October 2020 marks the start of the 550th anniversary of what historians know as the ‘Readeption’ of 1470-71, a dramatic six-month period of the Wars of the Roses in which not one, but two, kings would both gain and lose the English crown, sometimes in violent fashion.

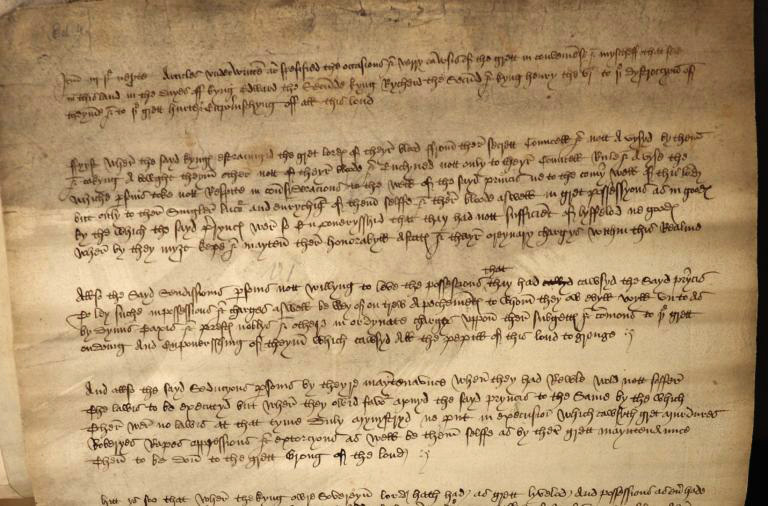

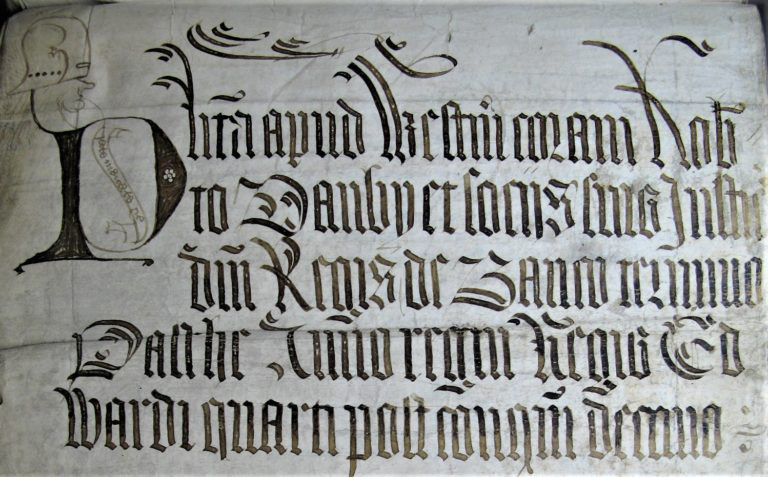

What was the ‘Readeption’? The term itself, meaning reclaiming [of royal power], is taken from original records from the time, and refers to the period between October 1470 and April/May 1471[ref]While the Readeption itself formally ended in April 1471, with Edward IV’s return to London, its aftermath would continue into May, so both months have been included here.[/ref] in which Henry VI (1422-61, 1470-71) temporarily regained the English throne, which he had lost to his rival, Edward IV, almost a decade earlier.

Driven by factionalism, family disputes, and uneasy alliances, the Readeption was a turning point in the Wars of the Roses, which questioned the loyalties of those at all levels of society.

Over the next six months, the medieval team here at The National Archives are going to be digging deeper into some of the personal stories of those who found themselves at the centre of events, to re-assess this important, but often overlooked, period of English history. Here we set the scene, with a brief overview of some of the key events.

Why did it happen?

Henry VI had succeeded his father, Henry V, as an infant in 1422. While the early years of his reign (under regency government) saw a high point of English control in France, with Henry crowned king of France in 1431 (just after his 10th birthday), as he reached adulthood it soon became clear that he shared little of his father’s personality. Pious, shy, and almost entirely uninterested in war, Henry preferred religious foundations – including Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge – to his father’s French exploits, and English control in France declined rapidly.

