The Zeppelin – named after the major German manufacturer Count Zeppelin – was the size of an ocean liner, twice the size of a jumbo jet (500ft long and 50ft wide) and made of the strong aluminium alloy duralumin. It truly was a sight to be reckoned with.

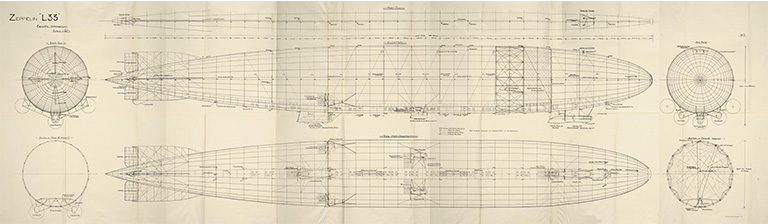

Zeppelin L33, plan A, 1917 (CAT REF: AIR 10/864)

The airship’s first attack on Britain was on the Norfolk town of Great Yarmouth, occurring down the Eastern seaboard from Norfolk to London, followed later by an attack from Hertfordshire to Essex.

Other airships were also used in attacks, including the wooden framed Schutte-Lanz model. By resorting to air attacks, the Germans tried to force an early end to the War; attacking men, women and children, they hoped to break the spirit and morale of the British public.

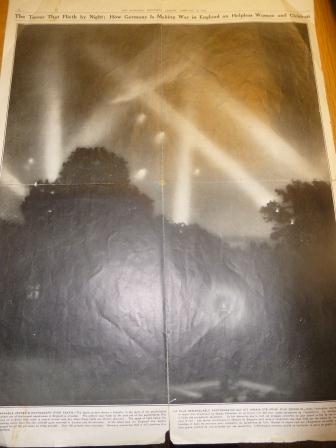

“The terror that flieth by night: How Germany is making War in England on helpless women and children” Report from The Standard, Montreal 12 February 1916. AIR 1/679/21/13/2193

For years the Royal Navy had defended Britain’s shores, but pitted against this enemy – which at 10,000+ feet flew too high to thwart – they were rendered near powerless to attacks.

On the night of 19-20 January 1915 people reported hearing a throbbing sound followed by explosions. Two people lay dead, killed by shrapnel, as Britain’s first air raid casualties.

The only thing we could compare this air raid to is a terrorist bomb. The Zeppelin bombing was unexpected and random – a concept that would seemingly have been terrifying to the general public. Many people in Great Yarmouth didn’t realise how their town changed the history of war. In 1915 many people hadn’t even seen an aeroplane, so a Zeppelin would have equated to something from a science fiction novel.

The Germans government had devised their plan, hoping to create mass panic, destroy the morale and force the British to sue for peace. Yet, unexpectedly, no hysteria broke out – people reacted stoically and calmly.

The air raid was a matter of luck or misfortune as to where the bombs hit, with the attack on Great Yarmouth actually being meant for the Humber area. Often the Zeppelin’s did not know where they were due to poor visibility and strong winds; it was hard navigating and then returning home. Zeppelin pilots often weren’t aware of what they were bombing.

King’s Lynn was attacked next. This time, even more structural damage was caused and a further two civilians lost their lives. The propaganda value was, imaginably, enormous. Britain’s first blitz; one of the first casualties it was reported had only just lost her husband on the battlefield and now she too was dead. The war in its early stages was not going well for Britain, and there was a growing sense of outrage at these wilful and wicked attacks against a defenceless population.

For the next few months Zeppelins would hit towns in the East, Ipswich, Southend and Bury St Edmunds – killing six more people.

Initially the Kaiser banned any bombing of London, specifically on royal palaces and residential areas. But he soon relented and four months after the first attacks the L38 Zeppelin cast its shadow over London. A residential property in Stoke Newington was the first to be hit by an incendiary bomb. The first casualty was a two year old child, henceforth the airships were dubbed the ‘Baby Killers’. 3,000lbs of bombs and 91 incendiaries were dropped on the capital, resulting in over 40 fires and the deaths of seven inhabitants. No shots were fired in retaliation, and no search lights picked up the raiders, but tensions ran high and German businesses were ransacked, with eventually thousands of Germans living in this country being interned.

There was still no mass panic; society didn’t collapse and industry didn’t stop, despite the grim and constant threat. Zeppelins did make quite a spectacle because of their size and they travelled so slowly that if you were underneath them you were relatively safe.

However, as the Zeppelin campaign stepped up the death toll started to climb steadily. By September 1916 the entire capital was open for bombing. September 8 was the most destructive day, with Euston and Liverpool Street stations, Bloomsbury and Holborn all subjected to heavy shelling. Searchlights were picking the craft out and the guns were blazing away but failing to hit their target. Carnage ensued, public buildings were destroyed and homes ripped up. 22 people were dead and 87 left with horrific injuries.

