The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was created by statute in 1833. Sitting in Downing Street in London, it was staffed by senior British judges, who were later joined by senior judges from a number of the British colonies. In addition to hearing appeals from the ecclesiastical courts, from the High Court of Admiralty and Vice-Admiralty Courts, and from the Isle of Man and Channel Islands, it was the highest court of appeal for the British Empire. It remains the final court of appeal for a number of Commonwealth countries today.

The printed appeal papers of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, along with printed papers relating to some earlier appeals, were transferred by the Ministry of Justice to The National Archives in 2019 and are found in PCAP 6. While partial sets of these printed appeals can be accessed at the British Library, Gray’s Inn and the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies in London, the set of appeal papers transferred to The National Archives were the Privy Council Office’s own copies and comprises the most complete set available. The series will continue to accrue as more records are created and accessioned. They are subject to a 100-year closure period.

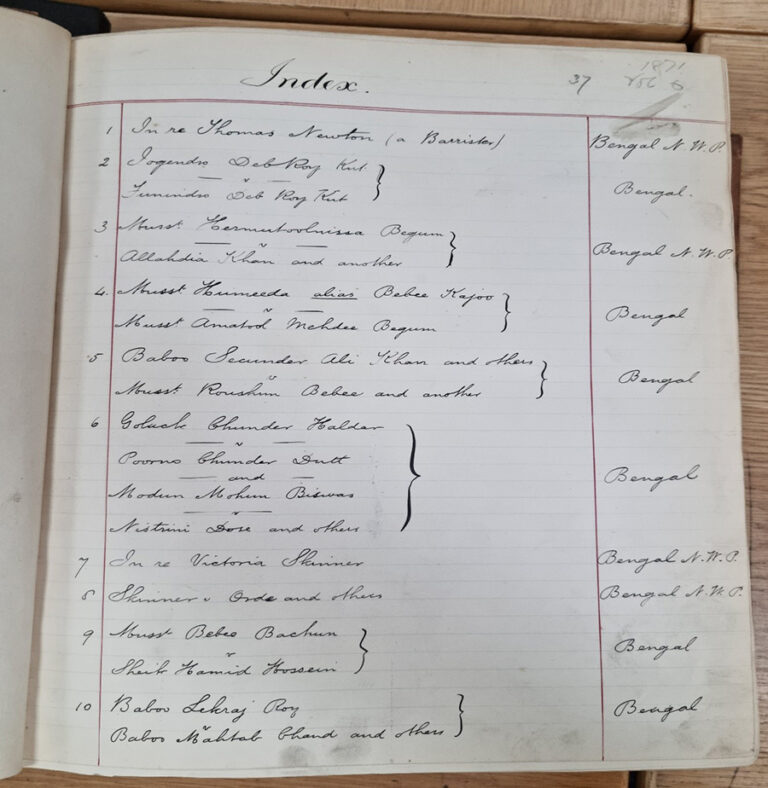

Covering, at present, a period from 1792 to 2008, PCAP 6 extends to nearly 3,000 bound volumes, searchable on the catalogue, Discovery, in a range of ways, including by the names of the parties, date, originating court, and colony. They are truly global in extent and cover a broad range of legal topics, from company law and native title to succession and divorce.

To understand the significance of the Privy Council Appeal Papers I would like to begin by telling a story. It is a story which is told through the papers for the appeal in the case of Skinner v Orde found in PCAP 6/84/7, which came from Bengal in British-ruled India to be decided by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1871. It is the story of Victoria Skinner, also known as Nawshaba Begum, and her family.

