A new law on antiquities was approved in Iraq in 1936. Drafted by Sati al-Husri, the first Iraqi Director of Antiquities, it was rather generous towards foreign archaeologists. In fact, it was more generous than similar laws in neighbouring countries. However, it was much less favourable to foreigners than the previous law had been. As I have explained in another blog post, it didn’t go down well in archaeological circles. A lot of archaeologists, Max Mallowan or Leonard Woolley, for instance, decided to focus on Syria rather than Iraq.

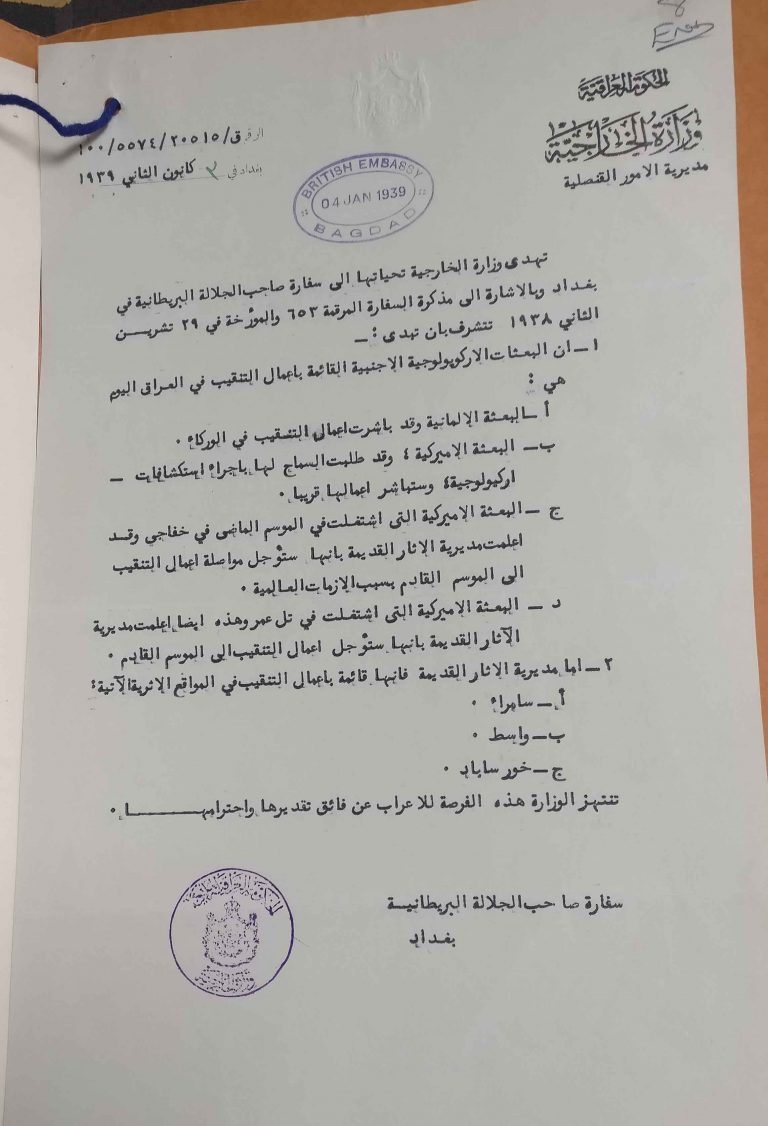

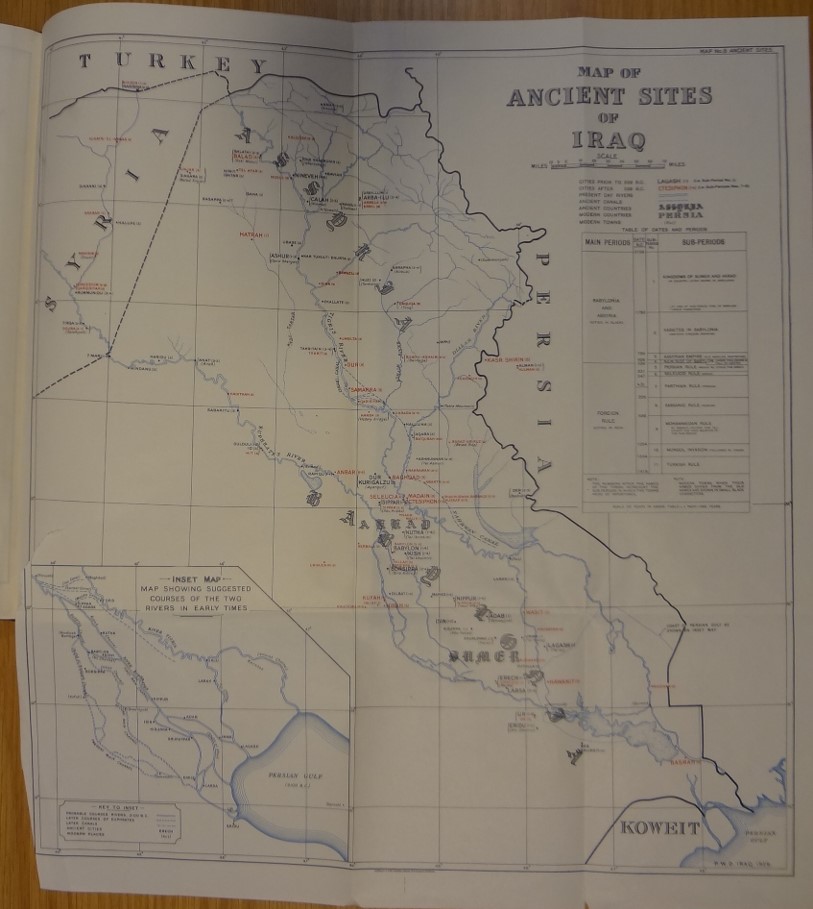

As a result, in 1939 there were relatively few foreign missions carrying out work in the country. There was a German mission at Uruk, an American mission doing some vague prospection work, another American mission at Tutub (who wouldn’t reapply the following year for a permit due to international tensions), and yet another American mission at Tel Omar (who wouldn’t reapply either). The Iraqi Department of Antiquities was itself conducting excavations at Samarra, Wasit, and Dur-Sharrukin (FO 624/14).

Letter from the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the British Embassy in Baghdad, 3 January 1939 (catalogue reference FO 624/14)

If you have read some of my other blog posts, you know I like to mix archaeology and politics. When I started looking at the Second World War in Iraq, it first seemed that archaeologico-diplomatic activities had been largely put on hold. It was annoying (for blog-writing purposes), but perhaps logical. After all, Britain was at war and had more urgent matters to attend to than Assyriology.