Anger over the air attacks was now being aimed at the Government – why were our defences so inadequate? The best fighting aircraft were reserved for the Western front, which meant Home defence was allocated inadequate machines. They were too slow to climb to the Zeppelins’ altitude in time, whilst their machines guns were like trying to sink a battleship with a pea shooter. Eventually Britain developed specially equipped fighter aircraft, whilst anti-aircraft artillery was introduced, including the advent of mobile guns and also barrage balloons.

Yet the Zeppelins were also advancing technologically; they started using observation cars – winched down from the main craft – which could be used for spotting and also pinpointing ones locations in thick cloud (although this concept might seem quite hairy in light of the fact that anti-aircraft guns could be shooting at the Zeppelins from all angles).

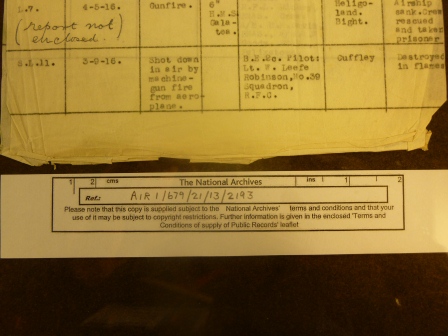

Despite improved defences it would be another year before the tide turned. In early September 1916 a dozen airships headed for Britain (the biggest raid yet); bombs fell in Nottinghamshire, Lincoln and Kent, but only one airship made it to the primary target of London. On 3 September pilot Leefe Robinson became an instant hero, when his aircraft destroyed and crashed a Zeppelin in rural Hertfordshire. He was awarded a VC for the victory.

Entry of the first Airship brought down by Royal Flying Corps – Pilot W. Leefe Robinson, 3 September 1916. AIR 1/679/21/13/2193

The Germans introduced the super-Zeppelin, but its days were numbered. The super-Zeppelin’s Achilles heel was found by shooting explosive and incendiary bullets, which proved its undoing. One was brought down in Essex.

As four more airships were reduced to scrap, it marked the beginning of the end for the Zeppelin as a weapon of war. All in all 500 people had been killed across the country and over 1000 injured. The last ever raid was over the Norfolk coast on 5 August 1918, with the newly formed RAF successfully attacking five Zeppelins.

Zeppelin L15, shot down April 1916 (CAT REF: AIR 1/645/17/122/325)

Looking at the First World War more generally, mortality rates as a result of Zeppelin attacks were relatively low, yet they really illustrate that the war could be and was brought so destructively to the Home front.

Whilst industry didn’t stop munitions factories were targeted and the Government changed the clocks, the much-discussed British Summer Time, to enable young women to get home safely before the Zeppelins came over. The estimates of deaths I have seen are about 530 dead and Woolwich was because of the Royal Arsenal a big target as the Royal Ordnance Factory.

[…] UK National Archives – First World War airship attacks http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/airship-attacks-england-first-world-war/ British Library plans to digitize 11 million old manuscripts […]

ive found tis website very useful towards my knowledge of attacks taken place on Britain by the nazi soldiers

Zeppelin attacks could be compared with the German V weapons aimed at London in 1944, long before terrorists attacks. My mother, living in Tufnell Park, clearly remembered the zeppelin shot down in 1916 that crashed at Cuffley. She told me about this at the time we took to our shelter (under the dining room table!) as we watched ‘buzz-bombs’ flying overhead, waiting for their engines to cut out.

You were safer under the table or under the stairs rather being killed on the way to the flimsy Anderson Shelter in the garden.

I am interested in the history of the Major Oak tree in Nottinghamshire (of Robin Hood fame near Edwinstowe). I have a postcard of the Major Oak which has a message on the back mentioning a raid nearby by a Zeppelin. I can’t read the date fully on the postmark – but in the text it mentions the month of March and snowy weather. I am speaking at a conference with regards to the Major Oak and would love to try to work out the date of the raid, as I think the Zeppelin attack nearby is a really important part of the trees social history. Can you help please?

I think you will find the zeppelin attack of 8/9 Aug 1916 included the premises of Whitley Bay councillor Napp in Whitley Road, the shop, run by his wife, sold vegetables and confectionary.

Many of those who suffered the London Blitz in WW2 had also lived through Zeppelin raids in WW1 losing family members in both conflicts. Perhaps it’s not surprising that the term Greatest Generation refers to these people.

I have been able to discover that my Great uncle PC Thomas Minke aged 35 was fatally injured during a Zeppelin raid on 30 September 1915 serving in the City of London Police.

Hi Alan

Your great uncle, Thomas Minke, was sheltering in Sun Street Passage – between Broad Street and Liverpool Street stations – at around 11.00pm on 8 September 1915, when a bomb exploded. He was taken to St. Bart’s Hospital where he underwent an operation to remove a bomb fragment from the groin area. Unfortunately infection took hold and he died three weeks later.