Last week, some of us from The National Archives were privileged to spend a day in Cambridge with over 50 people from the heritage spheres gathered for the Digital Preservation Coalition event, Links that Last.

(For those new to the concept of linked data, I have no hesitation in recommending this Wikipedia article: ‘linked data describes a method of publishing structured data so that it can be interlinked and become more useful. It builds upon standard Web technologies such as HTTP and URIs but rather than using them to serve web pages for human readers, it extends them to share information in a way that can be read automatically by computers.’)

As the Links that Last programme puts it:

‘The emerging ‘Linked Data’ approach … challenges us to think about preservation in new ways. Simultaneously, the digital preservation community has put considerable effort into the development of persistent identifiers, services that seek to ensure that essential links are not lost and … that the highly distributed contexts in which information is presented are protected against the vagaries of time and obsolescence’.

We have been thinking for sometime about the nature of the challenge that government’s use of semantically linked data would create for our remit to capture the record. With a government website, we capture that website, but not everything that website links to, and we capture different websites at different times from each other. The UK Government Web Archive (UKGWA) isn’t an exact replica live government web estate, nonetheless, as a provider of referenced archival copies, it works very well. But linked data could link to anything: is there any way you could meaningfully capture a bit of it? would it make sense in the way the web archive does? and what is it that we need to capture?

The advice for those creating linked data is to use persistent identifiers. Persistence implies it will hang around there in the ether, but for how long? Will persistent identifiers be overwritten with the latest version, or will the older versions persist alongside?

Over time, will the web of linked data start to look a moth-eaten cardigan; the knitting still linked but full of holes? However, a cardigan has a definable shape (even the iconic cardigan as worn by the archivist), but the web of linked data seems more like an infinite piece of knitting.

We are used to broken links on the web of documents, the UKGWA effectively darns over a hole and take us to an archived version of a page. Would the equivalent of that in the linked data world be possible, or even required? Humans tend to see a new technology through the prism of an existing one; the first feature films were statically filmed stage plays and, when the web first came along, people worried how users would find their way to web pages, and BBC announcers painstakingly read out URLs: ‘Double u double u double u dot ‘. Back in the day, how could you imagine Google?

I went to Cambridge with such thoughts in my head, hoping for answers.

One of the problems with linked data is that for the end user, us, it is very difficult to see it. It’s viewed through a web browser and seems to act like a clever web page, its particular properties hidden away. Southampton’s Open Linked Data site, showcased by Chris Gutteridge, is designed to be of practical up to date use for staff and students. I had a personal interest as one of my sons was recently a student at Southampton – did the builders of linked data imagine it as a parental resource? Did he put ‘cake’ in the catering page, and by the miracle of linked data track down a slice to the café in the library:

Catering APP: Linked data 'Cake'

– which works as a building like this?

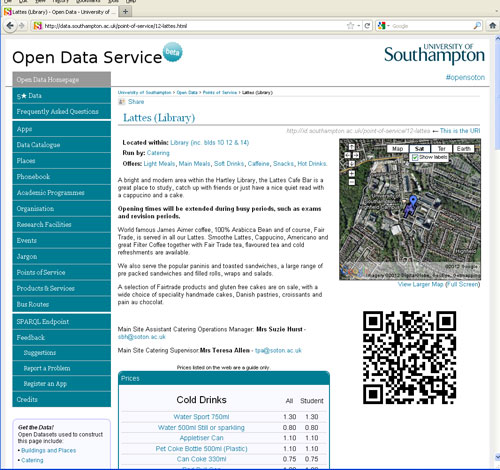

Linking Lattes in the Library Building

Chris spoke about some of the difficulties he encountered in setting up Southampton’s linked data. One example was the campus’ re-use of building numbers to prevent them being more than two digits long. Over time, this meant that building number 10 could refer to several different buildings – an identifier neither persistent or unique. However, in the linked open data, there was enough context around the building from other links to indicate which was referred to. Chris’ remark that resonated with me most was also picked up by those who were tweeting from Cambridge: ‘there will be no best practice in identifiers, do what works for you and don’t expect others to do the same.’ #dpc_links

Archivists have always had to contend with records being what they are – imperfect, wrong even. It is our job to capture those imperfections. And we have been dealing with persistent unique identifiers ever since we, and librarians and museum curators, decided it would be a good idea to distinguish one item in our collections from another.

