to the professional life of Barbara Hepworth which complement collections held in other archives. Much of this is contained within the administrative files of exhibitions records of the Festival of Britain (1951) and the British Council.

The exhibitions records of the Festival of Britain (1951) and the British Council

Exhibition records not only reveal the amount of work that is put into the organisation of temporary exhibitions by employees and others involved, but also show the way in which artists are involved in shaping the exhibitions right at the start and up to the point of installation. They also reveal the interactions between the artist and the employees of government bodies and related agencies (and their opinions) and what is considered as ‘fashionable art’ at a given point in time.

Hepworth was already established as one of Britain’s leading sculptors by 1965. She had represented Britain in the Venice Biennale (1950) [ref] 3. As mentioned in a previous blog on Hepworth and the Venice Biennale. [/ref] and had won the Grand Prix at the Sao Paulo Biennial of 1959. The National Archives hold various British Council files relating to the organisation of these exhibitions. Taken as a whole they indicate Hepworth’s growing international profile at various stages in her career. As individual files, they provide insights into the painstaking labour of organising art exhibitions.

The records of the Festival of Britain held at The National Archives reveal various aspects of Hepworth’s artistic practice and the wider exhibiting of modern art in post-war Britain. They place her art in context with other artists and designers working at the time, such as fellow sculptors Jacob Epstein and Henry Moore, artists such as Prunella Clough and designers such as Robin Day.

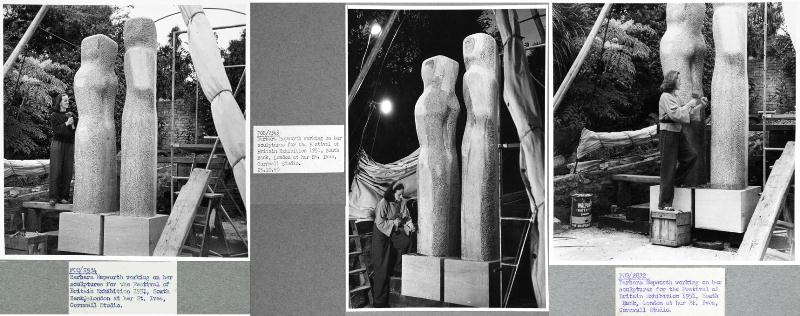

Festival of Britain photographs of Hepworth working on Contrapuntal Forms. From left to right: Document references: WORK 25/204 (2934) (2) WORK 25/204 (2821) (3) WORK 25/204 (2822), The National Archives.

The series of photographs from the Festival of Britain collection held by The National Archives [ref] 4. This selection is part of a wider photographic collection held in 35 albums taken by the Festival Office Photographic unit. We can assume that these photographs were produced to record coming together of the event but it is not clear if they were intended for publication. [/ref] presents the artist working at her St Ives based Trewyn Studio. The above photographs show her working at different stages on the sculpture Contrapuntal Forms commissioned by the Arts Council (the sculpture was finished in March 1951). You can see how she approaches sculpting of the large piece of Irish blue limestone and the process of the production over time. Although she hired assistants for the first time, they are not pictured in the series of photographs.

Hepworth’s status as an international artist

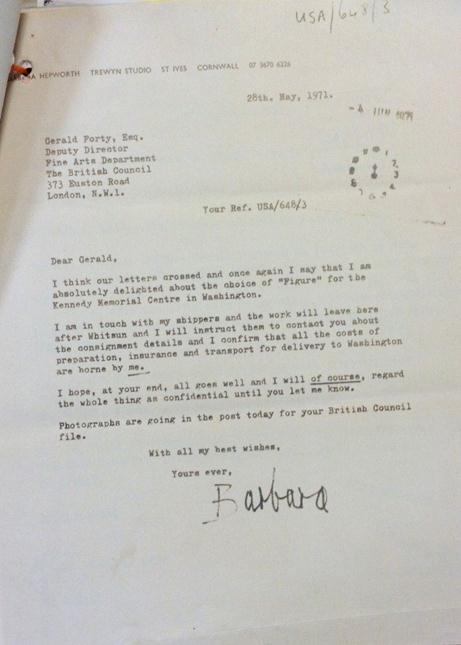

Other records held at The National Archives show her as an established international artist in her later life. Administrative files relating to the organisation of the presentation of Hepworth’s Figure in Kennedy Memorial Centre in Washington in 1971 (four years before her death) reveal the decision making process behind the selection and the final recommendation of the Special Sub-committee of the British Council Fine Arts Advisory Committee under the chairmanship of Norman Reid. Hepworth’s sculpture Figure was selected as Great Britain’s official gift for the John F Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts.

