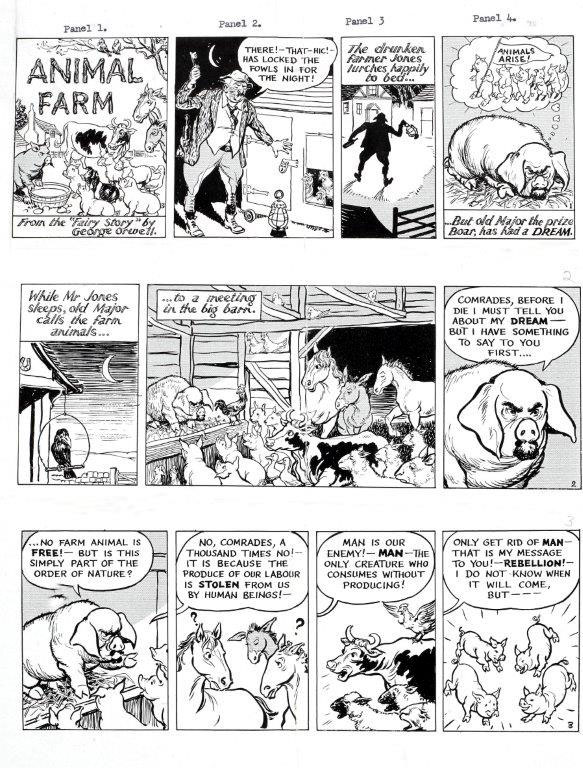

George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’, first published on this day 75 years ago in 1945, is a work familiar to many. The fable (or ‘fairy story’ as Orwell described it) of a gang of animals who take over their farm, overthrowing the cruel Farmer Jones, only to end up in an even more brutal state of slavery under the new regime, is a standard part of the school curriculum. As a satire on Soviet Communism, it is famous. The story of ‘Animal Farm’ gained even wider currency through an animated film version in 1954 by Halas and Bachelor.

‘A most effective propaganda weapon’

But did you know that, before the film materialised, a cartoon strip version had been created? This was at the instigation of the Information Research Department (IRD), a department of the Foreign Office set up to counter Soviet propaganda. The IRD bought the strip cartoon rights in late 1950[ref]Orwell had died on 21 January 1950. The Orwell Estate continued to look after his literary legacy.[/ref]. The IRD clearly recognised the value of Orwell’s story: from their perspective, it was a powerful instrument in the Cold War: ‘this work has been translated into many languages, and has proved to be not only a best seller, but also a most effective propaganda weapon, because of its skilful combination of simplicity, subtlety and humour’[ref]IRD Circular, 11 Dec 1950, Catalogue ref: FO 1110/365.[/ref]. The IRD contacted the international network of Information Officers to encourage them to secure publication of the cartoon strip in a newspaper in their territory.

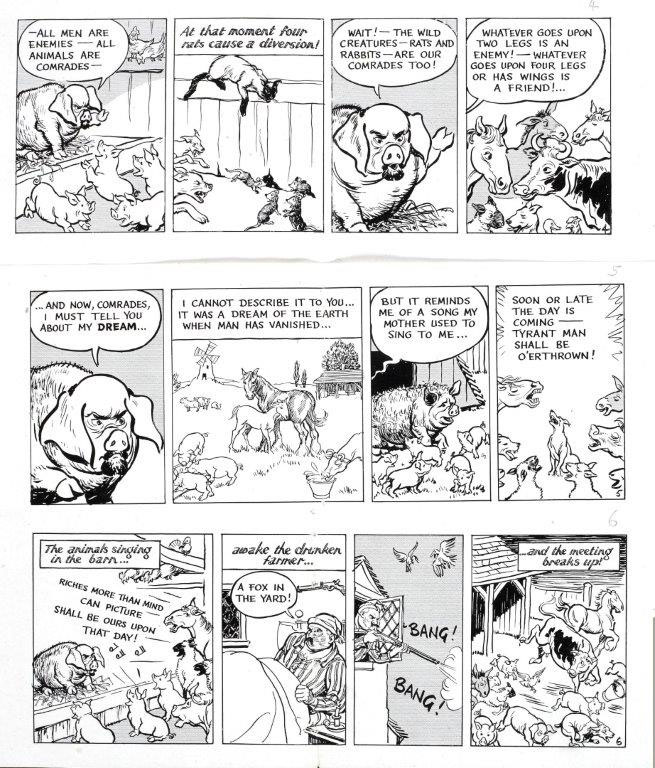

The plan was to tell the story ‘in approximately 78 cartoons, each cartoon containing three or four panels. Thus, if the feature were run by a daily paper, it would take about 13 weeks to tell the whole story’[ref]ibid.[/ref].