Throughout the late 1440s and 50s, his reign became increasingly unpopular, reaching a climax with the final expulsion of an English presence and lordship in France (outside Calais) in 1453. Popular uprisings, such as Cade’s rebellion (1450) sought to assign blame for the failings in France, while events were also exacerbated by Henry’s own mental health. As his reign progressed, Henry became increasingly prone to periods of mental instability, leaving him unable to rule, and the governance of England left in the hands of protectorates.

By the 1450s, a large faction of the nobility, led by Richard, Duke of York, had turned against Henry. In 1461, York’s son Edward, following his father’s death, had deposed Henry and seized the throne himself as Edward IV, after which he had roundly defeated the Lancastrian forces at the Battle of Towton, one of the bloodiest battles in English history. Henry VI, after a few years of travelling around the north of England reliant on Lancastrian sympathisers, had been locked in the Tower of London, and the Yorkists were firmly on the throne.

Warwick the Kingmaker

Edward’s own position, however, was far from secure. He was a young, popular and active martial figure – very much the opposite to Henry – but he was still partially reliant on the support of his nobility, particularly Richard, Earl of Warwick, known as ‘the Kingmaker’, who had worked with his father, the Duke of York, to secure the Yorkist claim, and now served as the power behind the throne.

By the middle of the 1460s, their relationship had soured considerably. Disputes over foreign policy caused friction, while marriage politics provided yet more tension. In 1464, Edward married the widow of a Lancastrian knight, Elizabeth Woodville, a woman considered by Warwick to be of insufficient social status for the king to remove him from the lucrative European marriage market. Elizabeth also had a large family who needed patronage, with positions, lands or titles, often at the expense of Warwick’s family.

At the same time, Warwick was becoming increasingly close with Edward’s younger brother, George, Duke of Clarence, who had joined Warwick’s household under his tutelage. George was at this time one of the most eligible bachelors in Europe, and a marriage was proposed between him and Warwick’s daughter, Isabel Neville, which would have seen him inherit a share of the Kingmaker’s vast estates through his wife (provided Warwick died without a male heir). Edward, however, refused to agree to the marriage.

By 1468-69, the two sides were at breaking point, and on 11 July 1469 Clarence and Isabel were married in Warwick’s presence at Calais. The very next day, the two men issued a manifesto, claiming that they wished to rid the king of his ‘evil counsellors’, and referring back to previous kings who had been deposed due to the evil counsel they had received.

They stated that they would be at Canterbury on 16 July, and asked their supporters to join them there, arrayed for war. Their coup was initially successful, in part due to Edward’s slowness in responding, and infighting among his supporters, and Edward was briefly taken captive, with several ‘evil counsellors’ executed. Efforts to rule effectively in his absence, however, proved futile, and Edward was eventually released, after which he made an effort to reconcile himself with Warwick and Clarence, and to bring them back into his circle to ensure their future support.