A letter from Hepworth which reveals her delight that her sculpture Figure has been selected to be displayed in the Kennedy Memorial Centre in Washington. Document reference: FCO 13/449, The National Archives. ©Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

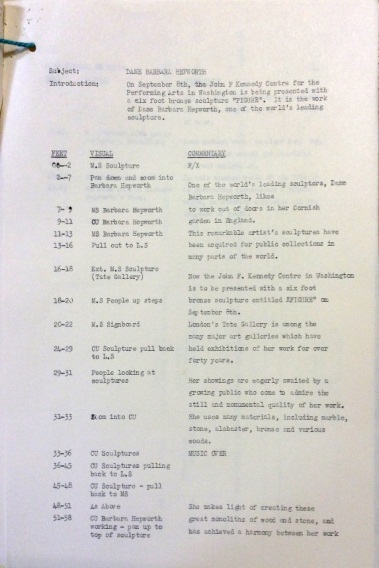

Film production papers for a short documentary on Hepworth (1971) show the event from a different angle. It is interesting to note how she is presented to the public eye. As written in the documentary script (see below): ‘in this teenage word of the 70s it is refreshing to encounter a talent, in maturity expresses the dynamism of youth’.

Film production documents for documentary on Hepworth (1971). Document reference: INF 6/1080, The National Archives.

Surviving production notes such as the above example, [ref] 5. We do not hold the actual footage [/ref] along with other productions notes in file INF 6/2371 for another documentary in 1973 and the surviving footage of Dudley Shaw Ashton’s film Figures in a Landscape made 18 years earlier show how a different medium presented Hepworth as an artist in the public eye.

Interested to find out more?

Listen to a podcast of talks on Barbara Hepworth and selected archives with speakers from The Tate, Tate Archives and The National Archives.

A selection of archives related to Barbara Hepworth from The National Archives will be on display in The Keeper’s Gallery until November 2015.

Other related Barbara Hepworth events at The National Archives:

- Family event: Artist in the Archive: create a sculpture inspired by Barbara Hepworth

- Webinar on archives and the arts: the Festival of Britain

What’s happening elsewhere?

The exhibition Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World at Tate Britain (June – Oct 2015).

A ‘Show and Tell’ on Barbara Hepworth on 7 August, 12:30-14:30 at Tate Library and Archive.

The exhibition Hepworth in Yorkshire and A Greater Freedom: Hepworth: 1965-1975 at The Hepworth Wakefield.

Most fascinating account -many thanks. There exists another photograph of Skeaping’s ‘Head of Barbara Hepworth’ showing the entire bust, which may be of interest; please contact me and I shall gladly send a copy if you are interested. Best wishes.

On the 19 July 1970 or close to that date Dame Barbara wrote to me regarding the response to her statue ‘The Crucifixion” which she had presented to the Dean of Salisbury Cathedral. At that time I was editing a small pamphlet and I was interested to hear Dame Barbara’s thoughts on the comments made in the local press. The statue was not received well by some who became vocal. I, however, did like the statue. Sadly her reply wasn’t returned to me from the pamphlet typists. I would very much like to have a copy of her letter to accompany the envelope which I still have. The date on the envelope is the 20 July 1970 posted from St Ives. I have moved many times since that date and now live in Salisbury, I have also added my wife’s family name to mine. After it was vandalised in the 1980/90s the statue disappeared from sight. A decade ago I was walking passed Winchester Cathedral, and lo there it was. However, it now seems to have been moved yet again! Should a copy of Dame Barbara’s letter could be forthcoming I would be very grateful. I will send my current address if and when required.

Kind regards

B.J. Matthews-Keel