Fear not: I was rescued from my blog angst by a Dr Julius Jordan, and then, digging deeper (no pun intended), I started finding interesting titbits.

Julius Jordan was a German archaeologist. He had excavated in Assur, Sippar and Uruk, and had been Director of Antiquities – and of the Baghdad Museum – until 1934. Jordan was also a Nazi. And not just any Nazi party member, but the Head of the local Nazi party in Iraq. The Nazi party had established branches everywhere in the world as part of the Auslandsorganisation (which numbered about 580 cells by 1938), and Jordan was therefore coordinating Nazi propaganda in Iraq. It was a rather well-known fact, even though he had made a vague attempt at disguising it.

When he was replaced by Sati al-Husri, he was kept on the payroll of the Department of Antiquities as a technical adviser. His contract came to an end in November 1938, but he stayed in Iraq – ostensibly as the Representative of the Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft and as an archaeological attaché to the German Legation. Ponsonby Moore Crosthwaite, of the Eastern Department at the Foreign Office, noted: ‘An archaeological attaché must be unprecedented! But as Dr Jordan has for years been the head of the party in Iraq, the camouflage is painfully thin.’ (FO 371/23202)

- Minute by Crosthwaite, 7 January 1939 (catalogue reference: FO 371/23202)

- Minute by Crosthwaite, 7 January 1939 (catalogue reference: FO 371/23202)

