This blog is based on letters that the Prize Papers Project have published online today as part of a large selection of records taken from neutral ships during the War of the Austrian Succession. Images of the original letters are now available in the Project’s web portal here along with many others taken from the ship Franciscus of Hamburg in 1744.

Over the next 15 years, the Project will publish images of around 500,000 letters and papers taken from ships c.1650–c.1815, which originate from across the world and are written in dozens of languages. The Prize Papers is a vast unexplored collection for global and colonial history of value to researchers across the world.

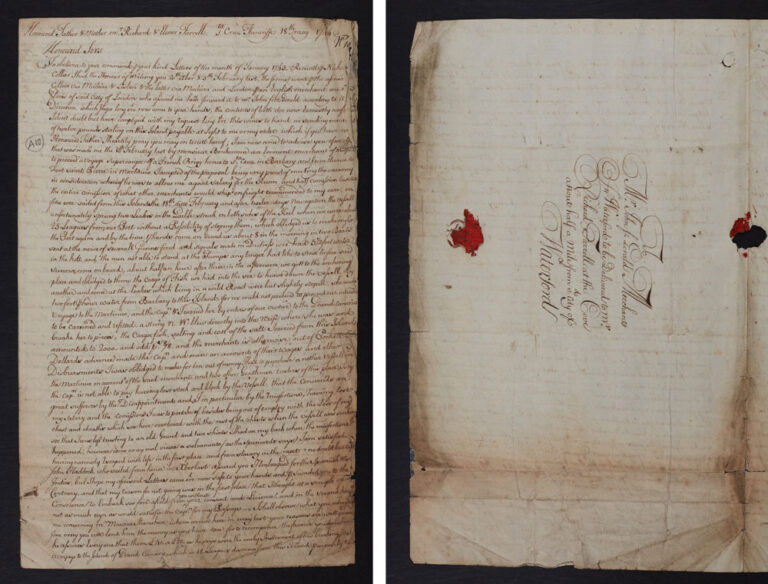

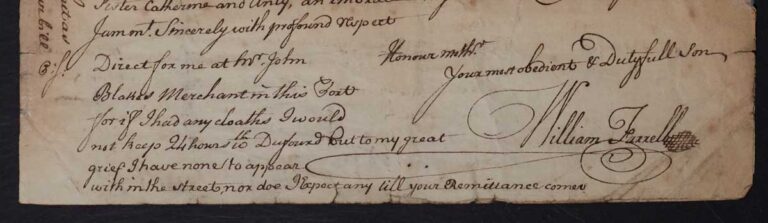

Three remarkable letters written in May 1744 survive at The National Archives, which were penned by the down-and-out Irish merchant William Farrell while he was in Santa Cruz, Tenerife, intended for members of his family in Waterford. Each is long and rambling, as Farrell was still delirious from a violent fever that left him ‘ready to be stretcht to be put into my coffin’.

Together, his letters provide a disjointed autobiography, detailing the aspiring merchant’s life over the previous four years, as he tried and mostly failed to negotiate the perils of life in the eighteenth century. Each line yields amusing and affecting details, making them a far cry from most letters sent in this period, which often seem stilted and impersonal to modern readers.

More than just a story of one man’s adventures, Farrell’s letters also bring to life a sprawling and little-known Irish diaspora that stretched from Ireland to the Canary Islands and into Spanish colonies in the Americas. They show how this community lived and died by the entwined bonds of family and business, in a time when no information could travel faster than a ship could sail.

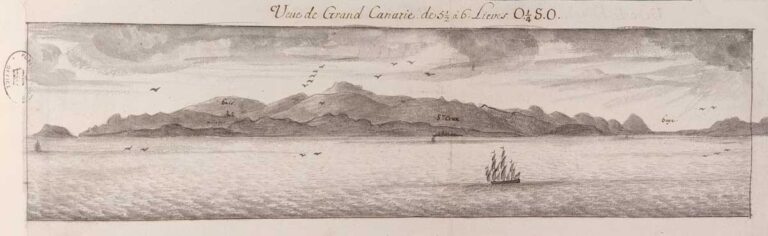

Tenerife: a gateway

William Farrell was the Catholic son of a lesser gentry family with lands about half a mile outside Waterford, and he emigrated to Tenerife around 1740 to be apprenticed to an Irish merchant, probably John Blake of Ballinakill, Co. Galway.

While the idea of an Irish Catholic community existing on this Spanish-owned island may seem surprising, Tenerife had a significant Irish population from the mid-seventeenth century, split between the towns of La Orotava and Santa Cruz. They were drawn to the island because it was an entrepôt, where many ships called before sailing on to ports in the Mediterranean and to Spanish colonies in the Americas.

Catholics were also driven from Ireland in large numbers during the eighteenth century as the Protestant-dominated government enforced laws that hampered the financial prospects of Catholics. Emigrants like Farrell were drawn to Tenerife as a majority-Catholic gateway to the Spanish Empire that welcomed foreign merchants.

He relocated to Tenerife at a bad time, however. The War of the Austrian Succession erupted in December 1740, which put Britain and Ireland at war with Spain, outlawing direct trade between Tenerife and his Irish contacts. Privateering was also widespread during this war and its impact on trade brought many supposedly great merchants at Tenerife to bankruptcy.

Farrell’s lack of success in this environment is evident from the fact that, in early 1742, he considered signing on to a Spanish privateer as a lieutenant, but eventually opted not to, as, he claimed, ‘if the English should take me Priviteering they’de hang me Round as a hoop’. Here, he feared being executed for treason if he signed up, as the English crown forbade its Irish subjects from serving on enemy ships during wartime. Farrell must have been desperate for money to even consider it.

