Although military usage of balloons dated back over a century, the gleaning of intelligence with regard to enemy activities traditionally relied upon scouting and cavalry units. When the newly created Royal Flying Corps (RFC) assumed responsibility for military aviation from the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers in May 1912, enthusiastic RFC officers continued to experiment with aerial observation and photography. However, the latter’s potential was met with varying degrees of scepticism by the British High Command.

With the outbreak of hostilities, early optimism soon vanished in the absence of any quick and decisive breakthrough. The dawning realisation that a protracted conflict on an unprecedented scale was ahead called for new approaches, and gradually an appreciation of the value of aerial photography and its applications would transform the Allied prosecution of the war.

Aerial photograph showing the ‘lunar’ effect of heavy shelling. (catalogue reference: WO 316/13/26)

The first RFC squadrons began to arrive in France in August 1914 and were immediately utilised in observation and reconnaissance duties for ‘target acquisition’. In the field, the inadequacy of the issued mapping, which largely comprised of French maps of Napoleonic origin, was soon apparent. Despite initial resistance from Maps GHQ, vertical aerial photographs, from which direct tracings could be made, quickly proved their worth. They became essential, not only for accurate map making, but also for broader intelligence gathering and tactical briefing.

By the end of the year, the first Photographic Section had been formed as part of 1st Wing.

The work was extremely hazardous even before the presence of the enemy was taken into account.

Initially making use of a Pan-Ross camera with a 6” lens, the aircraft were generally unarmed with the observer leaning over the side of the aircraft, camera in hand and changing plates with frozen fingers at 5,000ft. Officers such as Lieutenant-Colonel JTC Moore-Brabazon led the way.

Germans troops inspect the wreck of Lieutenant Geoffrey Joseph Lightbourne Welsford’s BE 2 near Quesnoy Farm, Pas de Calais. It was shot down on 30 March 1916 whilst engaged in photographic reconnaissance with 15 Squadron (catalogue reference: WO 339/30681)

By early 1915 the improved ‘A’ camera, with an 8¼” or 10” focal length and a 5” x 4” plate, was obtaining good results. Later that summer the ‘C’ type camera, with two magazines containing plates that were semi-automatically changed, allowed a rapid succession of photographs to be obtained.

Recognising the import of aerial photographs was one thing; getting the systems in place on the ground to make effective use of the plates another.

In July 1915 a conference was held at the War Office to address the problems experienced in the field. A School of Photography was established at Farnborough in September 1915 to provide men with the necessary skills in processing and camera maintenance and repair, as well as in map reading and plotting. There was also the new science of interpreting the information contained in aerial photographs, of recognising features and their meaning and what the light and shadow revealed, to which end the insights of officers with a background in archaeology proved invaluable.

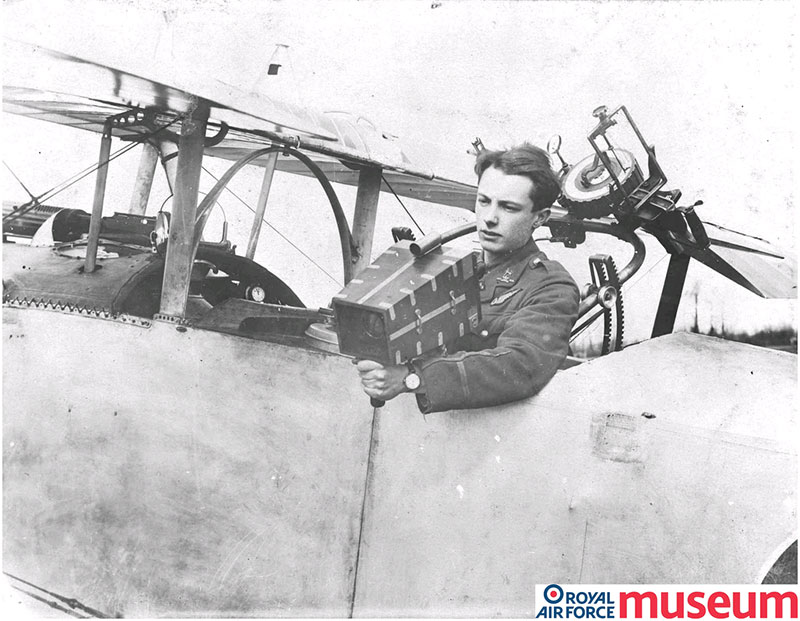

Lieutenant S C Thynne demonstrates the use of a hand-held camera in the back seat of a Nieuport aircraft. Image used with permission of the Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum

By 1916 each Army in the Field had an RFC Brigade divided into a Corps Wing and an Army Wing. Every squadron in the Corps Wing had a photographic section (consisting of one NCO and three men) whilst in the Army Wing only one squadron had a photographic section. Both wings had a Photographic Officer liaising with the General Officer Commanding the Brigade and with Intelligence at Army Headquarters. Usually the Corps Wing undertook all photographic work in the Corps counter battery area and the Army Wing carried out the photographic work required by the Army Staff.

