Our Research Exchange series features the work of researchers across The National Archives in which they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open it up to new ideas and discussion.

This month and next, to coincide with our upcoming Annual Digital Lecture, we will be publishing a series of blogs focusing on different aspects of digital research happening at The National Archives.

Our staff will be writing and reflecting on their research, discussing topics such as using AI in archives, using 3D Virtual Tech to access heritage collections, archiving citizen research projects, and much more.

In this blog, Dr Katherine Howells discusses the way data can be cleaned and analysed to reveal important historical information.

Katherine writes …

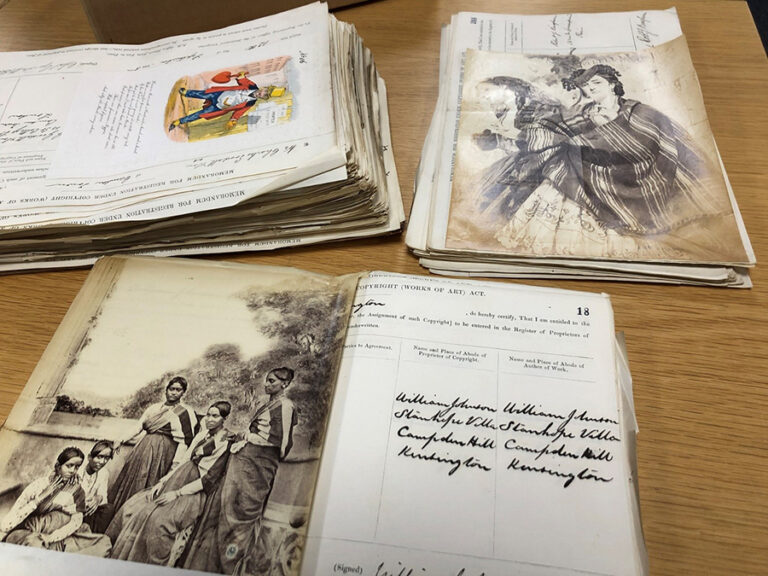

In the 1860s photography as a new medium was coming under scrutiny and issues of ownership and copyright were being debated. This culminated in the 1862 Fine Arts Copyright Act, which allowed people to register photographs, paintings, and drawings with the Stationers’ Company for copyright protection for the first time. These records are now held at The National Archives in record series COPY 1.

This blog explores how the rich catalogue data for this collection can be cleaned and analysed in order to reveal how photographers and publishers responded to the new legislation and uncover information about the nature of photographic industries in the early 1860s.

To register a work for copyright protection, an individual or company had to complete a form, giving a description and the names and addresses of the copyright owner and the author (the photographer or artist) and attaching an example of the image being registered. The detail from these forms now make up the COPY 1 catalogue data, having been carefully transcribed by volunteers over several years. See our blog on Cataloguing and analysing 19th-century artwork to learn more about the next stage of this volunteer cataloguing project.

Cleaning the data

The catalogue data posed significant problems for analysis and required careful cleaning. The details transcribed from the entry forms appear as a single text field, so to enable any analysis, this information needed to be separated out into individual fields.

First, I downloaded the data from The National Archives’ catalogue and created a dataframe in Python using the Pandas library. Then I used regular expressions to separate out the description from the names and addresses of the copyright owner and authors, based on the structure of the text in the field. This left me with columns for ‘description’, ‘name of copyright owner’, ‘address of copyright owner’, ‘name of copyright author’, ‘address of copyright author’ and ‘notes’ for additional information included in the original field.

I then categorised the data based on several criteria: whether the work appeared to be a photograph or an artwork; whether the entry form continued multiple works; whether the owner and author were identical; and whether there was or was not a copy of the work attached to the form.

Copyright trends

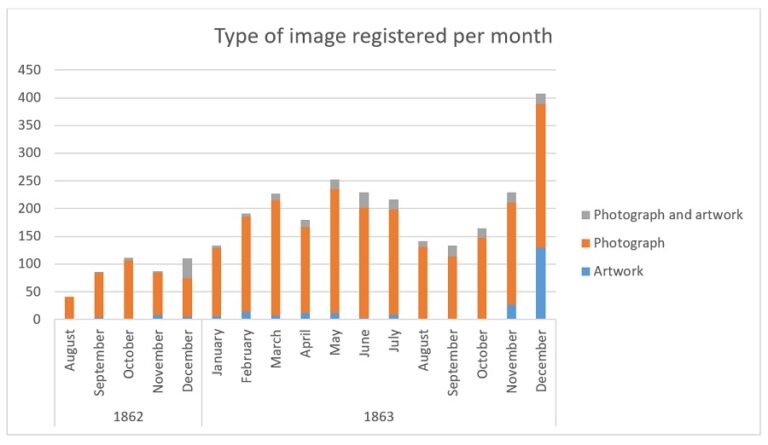

Photographers, artists and publishers responded gradually to the new registration system, submitting on average 88 forms per month in 1862. This rose to on average over 200 a month in 1863, perhaps a result of the growth of photographic industries, but also perhaps increasing awareness of and engagement with the legislation. There is a particular spike in December 1863 with over 400 registrations.

