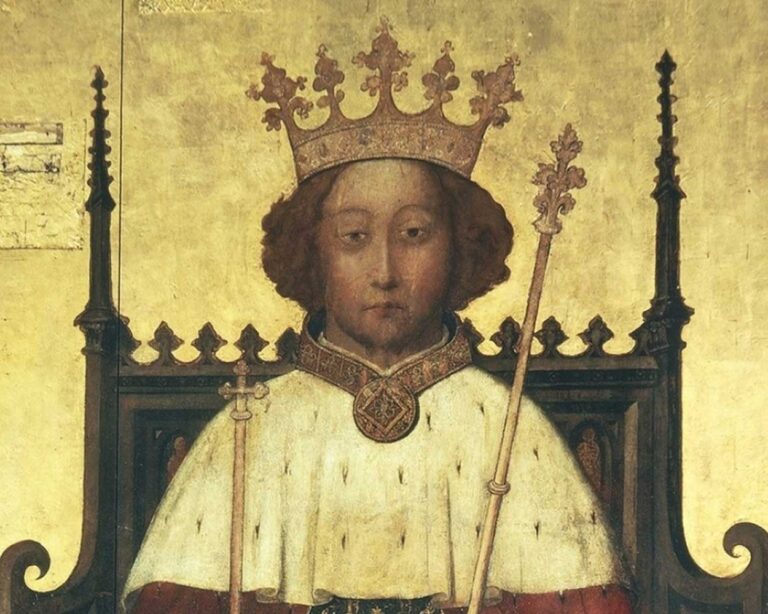

1380s London was characterised by dissent and turmoil, with two warring factions vying for civic power and rule of the City. These fighting sides were led by two Mayors of London, John of Northampton and Nicholas Brembre, and it is the latter whose story and treasonous end will be the focus of this blog.

Northampton and Brembre had very different ideas about how London should be ruled. Northampton used his position as Mayor of London to alleviate the problems of less prosperous Londoners, including some of the City’s lesser guilds, whereas Brembre has traditionally been viewed as a ruthless ruler.

An evil counsellor?

Brembre was a man interested in being part of a powerful network of people that held the monopoly on the wool trade. More importantly, whilst Northampton certainly made use of the Crown’s favour to improve the lives of Londoners, Brembre was a close ally of Richard II, and it was this allyship and his reputation as an ‘evil’ counsellor to the king that contributed to his undoing.

Although his story can be followed in London’s medieval civic records held at the London Metropolitan Archives, there are key records of medieval government at The National Archives, which form a crucial part of Brembre’s story. These records allow us to understand how he came to his demise in February 1388 and how his accroachment of Richard II’s power – ie acting as if he himself held the authority and majesty of the king, when he did not – was considered as treasonous behaviour by his contemporaries.

The beginnings of Brembre’s downfall

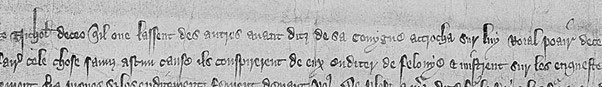

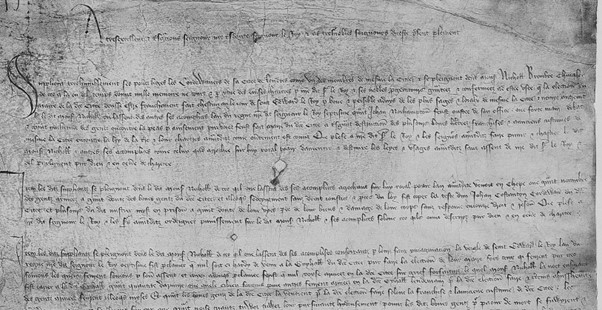

15 petitions were submitted by London’s artisanal community to the Merciless Parliament of 1388. Except for the Tailors’ Petition (C 49/10/3), these petitions form part of The National Archives’ Ancient Petitions series (SC 8). They were produced following a meeting between members of London’s artisanal guilds and the Lords Appellant – Thomas Woodstock, duke of Gloucester; Henry Bolingbroke, earl of Derby; Richard FitzAlan, earl of Arundel; Thomas Beauchamp, earl of Warwick; and Thomas Mowbray, earl of Nottingham – on 18 January 1388.

The Lords Appellant felt that by the end of 1387, the realm was being badly governed and the artisanal guilds, after feeling like they were the victims of Brembre’s corrupt practices and misrule of London, were more than happy to help bring about Brembre’s undoing. These petitions are therefore excellent examples that give an insight into the personal circumstances of those who experienced the turbulence of London, giving them a voice to show how and why they believed that Brembre committed treason against the king by abusing royal power to achieve his own selfish ends.

