There are millions of stories, both personal and political, buried inside the hundreds of kilometres of files and documents held at The National Archives. The key to discovering and recovering these stories is a search of our catalogue, known, appropriately, as Discovery. Discovery is at the heart of almost all research here and the best way to determine what we hold. It lists, in wildly varying degrees of detail, all the millions of records that we hold.

The catalogue is not static – we are enhancing it all the time to make information easier to locate. Projects are undertaken all the time to expand the descriptions and details we provide for documents, hopefully raising the chances of a successful match following keyword searches – the first step on many research journeys. These cataloguing projects involve close examination of the records. It is rarely possible to duplicate completely the text of a record, but we can try to improve identification by selecting key details to add into the catalogue description.

When you are working on a project to catalogue records that contain details of very large number of individuals, inevitably you come across some interesting cases. The tantalising snippets of people’s lives laid out on the page often make it hard to stay focused on the project, such is the temptation to chase after the rest of the story as a piece of it passes before you.

This is exactly what has happened to me during my work on a current project to open up the German-created prisoner of war record cards (WO 416) described in a previous blog here. To date, with the dedication and support of 25 volunteers, we have catalogued more than 120,000 individuals on this project, with over 98,000 of these being made openly available for research. Within these we have found heroes, traitors, spies, unexpected numbers of civilians (including women) and stories crying out for investigation, worthy of years of research.

Every one of these individuals will, of course, have their own story, but the unfortunate truth is that it is the records that survive that will dictate how easy or hard it will be to uncover that story. Often, to reveal the fullest picture possible it is necessary to use multiple sources, some held by The National Archives but others held elsewhere. Much of what survives may only exist in the memories of loved ones, colleagues or other parties involved in the story.

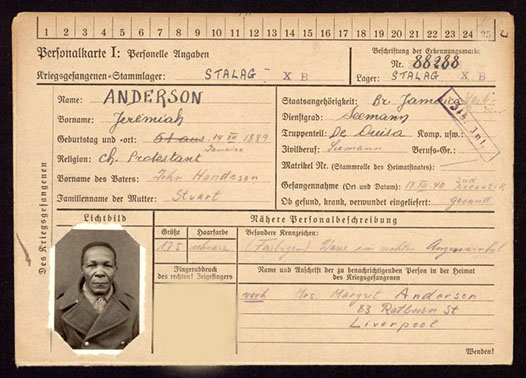

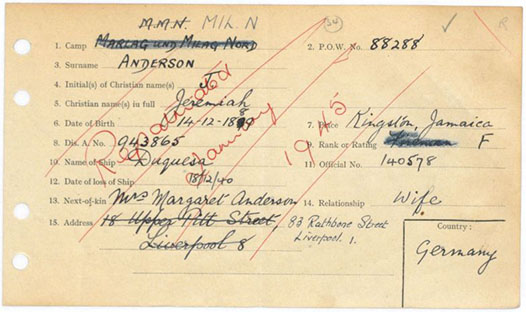

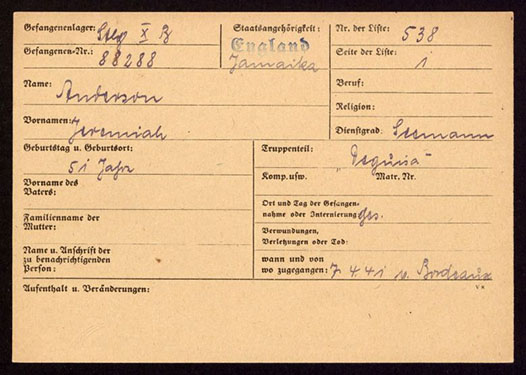

The individual who captured my imagination on this project is called Jeremiah Anderson, a merchant seaman. I am not sure exactly what made him stand out to me, but I think as much as anything it was just how he looked in his photograph. Many men’s photographs appear to show any of a range of emotions from angry at being captured to happy to be alive, but in his photograph he looks more calm and focused. I adopted Jeremiah’s story because of how he came across in his photograph but also because of what I was subsequently able to find out about him across the records, unfurling a story that, it felt, had been waiting 75 years to be told. His POW records are in WO 416/7/200 and WO 416/407/26.

We can link many of these POW records – particularly for the heroes, traitors and spies – to other records held by The National Archives. Fortunately for my interest in Jeremiah, among the most detailed records that we can link to, and one of the largest sets, are those of merchant seamen. We hold Merchant Navy service records and numerous other series of records for merchant seamen serving during the Second World War. For those who were in the military, their service records, to date, remain with the Ministry of Defence.