Duelling for honour – and trust

Farrell then writes of his voyage from Tenerife to Gran Canaria in May 1743, to collect on a debt of £40 (roughly £8,000 today). His father Richard had lent the money to another Irish merchant, Maurice Shanahan, who was rumoured to now be resident at Gran Canaria, but when William Farrell arrived on the island, the debtor was nowhere to be found. Instead he bumped into the Shanahan’s brother, who invited him to dinner with his family that day to discuss the matter.

Conversation over dinner turned sour when Farrell raised the debt, as one of the hosts claimed that Farrell’s father was attempting to destroy Maurice’s credit by calling in the loan when the debtor had no money. Farrell became furious at the allegation and ‘got up and put on my sword in a fury telling [him] he was no man of honour to give me an invitation with a design to affront my friends and parents after that manner’.

The next day, he was still in such a rage that he drafted a letter to Maurice Shanahan challenging him to a duel over the insult, writing that he would ‘give him public or private satisfaction at sword and Pistill’, although the debtor then dismissed the incident as a misunderstanding.

The anger brought to the surface by this dispute is a reminder of the emotional investment that eighteenth-century men had in personal and family reputation. While Farrell felt compelled to reply to a slight on his father’s honour by appearing willing to risk injury or death in a duel, the women present at the dinner withdrew from the dispute when it looked to become violent. Yet if Farrell’s reaction was gendered, it was not necessarily irrational. Irish communities in the Canary Islands and throughout the diaspora were tight knit, and if his father was seen as a dishonourable creditor it violated in-group trust, meaning that neither he nor his family would be trusted as trading partners. Reputation had to be preserved, or they could be made destitute.

Farrell writes of another occasion when his temper got the best of him, but this time with dire consequences. One evening in November 1743, he was drinking in a tavern with William Hays, one of La Orotava’s wigmakers, and the two fell into a heated disagreement. The quarrel escalated into a scuffle in the street and during their fight the wigmaker drew his sword, stabbed Farrell through the chest and then fled the scene.

Farrell was fortunate as he was immediately picked up by passers-by and carried to the house of a local notary public, who sent for a doctor but also a priest. On arrival, the priest did not like Farrell’s chances and read him his last rites, but the doctor was then able to staunch the bleeding and tend to the wound. As no infection set in, Farrell was well enough to leave the notary public’s house after just three weeks.

A fresh start?

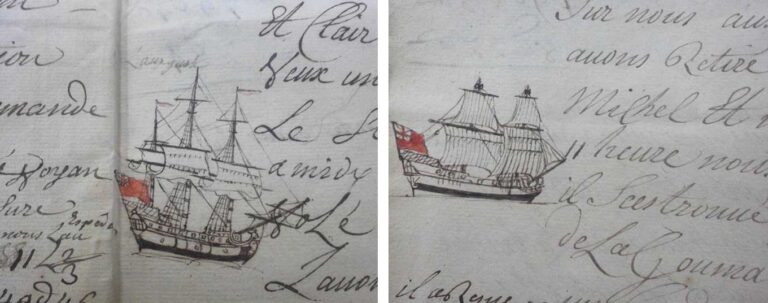

A brush with death put him in mind to leave Tenerife and seek new opportunities across the Atlantic. In February 1744, Farrell talked his way into acting as supercargo (a representative of a ship’s owner) on a ship belonging to the French merchant Jean Bonhomme, which was bound to Morocco and then Martinique in the French Caribbean.

This vessel sailed with Farrell aboard on 18 February 1744 and they had only made it 25 leagues when disaster struck. One sailor noticed a leak in the stern that was causing the ship to fill with water and the crew immediately panicked, altering course back to Tenerife. As the water level rose, the captain ordered the crew to throw the cargo and their personal possessions overboard to reduce their weight. It was a measure that likely saved their lives – the water was 5½ feet deep in the hold when they again reached Tenerife.

The disasters began to mount for Farrell, who was now back where he started, having thrown all of his worldly possessions into the Atlantic.

The situation went from bad to worse when he then fell sick on 28 March and was carried to the house of Pierre Dufourd, a French diplomat in Santa Cruz. Farrell battled dysentery for three weeks and his condition was so bad that he was ‘given over by the doctor three times’ and yet, miraculously, he survived. It then turned out that there was a catch to Dufourd’s hospitality, as Farrell was obligated to stay in the house and tutor the diplomat’s two illegitimate sons, probably as payment for medical debt.

It was this final misfortune that prompted him to write to his family in Ireland and relay all that he had recently endured. In a letter to his mother, Farrell stated that he only had ‘2 shirts in the world and them are Entirely in strings’ meaning that ‘I can’t goe even to mass Except before Day and am always a Prizoner in [this] House because I have no close [clothes] but an old gound [gown]’. He hoped that his ordeals would induce his family to send money, so that he could escape Dufourd and, finally, get himself off Tenerife.

His letters would never reach his family in Waterford, however. Farrell entrusted them to the captain of the ship Franciscus, which sailed for Hamburg on 20 May 1744, but it was intercepted by a British privateer en route. The privateer took the Franciscus into Dover, where its crew removed around 600 letters from the captured ship, including Farrell’s, and sent them to the High Court of Admiralty in London as evidence that could prove the legality of the capture. While his family never saw the letters, you now can as they are now available online in the Prize Papers Portal, along with all of the papers taken from the Franciscus.

You can find more details about the Franciscus here and view its papers in the Prize Papers Portal. You can also read about all of the neutral ships and their papers that have been published online today. A film about Farrell’s life is available here.

Interesting story. Shows how important trust was in times past. But what I really loved was the snippet of handwriting which is a joy to look at.His signature is a work of art.