According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a diplomat is ‘a person who can deal with others in a sensitive and tactful way’. But what happens when they don’t? In the 1920s in Cairo, the British Residency had many a problem with Dr Morton Howell, the American Minister – some amusing, others with more serious political consequences.

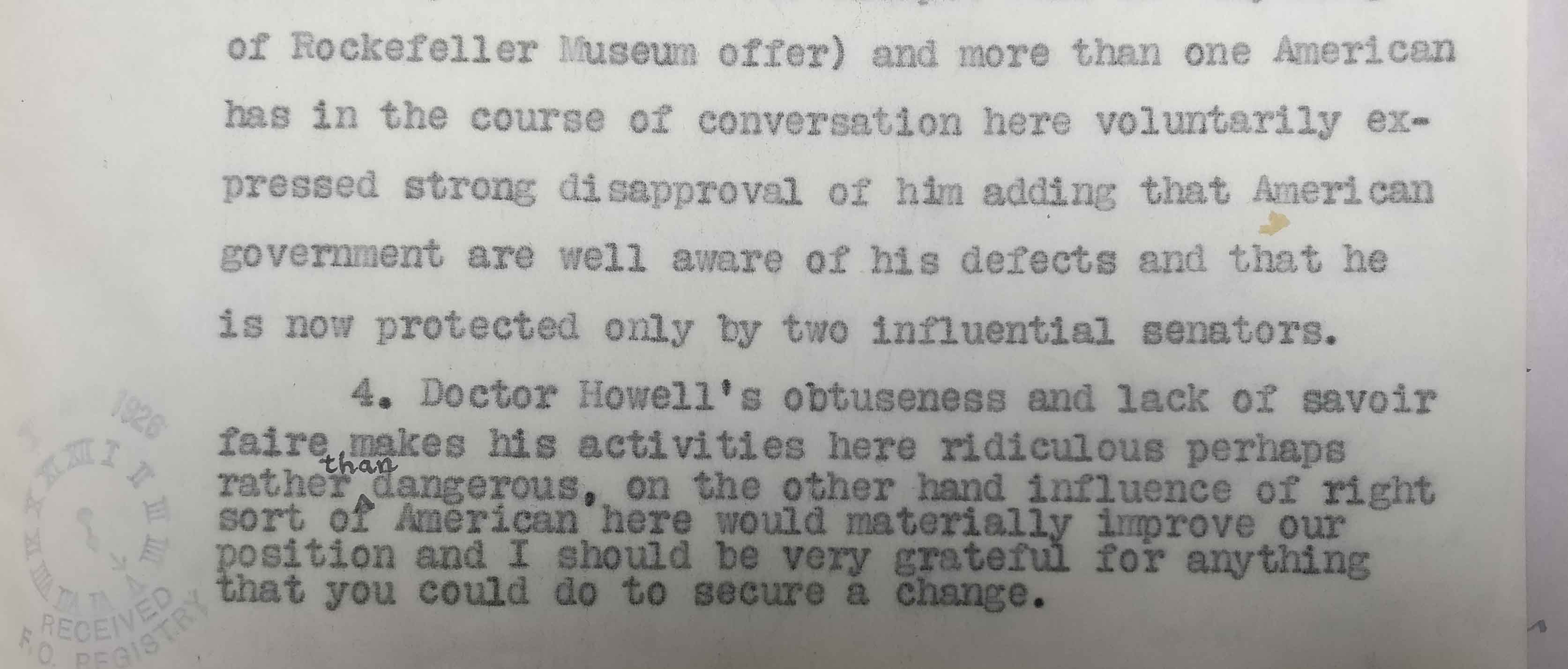

On 1 March 1926, George Lloyd, the British High Commissioner in Cairo, asked the Foreign Office to make representations to Washington and to secure Howell’s removal from Egypt – a request he would subsequently make numerous times. The American Minister, he reported, had called on Egyptian nationalists and was spreading anti-British propaganda. ‘Dr Howell’s obtuseness and lack of savoir faire makes his activities here ridiculous perhaps rather than dangerous,’ he wrote, adding that he would still ‘be very grateful for anything that [the Foreign Office] could do to secure a change’ (FO 371/11608).

The Foreign Office thought it would be difficult to make representations to the Americans. Howell had ‘clearly been both stupid and tiresome’, but it wasn’t quite enough. Besides, if, as the High Commissioner seemed to think, Howell was not on the best of terms with the State Department and unpopular among the Americans in Cairo, it might be easier to let Washington deal with their own representative.