Even though the legislation covered paintings and drawings as well as photographs, photographs made up the bulk of the works registered in the first 17 months. Over 80% of the images registered were photographs, although there was a slight increase in the appearance of other forms of artwork in November and December 1863.

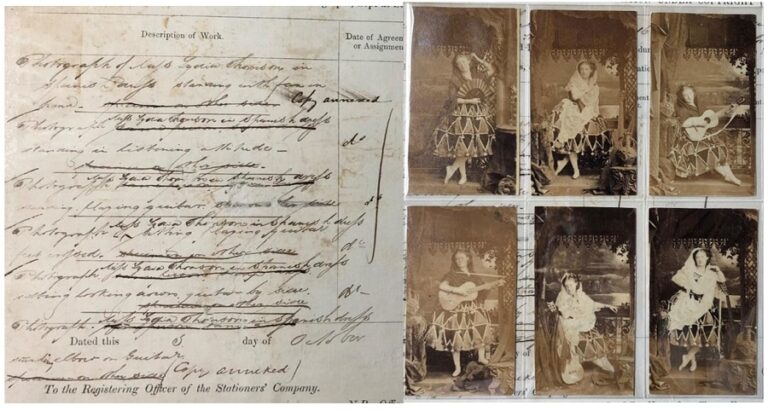

More than 20% of the forms submitted were registering multiple images with one form. In the entry form COPY 1/1/139, William Henry, Frederick and Edwin Southwell, London-based portrait photographers trading as the ‘Southwell Brothers’, list six photographs of dancer, actress and comedian Lydia Thomson in the description box.

However, it was very common for forms to be submitted with no image attached. Paintings and drawings are far more likely to have images attached than photographs. Over 90% of forms registering paintings and drawings have images attached, while it’s just over 50% for photographs.

Photographic and artistic networks

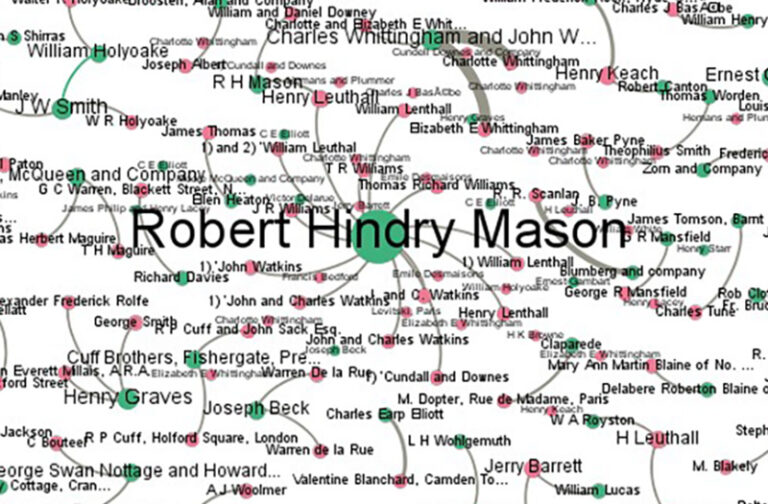

The presence of details about both the copyright owner and the author in the data allowed for the study of photographic networks in the period. I adapted the data to produce a network graph showing the connections between owners and authors in each registration they made.

One initial finding of this analysis is that over 80% of forms included the same person as both copyright owner and copyright author. This indicates that at this time, the majority were registering their own work for copyright protection. This is far more common for photographers than for artists.

This does support the idea that the ‘gentleman amateur’ was a significant presence in British photography in the early 1860s. Self-registrations for paintings and drawings were far less common, suggesting that artists would more often be commissioned by a printer or publisher.

London photographer Robert Hindry Mason, known for his portraits of Charles Dickens, is particularly active in the graph, having submitted 28 forms registering multiple photographs. The graph reveals he worked with several other photographs to register works, including successful portrait photographers John and Charles Watkins and stereoscopic specialist Thomas Richard Williams.

Overall, it is evident that at this early stage photographic networks were fairly small and disconnected. Most photographers were registering their own works for themselves, or working with just one or two others.

While it is important to bear in mind the limitations of this analysis, this initial study does show the great potential of using digital methods of analysis to interrogate archival data. This kind of analysis opens up excellent opportunities for studying industries and networks which can be hard to uncover in other ways. I hope to extend this analysis to a larger dataset of COPY 1 records in the future.