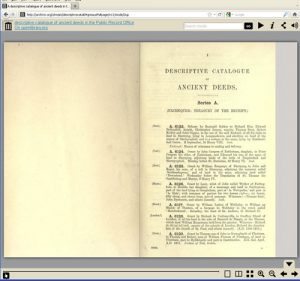

Whilst superficially Googling to see if I could find an example of an ancient persistent identifier, from say, the Library of Alexandria, I instead came across some rather old identifiers from our very own collection:

They certainly persisted, as here we are able to read them – in a cool page turning app to boot – but what do they mean? and how do they help us today?

They were meant to provide the answer to a problem of indexing, in the days long before the online whizzy search features of our new catalogue, Discovery. This online version of the deeds being volume IV, divorced on the web from Volume I – which presumably had an explanation, or contextual metadata as we might call it, as to what these deeds actually were. So, persisting, but not altogether identifying.

I’m no medievalist, but guessed the ancient deeds were going to be amongst Exchequer records, but which? Resisting the temptation to rush downstairs to our Archive and Records Knowledge team, requesting the immediate assistance of a medieval records expert, I spent a while on Discovery (modern technology to the rescue) and eventually identified them and their chequered history as Exchequer series E 40:

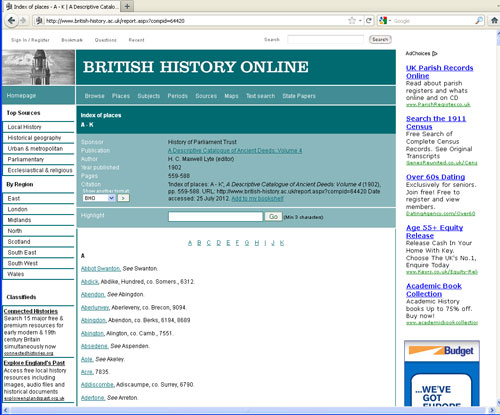

The catalogue identifiers, although they index the deeds, are not a lot of help in finding the rich place and person data scattered in these ancient deeds. The Institute of Historical Research’s British History Online site shows how it can be done:

British History Online version of Ancient Deeds with links to place names

Back at Links that Last, we had sessions on how linked data could improve the persistent identifiers; and how linked data itself could do amazing things to enrich archived and library material, but no one spoke on how you archive semantically linked data. Thirty years ago we had no idea how to archive conventional unlinked data, data that was crunched through huge government computers, the sort of data that now turns up in an Excel spreadsheet. It was seriously suggested that maybe we should archive the unwieldy green fan-fold printouts that tabulated the results of the number crunching, or maybe we should take the dinner plate sized magnetic tapes, that held the actual data, but needed a large computer of the same make to process it. Both suggestions were eventually rejected. Now we have progressed, through the pioneering and highly successful National Digital Archive of Datasets, to scooping up gigabytes of government data through the Web Archive on a daily basis.

We are probably at the green fan-fold stage of linked data – we could capture its products, but not what it does, nor do we know if the moth-eaten cardigan analogy is relevant. Identifiers will persist and government and technology will move on. And The National Archives will, as ever, be taking up the challenge.

We would very much like to hear from anyone who is out there working in this new field of endeavour. Do please get in touch.

Hi Linda,

I really enjoyed your blog post. I don’t really know where to begin on archiving this stuff yet, there’s so much context surrounding the linked data infrastructure that needs maintaining I feel it’s quite a challenge. One of the thoughts that I’ve had consistently from the beginning though is that it would help dramatically if all linked datasets included temporal information by way of quads, and that, as part of the persistence being called for, users are always able to amend URIs to see data at a specific point in time as well as the most recent data. I believe quite heavily in the importance of maintaining a stream of consciousness for all modern datasets published this way. I think that archiving would then become a lot more intuitive.

I’m interested in your thoughts, and what other Linked Data users think of archiving *their* world!

Ross

Ross,

Like the timestamp idea; a kind of Memento solution http://arxiv.org/abs/0911.1112/ , but for linked data rather than archived web pages?

A couple of projects you might find of interest if you don’t already know them.

There was some research done at the University of Southampton to preserve linked data by ensuring Link integrity, via either prevention and maintenance, or recovery http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/270897/1/ldow2010_paper08.pdf

And more recently the ongoing ‘Wf4Ever’ project http://repo.wf4ever-project.org/dlibra/docmetadata?id=28 aims to preserve linked data research object workflows in the scientific community. Encouragingly makes the point that preservation requires a guarantee of the content and state of the research object beyond that of merely publishing it.

Linda