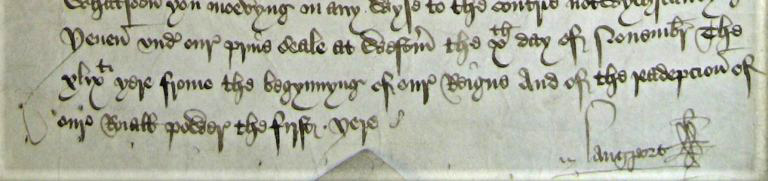

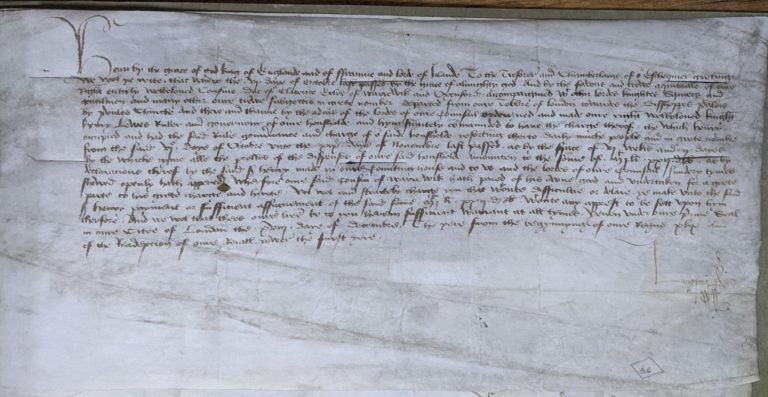

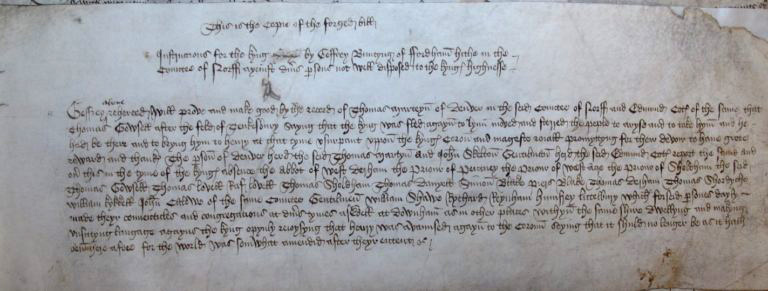

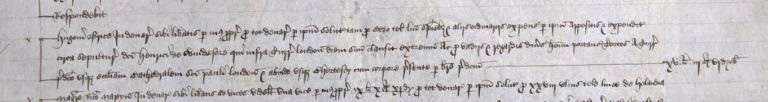

‘Yet the said duke and earl unnaturally intending his destruction and the subversion of the realm and to make the said duke (i.e. Clarence) king of the realm against God’s law and all reason and conscience … provoked and stirred up by their writing Sir Robert Welles late captain of the commons of Lincolnshire to levy war against him, as they did with banners displayed and in plain battle until his highness by God’s help put them to flight.’

Proclamation made 31 March 1470 against Warwick and Clarence [Catalogue ref: C 54/322 m. 8d]

Less than a year later, however, the two would rebel once again. Having (allegedly) spread rumours around England of Edward’s illegitimacy – probably intended to give Clarence a clear route to the throne in place of Edward in the event of a deposition – Warwick and Clarence provoked a series of uprisings in order to tip the country back into crisis. This time, however, they would not be successful, with their supporters routed at the battle of ‘Losecoat field’ in Lincolnshire, where evidence was later found implicating the two men. Warwick, Clarence and their retinues fled to France, where they soon sought a new alliance with the French king and the exiled Lancastrian forces of Henry’s wife, Queen Margaret of Anjou, and heir, Prince Edward.

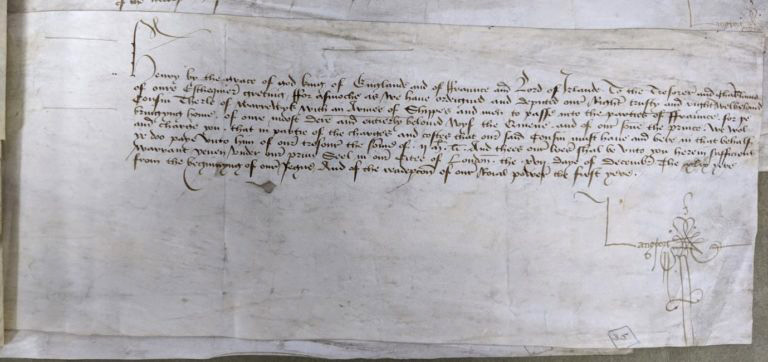

In this remarkable agreement (Warwick would have been one of the most hated Yorkist usurpers in Queen Margaret’s eyes), Warwick and Clarence agreed to return Henry VI to the throne in place of Edward, in return for money and support. Warwick’s daughter, Anne Neville, was betrothed to Prince Edward, thereby securing his status and power at court, while Clarence may have been accepted as heir to the throne should Henry’s line fail. On 13 September 1470, the exiled forces landed in Devon and declared their intentions to restore Henry to his throne.

