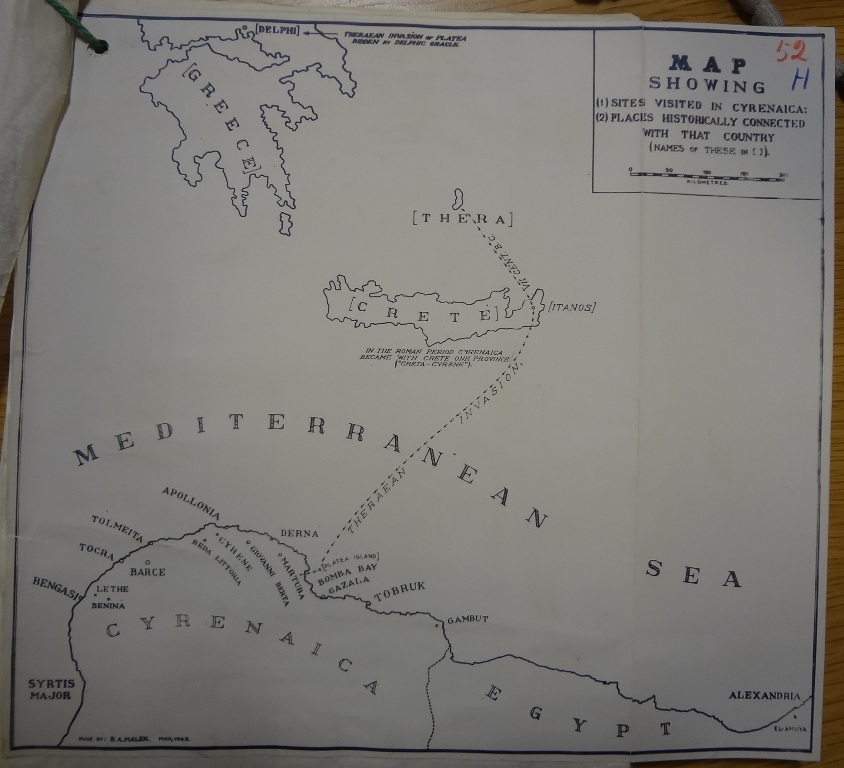

In 1943, Lieutenant-Colonel Mortimer Wheeler was in Libya with the Eighth Army and wrote that it was ‘urgent’ to ‘put the War Office to work’. He was not complaining about the military campaign in North Africa. Wheeler was the Keeper of the London Museum and the Director of the Institute of Archaeology. The war was important to him, but the state of ancient monuments even more so (WO 32/10157).

On his advice, Second-Lieutenant Ward-Perkins, once his assistant at the London Museum, was seconded from regimental duty to take over the protection of the ancient monuments in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, in the north of Libya. This area was occupied by the Allies, who had evicted the Italians in late 1942 (WO 208/2818).

The protection of archaeological sites and antiquities had always been on the mind of British military personnel, but in Libya their reputation was also at stake.

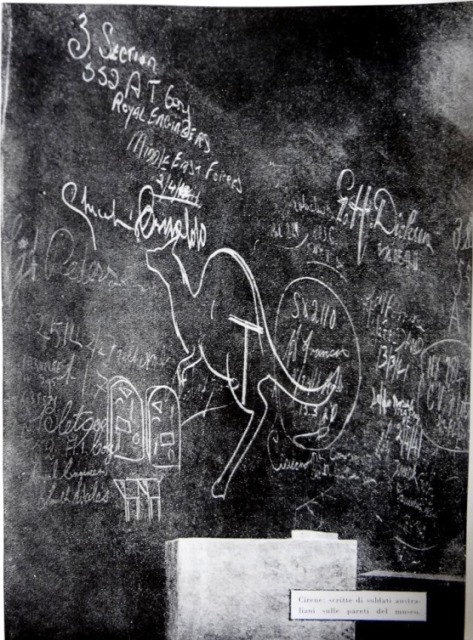

Frederick Kenyon, of the British Academy, thought it was necessary to publicise British interest in archaeology ‘to forestall enemy slander’. After General Wavell’s retreat from Cyrenaica in 1941, the Italians had made ‘great propaganda use of the damage done to their ancient monuments’ (WO 32/10157). In fact, they had even published a pamphlet ‘in which they purported to enumerate the acts of vandalism perpetrated by [British] troops during our three months’ occupation of the territory’. Under the very clear title ‘What the British have done in Cyrenaica, 1941’, the pamphlet listed all sorts of degradations, from graffiti on the walls to the destruction of statues, especially in Cyrene, an ancient Greek and Roman city (FO 141/963).