Jordan and the German ambassador – Fritz Grobba, an accomplished linguist – were at the centre of Nazi propaganda in Iraq before the war erupted. According to a report on German propaganda activity sent to the Foreign Office by the Air Liaison Officer, Jordan held considerable power. (FO 371/23203)

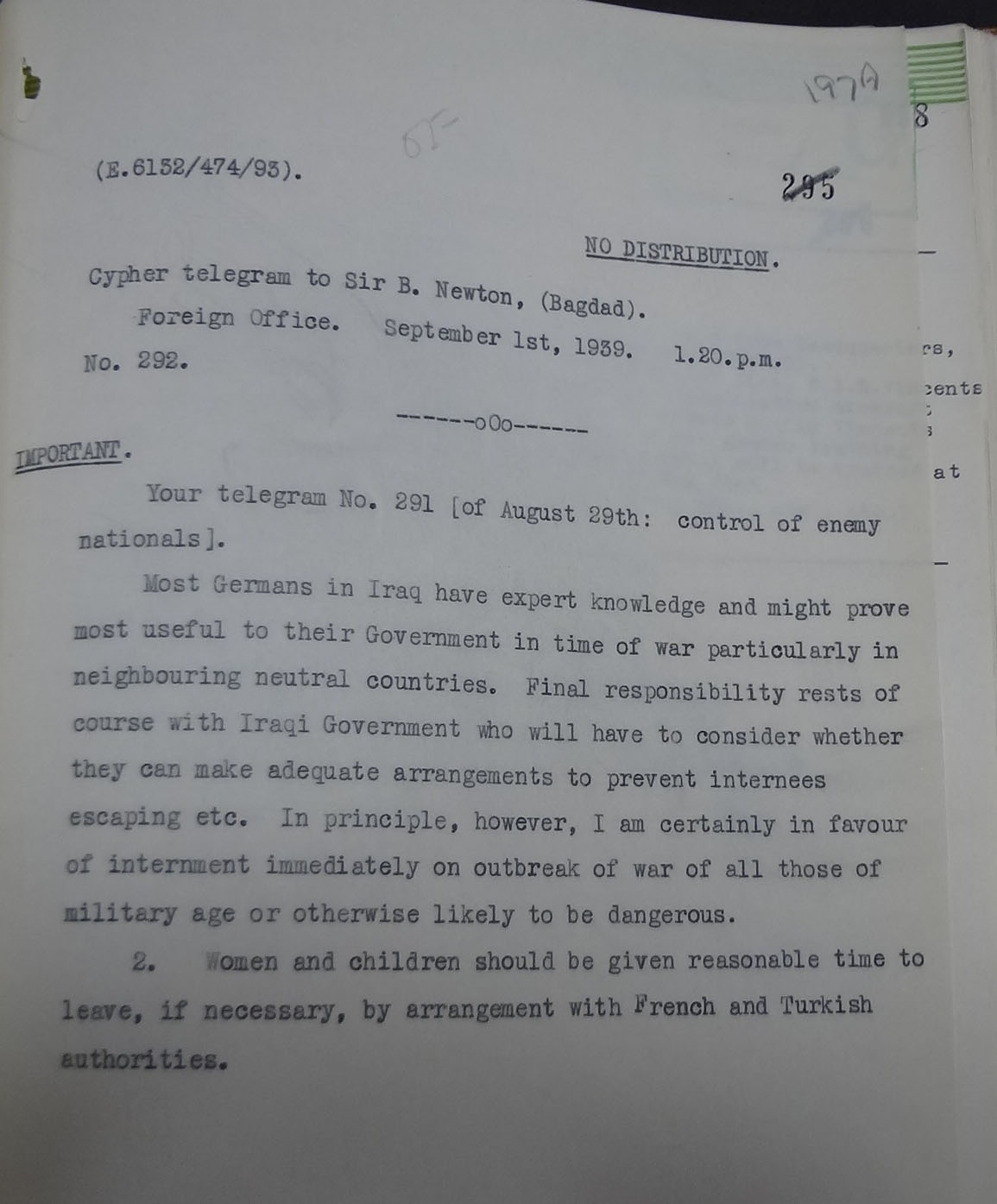

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. On this day, the British Ambassador in Baghdad, Sir Basil Newton, reported to the Foreign Office: ‘Most Germans in Iraq have expert knowledge and might prove most useful to their Government in time of war’. The Foreign Office would later note – with, I think, a bit of envy – the linguistic skills of the German legation in Iraq (FO 371/23211).