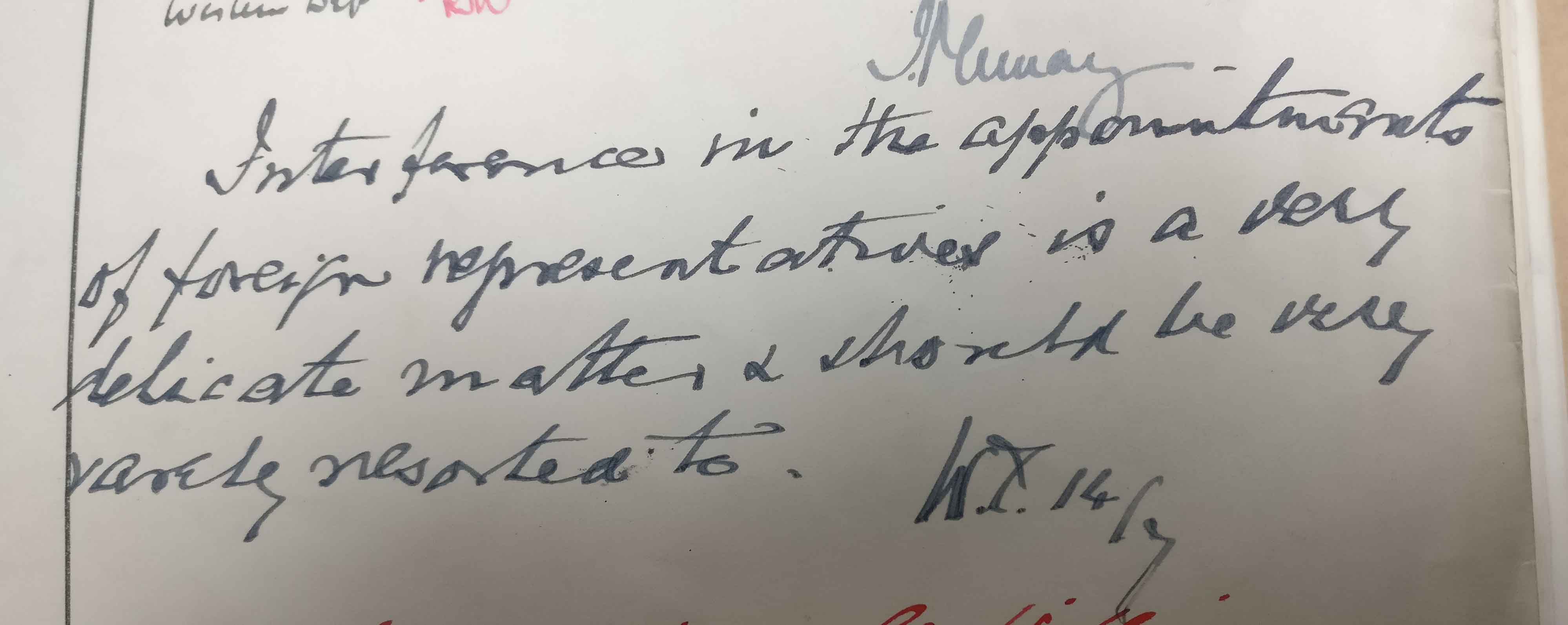

William Tyrrell, the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, warned that ‘interference in the appointments of foreign representatives is a very delicate matter and should be very rarely resorted to’ (FO 371/11608).

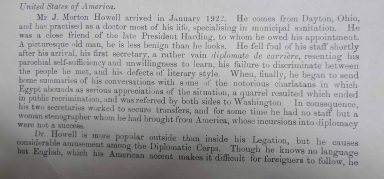

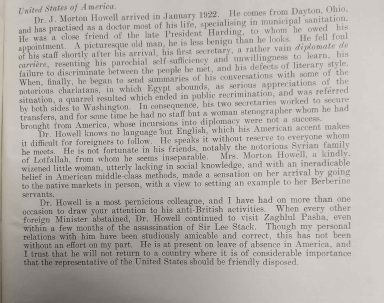

The 1925 Report on the Heads of Foreign Missions had described Howell’s antics, with a passing reference to his unpopularity within the American Mission:

‘Dr. Howell is more popular outside than inside his legation, but he causes considerable amusement among the Diplomatic corps (…). Alone in Egypt he drives out in the morning in a top hat and a frock coat’ (FO 371/10906).

By 1926, any hint of amusement had vanished, and the Report was scathing. ‘A picturesque old man, he is less benign than he looks’, the report stated; he had managed to alienate all embassy staff almost immediately and was a ‘most pernicious colleague’.

- 1925 Report on the Heads of Foreign Missions (catalogue reference: FO 371/10906)

- 1926 Report on the Heads of Foreign Missions (catalogue reference: FO 371/11608)

By November 1926, ‘the anti-British activities of Dr Howell had become increasingly intolerable’, and were starting to have an adverse effect on the British position in Egypt. On 29 November 1926, the New York Times, to which Howell allegedly leaked all sorts of apocryphal stories, reported:

‘The return of the King [of Egypt] to Cairo from Alexandria has given rise to a diplomatic incident the result of which is being awaited with curiosity’ (FO 371/11608).

The King had left the station by the royal gate, followed, as protocol dictated, by the Princes of the Royal Family and the British High Commissioner. Representatives from other countries had to leave through other exits. Morton Howell seemed to have strongly resented the special treatment of the British representative, and protested very vocally.

The French Minister assured Lloyd that Howell’s ‘outbursts were not taken seriously’ and that the special position of the British High Commissioner, in force since Egypt had become independent in 1922, was not being questioned by anyone else.

Lloyd, however, was losing patience. Complaining that Howell was also introducing American visitors to Anglophobe Egyptians, he asked again that the American Minister should be removed. He wrote to the Foreign Office:

‘Argument that his clumsiness and stupidity prevent him from doing us any harm is I consider a fallacy in present circumstances (…). I can if necessary supply you with a number of minor proofs of his offensiveness’ (FO 371/11608).