Alleged Australian graffiti in Cyrene (catalogue reference: FO 141/963)

In May and August 1943, Alan Rowe, the Egyptian Antiquities Service’s Inspector of the Prohibited Military Area, Western Desert, and Conservator of the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, was sent on a mission to report ‘what, if any, damage [had] been done in the course of the war’. He stated: ‘the falsity of this propaganda is clearly obvious, and it has given us much pleasure to be able to refute it’.

Judging from the numerous photographs illustrating his report, it is likely that before the first British occupation, in the winter of 1940-1941, the Italians removed some monuments stored in Cyrene and sent them to Tripoli; when they returned, they photographed the empty magazines for propaganda purposes.

While he wasn’t endorsing the desecration of ancient monuments and antiquities, Rowe argued that the rooms had been empty when the inscriptions had been scratched on the walls; that the walls were modern ones, not antiquities; and that some of the graffiti may be fakes as some of the names seemed very Italian and Germanic to him. He concluded:

‘the Italians are not entitled to make a great fuss about the inscriptions, more especially as they themselves left coloured vignettes on the walls of rooms 1 and 2 of the Epigraphical-Archaeological magazine’ (FO 141/963).

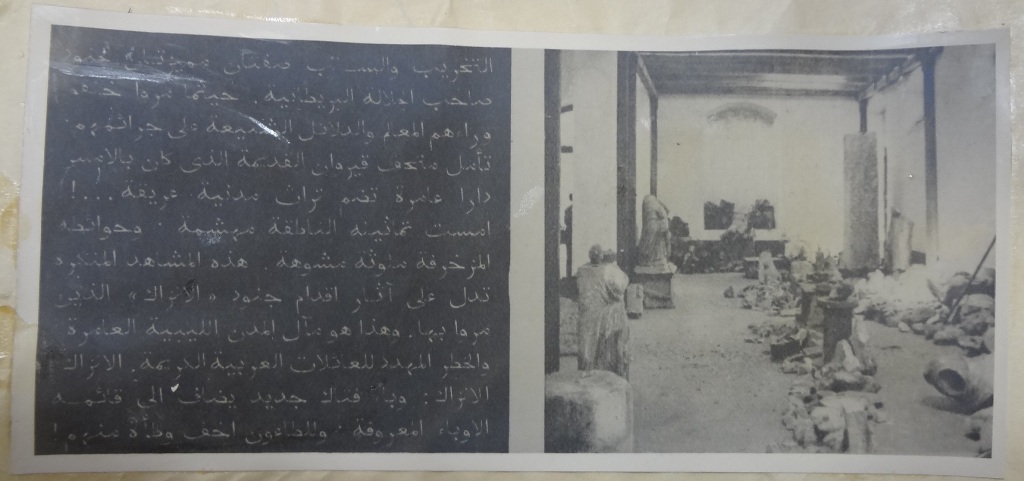

Another pamphlet, written in Arabic and entitled ‘England, the serious enemy of Islam’, warned that left in the hands of the British, Libyan archaeological sites would very probably be destroyed. The author blamed the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs), stating: ‘the ANZACs are a new deadly disease to be added to the list of other famous diseases. Pest is less dangerous than them’ (FO 141/963).

‘England, the serious enemy of Islam’ (catalogue reference: FO 141/963).

After these (slanderous) accusations, the conclusion of Rowe’s report was rather reassuring:

‘practically no wilful damage at all has been done by the soldiers of the [British and Imperial] armies to the remains of Cyrenaica. Therefore the honour of our armies still stands high in this as in all other respects.’

To be on the safe side, he recommended that ‘strict orders should be published’ to safeguard the monuments, and commented: ‘rumours have reached our ears that a small amount of “digging” is going on in this area’ (FO 141/963).

Rowe visited Tocra (the ancient Teuchira and Arsinoe) in May 1943. The Italians had just started excavating when the war broke out, and both Rowe and Ward-Perkins had scathing comments to make. ‘Excavation has consisted solely of clearance,’ Ward-Perkins complained 1; he conceded, however, that ‘the stratigraphic relations [could] probably still be determined’ (FO 1015/107). Rowe was more direct and stated: ‘the Italians are better philologists than archaeologists’ (FO 141/963).