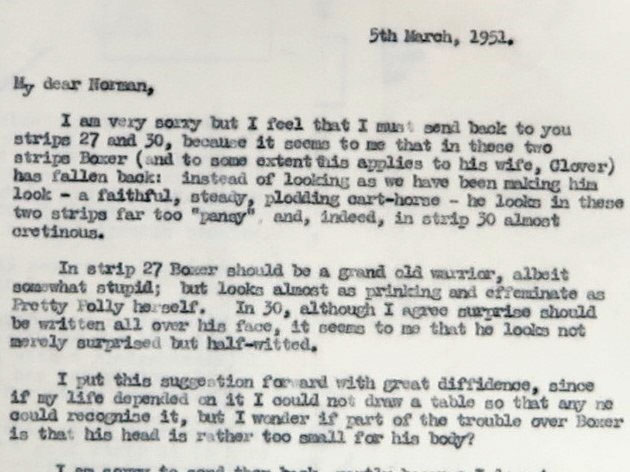

One of our files[ref]FO 1110/392[/ref] contains some very interesting correspondence which is illuminating about the production process for the strip cartoon. It is correspondence between Mr Lt. Col. Leslie Sheridan of the IRD, Don Freeman, an artist who lived in East Grinstead who provided the ‘roughs’ of the drawings, and the cartoonist Norman Pett who lived in Crawley (who produced the final versions of the cartoons). The correspondence between them is very friendly – both Don and Norman address Leslie Sheridan as ‘Sherry’ (as I shall now refer to him), and they all regularly meet for lunch at the ‘Press Club’ – but sometimes, of course, alterations to the work are called for and Sherry has to deliver constructive criticism (and sometimes apply some pressure regarding deadlines).

The challenge of condensing

If you think about it, the process of condensing a novel – even a relatively short work such as ‘Animal Farm’ – is a real challenge. Inevitably a few changes have to be made – in Don Freeman’s words, ‘I have taken a few liberties’, though he felt they were ‘in the spirit of the book’. As Don explained to Sherry: ‘my difficulty all along has been the tightly-packed “meatiness” of the story’ – the incidents are closely linked and if you cut one, it may affect some other development in the story.

Difficulties emerge regarding the depiction of Boxer, the great cart-horse, who is the model worker, incredibly hard-working and compliant, symbolising the Stakhanovite movement in the Soviet Union. Sherry made forthright criticisms of early depictions of Boxer, using some language which would now be regarded as politically incorrect. Referring to the latest strips he has received, he writes that Boxer looks ‘far too “pansy” and, indeed, in strip 30 almost cretinous’. He goes on to describe Boxer as looking ‘prinking’, ‘effeminate’ and ‘half-witted’.

Norman replied to these comments, agreeing to work on the returned cartoon strips but disagreeing that Boxer had too small a head, and adding ‘it is still difficult to get the simple expression, without making him half-witted’. Sherry further explained: ‘I am very sorry to be such a nuisance over Boxer, but it is important because he is a key character; and I think it is vital for the story to get the contrast between Boxer –simple, honest and faithful, and Ben, the donkey – cynical and ironical, and worldly wise’. It was a very challenging task for Norman but he succeeded in the end – Sherry was delighted with the revised strips.

Regarding the extracts reproduced in this blog post, I’m sure that you would agree with my verdict that they are of a very high standard in terms of the graphics and the easy to follow script. Interestingly, ‘Old Major’, described in the book as ‘the prize Middle White boar’, has features in these early scenes which make him reminiscent of Lenin. Later on in the story Napoleon, ‘a large fierce-looking Berkshire boar’, emerges as the dominant animal figure, who was clearly based on Stalin, and presumably this was reflected in the cartoon strips.

By April 1951, with the cartoon strips completed, the IRD contacted their network of Information Officers across the world, from Asmara (Eritrea) to Tokyo, encouraging them to do all they could to secure publication in a newspaper in their territory, and this endeavour met with a good measure of success, judging from reports in FO 1110/392.