Arthur Wiggin, at the Residency, reiterated the point: ‘the High Commissioner is most anxious to get rid of this nefarious old fool as soon as possible’ (FO 371/11608).

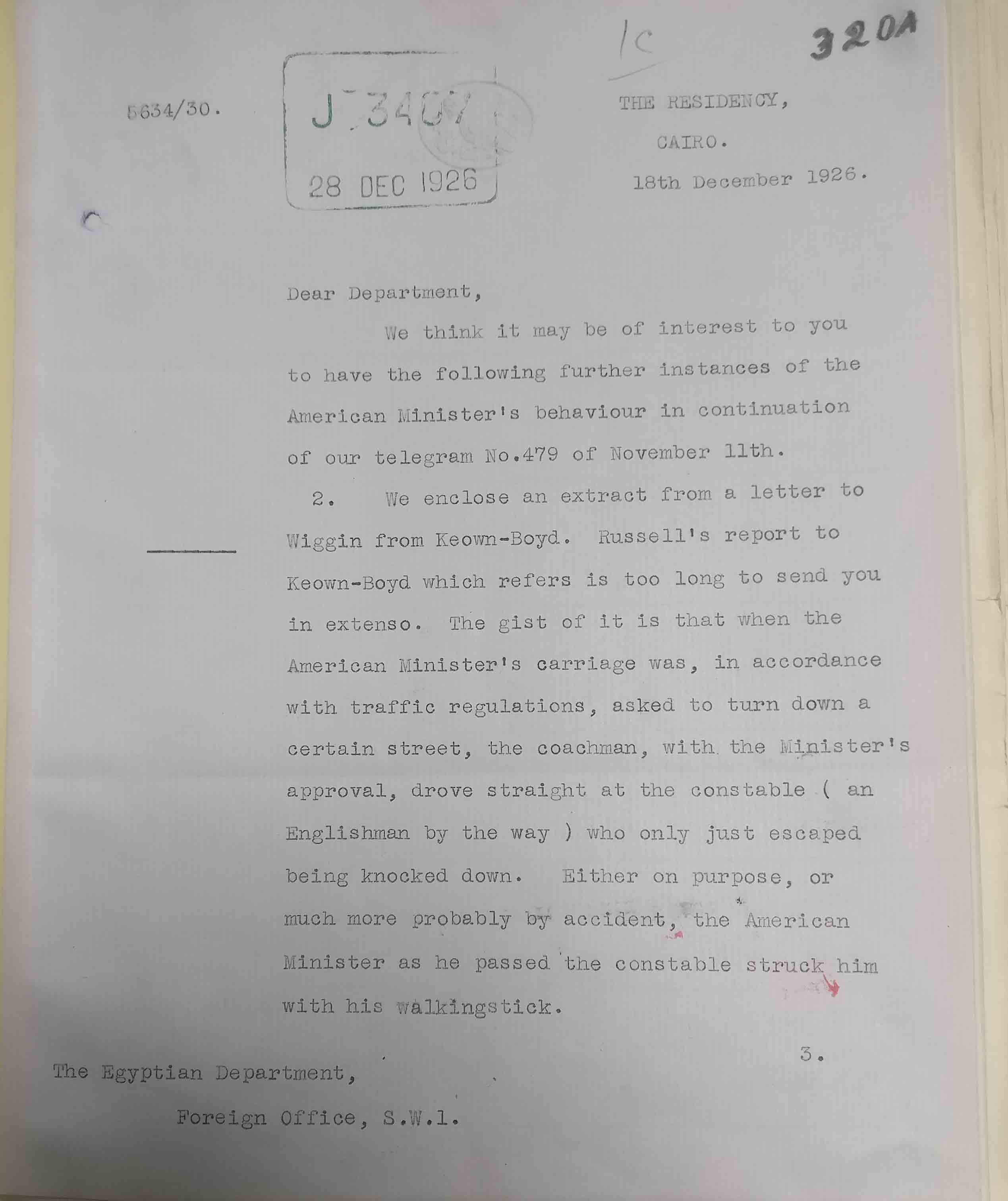

Lloyd then started documenting everything. There is a rather surprising number of Foreign Office files entitled ‘Activities of American Minister in Egypt’ in our collections, describing all of Morton Howell’s sins. In December 1926, for instance, his carriage was asked, in accordance with traffic regulations, to turn down a specific street. Howell, probably assuming the law didn’t apply to him, instructed the driver to drive straight at the (British) constable. The constable was unharmed, but, Lloyd reported, ‘either on purpose, or much more probably by accident, the American Minister, as he passed the constable, struck him with his walking stick’. Howell later drove through another three traffic officers and almost rammed into the High Commissioner’s car (FO 371/11608).

