Among the records of Prisoners of War (PoWs) during the Second World War held at The National Archives are accounts from Allied PoWs who escaped, evaded, or were liberated from Germany and Italy. Volunteers have been cataloguing the reports in Series WO 208 so that they can be searched by name.

In the course of her volunteer work, Katrina Lidbetter found some fascinating stories about PoWs’ experiences in Italy after the armistice of 1943, which she wrote a blog about last year. She now has further stories to share – this time focused on PoWs’ attempts to escape captivity.

– Keith Mitchell, Volunteers Project Officer, The National Archives

An – impregnable? – three-storey castle

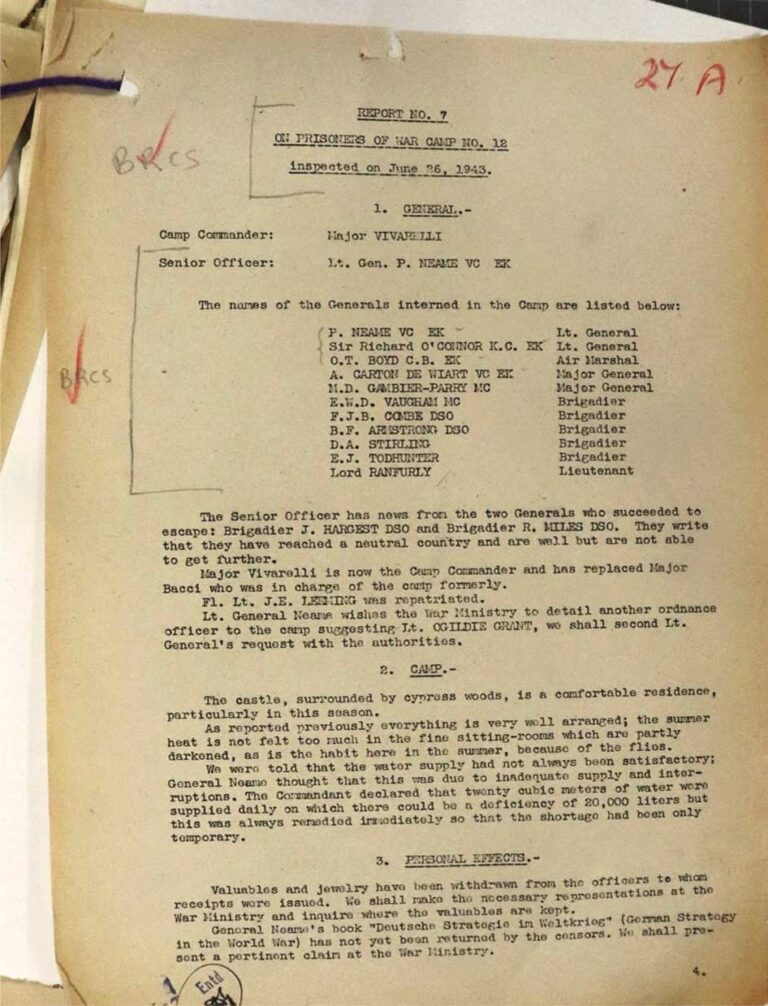

Amongst the WO 208 records are tales from the Castello di Vincigliata near Florence in Northern Italy. This lofty medieval castle was designated by the Italians as Campo Prigione di Guerra 12 – PoW Camp 12. It held some of the most senior Allied prisoners. The stories of those who escaped from it across war-torn Italy are just as astounding as those from the more famous Colditz Castle, which housed prominent PoWs in Germany.

As battle raged back and forth across the North African desert, its rapid ebb and flow led to the capture of some of the most senior Allied officers, including generals. It was a matter of pride to the Italians that they, not the Germans, should hold these senior officers, even though several of them had been caught by Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

They were taken first to the Villa Orsini at Sulmona. They were already planning to escape, but then heard that they were to be moved nearer Switzerland. In September 1941, they were moved further north but to an apparently impregnable three-storey castle, Vincigliata. Lord Ranfurly, one of the PoWs, described it in a letter to his wife as: ‘an old castle restored in the worst Victorian style, grey and featureless with enormous battlements and a tower… the whole surrounded by a high thick wall which one can only see over from the upper windows.’(To War with Whitaker, 1994).

This did not prevent the officers from immediately planning an escape. An abortive attempt to scale the walls out of sight of the guards put the sentries on their guard. Up till then, the Italians had assumed that senior officers would not stoop to breaking out. How wrong they were!