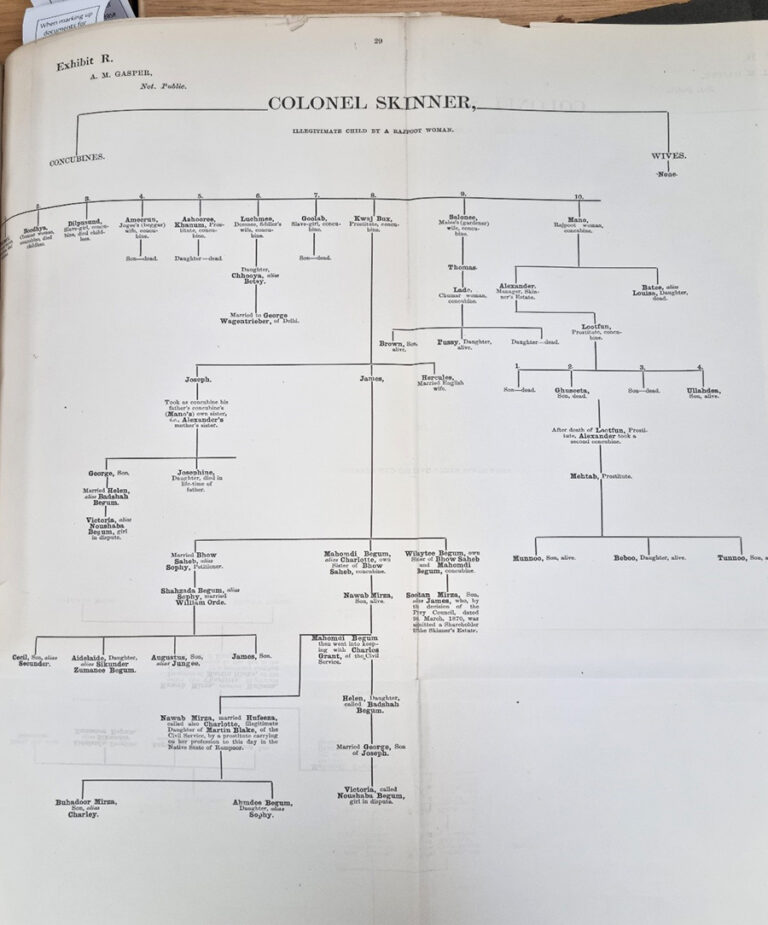

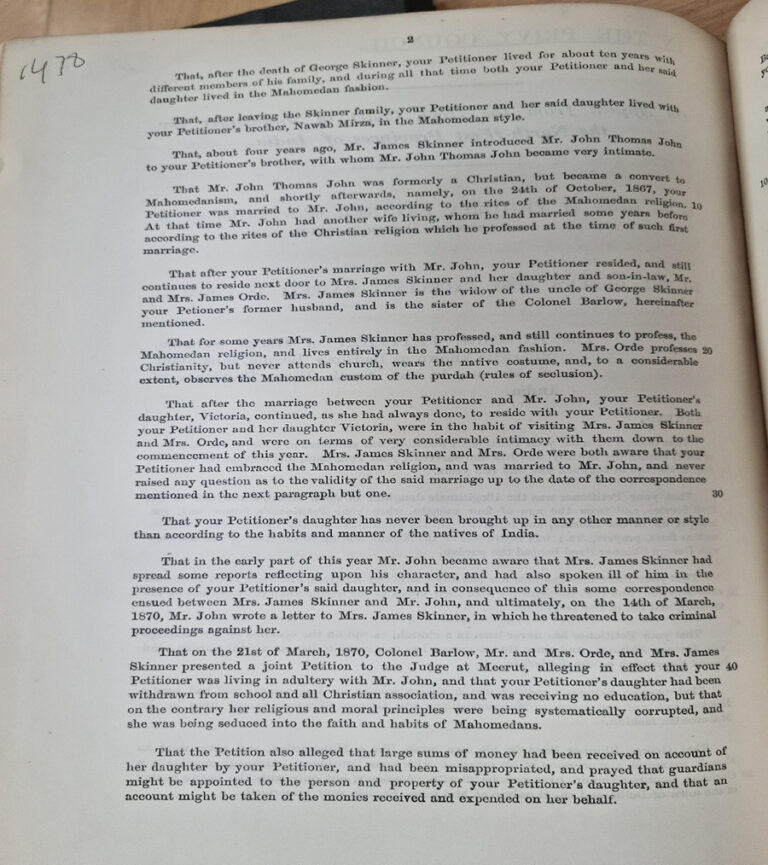

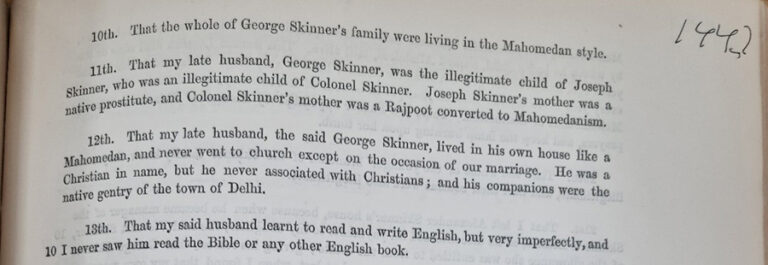

Victoria/Nawshaba, then aged 14, was the great-granddaughter of Colonel James Skinner, also known as Sikandar Sahib, the son of a Scottish soldier father and an Indian mother. Upon his death James Skinner/Sikandar Sahib left behind him both a substantial personal fortune and a large and complex family, consisting of many wives, concubines and children of different religions and cultures, to fight over it. Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s own father, who had also been an Anglo-Indian soldier, had died when she was a baby, in the Indian rebellion of 1857. Since then she had lived with her widowed mother. All was well until around 1869, when Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s mother, known as Helen Skinner or Badshaw Begum, re-married to a Muslim man. The marriage was polygamous, which was permitted under the Indian personal laws relating to Muslims. Victoria and her mother entered the household of the new husband, whereupon Victoria, who now called herself Nawshaba Begum, put aside her European clothes and habits, assumed native Indian dress, and ceased to attend school.