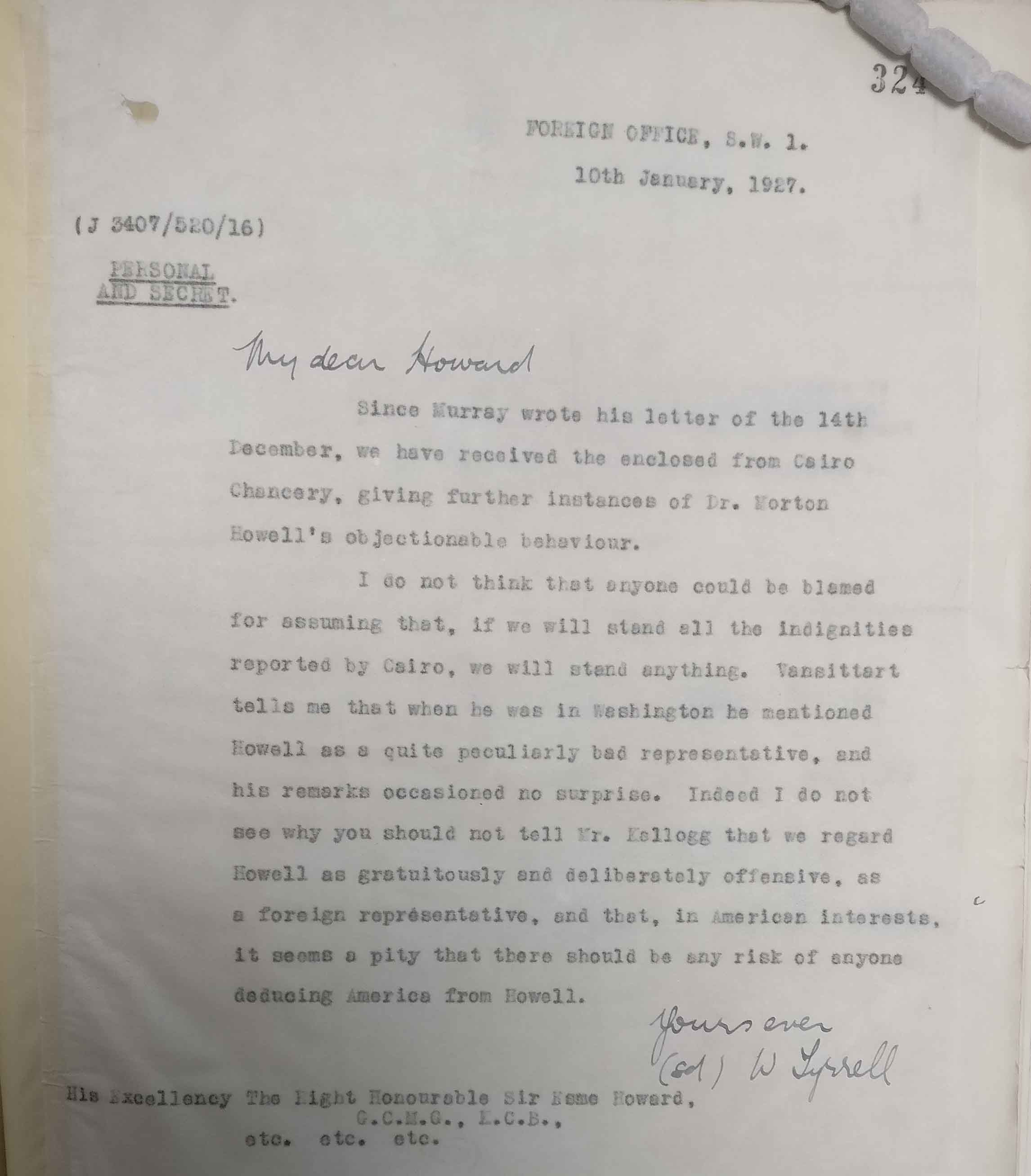

In January 1927, as Howell’s activities assumed what the Foreign Office described as a ‘more serious character’ (FO 371/12371), William Tyrrell wrote to Esme Howard, the British ambassador to Washington:

‘I do not see why you should not tell Mr Kellogg [the American Secretary of State] that we regard Howell as gratuitously and deliberately offensive, and that, in American interests, it seems a pity that there should be a risk of anyone deducing America from Howell’ (FO 371/11608).

When the (British) Commandant of Cairo City Police issued a notice asking that omnibuses licensed in the future should, for security reasons, be of specific dimensions, Howell lashed out, attacking this particular policy and the British in general. His syntax was a bit shaky and his punctuation virtually non-existent (one can’t help but feeling sympathetic to those of his staff who expressed dismay at his literary style), but the message was quite clear:

‘We cannot but express our surprise that a matter of such import should be left to a gentleman, incidentally not an Egyptian, to solve by withholding licenses from individual owners of vehicles numbering more than 2,000,000 dollars capital and livelihood of thousand Egyptians by thus arbitrary suppressing their business and that too on a month’s notice’ (FO 371/12371).

