Ada Lovelace, portrait by Alfred Edward Chalon (1838) . Under Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ada_Lovelace_portrait.jpg

Ada Lovelace day is an opportunity to celebrate women in science, technology, engineering and maths, both historically and currently.

Ada is now widely believed to be the world’s first computer programmer due to her notes on the first algorithm carried out by a machine. However, at the time her work was largely overshadowed by her-well renowned friend and colleague Charles Babbage, who is credited with creating the world’s first computer.

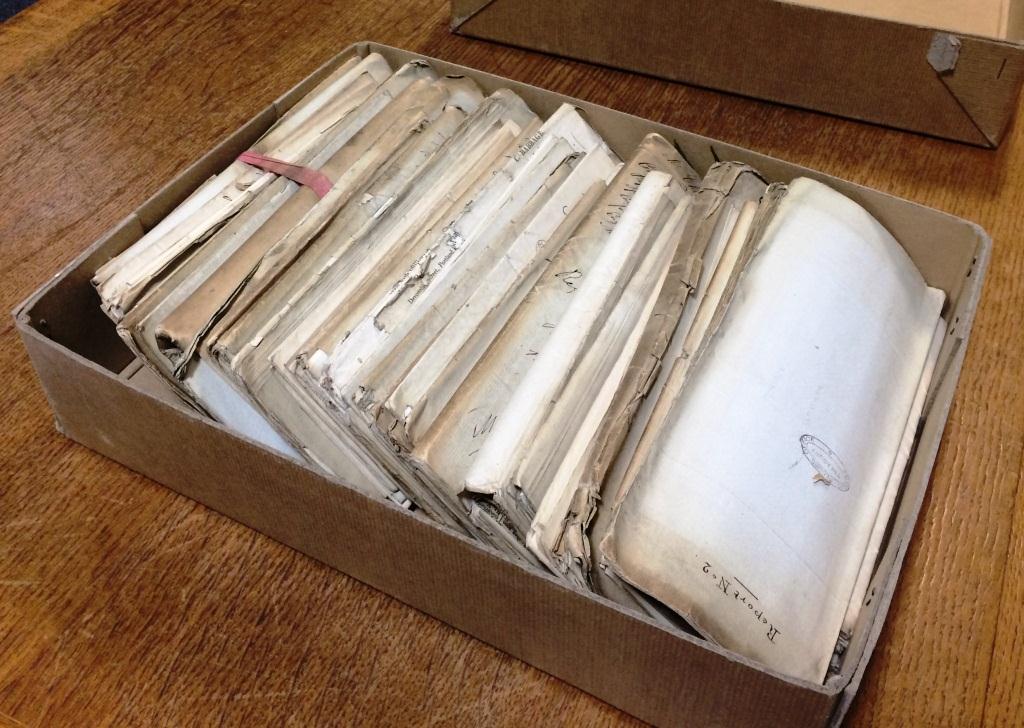

Typically, in our collection we hold documents relating to Charles, but not on Ada. But a little searching on Discovery, our catalogue, reveals that we hold many documents relating to women in science, from some of the early pioneers in women’s medical schools to the nurse and statistician Florence Nightingale.

To highlight forgotten women in science I have been looking through Ministry of Health records and those of the Medical Research Council.

I stumbled across examples of early twentieth century concerns about maternity and child welfare. The document FD 1/3757 illustrates the findings of Dr Evelyn Hewer, of the London School of Medicine for Women. In 1919 she started researching feeding patterns of mothers, using charts and questionnaires to compare feeding methods and the length of children’s lives.

The file is full of women working on the project as assistants, professors or doctors. However, typically for documents relating to women’s work at this time, the file is littered with comments on women’s ability to work. One example is of a Miss Kathleen Ford, and it is repeatedly noted she is a ‘thoroughly trained and competent worker’ (FD 1/3757 ).

Among the file are many letters concerning the Child Life Investigation Committee from Winifred C. Cullis, the first woman to hold a professorial chair at a medical school, becoming professor of physiology at the University of London in 1919.

This involvement of professional women in child and women’s welfare may seem to still confine women to traditional roles. However this was a very important time in these areas with significant legislation such as the Maternity and Child Welfare Act 1918. Women’s welfare centres became commonplace, with 1,525 in existence by 1918. They offered antenatal services and, often controversially, birth control advice, in a time before the National Health Service. [ref] 1. Gisela Bock, Patricia Thane, Maternity and Gender Policies: Women and the Rise of the European Welfare States, 18802-1950s, p. 107. [/ref]

This is just one area in which women were making headway in early twentieth century medical science, but there are so many more to be discovered too. So today’s post is really a call to urge you to research women in science in our collections – the results can be exciting and surprising! And if you do discover something, please share what you find in the comments below.

Thank you for the article about women scientists. It is interesting that as a teacher-librarian in the 1980s and 1990s I had to ‘dig’ to get any information about women mathematicians for a mathematics project for students in secondary school. I remember discovering all about Ada Lovelace and was amazed about her work and so were the girls who discovered all about her. So often women’s work was published under the name of a man – usually her father, brother, etc. The girls noted this and wrote about it in their biographies…it was very enlightening for them.

Another lady who put down by men was Mary Anning almost all of her work was claimed by men Ada Lovelace was a society lady with prominent friends and relations whilst Mary Anning was fighting to keep her family alive. They have both given a great deal of knowledge to science with little recognition their intelligence was overlooked as ladies could not understand the ways of the world as their brains were too small to understand the ways of the world. Well done them