Alan Wace, Professor of Classical Archaeology at Cambridge, also visited the site in August 1943. He noted that all records and photographs, along with some antiquities, had been evacuated to Tripoli by the Italians in 1941, but that ‘the tombs in the quarries to the East [hadn’t] all been plundered’. He still thought that excavating ‘wasn’t practical’ (FO 1015/107).

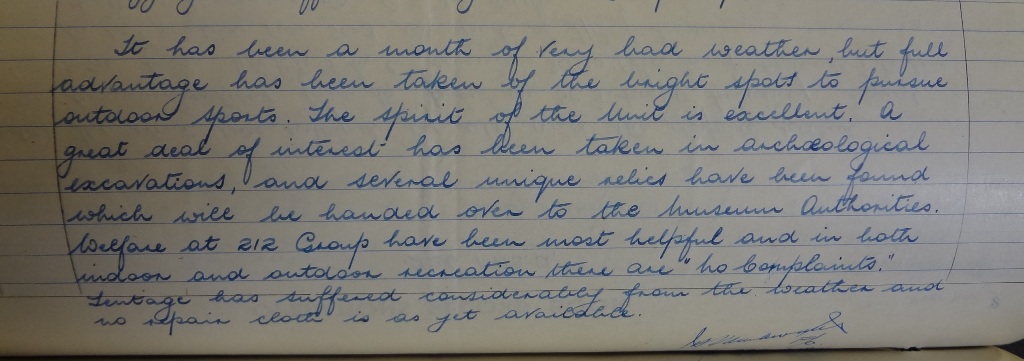

On 29 February 1944 Flight-Lieutenant Winkworth, of the 226 Mobile Signals Unit stationed in Tocra, wrote in the summary of events: ‘a great deal of interest has been taken in archaeological excavations, and several unique relics have been found, which will be handed over to the museum authorities’ (AIR 29/150).

Summary of events, 226 Mobile Signals Unit (catalogue reference: AIR 29/150)

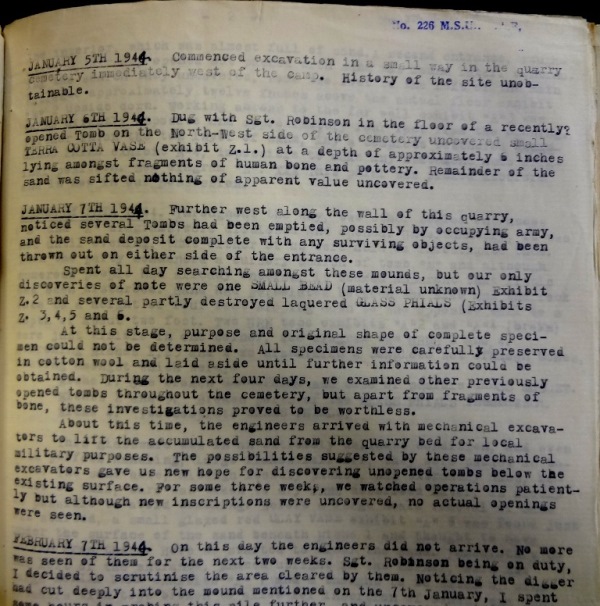

First page of Sgt Webster’s excavation diary (catalogue reference: AIR 29/150)

Although formal approval was only granted in March 1944 (WO 230/166), Sergeant Webster had started excavating the Eastern Quarry Cemetery in January. Major Tackrah, the Legal Adviser at the headquarters of the British Military Administration in Cyrenaica, later described Webster as ‘an ardent archaeologist’, and it is true that his excavation diary, complete with diagrams and photographs, has a very professional feel (AIR 29/150).

Along with other RAF personnel, Webster started looking through tombs in the necropolis, and took advantage of ongoing engineering work to look for new ones under the existing surface.

Inevitably, the war got in the way; ‘duty prevented us from carrying on with the search,’ he deplored on 26 February. He still found time to clear several tombs very methodically.

