Please be aware that this blog includes some graphic content and may not be suitable for all readers.

On 29 June 1634 the Privy Council wrote to Alexander Baker and William Clowes, both surgeons in royal service, ordering them to gather a group of midwives and ‘inspect and search the bodies of those women that were lately brought up by the sheriff of the County of Lancaster indicted for witchcraft’[ref]SP 16/270 f.134. For ease of reading I have modernised spellings when quoting from original documents.[/ref].

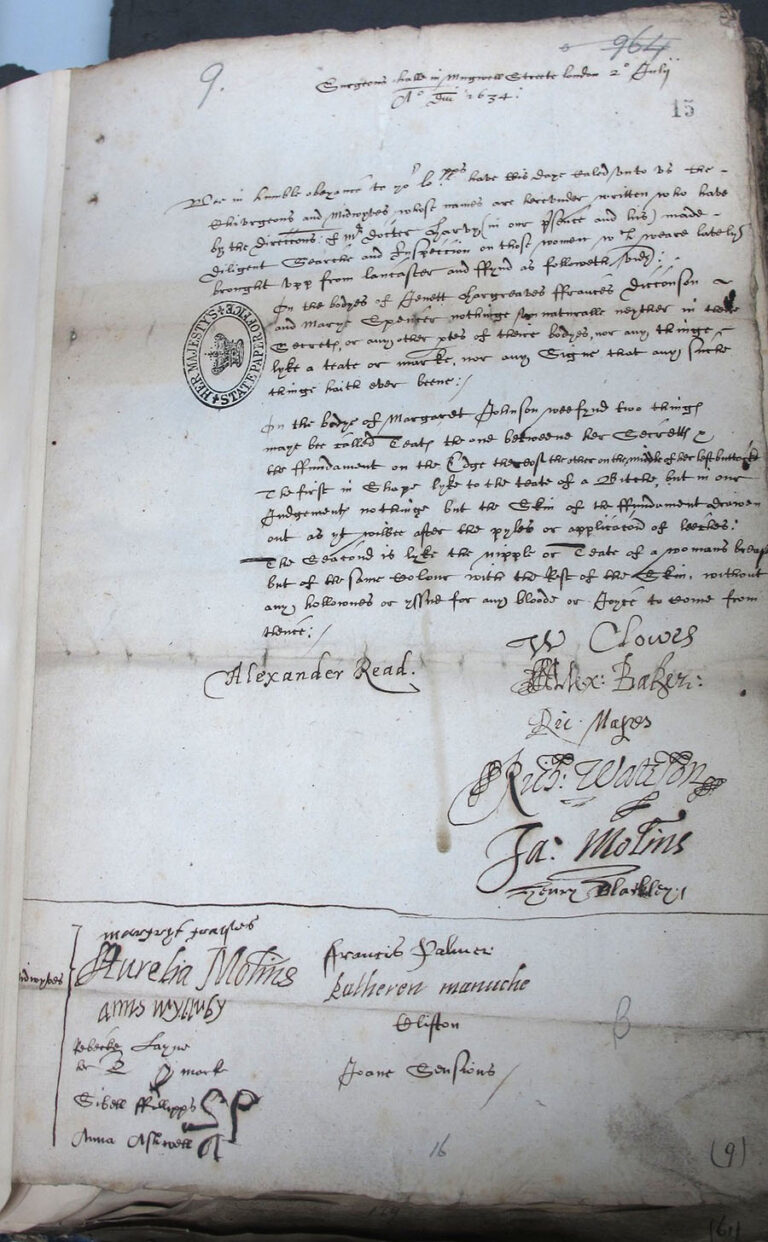

Having received their orders, Clowes gathered a group of surgeons and midwives and carried out the examinations on 2 July. They provided a certificate, place dated at the Surgeons’ Hall in Mugwell Street and signed by themselves, some surgical colleagues, and a number of midwives, which outlined the results of their examination. The certificate stated that they had made ‘diligent searches and inspections on those women … and find as follows: On the bodies of Jenett Hargreaves, Frances Dicconsen and Mary Spencer, nothing unnatural neither in their secrets or any other parts of their bodies… On the body of Margaret Johnson we find two things may be called Teats the one between her cervix and the fundament… the other on the middle of her left buttock. The first is shaped like to the teat of a bitch but in our judgement nothing but the skin of the fundament drawn out as it will be after the piles of application of leeches. The second is like the nipple or teat of a woman’s breast but of the same colour with the rest of skin without any hollowness or issue for any blood or juice to come from thence.’[ref]SP 16/251 f.15.[/ref]