Henry VI’s Readeption

At the time of Warwick and Clarence’s arrival in south-west England, Edward was himself in the north, attempting to put down yet another uprising. Edward had seemingly assumed that the exiles would again struggle to gain supporters, but clearly miscalculated, both in his decision to leave the south coast relatively undefended, and in his mismanagement of the nobility and their lands, particularly in the north of England. Warwick’s brother, for example – John Neville, Marquis Montagu – had initially remained loyal to Edward, but was undermined by Edward’s efforts to reconcile former Lancastrians, and declared for the exiles shortly after their return[ref]He had been stripped of his title of Earl of Northumberland in March 1470 in order to reconcile a former Lancastrian, Henry Percy, and had been granted a new position of Marquis of Montagu in the south of England instead. Edward may have considered this adequate compensation, but Neville as a northern lord clearly felt slighted by the perceived insult.[/ref].

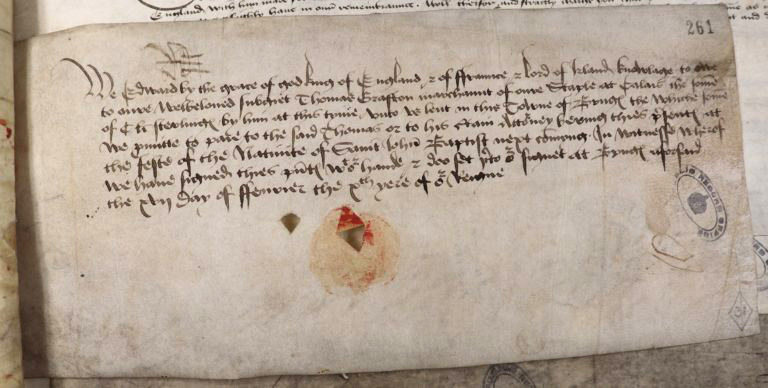

Seeing the writing on the wall, Edward and a small retinue turned and fled east, almost drowning in a perilous crossing of the Wash, before reaching Bishop’s Lynn at the end of September and setting out for Burgundy on 2 October penniless[ref]Edward was apparently reduced to paying the master of the ship with a furred gown in lieu of money: Ross, Edward IV, p. 153.[/ref]. The path to Henry’s Readeption was clear and on 6 October he was freed from the Tower of London and formally restored to power.

Edward’s flight from England without resorting to pitched battle allowed his supporters among the nobility to reconcile themselves with the new regime, and accordingly they were able to avoid significant punishment or mass forfeitures of land, although the new regime was quick to grant key positions within the great departments of state to prominent Lancastrians. Warwick positioned himself as Lieutenant of England, once again placing himself as the power behind the throne.

Elsewhere in society, institutions and individuals sought to confirm grants made to them during Edward’s reign, to secure pardons for themselves, and to ingratiate themselves with the new regime. All eyes would have been on the Readeption parliament assembled on 26 November 1470, at which several institutions sought to represent their own interests with the new regime. One blatant example can be seen from the chapter of St George’s College, Windsor, who paid one of their number, Baldwin Hyde, his full daily wages as if he was present in chapel throughout the duration of the parliament. He was actually acting as Clerk of the Parliament, and was keeping an eye out for legislation that might go against the chapter’s interests[ref]Unfortunately we have few details of this parliament, given that the official record of proceedings – the Parliament Roll – was in all likelihood destroyed upon Edward’s return in 1471: Hannes Kleineke and Euan C Roger, ‘Baldwin Hyde, Clerk of the Parliaments in the Readeption Parliament of 1470–1’, Parliamentary History, 33 (2014), pp. 501-10.[/ref].

In December 1470, problems re-emerged among the Yorkist faction in the Readeption government. Warwick was sent to France on 17 December to bring Queen Margaret and Prince Edward back to England, leaving Clarence in London to deal with the increasing numbers of Lancastrians returning from exile and seeking restoration of their former lands, many of which were now in new hands, including Clarence’s own. At some point, Clarence realised he had made a mistake, and that there was no way his position at court could be better than it had been under Edward, particularly with the return of Queen Margaret and Prince Edward imminent. While still displaying signs of loyalty to the Readeption regime, he now planned to switch sides once again and opened up secret correspondence with his big brother in exile.