A successful attempt

Having given up the idea of escaping over the walls, the next attempt was to dig a tunnel leading from a sealed chapel. Work started in September 1942 and after six months of painstaking effort, resulted in the only successful break-out, indeed one of very few successful escapes from any Italian PoW camp before the Armistice.

On the night of 30 March 1943, the escapees placed dummies in their beds so they wouldn’t be missed on the night search, and used their tunnel to take flight. With six officers on the run – Generals Carton de Wiart and O’Connor, Air Marshall Boyd, and Brigadiers Combe, Hargest and Miles – this was nearly half of the officers in the castle. In percentages, truly a mass break-out.

The officers paired up. New Zealand Brigadiers Hargest and Miles, dressed as workmen, travelled by the early train from Florence station to Milan.1 Also travelling by train were Boyd and Combe. At Milan Station, however, Combe was spotted and picked up by police. As he explains in his report, to give the others a chance, Combe bravely held out against questioning for two days and was sent to the grim San Vittorio civilian prison before admitting he was a PoW.

Boyd, now alone, got away from Milan but was picked up trying to cross the border. Carton de Wiart and O’Connor who had attempted to walk all the way to Switzerland, were also captured. As the elderly de Wiart had an eye patch and a missing hand, it was amazing they had evaded capture for so long. Meanwhile Hargest and Miles successfully changed trains at Como and then took the road towards the border near Chiasso. Before the town, they cut across country, reaching the border overnight, cut the wire and made it into Switzerland, surrendering to the Swiss police on 1 April 1943 – surely an auspicious day.

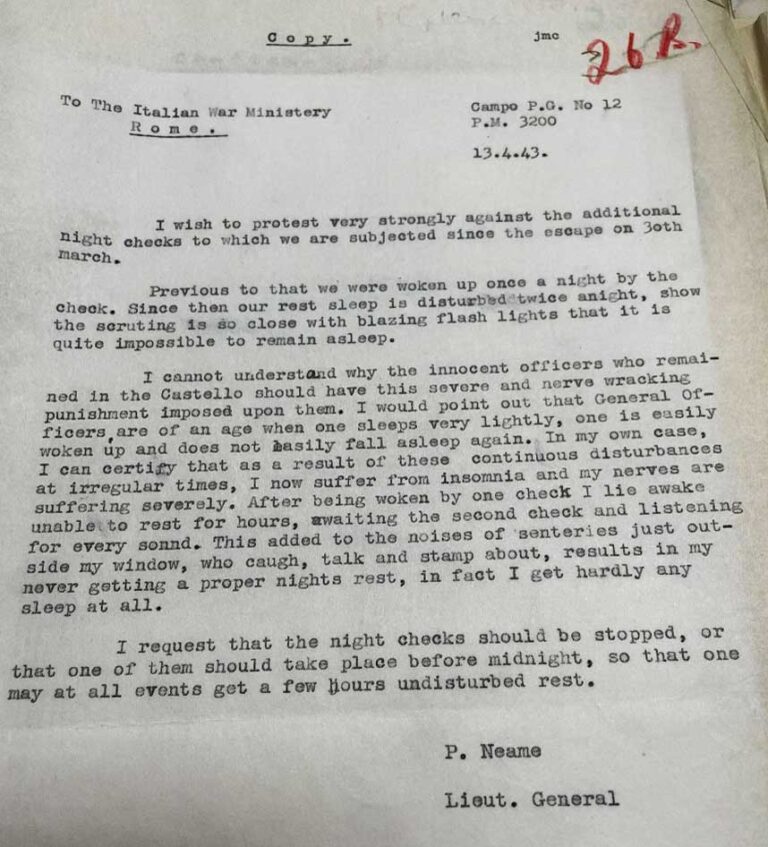

Meanwhile, General Neame, the British Senior Officer, penned yet another complaint to the authorities about night searches being more intense since the escape!

A closing window to leave

Had they only known it, there was no need to escape any more, because in 1943, Mussolini was deposed, and the new government decided to pull out of the war. Unfortunately, the Germans were quick to exploit the confusion in Italy to strengthen their positions, so that by the time of the formal Italian armistice in early September, the window of opportunity for successful evasion across Italy was closing fast.