In other words, they had found nothing odd at all on the bodies of three of the women, and on the fourth there were a couple of growths but nothing that the examiners thought sinister. But why were these women being subjected to this examination in the first place? What were the surgeons and midwives looking for? And why was the Privy Council, the elite group of advisors around the king, interested in four women from rural Lancashire? The answers to these questions shine a light on a witchcraft scare that rocked 17th-century England, and tell us much about beliefs in witchcraft and how they affected ordinary people at that time.

The story begins in late 1633, when a small boy, Edmund Robinson, started making accusations of witchcraft against women living in his neighbourhood in Lancashire. Soon, other neighbours started making similar accusations, and within a few months a large group of women, and a few men, were on trial for their lives at Lancaster Assizes. Many of them were found guilty, but the judge who presided over the case was uneasy about the verdict, and referred the case to the Privy Council.

The Privy Council undertook its own investigation, asking the Bishop of Chester to interview some of the accused women and going so far as bringing them, as well as young Edmund Robinson himself, to London for further examination. It’s not clear exactly why the judge was concerned, or why the Privy Council agreed with his concerns.

In 17th-century Europe witchcraft was very much a fact of life; no one would have questioned the existence of witches, or the belief that they could use sorcery to cause harm. The Witchcraft Act of 1563 had established witchcraft as a felony in England and Wales and, as such, suspected witches could be tried in the assize courts. The assizes were by no means swamped with witchcraft cases, but there was a steady stream of trials of accused witches which passed off with no intervention from central government.

It may have been the scale of the witch scare in Lancashire that concerned the authorities. While most cases at the assizes concerned one or two people (usually, although not invariably, women), in this case around 19 people were put on trial. Moreover, there had been another mass witch trial at the Lancaster Assizes 20-odd years before, which had resulted in the hanging of 10 people[ref]This is the infamous case of the ‘Pendle witches’, tried in 1612; the assize records do not survive.[/ref]. Perhaps the Privy Council was thus concerned to find out for itself whether Lancashire really was a hotbed of witchcraft, and we should certainly not assume that it was automatically sceptical about the accusations.

One of the key problems facing anyone involved in witchcraft investigations or trials was the issue of evidence. Allegations of witchcraft frequently blamed the accused for naturally-occurring events – the illness or death of people or livestock, the failure of crops, even sexual dysfunction. But to ‘prove’ that this was the fault of a witch rather than just misfortune was very hard. Elsewhere in Europe, suspected witches could be tortured into confession, but under English law, torture was illegal. Suspected witches were occasionally subjected to ordeals such as ‘swimming’, whereby the accused was dunked into a river in an attempt to prove guilt or innocence. But where this happened it was usually carried out by local communities and was not part of the normal functioning of the justice system.

But there was one element of English witch beliefs that did provide the possibility of physical evidence – the belief in ‘familiars’. These were demons who helped the witch with her sorcery. They were believed to take the form of common animals and feed on the blood of the witch – leaving tell-tale marks which were thus considered physical evidence of witchcraft.