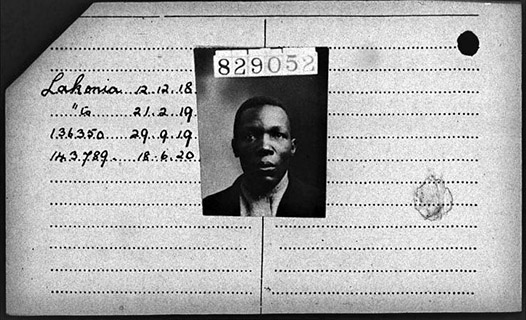

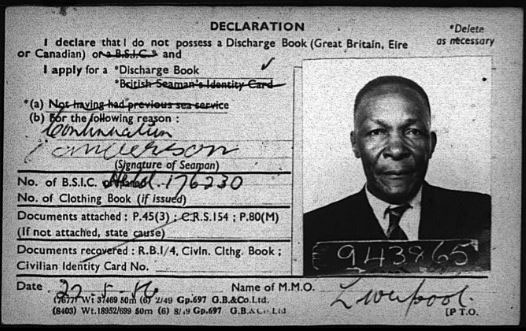

Once I started digging for other records, Jeremiah Anderson’s photograph became a more significant factor in unifying what I found. His records actually extend beyond the Second World War, both back to the First World War and forwards towards the end of his career after the war. Across his recorded career the same focused face crops up several times, in 1918, 1940 and 1950.

The sense I get is that merchant seamen are a less well-recognised part of the prisoner of war story. Many were captured throughout the war, often in far-flung corners of the world, before being brought to camps in Europe for captivity. Some were captured by raid ships seeking cargo such as oil; many were captured as survivors of ships attacked and sunk.

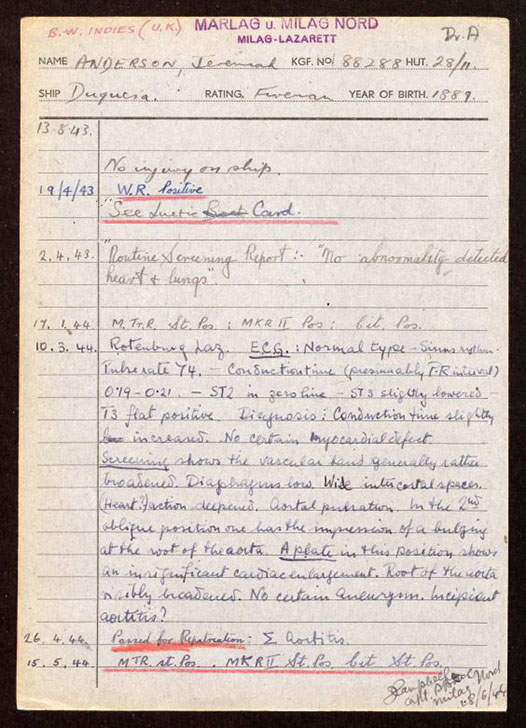

Working through the boxes of POW records it became apparent that, for each merchant seaman among the prisoners, there was a good chance that there would be two separate records. One would be in the main set of alphabetically arranged boxes and another in a set of special boxes holding cards linked to the medical status of some of the prisoners.

This medical form is believed to have formed part of an assessment made by the Germans about which men they were willing to exchange for prisoners held by Britain. Those not fit to work would be more readily exchangeable.

Merchant seamen, as civilians, were also more exchangeable, compared to military men. Jeremiah Anderson was one such man and was repatriated to the United Kingdom in January 1945, based in part on an assessment of his cardiovascular health when he was passed as suitable for repatriation in April 1944 due to aortitis, as detailed in WO 416/407/26.

These records, and others found online, revealed that Jeremiah was a migrant from Jamaica who settled in England many decades before the Windrush Generation of the 1950s and 1960s, whose story we more commonly associate with Jamaican immigration to the UK.

Born in 1889, it is unclear from my research when he came to England, but he was living in Liverpool by the end of the First World War and had married Margaret Ann O’Shaughnessy there in May 1918.

I found records for Jeremiah in BT 350, which is like an identity card from around 1918; BT 364, which is an accumulation of various card types from across his career, and further records showing the issue of campaign medals for service in the First World War (BT 351/1/3108 Index of First World War Mercantile Marine Medals and the British War Medal).

The medal card shows his address as 18 Upper Pitt Street, Liverpool, when they were issued in August 1919. Margaret’s home at the time of their marriage was also Upper Pitt Street, but the number is not given on the marriage record so I can only speculate that they remained in what had been her home. This street was at the heart of Liverpool’s Chinatown but was also a magnet for seamen from across the world due to its closeness to the docks.

They were still living at 18 Upper Pitt Street in September 1939, when the 1939 Register was created for the issue of war-time identity cards and ration books. This address also appears on merchant navy records created in the early 1940s, around the time of his capture, found in BT 382/28 (his service record) and BT 382/3232 (a record sheet recording his capture), before being updated to a new address.

The area around Pitt Street was badly bombed in 1941, which may explain why Margaret is recorded at a new address in Jeremiah’s prisoner of war and service records; this new address at 83 Rathbone Street is consistently seen in records through to 1955. It is only a short distance from the old address in an area now redeveloped next to Liverpool Cathedral.