First to depart was General De Wiart. On 19 August 1943, the Italians gave him a civilian suit and sent him secretly via Rome to Lisbon to negotiate peace terms. He then returned to the UK but was posted to Chungking (now Chongqing) in Free China: stopping over in Cairo in October, he met Lady Ranfurly and gave her his news.2

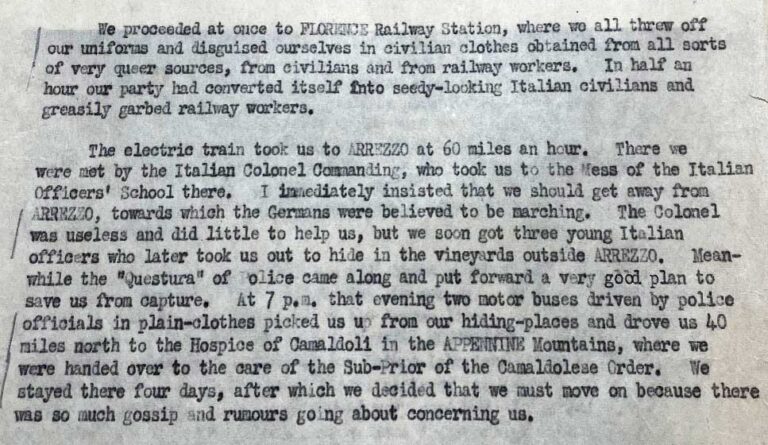

When the Armistice was formally announced, the prisoners donned civilian clothing and the Italians moved them by train to Arezzo. Helped by Italian officers and police, they hid in local vineyards and were then bussed up into the Apennine Hills to be sheltered in a couple of monasteries and local villages. Neame had a secret store of lira which he used to help support the many PoWs hiding nearby.

In Eremo Monastery, Lord Ranfurly fell ill and was given room with a fire and proper bed. While there, he met Richard Carver, Montgomery’s stepson, and Colonel Tony Macdonnell, on the run from Fontanellato PoW Camp. Richard and Tony were given an unheated cell, and although very grateful, they muttered privately about the Monastery’s fine sense of the British aristocracy!3

Alas the Germans got wind of their hiding places. The Generals and their entourage had to split up and flee in the dark and rain. After they left, Eremo monastery literally entombed the personal effects that the Generals were unable to carry with them and they were never found by the Germans. They cycled to Pesaro (once even directed by a German non-commissioned officer who didn’t know who they were).

In one day, they walked twenty miles over mountains and then did a 75-mile bike ride, a stupendous feat for men in their fifties. They rowed out to sea to meet a ship which did not arrive. In November they cycled a further 35 miles. In total they made six unsuccessful attempts to rendezvous with a boat, a huge risk each time, especially for their Italian helpers who risked death. Finally on night of 17/18 December 1943, Neame, Boyd and O’Connor were smuggled to the coast in a taxi and hidden in the hold of an Italian fishing boat. The captain had agreed to take them for a sum of money. As General Neame detailed in his report, the ship sailed through very rough seas to Allied lines at Termoli.

General Gambier-Perry, another Vincigliata PoW, took a different route out. He was helped by Italians to seek refuge in the Vatican, where he was hidden by sympathetic priests.4 Meanwhile Brigadiers Armstrong, Stirling, Vaughan, Todhunter, Combe and Lord Ranfurly were still in hiding near the coast, moving from place to place, with their brave Italian helpers playing a deathly game of hide and seek against the Germans. It was May 1944, after several failed attempts, before they managed to get boats to safety. You can read about their successful evasion and the brave Italians who helped them – as well as Gambier-Perry going underground in Rome – in WO 208/3484.

In modern times Vincigliata Castle has been restored and used as a wedding venue – very different from the gloomy wartime prison.

- A brief account of this escape is in WO 373/62/567 and a longer report on WO 208/3316/1587. A fuller account can be read in Mark Felton, Castle of the Eagles: escape from Mussolini’s Colditz (2017). See also Escape from Italy, 1943-45 by Malcolm Tudor, 2003. ↩︎

- See p.195 of ‘To War with Whitaker’. See also Sir Adrian Carton De Wiart’s biography from the Royal Dragoon Guards Museum ↩︎

- See WO 208/5399/4 and WO 373/94/440 for Carver and Macdonnell’s escape from Fontanellato PoW Camp. More detail can be found in ‘Where the Hell Have You Been?’ by Tom Carver, 2009. (see p.177 for their encounter with Lord Ranfurly). ↩︎

- See Escape from Italy, 1943-45, pages 41 and 81, by Malcolm Tudor, 2003. ↩︎