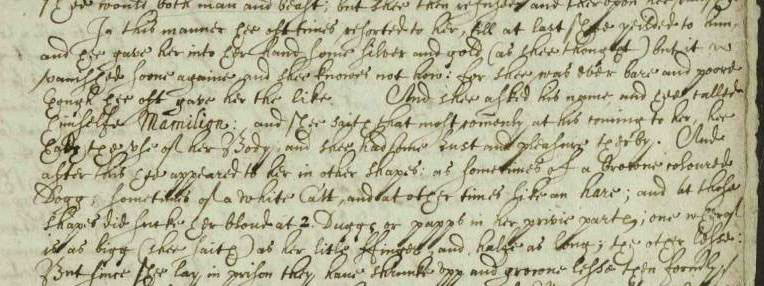

It is these marks that the surgeons and the midwives were looking for in the inspection certificate mentioned above. Indeed, a letter from the Bishop of Chester to the Privy Council recording his conversation with Margaret Johnson, one of the accused women, states that Johnson herself claimed to have familiars. She described how she was visited by the devil ‘sometimes as a brown coloured dog, sometimes as a white cat and at other times like an hare’ and that she had ‘two duggs or papps in her private parts’ where the familiars sucked her blood[ref]SP 16/269 f.174.[/ref].

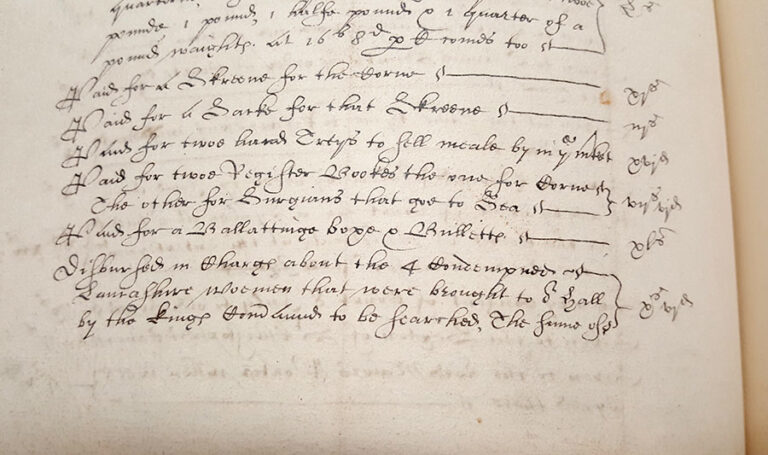

The surgeons and midwives thus knew exactly what they were looking for yet, as we have seen, found nothing that they considered to be sinister or only explicable as a mark of witchcraft. Midwives, of course, were experts in female anatomy. They were also often relatively well-educated and frequently literate (a number of the midwives in this group signed their own names on the certificate). One of the midwives listed, Aurelia Molins, was married to one of the surgeons listed, James Molins. The surgeons named on the certificate were all professional men and members of the Barber-Surgeons company; several of them were in royal service. The accounts of the Barber-Surgeons’ company from the period carefully noted the disbursement of 10s 6d for the examinations of the four women, ‘brought to our hall by the King’s command to be searched’[ref]Wardens’ Yearly account and audit book covering 1603-1659 (archive ref D/2/1 p308v). Also printed in Sidney Young ed., Annals of the Barber-Surgeons, (London, 1890) p.401. My thanks to Victoria West, the archivist of the Worshipful Company, for supplying this image as well as a great deal of kind and helpful assistance.[/ref]. Yet as with the Privy Council, we should not simply assume that this group was sceptical about witchcraft. Belief in witchcraft was prevalent at all levels of society, even among the most highly-educated (indeed in 1597 James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, had published his own compendium of witchcraft lore).

References in contemporary literature regularly make reference to women giving evidence in court that they have found suspicious marks upon the bodies of accused witches. But certificates such as this one, providing documentary evidence of exactly what was done, what was found, and by whom, are extremely rare. It is stark, disturbing evidence of what was done to ordinary people, by other ordinary people. No matter that in this case nothing sinister was found; for Jenett Hargreaves, Frances Dicconsen, Mary Spencer and Margaret Johnson, the examinations themselves must have been a degrading and traumatic ordeal.

Witchcraft is a subject in which there is enormous interest, but these documents remind us that stories of historical witch scares are not fantasies invented to thrill us, but the histories of real people, accused of terrible crimes and subject to terrible suffering as a result.

For further discussion of this case and others, please tune into the latest series of our On the Record podcast.