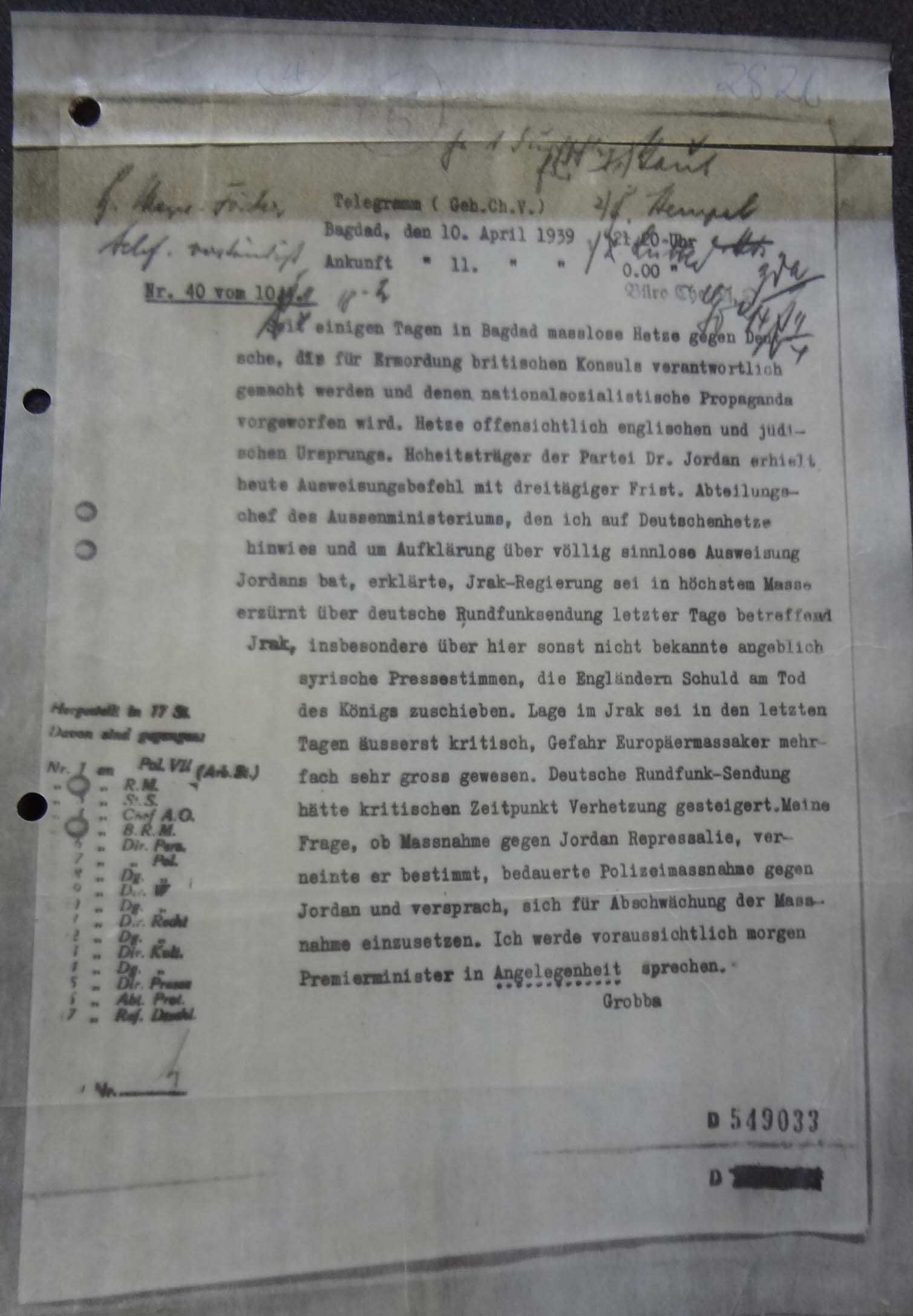

It didn’t go well in Iraq for the German experts. On 4 April 1939, a crowd gathered in Mosul to mourn the late King Ghazi. This crowd was worked into a rage by agitators who declared that the British Government were in some way responsible for the King’s death. (He died in an incident involving the sports car he was driving, but the rumour was that he had been assassinated on the orders of the pro-British Prime Minister, Nuri al-Said).

The crowd stormed the British Consulate. The Consul, Monk Mason, was murdered before the local authorities had time to act. Several young men were arrested after distributing leaflets stating that Britain was responsible for the death of the King. It turned out that these men were somehow linked to Jordan.

Julius Jordan and all the German archaeologists were given four days to leave the country. He left Baghdad on 17 April 1939. As early as the summer of 1939, Grobba tried to secure his return to Iraq. Jordan said he was writing a book on archaeology in Iraq and wanted to return to complete it. The request was denied. So, technically he wasn’t there during the war, but it is interesting to see old patterns being repeated, and archaeologists being used as intelligence officers.

Grobba himself would leave the country on 6 September 1939; he returned in 1941, under a false name, to assist Rashid Ali al-Gailani with his (short-lived) nationalist coup (GFM 33/996).

Telegram from the German embassy in Baghdad to the Auswärtiges Amt in Berlin, 10 April 1939 (catalogue reference: GFM 33/996)

In October 1939, Nuri al-Said declared that the war might be an opportunity to achieve national aspirations. This also applied very much to archaeology. When Sati al-Husri had taken over from Jordan as Director of Antiquities in 1934, he had decided to focus excavations on the Islamic past of Iraq – notably the Abbasid period. Various reasons have been suggested: these Islamic monuments had traditionally been neglected by foreigners, they were closer to the surface, or they were easier to study… This focus was also in line with the pan-Arabism prevalent at the time. Still, Iraqi archaeologists were being trained to excavate Ancient pre-Islamic sites. Fuad Safar, for instance, worked with Seton Lloyd at Tell ‘Uqair in 1940-194. Rashid Ali al-Gailani’s coup of April 1941, which started a brief Anglo-Iraqi war, put everything on hold. The Nationalist forces were defeated, and Sati al-Husri was forced into exile (FO 371/23212).

Sati al-Husri was swiftly replaced, and archaeological work resumed. With his removal, Iraqi archaeologists spent more time on pre-Islamic, notably Sumerian sites. In 1942-43, for instance, Taha Baqir excavated at Aqar Quf, not far from Baghdad. It may seem a bit strange, but we have to remember that Iraq was not at war at the time. Nuri al-Said was very keen on joining the Allies; the British were a bit less keen as Iraq didn’t seem to want to abide by their conditions. This prompted Crosthwaite to comment:

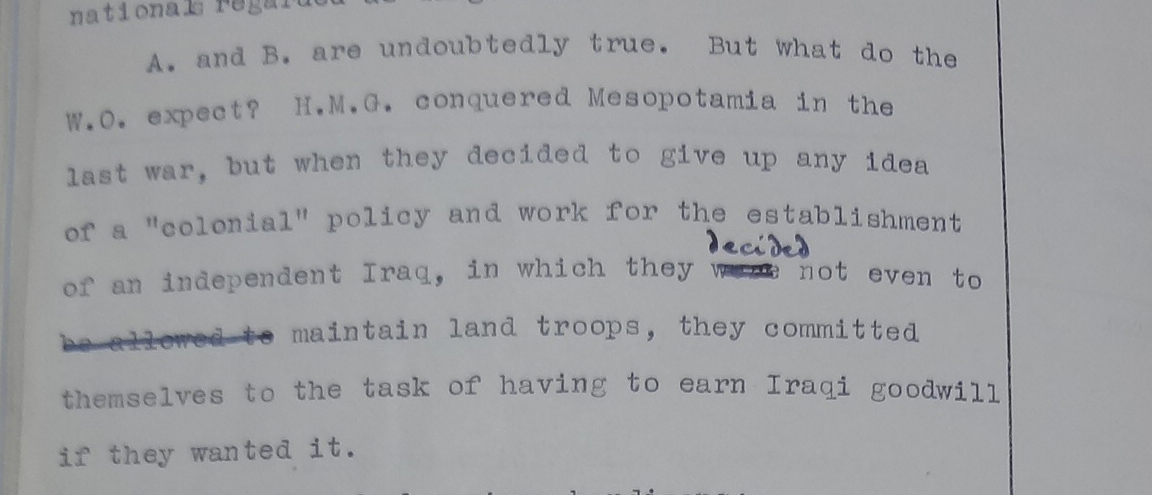

What do the War Office expect? His Majesty’s Government conquered Mesopotamia in the last war, but when they decided to give up any idea of a “colonial” policy and work for the establishment of an independent Iraq, in which they decided not even to maintain land troops, they committed themselves to the task of having to earn Iraqi goodwill if they wanted it. (FO 371/23212)