Edward IV returns

In exile in Burgundy, Edward IV had been busy securing support with his brother-in-law Charles the Bold, who provided him with ships and £20,000 (equivalent to almost £14 million today) for his cause, and by 11 March 1471 he had set sail back to England with a small retinue of loyal supporters. Initially attempting to land in East Anglia, but faced with opposition, Edward landed at Ravenspur in Holderness[ref]This was the same location from which a previous king, Henry IV, had landed to seize the throne from Richard II, and was probably a deliberate move by Edward.[/ref]. Initially claiming that he only wished to recover his dukedom, Edward travelled to York, where he was eventually able to convince the citizens to let him in. Slowly, but surely, troops joined Edward as he moved south, and on 2 April he was reconciled with Clarence, and his army, giving him the numbers he needed to march on London. The Lancastrian forces at this time were spread thin, and Edward entered London with little problem (aided by the fact that his leading supporters who had been imprisoned in the Tower by Warwick had managed to escape and take the Tower for themselves). Edward ordered that Henry VI and some of his associates be returned to the Tower, ending the Readeption.

The wider conflict, however, was not finished. Warwick and Queen Margaret were both still at liberty, with their forces. A few days after Edward had entered London, Warwick left the safety of Coventry, where he had assembled his forces, and marched south, meeting Edward and his troops near Barnet. The battle, fought in fog and poor visibility, with Edward IV at the heart of the action, would be won through a combination of distrust and confusion among the Kingmaker’s army, when the division led by his brother inadvertently attacked the forces of the Earl of Oxford. Fearing they had been double-crossed, Oxford’s troops fled the field leading to a rout of Warwick’s army, in which the Kingmaker himself was killed by some of Edward’s men.

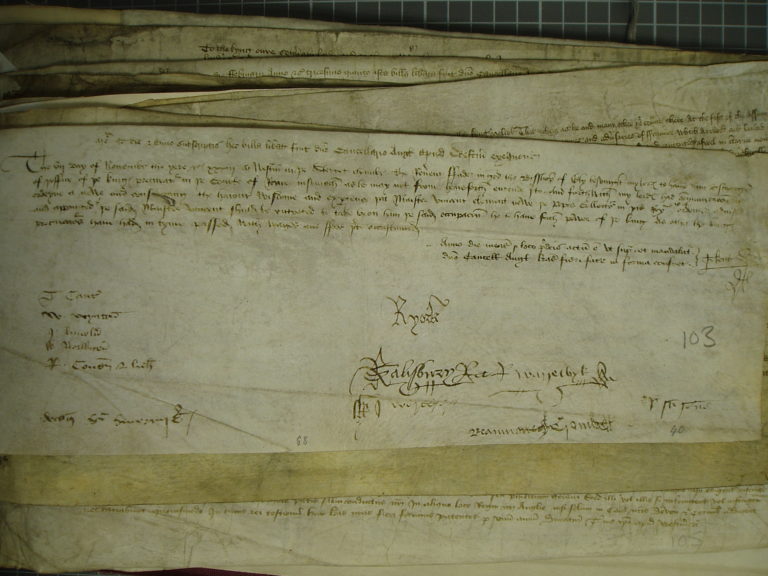

‘our title afore this time in divers manners hath been openly declared … as also by victory given to us by the Almighty, in battles against our adversary Harry and his adherents, and in especial now … in the field beside Barnet, where battle was moved against us by Henry late duke of Exeter, John marquis Montague, Richard earl of Warwick, John earl of Oxford and many others in great multitude, rebels, adherents to the said Harry our adversary … in which conflict marquis Montague and Richard earl of Warwick with many others were slain’

‘Margaret calling her queen, which is a French woman born, and daughter, to our extreme adversary of all our land, and her son Edward, assembled a great number of Frenchmen, besides other traitors and rebels, now have entered our realm, robbing and spoiling, and have levied war against us … we declare the said Margaret, Edward her son [and others] to be our open and notorious traitors, rebels and enemies’

