Many people remember the AIDS health campaign of the 1980s, particularly the powerful and chilling television advertisements with the falling tombstone and John Hurt’s portentous voiceover, and the slogan ‘AIDS – don’t die of ignorance’.

Hysterical reporting

AIDS stands for Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. It is a condition in which a weakened immune system leads to vulnerability to infections; back in the 1980s there was no treatment and no prospect of survival. As Alwyn Turner has written:

‘the first couple of years of the syndrome’s progress in Britain were characterized by some hysterical reporting, with a particular emphasis on the fact that it was primarily gay men who were showing up as being infected. The expression “gay plague” became accepted media shorthand’ [ref] 1. Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s, Alwyn W. Turner, p.220, Aurum, London, 2010. [/ref]

Some people were afraid that you could catch HIV from toilet seats, or from sharing communal baths.

Cutting through prejudice

Norman Fowler (Health Secretary 1981-87) took an evidence-based approach, drawing on advice received from the Chief Medical Officer Sir Donald Acheson. Fowler had to rapidly get ‘up to speed’ on the issues, but once he had done so, he was determined to get accurate information into the public domain, to prevent further spread of the illness; he wanted to cut through the prejudice and push the message that AIDS could affect any sexually active person, regardless of sexuality.

By mid-1985 the extent of the health threat posed by AIDS had moved up the government’s agenda. The pressures for hospitals treating AIDS patients (particularly in the London area) were rapidly increasing. A file (PREM 19/1863), recently released by The National Archives, shows Margaret Thatcher’s administration grappling with the issue, and Mrs Thatcher’s personal reactions to the content of Fowler’s proposed health education campaign.

Debate over language

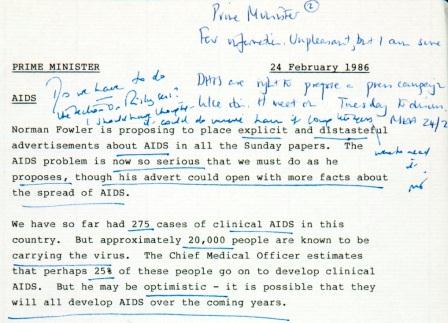

David Willetts (Policy Unit) agreed to the need for the health campaign, but warned the prime minister on 24 February 1986 that Norman Fowler ‘wishes to place explicit and distasteful advertisements about AIDS in all the Sunday papers’.

Thatcher’s concerns focused on the language used to explain about the sexual practices which could lead to HIV infection, specifically unprotected anal sex. When Fowler circulated a memorandum giving details of his planned publicity text, Thatcher wrote: ‘Do we have to have the section on risky sex? I should have thought it could do immense harm if young teenagers were to read it’.

Margaret Thatcher’s annotations regarding proposed newspaper adverts (catalogue reference: PREM 19/1863)

What caused Margaret Thatcher’s reticence? I will leave that to others to judge. The file does show that she took, at least initially, a narrow view about how the audience that the health campaign needed to reach, a view that was at variance with the best medical advice. Nigel Wicks (Principal Private Secretary) wrote that she ‘thinks that the anxiety on the part of parents and many teenagers, who would never be in danger from AIDS, would exceed the good which the advertisement would do’. It can be argued, of course, that it took some time for government ministers to acquire a full understanding of the threat posed by AIDS.

Willie Whitelaw, the Lord President, voiced Thatcher’s concerns at the relevant Health Committee, but the Committee insisted that the material had to be included. Thatcher’s objections continued – at one point she wrote to ask ‘whether a check has been conducted to see that the advertisement does not fall foul of the Obscene Publications Act’. After Fowler agreed a couple of amendments to the adverts, they were duly published.

The debate about the need for straightforward language continued: Lord Hailsham (Lord Chancellor) once described some of the proposed language as ‘sometimes almost ludicrous’. However, the file shows that Fowler, and the medical experts, ultimately won this battle. It also shows that, in the early days, the message was given that anal sex carried the highest risk and should be avoided altogether – this message was soon replaced by exhortations to use condoms for safe sex.

Leaflet drop

Health Education Council AIDS advice leaflet, 1985 (catalogue reference: PREM 19/1863

By August 1986 Norman Fowler wanted to step up the public education campaign. He proposed that an AIDS leaflet be delivered to every household in the UK spelling out in straightforward language what they needed to know. Again, Thatcher voiced objections: ‘why universal delivery of AIDS leaflet – but nothing about drugs? My first reaction is against the idea – but await other comments’.

This comment shows that Thatcher was prepared to listen to other voices before coming to a firm conclusion. Lord Hailsham was also doubtful about the wisdom of the leaflet drop, writing that ‘it might well spread panic’. However, David Willetts urged the government to pursue the issue with the utmost seriousness and proposed that the prime minister hold a review meeting with interested ministers. Bernard Ingham, Chief Press Secretary, argued that the prime minister should be seen to take a personal interest in the issue. On 7 November 1986, Thatcher gave her agreement to the leaflet campaign, which went ahead, accompanied by television advertisements first shown in early 1987.

Some people thought that the dramatic advertisements demonised AIDS still further by adding to fear levels; however, the general consensus among historians and commentators is that the information campaign (which continued until the mid to late 1990s) was successful in raising public awareness and in saving lives. According to a BBC Panorama article, ‘new diagnoses of HIV, which were over 3,000 in 1985, dropped by a third in three years. The number of new diagnoses stayed relatively stable until 1999’.

Norman Fowler is now a tireless campaigner and advocate for people living with HIV and AIDS. He published a book entitled ‘AIDS: Don’t Die of Prejudice’ in June 2014.

On 2 February Matt Cook will be giving a talk at The National Archives, focusing on mass observation and the anti-gay ‘backlash’ of the 1980s: AIDS, the 80s and the fate of permissiveness.

Mark,

Thanks for the interesting article, however to get a clearer picture of how the issues across Government were dealt there are of course quite a few files outside the PREM series including compensation to those who were infected with HIV/AIDS via contaminated bloods, an issue which was again in the news in Parliament in the last few weeks.

David

Thanks for sharing Mark. In the 1980’s the government then could have invested more money in programs that advocate for HIV/AIDS awareness and care. We also have a campaign to transform live at social and health services.

http://www.socialandhealthservices.org/