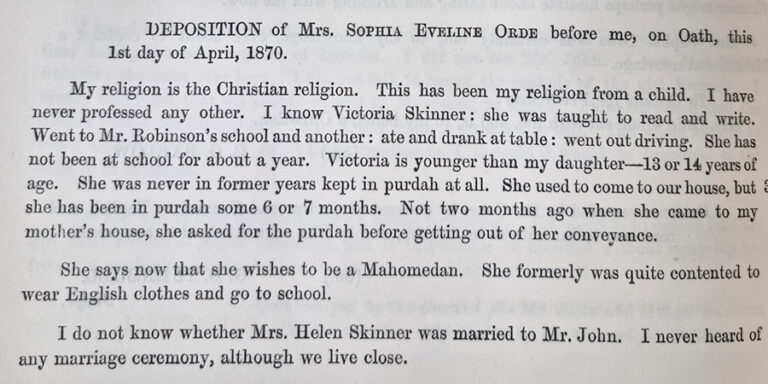

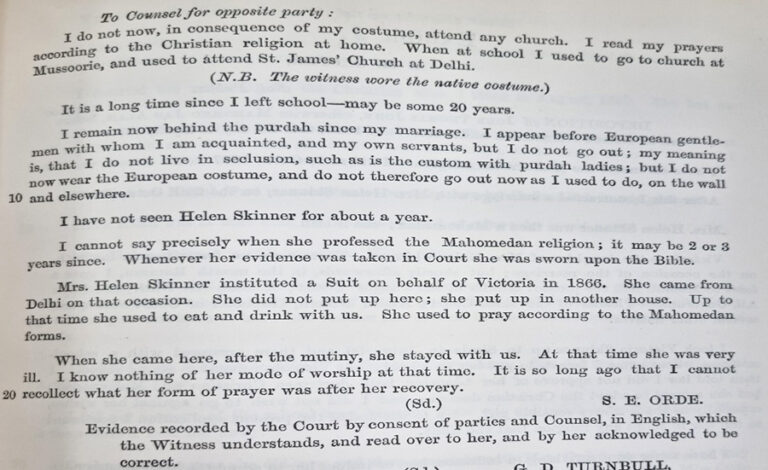

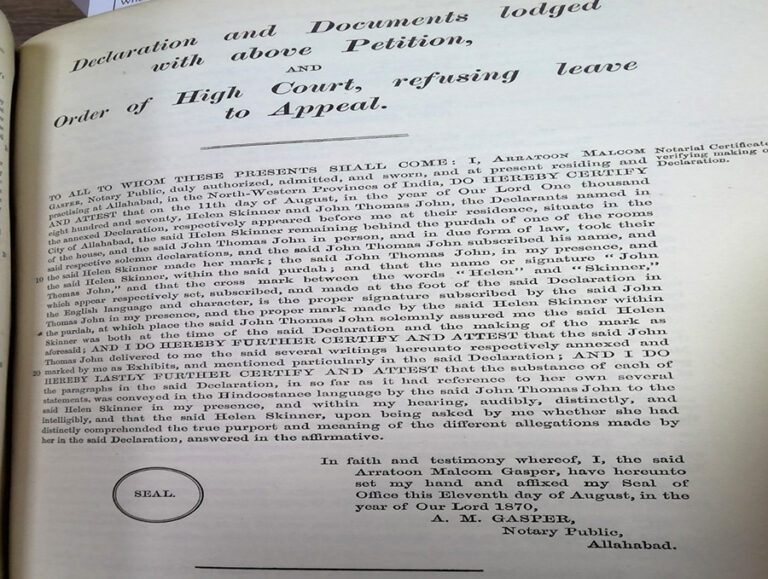

Concerned, members of Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s paternal family sought to remove her from her mother’s custody and to recover control of the income to which she was entitled under her great-grandfather’s will. They alleged that, like them, her father had been a Christian, and that she had been raised and educated as a Christian. They further maintained that her mother had only converted to Islam in order to take advantage of the personal laws which applied to Muslims in India and permitted polygamous marriage. Disputing this, and seeking to retain custody of Victoria/Nawshaba, Helen Skinner/Badshaw Begum protested that Islam had always been the faith of her family, and that she had done nothing wrong in asserting her legal right as a Muslim to enter into a polygamous marriage. For her part Victoria/Nawshaba, who strongly asserted her desire to stay with her mother, claimed that she too was a Muslim. Despite this, the lower courts, sitting in India, determined that she should be removed from her mother’s care and placed, first, under the care of a female relative, and then in a boarding school. Her mother appealed, taking her case before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.

Helen Skinner/Badshaw Begum was given leave to appeal to the Judicial Committee on the grounds that the case had important implications for relationships between different faith communities in India, and also for questions of religious education. Despite its wider significance, the question to be decided was an apparently simple one, namely, who should have custody of Victoria/Nawshaba?