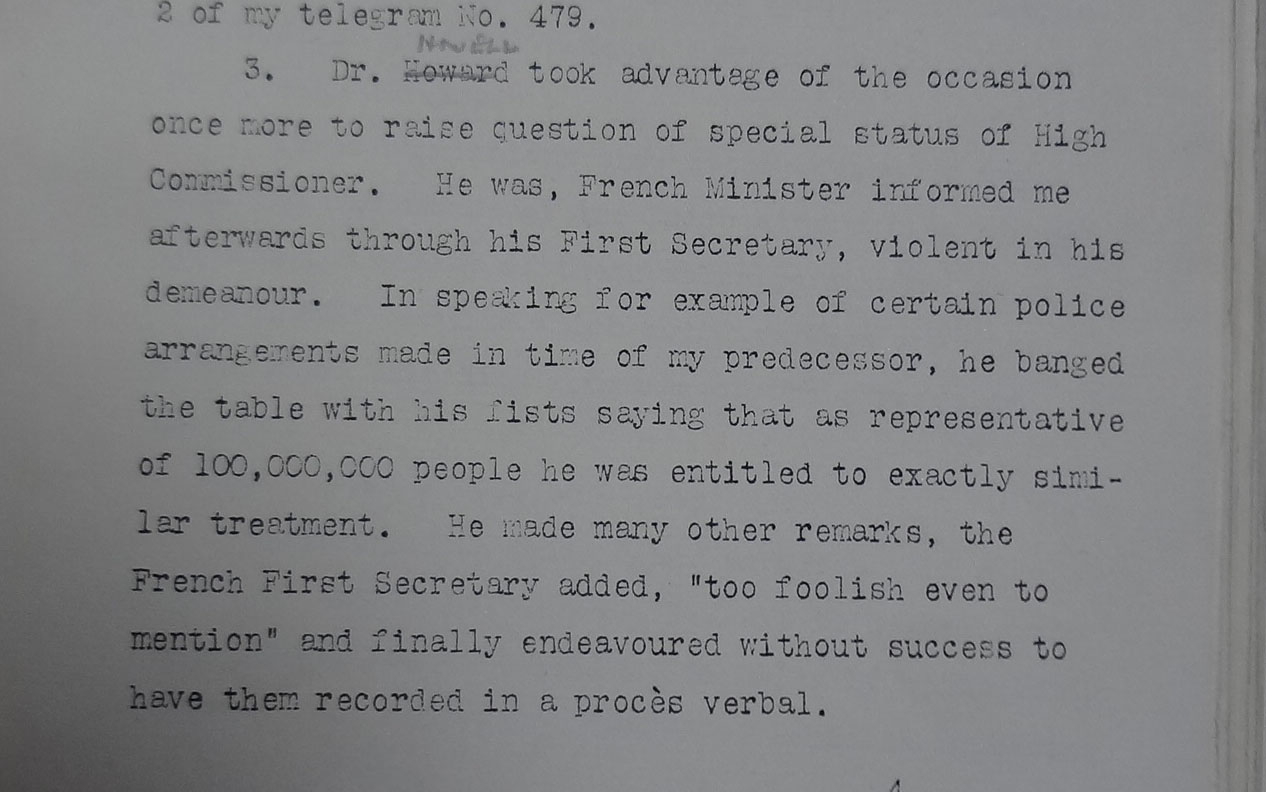

This statement was both factually incorrect and likely to create political tension between Egypt and Britain. He repeated it at a meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where, according to the French Minister, he was ‘violent in his demeanour’.

Soon after the incident, Lloyd reported that even the American consul was no longer on speaking terms with Morton Howell, and that ‘there was no American of any standing in Egypt who would not welcome [his] disappearance’. He asked, once again, that the Foreign Office make representations to the American government. In Washington, Howard received clear instructions: ‘make use of this material in whatever way you consider likely to prove most effective’ (FO 371/12371).