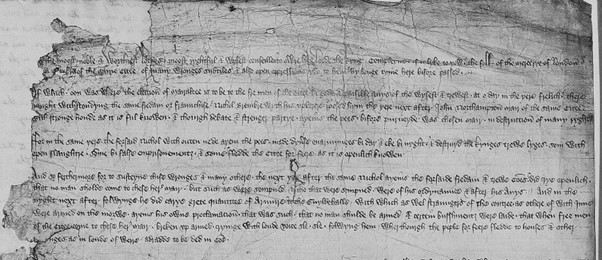

Nicholas Brembre, falseknight of London, by the said accroachment took certain persons from the prison of Newgate by night … and led them out of London to Kent, to a place called the ‘Foul Oak’, and there, accroaching to himself royal power as a traitor to the king, without warrant and process of law he caused them all to be beheaded

Charges brought against Nicholas Brembre, 1388. Catalogue ref: C 65/47

The most heinous crime

The petitions highlight various grievances that London’s artisanal guilds had against Brembre and a prominent complaint that was repeated in all 15 petitions was that Brembre had accroached the king’s power. The petitions therefore mirrored the complaint that the Lords Appellant had made, for the accusation of accroaching royal power featured heavily in the Appeal for Treason. What this means is that the king’s royal power had been diminished.

In the medieval period, kings were seen as being at the top of society, ruling with God-given power, so it was unacceptable that anyone else try to take his power away and use it for themselves. In fact, the act of accroaching royal power was the most ‘hautes tresons’ during the proceedings of the Merciless Parliament, emphasising that it was a treason of the highest order and the most heinous crime against Richard II.

Adapting the allegation of accroaching royal power

The complaint that Brembre, as well as the four other Appellees – Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, Michael de la Pole, earl of Suffolk and Chancellor, Robert Tresilian, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, and Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford – had accroached royal power also featured heavily in the Parliament roll reflecting the proceedings of the Merciless Parliament. What is special about the Guild Petitions, though, was that they made this complaint specific to the City of London.

The allegation of accroaching royal power was usually a royal or baronial accusation, for it had been used several times in the past – for example, during the Parliament in which Piers Gaveston was tried – but the guildsmen adapted it to their context to effectively argue their case against Brembre.

What the guildsmen did was equate the accroachment of royal power with the ruin of good governance and the destruction of rules that benefited the profit of the City of London. In their eyes, Brembre left London bereft of any form of moral conduct or good governance. He was the very opposite of what a good leader looked like.

His bad leadership was referred to across several petitions, such as the Goldsmiths’ Petition, the Cordwainers’ Petition, the Armourers’ Petition, the Saddlers’ Petition, and the Painters’ Petition. They described how Brembre had impinged on life in areas such as Cheapside, where he accroached royal power to himself by coming into the area with a great number of armed men, causing the great fear of all the good men of London (see footnote 1).

The Painters’ Petition and Leathersellers and Whittawyers’ Petition go one step further and emphasised how in doing this Brembre had further accroached royal power to himself by imprisoning many men of the City of London without the judgement of the law (see footnote 2). In fact the Leathersellers and Whittawyers made their complaint even more specific and argued that it was indeed many men belonging to the ‘mestiers’ of the City of London, meaning the men who were a part of London’s guild community, whose rights had been infringed by Brembre abusing royal power.

London’s artisanal guilds also stressed that in accroaching royal power to himself, Brembre had acted without the judgement of the law (see footnote 3). As mayor, Brembre not only made the law but was also supposed to uphold the rule of law and serve as an example. In their petition, however, the guildsmen created an alternative story, one in which Brembre had used royal power to subvert civic life.

The murder of John Constantyn

Throughout their petitions, the guildsmen adopted and adapted the language and arguments used by the Lords Appellant to make their grievances specific to a London context. This was even the case when discussing the horrifying murder of John Constantyn, a cordwainer who was executed in 1384 in Cheapside because he revolted against what he believed to be Brembre’s injustices.

At the time of Constantyn’s murder, Brembre portrayed himself as a mayor who acted to strengthen the governance of London and suppress anyone who dared cause havoc in London, yet we see that in the Saddlers’ Petition and the Cordwainers’ Petition an alternative story is told. For the Saddlers and the Cordwainers, Brembre had only been able to do this and execute Constantyn because of accroaching royal power to himself (see footnote 4).

Even those who had showed loyalty met their ends at Brembre’s hands because of how he had used Richard II’s royal power for his own selfish means. As argued within the Embroiderers’ Petition, even individuals who were ‘so bold as to offer the proof for his loyalty’ were imprisoned and treated with contempt (see footnote 5).