While the question was simple, determining the law by which an answer should be arrived at was, to say the least, complex. Firstly, it had to be determined which of the bodies of faith-based personal laws operating in India applied to the parties in the case. Secondly, the judges had to grapple with differences between Indian and English law, which were at odds on the question of child custody. While the English law of the time generally gave the father custody of children, and control over their religious education, Indian law was more progressive. Laws passed specifically for India prescribed that the custody of children should be decided in the best interests of the child herself. But what were the best interests of the child in this instance? A significant part of answering both of these questions lay in determining the religion of Victoria/Nawshaba, her mother and father, and the wider family. Again, this was anything but straightforward, and indeed made the complexity of the legal issues pale into relative insignificance.

Even if the Islamic faith of Victoria/Nawshaba and her mother remained unchallenged, determining the faith of her father and paternal family posed a considerable conundrum. The patriarch who had founded the whole dynasty, Colonel James/Sikandar Skinner, was renowned for having built the St James Church in Delhi, but he was also credited with having built a temple and a mosque. The religion of his son, Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s father, was the subject of contested accounts and conflicting evidence and proved impossible to determine conclusively. Meanwhile, cross-examination in the lower courts of the self-described Christian paternal relatives had revealed that they in fact embraced multiple cultural and religious features and identities. For example, Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s grand-aunt asserted that she respected both the Quran (the holy book of Islam) and the Bible. What, then, were the judges sitting in London to decide?