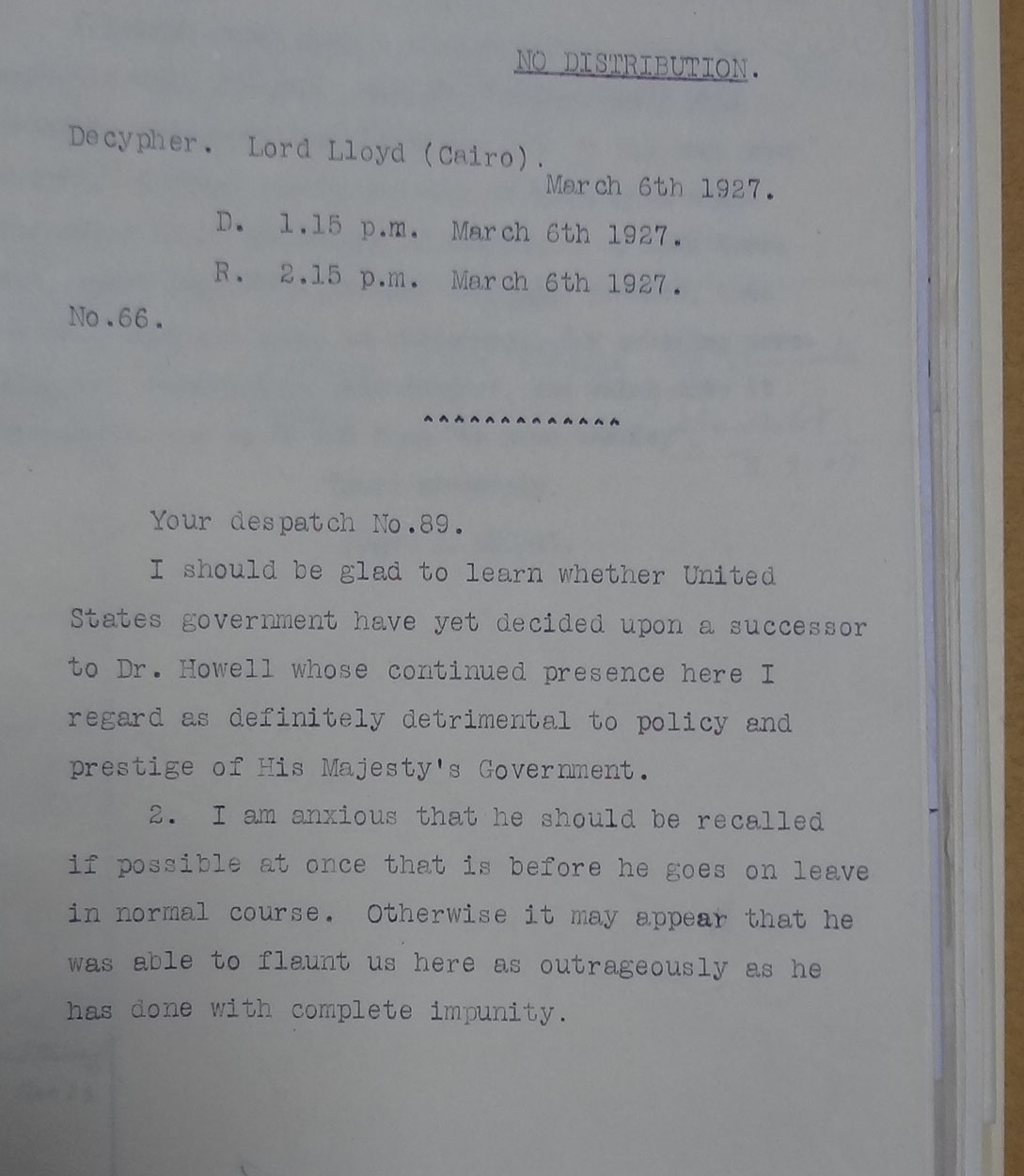

The worst Howell seems to have done in February was showing up unannounced at the Egyptian State Telegraphs and Telephones building, which was definitely frowned upon, but, by March, Lloyd was getting somewhat desperate. He telegraphed the Foreign Office: ‘I am anxious that he should be recalled if possible at once’.

There was no question of putting pressure on the Americans to ‘name the day’ for Howell’s departure or to recall him swiftly, but the Foreign Office hoped the Department of State, which was becoming increasingly nervous about their own representative, may convince him to resign shortly.

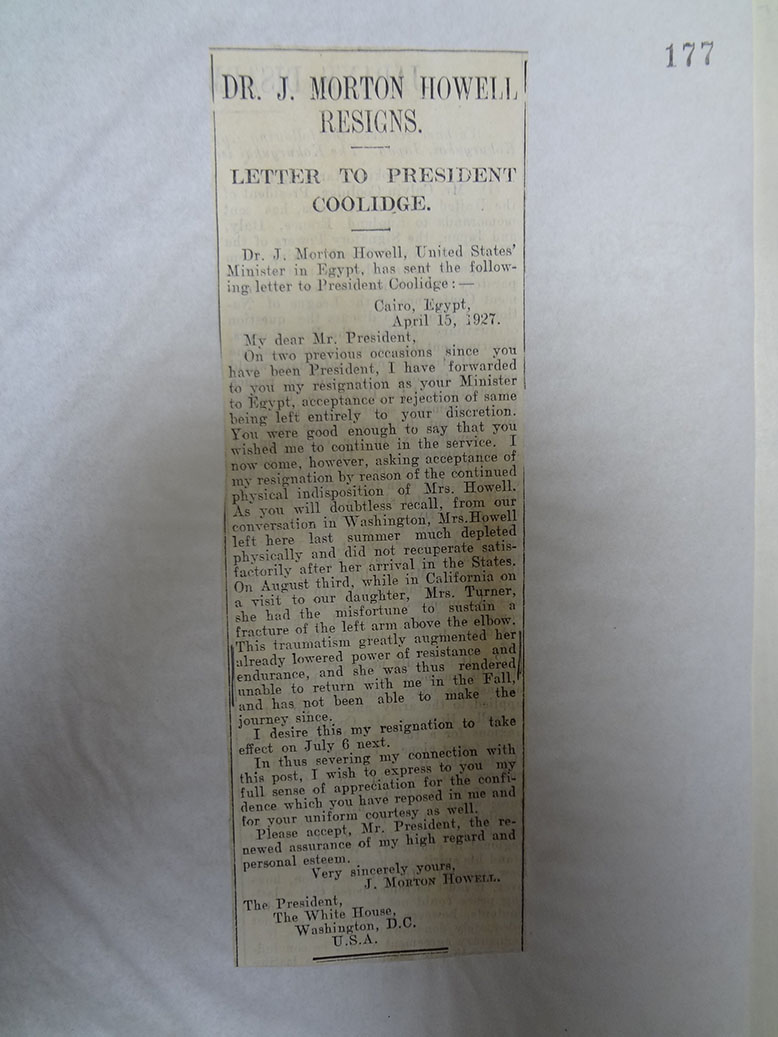

On 6 May, quite unexpectedly, Morton Howell called in person at the offices of two local British papers in Cairo and handed them carbon copies of the resignation letter he had sent to President Coolidge. Lloyd, clearly immensely relieved, reported:

‘Dr. Howell’s method of communicating this letter to the press combined with the inappropriate and unconvincing nature of its contents have evoked general amusement’ (FO 371/12371).

