Out of the destruction and chaos of the Western Front during the First World War, emerged an American called Edward Page Gaston, a journalist living in Sutton, England, in the London suburbs.

While working as the European manager for a firm of American publishers, he put himself forward to help the families and friends of British prisoners of war in Germany by offering to convey much-needed money, food and clothes to the prisoners in Germany. He had originally been sent by a Committee of Americans, to Germany, to find their lost luggage. This earned the praise of the American ambassador in London, Walter Page, in October 1914, who stated that he considered Mr Gaston a very trustworthy as well as a very energetic man, in correspondence sent to Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary (FO 383/47 file 38099). He was also recommended by Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War.

Gaston had publicity material printed, which includes photographs of himself. Two examples survive among Foreign Office records.

Gaston was at the forefront of the anti-alcohol Temperance movement, founding the World Prohibition Federation and the International Prohibition Confederation, and later he was national commander of the anti-communist Patriot Guard of America. Additionally, combining his interest in archaeology and self-publicity, he was granted permission to search for the remains of Pocahontas at St Georges Church in Gravesend. His sister, Lucy Page Gaston, was also a prohibitionist, being a zealous anti-tobacco campaigner.

As the war progressed, serious doubts arose about the efficiency and honesty of Gaston. The negative reaction to him resulted in Gaston bringing a libel case in the King’s Bench Division of the High Court in London, in 1915, against five newspapers: the Daily News, the Daily Chronicle, The Globe, the Morning Post and the Manchester Guardian. Gaston’s claim was for damages and an injunction to restrain the defendants from publishing the same or similar libel.

The American ambassador in Berlin, James W Gerard published a notice in the British newspapers entitled Presents for Prisoners, in which he issued a warning against Gaston to friends of prisoners of war in Germany ‘confiding anything in this man. He has no connexion with the Embassy, and I will not even permit him to enter it. He has been required to leave Germany and Belgium by the German authorities. I most earnestly beg the British public and the friends of prisoners to have nothing to do with him.’ The ambassador from the beginning of the war, took responsibility for British interests in Germany and visited and assisted British prisoners of war.

Gaston’s statement of claim, lodged in the King’s Bench Division, said that the defendants falsely and maliciously published the notice and that he, with official sanction, actively engaged in relief and other kindred work, on behalf of British prisoners of war, both wounded and unwounded.

Reports on the libel action are given in The Times newspaper on 2 December 1915, 17 March and 5 April 1916 respectively. The case had been argued in court, including in the Court of Appeal on points of law, as a preliminary to a full trial.

However the judge in the King’s Bench Division concluded that he did not think litigation could be carried on as usual, while there were witnesses who could not return to England and while the country was still at war with Germany. It could only be fairly tried after the war.

Gaston went back to the Court of Appeal in April 1916 to try to reverse this decision but the judges reaffirmed that the American Ambassador in Berlin and others would only be able to appear in court after the war. Gaston, who moved back to America, did not pursue the case after the war and so it never came to trial.

The solicitor representing the newspapers had felt that they would be unable to bear the cost of a trial and that it was right for the government to contribute to any future costs. The Treasury Solicitor, on instructions from the Foreign Office agreed, on certain conditions to pay half the costs but felt that there was little chance that Gaston would succeed in his case.

List of un-traced British prisoners of war and remittances turned over to the American ambassador in Berlin by Gaston (catalogue reference: FO 383/47, file 155735)

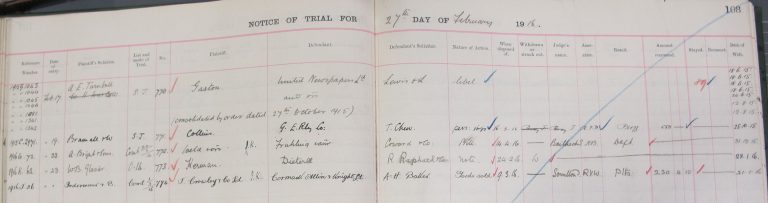

Sadly most of the court records for the libel action have not survived, although there is the Cause Book (J 87/86, notice of trial 27 February 1916), and the judge’s order in the Court of Appeal Order Book for (J 70/15 pages 171-173). However there survives a large amount of Foreign Office correspondence on the libel action and Gaston’s activities in Germany (FO 383/47, FO 383/48. FO 383/50, FO 383/177, FO 383/296).

Gaston is also mentioned in the interviews and reports of the Committee on the Treatment of British Prisoners of War. You can download these records. In WO 161/96/12 near the top of page 594 of the first download, part of an interview in 1914 with the Captain Philip Godsal, who was held in Torgan camp in Germany, remarked that the prisoners believed Gaston was an imposter, and that many parcels sent through him were delayed for months, some for over a year. In WO 161/96/21 on page 664 in the second part of the download, in the interview of Colonel Jackson in 1914, he remarks that Gaston and an official from the American Embassy visited Torgen, and that he told them that none of the letters and parcels had reached the prisoners in the camp.

You can read about the plight of soldiers and their families during the First World War in The Quick and the Dead: Fallen Soldiers and Their families in the Great War, by Richard van Emden, which you can buy online through The National Archives bookshop.