In the end, neither Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s self-identification as a Muslim, nor the existence of distinctive and progressive Indian laws, were enough to ensure that the girl’s wish to remain with her mother was respected. Baffled by the family’s religious and cultural complexity, but following English legal and cultural norms, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that a child shared the religion of her father. They found that Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s paternal family, including her father, were at least nominally Christian. It was therefore in Victoria’s/Nawshaba’s best interests that she should be removed from her Muslim mother’s custody and raised as a Christian. Accordingly, she was taken from her mother’s care and sent to a boarding school for British expatriate and mixed-race children.

The story told in Skinner v Orde is, self-evidently, a long and complicated one. It reflects many of the common themes of colonial and imperial history. It is a story, like many others, which we would have few means of uncovering without the extensive records held within the Privy Council Appeal Papers in PCAP 6. These bring together in one place all of the proceedings and written records of evidence in a suit, from its first hearing up to the order in council which put into effect the report or judgment of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Rarely is such a rich and accessible feast offered to those using legal records, who are typically far more accustomed to piecing together the fragmentary remains of multiple document series as they seek to reconstruct proceedings in individual cases.

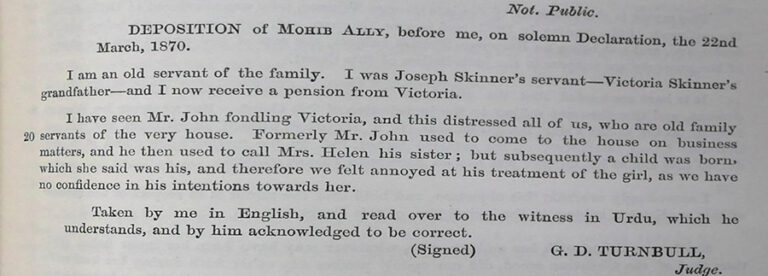

No less important are the possibilities which the Privy Council Appeal Papers offer to those with an interest in the social, religious and economic histories of the British Empire. Within their pages we find not only business accounts and details of land holding, but also detailed genealogical information, together with numerous evidences of attitudes towards religion, class, ethnicity and status. The voices of those providing such evidences include those of the marginalised or overlooked, which history so often struggles to capture, including, as we have seen, the voices of women, children, the non-white subjects of empire, and domestic servants.

Perhaps nothing more needs to be said to establish the significance of the Privy Council Appeal Papers in PCAP 6, but I would conclude by drawing your attention to their value, not only as an abundant source of insights into the complex lives and identities of those who those who lived within, and administered, the British Empire, but also as a means of better understanding the complex role played by law and lawyers in shaping those lives and that administration. Law was at the heart of the British Empire. Government by law, rather than by force, was seen to be a key attribute of the ‘civilised’ society which Britain saw itself as bringing to its colonial possessions. So, too, law, or at least the appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, was a powerful unifying power in the otherwise rather disparate and heterogeneous empire. All British subjects, no matter where they were, had a constitutional right to approach the Crown, in the form of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, to seek justice. Law, then, was not merely a tool of British imperial rule, but also a resource for the people of the British Empire, many of whom, like Helen Skinner/Badshaw Begum and her daughter, believed that justice could be found there.

Again, this in itself makes a striking case for the significance of the Privy Council Appeal Papers, but we would do well, finally, to dwell on both the nature of the British Empire and the approaches taken to its legal governance. Britain never adopted a single unified approach to the administration of its empire, nor did it transplant its common law and institutions wholesale in its possessions across the globe. Rather, the means by which its colonial possessions were governed, and the laws to which their peoples were subject, depended upon a range of factors, including not only their demography, and their unique political and social circumstances, but also by the varied means by which they had come under British imperial rule. Given the extent of the British Empire, its ethnic diversity, the longevity of its evolution, and the piecemeal nature of its development, what resulted was a complex mosaic of imperial law and governance, incorporating a broad array of sources and ideas, and varying from place to place.It was the daunting task of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, sitting at the crossroads of empire, to bring justice (or at least legal sense) out of this often fragmented and seemingly unconnected mosaic. The richness of the records which its travails created is hard to overstate, yet they remain sadly neglected. It is my hope that this blog, together with the work being done at The National Archives to enhance the catalogue, and to improve our understanding of them and their relationship to other document series, might begin to change that.