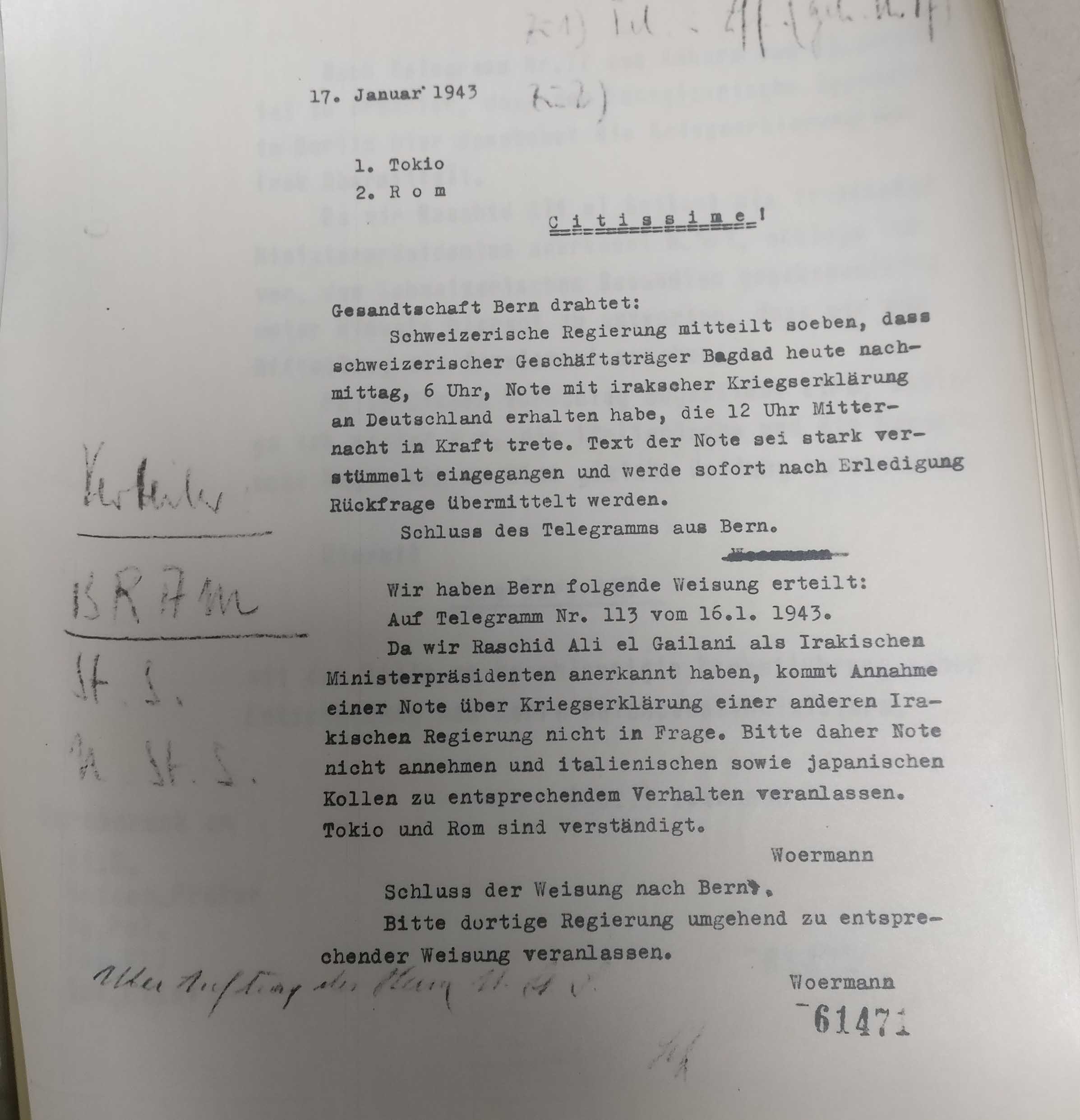

Incidentally, when Iraq did declare war on Germany, on 16 January 1943, Germany initially refused to accept the declaration. Germany stated that it didn’t recognise the government as legitimate and was still backing Rashid Ali al-Gailani. Rashid al-Gailani remained in touch with German officials until the end of the war – clearly both the Nazi Government and the Gailani faction were backing the wrong lamassu (GFM 33/91-92).

Germany refused to accept the Iraqi declaration of war, 17 January 1943 (catalogue reference: GFM 33/91)