He does not have appear to have been issued with medals for the Second World War (BT 395), but some of the qualifying criteria for these medals could exclude those captured early in the war due to nothing other than failing to meet a minimum time at sea.

The records located in BT 364 show that Jeremiah Anderson joined the Duquesa on 8 June 1940 and was captured on 18 December 1940, and this was not his first voyage of the war – he had joined the Richard de Larrinaga on 29 November 1939 (this was itself later lost in May 1941). This should have qualified him for some medals – the War Medal (1939-1945) only requires a minimum 28 days at sea – so my guess is that he simply did not claim those he was entitled to.

The Duquesa is an example of how complicated matters could be. At the time Jeremiah was captured, it was in the South Atlantic (actually just south of the Equator, south west of Freetown, Sierra Leone) but it was not lost at this time; that occurred in 1941 while in use by the Germans.

At the time of capture, Jeremiah was part of a group of around 600 prisoners drawn from the crews of several ships attacked by raiders including the German heavy cruiser Admiral Sheer. The Duquesa was better kept afloat since it was refrigerated and filled with meat and eggs from South America. It was also used in an attempt to lure Royal Navy ships into a trap as they tried to rescue it, designed to allow other German ships to move more freely in the North Atlantic.

The prisoners were sent off to Europe while the ship remained in the Atlantic serving to resupply various German ships so they could remain at sea without risking returning to German-held ports. Crews captured by the German raiders could be moved from one ship to another, often also captured ships, before they reached Europe – all the while at risk of the worst the war and the oceans could throw at them. One of Jeremiah’s prisoner of war cards suggests he was in Bordeaux by 7 April 1941.

The remainder of the information found in BT 350, BT 364 and BT 382 waits to reveal Jeremiah’s peace-time service by detailing the names or Official Numbers of ships he served on from the Laconia from December 1918 to the Ramon de Larrinaga from January 1939, and on after the Second World War to his final engagement on the Maria de Larrinaga ending in July 1955.

The last entry in his service record (BT 382/28) is of him being discharged at his own request in October 1955 following a period in Sefton General Hospital. He died in 1957.

The various records we hold for merchant seamen are described in our guide to Merchant seamen serving since 1918.

Supplementary details were obtained from other records as indicated and marriage records made available online by Liverpool City Council via Ancestry. Ship history information was obtained from various sources online.

Thanks Ian. It’s good to hear the personal stories behind the photos.

What an interesting and also sad story. The fact that he was still having to go to sea at the age of 65 and then only living for another 2 years. His must have been a hard life. As a matter of interest: was his family contacted about the records that you found? Thanks. Ruth

What a hero and hard working man. So sad he was not awarded war medals automatically at the end of the conflict. His patriotic and dedication towards serving our British Isles during difficult times should be applauded !

Unfortunately, medals were not automatically issued, but had to be claimed by the merchant seaman.

A man of courage in my opinion. I hope hiis family are given his Second War Medals.

My own father was also a Merchant Seaman, serving aboard TSS Natia sunk October 7/8th 1940 sent to Marlag Nord and repatriated in July 1944 also because of cardiovascular problems. He lived until October 1960.

Really interesting. But so sad that we don’t seem to have learned by our mistakes, these seagulls things continue to happen.

Kathleen.

A tragic and immediately engrossing account. Thanks very much for publishing it.

Very interesting story. Times were tough back then to be sure.

I come from Liverpool therefore can speculate that he lived in Liverpool because not only was it an important Port but because there has been a ‘black’ population there for a couple of centuries. These, like the Chinese were seamen and accepted by the local population, his wife has an Irish name. The centre of the ,’black’ population was Upper Parliament Street

I must admit the subject of Merchant seaman being taken prisoner of war had not really entered my consciousness.We are all aware of men from the forces being taken prisoner.This is such a sad story,do we have any idea how many people from the Caribbean served in the Merchant Navy. It is difficult to imagine what Jeremiah thought about his life,and then to be bombed out in WW2.

Merchant seamen came from all over the world across both wars, and also before and after of course. It is only as records collections such as this are catalogued to include information such as place of birth that determining things like this will become a little easier for future researchers. As it is now, I don’t think there are simple existing statistics available to say what contribution was made by those from the Caribbean, or elsewhere.

Very interesting study and a great overview of the difficulties working as a seaman in the wars. As previously mentioned, to go through that turmoil and only have 2 years of retirement. Thank you for this study.

It is good to read that your Merchant Navy war records are being made more easily available. This will help the process of making the vital roles the MN played in both World Wars more generally known and appreciated. I, a ‘latter-day’ merchant seaman, have the deepest admiration for all those who served in those times.

My great uncle, James Young (b 1887), was a Marconi man, when his ship the Georgic carrying 1200 horses was sunk off the cost of Newfoundland in 1916 by the SMS Möwe a merchant raider. He and his crew members were interned at Wahmbeck, a small resort, near Hanover until the end of the war. I have photographs of the men taken during their internment which may be of interest but am not sure how best to share them.