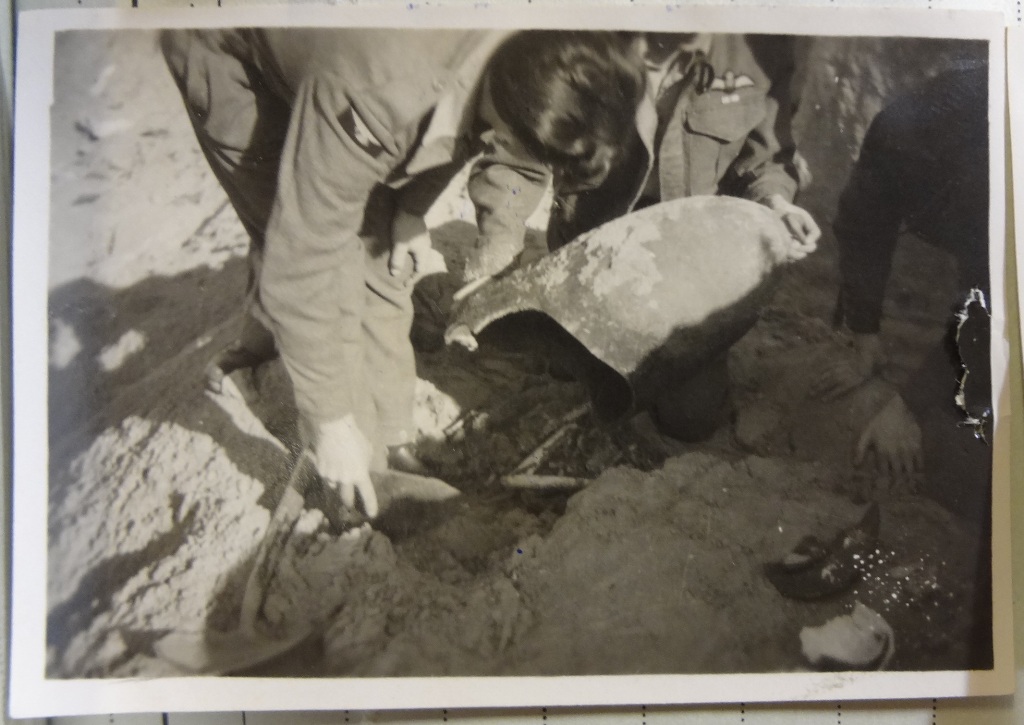

At work in Tomb B (catalogue reference: AIR 29/150)

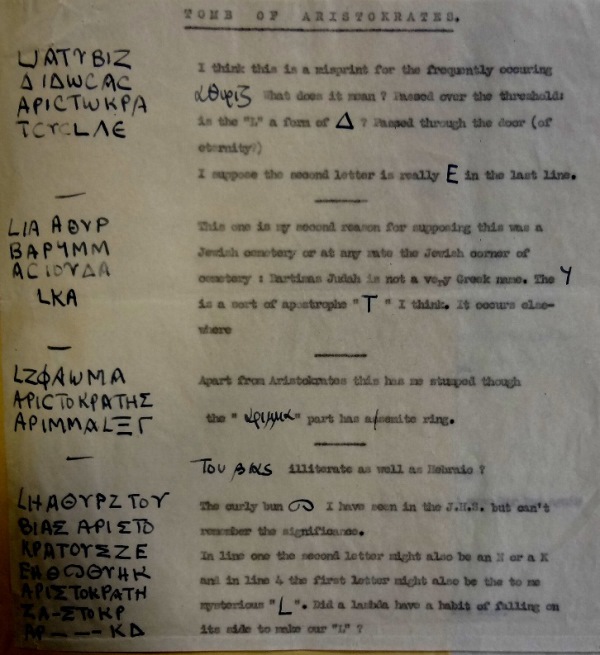

Inscriptions copied by Major Tackrah in Tocra (catalogue reference: AIR 29/150)

Between March and June 1944, Webster’s work at Tocra attracted a lot of visitors eager to examine the site, the finds, and the diary.

Major Tackrah copied the inscriptions uncovered, translated them to the best of his abilities, and sent everything to his cousin Harold Idris Bell, the Keeper of the Department of Manuscripts at the British Museum, for a second opinion. He wrote: ‘the inscriptions are very crudely cut, and there is a general air of poverty and I gather illiteracy about the whole place’ (AIR 29/150).