Local adaptations

Translations were necessary, of course, and the IRD became aware that the setting of ‘Animal Farm’ was thoroughly ‘English’ and that, for their purposes, this was a disadvantage. When considering a further cartoon strip project, ‘Greenhorn’s Travels’ in ‘Stalinovia’ (also referred to as ‘Gullible’s travels’), the IRD suggested that local artists could have a role to play in adapting the cartoons to meet the needs of the locality. Mr Tull at the Foreign Office, in a letter of 13 August 1951 to James Murray, British Embassy, Cairo, wrote: ‘we could have the cartoons drawn in London and sent to you in the hope that you could get a local artist to convert oak trees into palm trees, bowler hats into fezzes, skirts into sarongs, etc’. The alternative suggestion was follow a script and ‘have the strip drawn locally by your own artist’.

The IRD were keen to know what the impact was of the ‘Animal Farm’ strips on readers and asked questions of the Information Officers such as ‘has it been appreciated that this is a subtle piece of anti-Communist propaganda? Has it aroused any resentment among Communists? Has it given amusement to the readers?’ Disappointingly, however, there are no direct responses from the Information Officers to these questions on the file, just hints that the ‘Animal Farm’ cartoon strip had been a success – for example, it is reported that the cartoon was well received in Asmara ‘giving food for thought and discussion to the local population’, and it had led to increased sales of the ‘El Heraldo’ newspaper in Caracas.

A fascinating post shedding yet more light that on a book many studied as part of English literature.

Orwell laid bare Tyranny: after him, we all knew it was about Power pure and absolute. Will someone now emerge to strip bare the aims behind ‘woke? the New Fascism?

Thank you Richard, am glad you enjoyed it

It was 1961 and I was a 10 year old in primary school. Our headteacher told us to get our jotters out and start colouring in page 11, a world map.

She said, “If the school inspector arrives we’re doing geography. But actually I’m going to read a marvellous book to you.”

Yes, it was Animal Farm and I have never forgotten the thrill of listening to something we shouldn’t be listening to and learning a bit about how society works.

I must admit that I did not read this book until my children had it at school. I could not have described communism better to them if I had tried. Bought my grandchildren a copy. They all enjoyed it and said it taught them so much.

Fabulous. Wonderful. Really love this. Many thanks.

Please can we have one for South African readers? I am sure the Maverick or better still the Institute for Race releations could run the strip version. We have plenty of illustrators who could modify it.

Hello Mark,

Are you aware of the fact that not only Norman Pett created a cartoon strip version?

While the team at Halas and Bachelor was working on the animated film version the artist Harold Whitaker -key designer with that firm- created his own strip version. Of course this strip was in the mould of the animated film.

Searching for ‘Harold Whitaker Animal Farm’ on Google will give some examples of his artwork and additional information.

Kind regards from The Netherlands,

John Wigmans

Thanks John for this useful information, I was interested to check it out

The Halas and Batchelor film was financed by the CIA, for whom future Watergate convict Howard Hunt was in charge of the operation. Notoriously the film changes Orwell’s ending to avoid his implication that communism and capitalism were two sides of the same coin. In the novel the pigs are shown as becoming indistinguishable from the humans they had overthrown; whereas the film’s ending is a straightforwardly negative portrayal of the pigs (i.e. the communists), whose rule is overthrown by counter-revolutionary animals.

Leslie Sheridan, who was in charge of the earlier IRD operation to produce an Animal Farm cartoon strip, had been a wartime propagandist with SOE and even earlier with Section D.

In 1962 Sheridan and Hans Welser, a Swiss immigrant whom he had recruited to Britain’s propaganda services, swapped wives, with Welser marrying Sheridan’s ex-wife Adelaide, herself an SOE/PWE/MI6/IRD veteran.

Adelaide Welser retired from IRD in 1970, but Hans seems to have been working until a year or two before IRD’s closure in 1977. During the early 1970s Hans Welser was much involved with efforts to discredit British historian David Irving, partly related to the latter’s involvement with the late Rolf Hochhuth in researching controversial theories about the death of wartime Polish leader Gen. Władysław Sikorski.

It seems a booklet version ofthe strip cartoon was sold by the Times or The Times Literary Supplement in the early 19970s.

Could anyone provide information on this publication ?