Proclamation made by Edward IV after the battle of Barnet [Catalogue ref: C 54/323 m. 26d]

Celebrations would not last long; news would soon reach Edward of Queen Margaret and Prince Edward’s arrival in England. The Lancastrian army, marching towards Wales from Weymouth, were intercepted by the Yorkist forces at Tewkesbury and soundly defeated, with Prince Edward one of those killed in battle. The Lancastrian troops fled to Tewkesbury Abbey (which did not have the status of a sanctuary), and were brutally executed by the pursuing Yorkist army[ref]Edward himself may have been at the centre of the bloodshed according to one chronicle, his hand eventually stayed only by the intervention of a priest carrying the sacrament.[/ref]. Other principal Lancastrians were also executed in the aftermath, while Queen Margaret was taken into custody.

The threat to the throne was now almost entirely extinguished (with the exception of one last pocket of resistance led by the Bastard of Fauconberg[ref]Thomas Neville, an illegitimate son of another of Warwick’s brothers, William Neville, known as the Bastard of Fauconberg, was part of the Readeption forces, and had been patrolling the channel against a Yorkist invasion. In May 1471, he besieged London on two occasions while Edward and his forces were at Tewkesbury, but the city was (just about) able to resist their attacks. By the time the royal forces returned to London, the threat had largely abated and Fauconberg submitted to royal favour a few days later: Kleineke, Edward IV, pp.120-2.[/ref]), but Edward had learned from his previous mistakes, and was clearly determined to snuff out the Lancastrian threat once and for all.

‘King Edward has not chosen to have the custody of King Henry any longer, although he was in some sense innocent, and there was no great fear about his proceedings, the prince his son and the Earl of Warwick being dead as well as all those who were for him and had any vigour, as he has caused King Henry to be secretly assassinated in the Tower, where he was a prisoner … He has, in short, chosen to crush the seed’

Milanese Ambassador at the French Court to the Duke of Milan[ref]Sforza di Bettini, Milanese Ambassador at the French Court to the Duke of Milan: Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts in the Archives and Collections of Milan 1385-1618, ed. Allen B Hinds (London, 1912), number 220.[/ref]

Edward returned to London on 21 May, committing Queen Margaret to the Tower, and that night Henry VI died, almost certainly murdered, on Edward’s orders[ref]The official account of Henry’s death claimed that he died of ‘pure displeasure and melancholy’, but even at the time it was widely suspected that he had been murdered.[/ref]. Henry’s body was displayed in public before being transported from St Paul’s Cathedral to Chertsey Abbey in Surrey for burial, where it would achieve cult status.

The Readeption was over, and Edward’s second reign had begun, a reign considerably more secure than his first. Warwick’s influence was no longer present at court, the Lancastrian enemy had been decapitated, and Edward’s son and heir had been born in sanctuary during his exile in Burgundy, securing the Yorkist dynasty and Edward’s legacy for another decade.

Over the course of the 550th anniversary of 1470-71, we will be digging deeper into some of the stories, characters and events of the Readeption, and how they were recorded in the official records of the day. Keep an eye on our social media channels and our blog to find out more.

#TeamNeither, as for the vast majority of the population nothing changed and most of whom did not care. ..

But re. Edward’s landing at Ravenspur, didn’t he originally intend to land on Norfolk but was deterred by local pro-Henrician defenders?

Ignore my remark re. Ravenspur, I missed that you’d already addressed the point in the text!

Very succinct description! The only thing I would add would be that some of the “evil advisors” that were executed when King Edward IV was first taken prisoner by Warwick happened to be his queen’s father and brother! I think that adds a whole other layer to the politics of the time. I know if my husband wanted to forgive someone that killed my family, I would have some issues with it!

This is great stuff!

I am working on a book on the Readeption, to be published about 2023. I am glad to see the documents you have quoted, which the catalogue has not turned up.

I will be following this enthusiastically