While there was no British archaeological mission in Iraq during the war, archaeological preoccupations were never that far away.

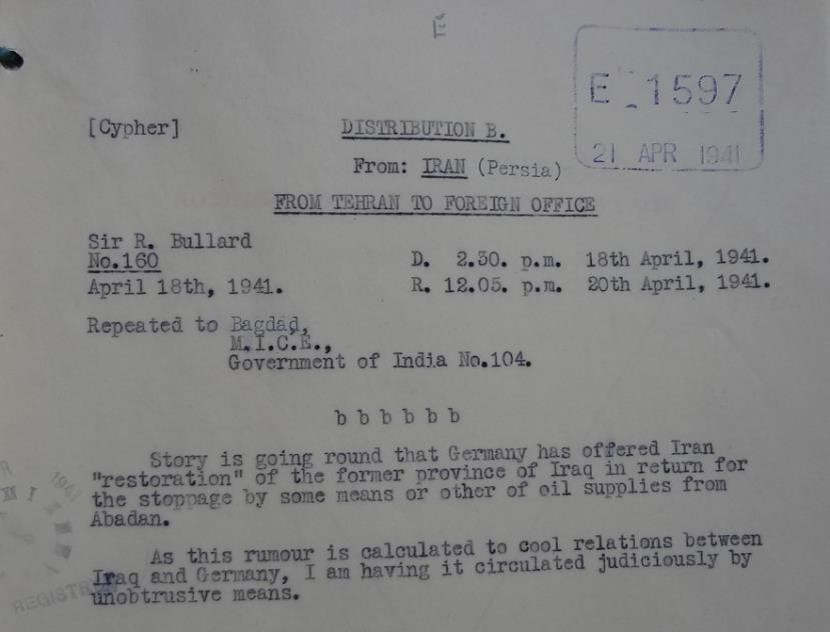

Ancient history was used for propaganda purposes. A rumour was circulated that Germany had offered Iran ‘restoration’ of their former province of Iraq in exchange for the stoppage of oil supplies from Abadan, in the South West of Iran; also that they had invoked glorious memories of the Median Empire, the Achaemenid Empire the Parthian Empire, and so on. It may seem trivial, but it probably had some impact (FO 371/27042A).