At the Foreign Office, the Head of the American Department, Robert Vansittart, commented: ‘a good riddance’.

Morton Howell’s resignation letter as it appeared in the Egyptian Gazette (catalogue reference: FO 371/12371)

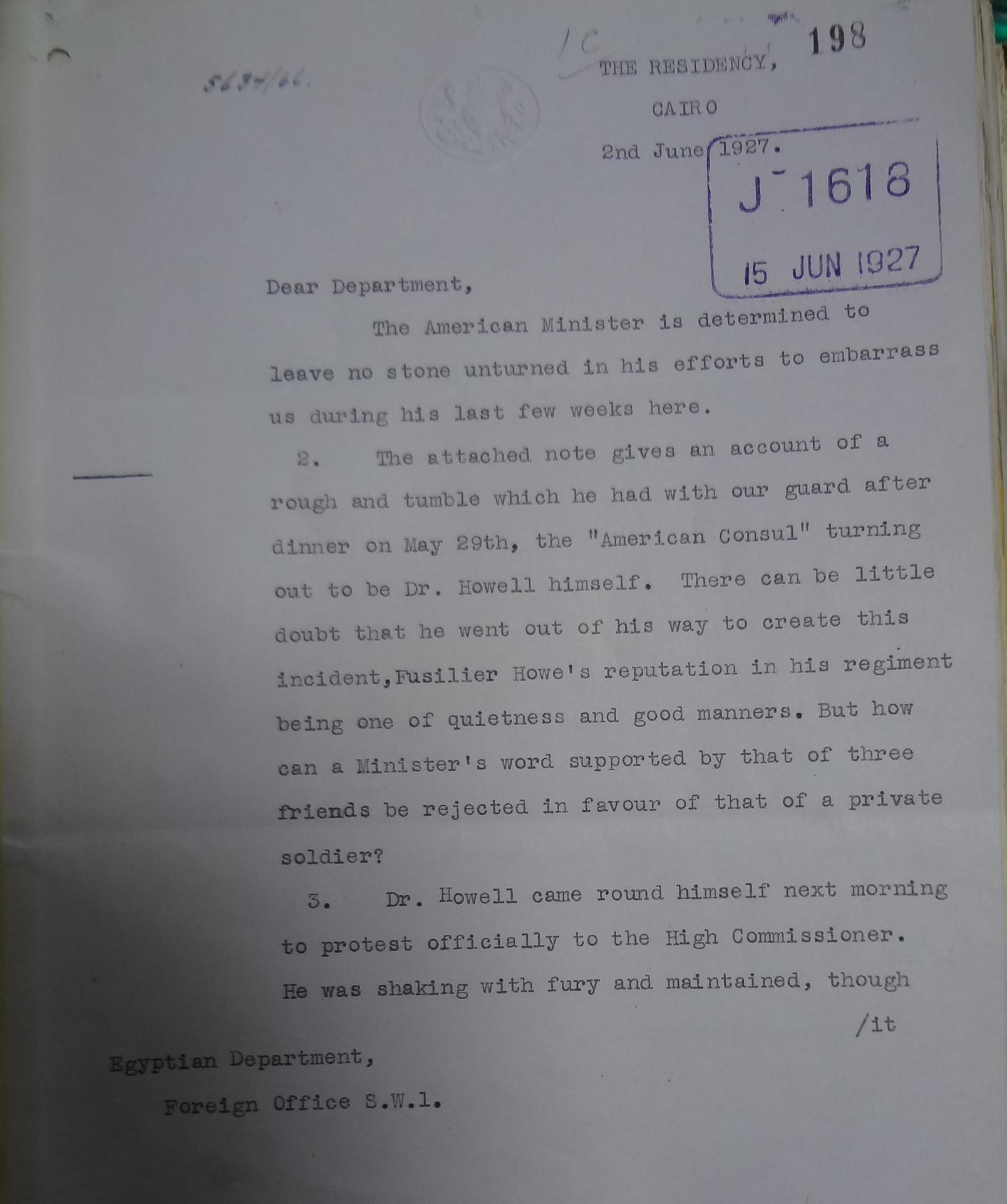

George Lloyd’s amusement, however, was to be short-lived. First, Howell would only leave Egypt on 6 July, which, for the High Commissioner, was an almost unbearable wait. Secondly, Howell kept running what the Foreign office described as ‘an anti-British campaign’ in the Egyptian press. Thirdly, he had ‘a rough and tumble’ with one of the Residency’s guards, which prompted Lloyd to comment: ‘the American Minister is determined to leave no stone unturned in his efforts to embarrass us during his last few weeks here’ (FO 371/12372).