He was a man bereft of any obligation to those who lived in London and, thus, someone who the guildsmen portrayed as a man far removed from having the accepted principles and behaviours of a Mayor of London. He was viewed as having abused his rights and powers as mayor, subverting the traditional power dynamic between mayor and king as a way of enforcing his authority.

A clear act of treason

The guildsmen forged a scenario in which by accroaching the king’s power, Brembre silenced his opponents, with the implication being that Brembre used the king’s powers to serve his own self-interest. What Brembre did, in their eyes, was a clear act of treason. Brembre had subverted the traditional relationship between that of the king and those who served him.

Richard II’s rights were a prominent feature of the petitions, and the guildsmen were echoing medieval beliefs in kingship, for we see these ideas in poems such as Lak of Steadfastness by Geoffrey Chaucer, who described that a strong medieval king was to:

[c]herish thy folk and hate extorcioun.

Suffre nothing that may be reprevable

To thyn estat don in thy regioun

Lak of Steadfastness, 23-25

A medieval king was not to tolerate any behaviour that could be damaging to the realm, and his royal power was to not be abused in any way (see footnote 6).

It’s of no surprise that the phrase ‘encontre la corone’ (‘against the crown’) and ‘encontre ley et la corone’ (‘against the law and crown’) are found throughout this group of petitions. The guildsmen were arguing that in committing his crimes, Brembre was guilty of treason by going against the Crown and the law of the land.

Brembre’s end

The impact of the Guild Petitions in the overall proceedings of the Merciless Parliament was questioned by contemporary writers. The author of the Westminster Chronicle, for example, gives them minimal importance in orchestrating Brembre’s downfall (see footnote 7). In contrast, the political pamphleteer Thomas Favent offers a very different portrayal, praising the efforts of the guildsmen in their endeavour to challenge the corruption of Brembre (see footnote 8).

Regardless, what these records show us is how treasonous behaviour was understood in the medieval world and how a group of individuals could come together to frame their arguments to demonstrate how the treasonous crime of accroaching royal power could be applied in an urban context.

In the end, the Merciless Parliament condemned Brembre for his wrongdoings, and he was executed on 20 February 1388. He was a man who may have considered himself as ‘king within London’ but, by the time of his execution, he was widely viewed as a man without scruples, who even his closest supporters had abandoned. In his final months, he was isolated by friends and foes. Having reached the pinnacle of power, Brembre ultimately fell from grace and was accused of the worst of crimes, treason.

Dr Daniella Marie Gonzalez is a medievalist working in the archive and heritage sector. Her research focuses on discourse, notably the concept of common profit, and political language in late medieval London. Twitter @DeeGonz92

You can find out more about the stories touched on in this blog in our exhibition Treason: People, Power & Plot, which runs until 6 April 2023, where you can view the following documents and many more:

- The 1352 Treason Act

- Inventory of goods forfeited by the Appellees in 1388

- Records of Richard II’s ‘Revenge Parliament’ against the Lords Appellant

You can also read more about Richard II and treason in our book, A History of Treason, available to purchase now from our online shop and all good booksellers.

Footnotes

- TNA, SC 8/21/1004 (The Painters’ Petition); SC 8/21/1005 (The Armourers’ Petition); SC 8/20/998 (The Cordwainers’ Petition); SC 8/198/9882 (The Goldsmiths’ Petition); SC 8/20/999 (The Saddlers’ Petition).

- SC 8/21/1004 (The Painters’ Petition); SC 8/20/1001B (The Leathersellers and Whittawyers’ Petition).

- SC 8/21/1003 (The Pinners’ Petition); SC 8/21/1002 (The Founders’ Petition); SC 8/94/4664 (The Drapers’ Petition); SC 8/21/1004 (The Painters’ Petition); SC 8/21/1005 (The Armourers’ Petition).

- SC 8/20/999 (The Saddlers’ Petition); SC 8/20/998 (The Cordwainers’ Petition).

- SC 8/20/1000 (The Embroiderers’ Petition).

- Marion Turner, ‘Politics and London Life’ in A Concise Companion to Chaucer ed. Corinne Saunders (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), p. 15.

- The Westminster Chronicle 1381-1394 ed. L. C. Hector and Barbara F. Harvey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), pp. 234-37.

- Thomas Favent, ‘History or Narration Concerning the Manner and Form of the Miraculous Parliament at Westminster in the Year 1386, in the Tenth Year of the Reign of Richard the Second after the Conquest, Declared by Thomas Favent, Clerk’ trans. Andrew Galloway in The Letter of the Law: Legal Practice and Literary Production in Medieval England ed. Emily Steiner and Candace Barrington (London: Cornell University Press, 2002), p. 245.

The mention of Henry Bolingbrook, in a position of power, I found interesting. From this position I would be interested to know more on the reasons for his fall from grace during the reign of Richard !!?