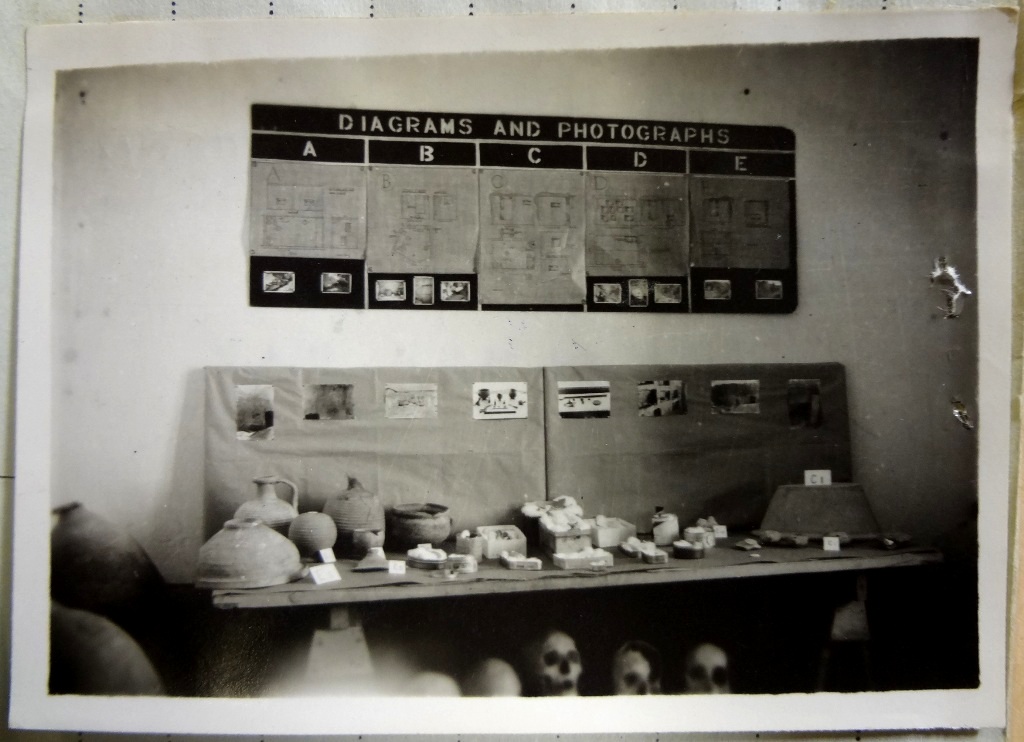

In May 1944, it was decided to set up a small museum in the old Italian clinic, the ambulatorio, to showcase the findings. Major Hyslop, the Monuments and Fine Arts Officer for Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, noted in October 1944 that the collection was ‘displayed in the most admirable way’ and that it contained ‘all records of the work’.

At the end of 1944, military operations got in the way of archaeology again, and a new home for the museum was suddenly required as the medical services needed the ambulatorio. Hyslop considered using a butcher’s shop across the road, but it turned out to be unavailable. He noted in his report:

‘it would be the greatest pity if this small museum, so well arranged by Sgt Webster of the R.A.F, had to be given up and it is hoped that the medical authorities can wait till an alternative is found or constructed’ (WO 230/166).

The Museum in the Tocra Ambulatorio (catalogue reference: AIR 29/150)

Hyslop devoted a lot of time and energy to publicising Libyan archaeological sites. Along with Sergeant Applebaum, he compiled a guide book on Cyrene, organised tours, visits and lectures. They even set up an exhibition in the Castello in Tripoli, which proved very popular. By June 1945, 200 to 250 people visited the sites each month (WO 230/165).

Exhibition at the Tripoli Castello (catalogue reference: WO 32/10157)

During one of his lectures, delivered at Derna in April 1945, Sergeant Applebaum thought it wouldn’t hurt to remind his audience a few basic facts; ‘a word on archaeology as a science,’ he said, ‘it is a science, and not just a hobby of cranks or the wealthy’. He was, of course, quite right. He was also right to state that archaeology ‘aims at enlarging man’s self-knowledge and reconstructing history’ (WO 230/166).

Mortimer Wheeler was horrified that mere amateurs could dabble in archaeology. But with such a great goal in mind, could he really blame British soldiers for having indulged in ‘a small amount of digging’?

Notes:

- 1. ‘Memorandum on the Antiquities of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica and on the future of archaeological research in these two countries’ ↩

[…] http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/archaeology-libya-second-world-war/ […]

Thank you for this important information

I spent 6 months in Libya in 1979 and visited the site of Cyrene (I recall that Mortimer Wheeler was in charge of the excavations there). The scale and magnificence of the site was breathtaking. Sadly a revisit is hardly on the cards at the moment.

It was fascinating to read about Tocra. My late father, Philip Horobin, was a member of the 226 MSU and took part in the excavations at Tocra with Sgt Webster. He passed on to me, shortly before his death, his records of the excavations. These include his own hand-drawn map of the site, his own photo album recording the excavations (the finds, the digging, and the museum), and a carbon copy of Sgt Webster’s diary. My father told me that it was agreed by the small team that he would be the main record-keeper of the excavations as he was considered suitably organised. I would be happy to share these documents.