Trials carried out in June 1916 (AIR 1/123/15/40/144) demonstrated that prints could be in the hands of Corps HQ within an hour of the exposure being made:

1st Wing No 2 Squadron 10 June 1916

- 7:50am – aerial photograph taken

- 8:10am – machine landed

- 8:32am – finished print despatched to 1st Corps

- 8:39am – received at 1st Corps Total time: 49 minutes

The required number of photographic prints would then be distributed.

Correspondence drawing on the experience of Lieutenant Danby (AIR 1/899/204/5/752) dated 13 March 1916 concluded that 2,500ft was the lowest limit at which good photographs could be obtained under fire, 6,000ft about the maximum, and 4,000ft the optimum.

Various margin notation systems developed as the war progressed with each print marked to identify; the Squadron number in Arabic numerals, the Wing number represented by the corresponding letter of the alphabet (ie A = 1), the number of the photograph, and the date.

Further information could include the identifying map reference, a letter representing the square on the map, and sub-square number locating the photograph on the map. Height and lens details were also added.

Vertical aerial photograph of German trenches east of Hebuterne taken on 23 November 1916 (catalogue reference: AIR 1/895/204/5/714)

Photograph coding

(top left hand corner of photograph)

5 AE 327 = 5 Squadron 15 Wing photograph No 327

57D K11A = map sheet 57D square K small square 11 quarter A

23 11 16 = 23 November 1916

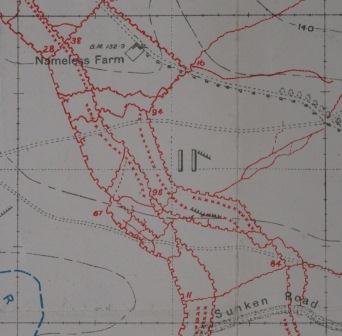

Trench map detail east of Hebuterne (catalogue reference: WO 297/6639)

Trench map

The corresponding square on map sheet 57D showing the German trenches corrected to 19 August 1916. Quarter-square A is the top left quarter. The aerial photograph taken some three months later shows further trench engineering.

Development saw the introduction of semi-automatic cameras and the standard focal length of 8” increased to 20” with 18” x 24” plates in use by the end of the war. As well as vertical views, obliques (angled photographs) proved useful for identifying obstructions when planning advances, especially in regard to tank warfare. The popular Victorian stereoscopic principle was also used, utilising two photographs separated by a slight time delay (and hence taken at slightly different angles) so that when viewed through a stereoscope eye piece it produced the illusion of relief.

A staggering amount of photographic prints were produced during the First World War. Various sources give slightly differing figures but whilst maybe a few hundred aerial photographs had been taken during the opening six months of the war, by 1918 well over five million were produced in just nine months (AIR 1/724/91/2).

| 1918 | Aerial photographs (totals) |

| January | 416,863 |

| February | 366,205 |

| March | 518,343 |

| April | 290,332 |

| May | 872,967 |

| June | 651,210 |

| July | 684,988 |

| August | 827,514 |

| September | 656,404 |

| Total | 5,284,826 |

In post-war Britain returning RAF officers (the RAF was established as a separate arm on 1 April 1918 combining the RFC and Royal Naval Air Service) recognised the civil, scientific and archaeological value of aerial photography and the commercial opportunities it offered. Subsequently a number of companies were established, notably the pioneering air survey company Aerofilms Ltd (see the britainfromabove.org.uk website).

The German Guard of Honour for Lieutenant Geoffrey Joseph Lightbourne Welsford, his coffin being borne on the left (catalogue reference: WO 339/30681)

It is very rare to find photographs within the records and correspondence for Regular Army and Emergency Reserve officers. However, three photographs can be found in the file of Lieutenant Geoffrey Joseph Lightbourne Welsford RFC, killed whilst undertaking photographic reconnaissance duties. A German message was later dropped behind British lines that included a letter penned by Welsford’s observer Lieutenant W Joyce who survived the crash:

‘…this morning we were shot down at 6,000ft. Welsford was shot dead in the air. I managed to climb to the back seat and get partial control at about 300ft. I could not get at the rudder bar and we crashed’ (AIR 1/689/21/20/15).

An only son, Lieutenant Welsford was 20 years old when he died leaving behind his wife and widowed mother. He is now buried at the British Cemetery at Fillievres.

Photographs can be found throughout the papers of the Air Historical Branch in the AIR 1 record series (many remain un-catalogued) along with written reports, recollections, and papers on the development of aerial photography. Aerial photographs of the Western Front can be found in the WO 316 record series; Gallipoli in the WO 317 record series; Salonika in the WO 153 record series; Palestine in the WO 319 record series.

Further reading:

Shooting The Front, Terrence J Finnegan: Spellmount (The History Press) 2011

Cross & Cockade International – the excellent quarterly journal of the First World War Aviation Historical Society – for all aspects of First World War aviation: www.crossandcockade.com

Dear Sir,

I’m searching for aerial photographs of Middelburg/ East Flanders in Belgium. Can you help me with a reference who can tell me where to find photographs?

Hi Thomas,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

[…] photo-reconnaissance was first widely used during World War I, substantial clandestine peacetime photo-reconnaissance was first carried out in the 1930s. […]

Hello , I am searching for information about William Henri Robson, who was an areal photographer during WW1. Can anyone help me please. Thanks in advance, Huguette