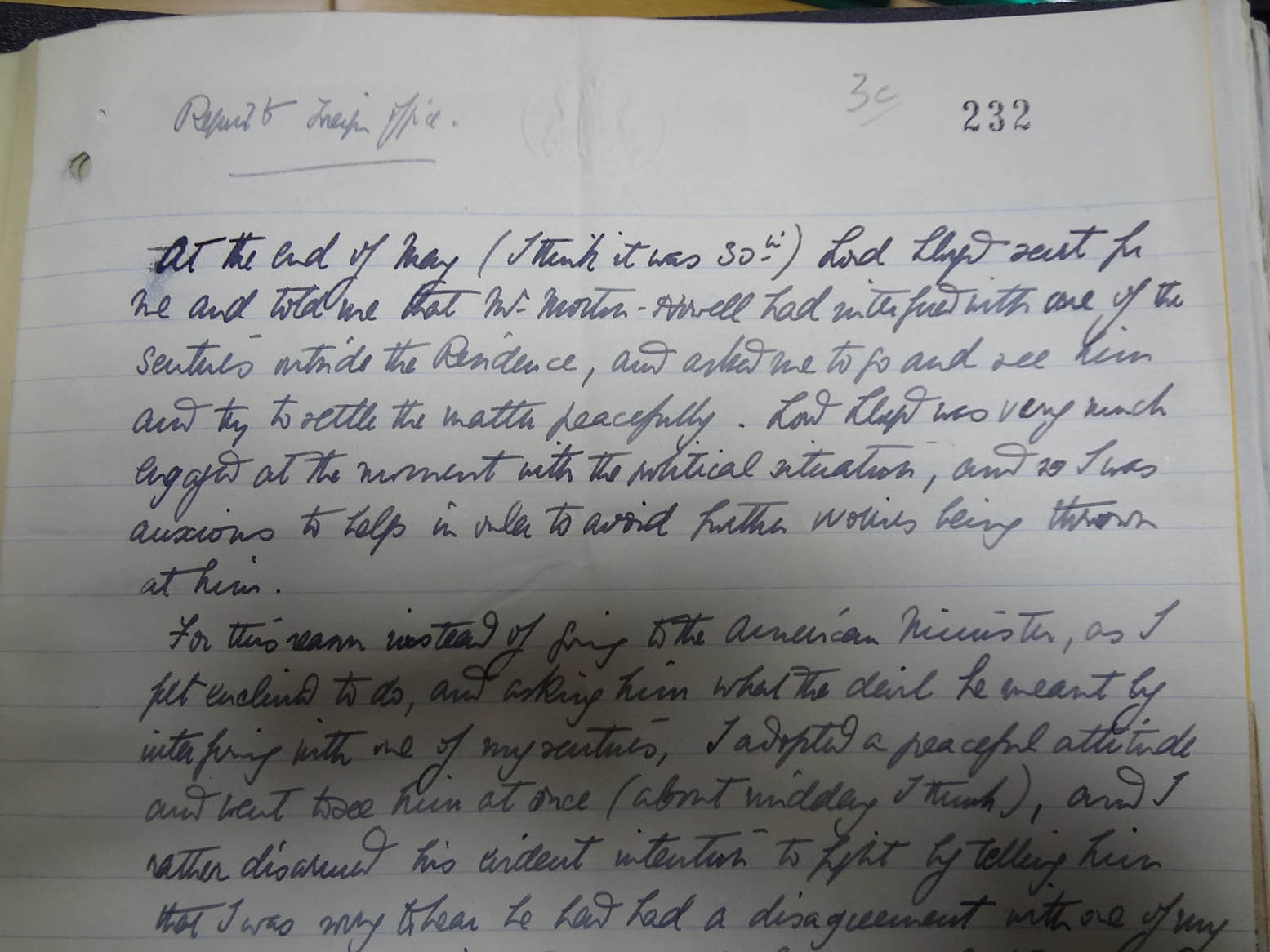

The incident in question can seem silly, but the General Officer Commanding the British Troops in Egypt, General Sir Richard Haking, thought Howell had created it on purpose ‘because, for some reason or other, he appeared to dislike Lord Lloyd’. On 29 May 1927, after dinner and as it was quite dark, a sentry posted outside the Residency told Howell and two of his friends that they could only pass in front of him, not behind. They refused to comply. Twenty minutes later, the scene was repeated, and the sentry was pushed towards the railings, bumping into the two persons behind him in the process. Howell made furious complaints to Haking, and his version of the incident, which also appeared a few weeks later in the papers, was considerably different from that of the sentry.

General Haking didn’t want to fuel the tension between Lloyd and the soon-to-be-gone American Minister, which is why, he reported,

‘instead of going to the American Minister, as I felt inclined to do, and asking him what the devil he meant by interfering with one of my sentries, I adopted a peaceful attitude’ (FO 371/12372).

General Haking’s report to the Foreign Office, 22 September 1927 (catalogue reference: FO 371/12372)

Morton Howell finally left Egypt on 6 July, and as far as can be judged from surviving Foreign Office files, wasn’t heard of again. His behaviour, ‘not consonant with any conception of diplomatic functions of Minister of a friendly country’, hadn’t endeared him to the Department of State which, according to the British Embassy in Washington, had come to regard him ‘as somewhat of a buffoon and a good deal of a nuisance’ (FO 371/12372).

I hope, however, that you will agree with me that, as the Foreign Office put it, Morton Howell displayed ‘a sufficiently novel conception of diplomacy to cause – well, comment!’ (FO 371/12372).