Telegram from the British Ambassador to Iran to the Foreign Office, 18 April 1941 (catalogue reference: FO 371/27042A)

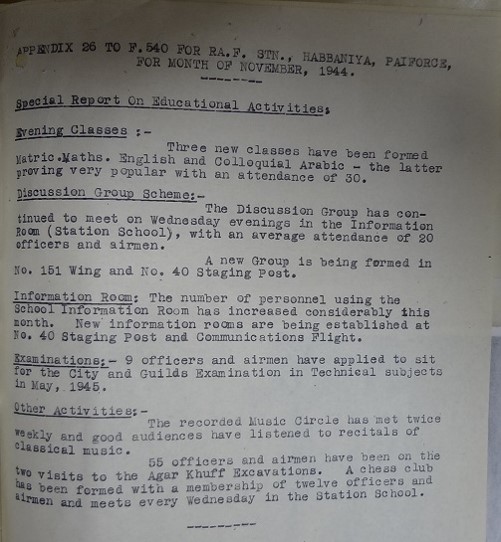

Soldiers, British and Iraqi alike, were treated to archaeological lectures, and frequently visited archaeological sites. I understand that Aqar Quf was always a favourite.

But obviously it was war: sadly, antiquities and ancient monuments sometimes suffered or disappeared. In February 1940, the Iraqi Consul in Washington got in touch with the British Embassy, asking for assistance. They suspected that antiquities were being smuggled out of Iraq into the United States and wanted the American custom officers to warn them if anything came up. Sadly, the American customs authorities were unable, or unwilling, to assist (FO 624/20).

Naji al-Asil, the Director of Antiquities, reported to Assyriologist Gadd, at the British Museum, that considerable damage had been done at Nineveh by an unscrupulous contractor, paid by the cubic metre for broken stone for defence works at Mosul – he had smashed a lot of things to pieces (T 209/10).

Leonard Woolley, who had made stunning discoveries at Ur before the war, was appointed as archaeological adviser to the War Office. He later became part of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives programme – a real Monuments Man. Even though he was sometimes described as having an interest in buildings which did ‘not extend much beyond 500 B. C.’, having him in position showed that the War Office did take the protection of antiquities and ancient sites into account. Although operational considerations obviously remained paramount, the importance of historical heritage was clearly asserted (FO 371/37330).

Al-Asil to Gadd, 25 May 1945 (catalogue reference T 209/10)

In April 1945, Sergeant Shimon Applebaum, who would become a Professor of Classical Archaeology, gave a lecture in Derna, in Libya. He reminded his audience that archaeology ‘aims at enlarging man’s self-knowledge and reconstructing history’ (WO 230/166).

I think that the Second World War really enabled Iraqi archaeology to develop and thrive, and enabled this most interesting shift from the pre-Islamic past to the Sumerian civilisation – from pan-Arabism to Iraqi particularism.

Thank you Dr Desplat for this post (and the others on the archaeology and the Second World War). I am embarrassed to say I have passed over them as they are not fairly and squarely in my fields of interest. And I have to say Indiana Jones hasn’t helped in that respect. However I shall now go back and see what I have overlooked!

i am looking for pte.p.ryan records wo/372/10005 is medal number 41315 is soldier number

Hi Padraig,

Thanks for your comment.

If you are looking for records on a soldier in the Second World War, please be aware that military service records from the mid-1920s onwards are still held by the Ministry of Defence.

You will need to contact Veterans UK for more details by going to the GOV.UK website – see https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/requests-for-personal-data-and-service-records

Access to the service records of people who are still alive or, to a lesser extent, who died less than 25 years ago, is restricted. This is explained in more detail on the GOV.UK website.

If you’d like to get in touch with our record experts by email or live chat, go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/

Kind regards,

Liz.

Dear Dr Desplat,

I really enjoyed your posting. I wish it had been available when I wrote my paper on Aqar Quf before excavation a few years ago (available on Academia). It contains many details and documents I had not known existed. I would be really interested to know if there is any further material on this subject as Aqar Quf (ancient Dur-Kurigalzu – founded c. 1400 BCE) is a very particular study of mine.

Yours

Tim

Could Sati’ al-Husri be identified as Iraqi? I’m not sure he would have agreed with that designation. Perhaps, the first “non-European” director of antiquities (post Bell and Smith). Now, that he would appreciate, ha! Thanks for this. I enjoyed reading.