On the Record: Trials available now

In our latest three-part podcast series we are exploring stories from our collection which tell the history of trials; from witch trials and trial by combat to today’s legal system. In the series you’ll hear about a famous cannibalism case as well as legal evidence preserved in our archives which reveal LGBTQ spaces otherwise lost to history. You’ll also hear how archives themselves are evidence of the past.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which we have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and lost love letters within our collection. Most recently we have investigated four deadly pandemics and epidemics that changed lives in the UK over the last 600 years.

We have also a history of Witchhunting in Belgium. In my own region of Bruges and West Flanders

several witches were burnt, in total 97 between 1468 and 1651.

Is there any record of what happened in later life to the poor women who were “examined” ?

Torture was I believe not illegal if authorised by the King.

In response to Johny Recour:

Hello – thanks for your comment, that’s really interesting. Trials for witchcraft took place across Europe, with some areas persecuting alleged witches much more actively than others. In England condemned witches were hanged rather than burnt in line with the status of witchcraft as a felony under the common law.

In response to pw:

Hello – thanks for your question. Documentary evidence shows that three of the women – Jennet Hargreaves, Mary Spencer and Jennet Dicconson – were still in prison in Lancaster jail in August 1636 (alongside six of others convicted in the case). There is no mention of Margaret Johnson; it’s possible that she had been released, but it’s also possible that she had died in jail. (Three of the group initially tried at the assizes died in jail prior to the Privy Council investigation.) As far as I am aware, we have no records which shed any further light on their fates.

In response to David Matthew:

That’s correct; it could be authorised by the monarch or the Privy Council. In practice this was usually done in cases of treason, the most famous example being the Gunpowder Plot.

I agree that decisions on the use of torture was supposedly reserved for the monarch, but, like those on waterboarding in the US, this was not much of a restriction. To quote L A Parry (1933): “Under Henry VIII it [torture] was frequently employed; it was only used in a small number of cases in the reigns of Edward VI and Mary. It was while Elizabeth sat on the throne that it was made use of more than in any other period of history” and “The rack seldom stood idle in the latter part of Elizabeth’s reign.” There was also the infamous “Peine forte et dure” which was still being used in Salem, Mass in 1692.

Elizabeth’s pet torturer was Sir Richard Topcliffe, who was so immersed in his work that he developed a portable rack that he could take with him on consultations.

In John Langbein’s Torture and the Law of Proof, University of Chicago Press, 1977, it says that more than 25% of torture warrants were issued for “ordinary” crimes like murder, burglary, robbery, and horse stealing.

Whoops!

Parry’s book is “The History of Torture in England”

[Less important; “was” in the first line should be “were”]

Sorry!

[Next time, I should proof-read!]

(In response to Philip Evans)

Hello – thanks for this. We have the Langbein volume in our reference library at Kew so I will have a look at it. I just looked up Topcliffe in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – what a career!

My ancestor Isabel Rigby of Hindley was sent from a Wigan court to Lancaster, accused of witchcraft. She was hung on Gallows Hill on 10th May 1666 then buried in Saint Marys graveyard. Ive contacted Lancaster archives as regards any possible trial records to try and find out what she was accused of but any other information any records give about her would be much appreciated. Thank you.

This is a really interesting article, the collection of witchcraft books that we put together at The Lost Book Project goes into the history of witchcraft, it’s really fascinating.

Hi Jessica – I am very interested in this particular chapter of the Pendle ‘witch’ history. I wonder if there are any other surviving records you might be able to point me towards? I live in Australia, so unfortunately cannot visit the archives in person (for now!).

Dear Meg,

Thank you for your comment.

You can find the re-examination of Edmund Robinson online, along with a number of other witchcraft-related records you can browse.

You can also find further images and links here.

Oh my goodness, I only just found your reply. Thank you! This is wonderfully helpful!

Hi,

I was wondering if there was any surviving sources that actually detailed the process of the medical examinations of those accused of witchcraft?

Or is the only evidence simply the medical examination certificates?

Very interesting article. However, I am not sure that “no one would have questioned the existence of witches, or the belief that they could use sorcery to cause harm.” In fact, by no means everyone back then believed all this witch nonsense. Reginald Scot wrote eloquently and at length against it, as did several others.