This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

Reflecting on her time in the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols, Superintendent Sofia Stanley declared ‘I have given the very best service of which I am capable to the Metropolitan Police’ (see footnote 1).

This blog post focuses on three women who joined the Metropolitan Police: Sofia Stanley, Elinor Robertson and Lilian Wyles. Drawing on the records of the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office, it explores their experiences in the police and the work they undertook during the 1920s.

The Metropolitan Police Women Patrols were established in 1919 – this was the first time women could formally join the Metropolitan Police. Find out more about the formation of the Women Patrols and their development during the 1920s in part one of this blog.

Sofia Stanley and Elinor Robertson

In 1918, Sofia Stanley was appointed Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols. During the First World War, Stanley supervised the London Women Patrols, an unofficial body of women employed by the National Union of Women Workers. Along with Stanley, Elinor Robertson was appointed as Assistant Superintendent.

In the photograph below of the first Women Patrols, Stanley (left) and Robertson (right) are pictured at the front of the group. Interestingly, the Women Patrols uniforms were made by Harrods (footnote 2).

Stanley and Robertson are distinguishable from the rest of the Women Patrols by the uniform they wore. A memorandum on the uniform stated that both the Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent wore a dark blue tunic, similar to the tunics worn by other ranks, ‘except that it has a roll collar and open lapels, is fastened with 3 black “M.P.” large size buttons, has black buttons on pockets and 2 on each sleeve.’ (footnote 3) They also wore a white shirt with a black tie, as the photograph shows.

Both Stanley and Robertson were responsible for the selection of new recruits (footnote 4). When conducting recruitment interviews, Stanley was open about the challenges of working as a Women Patrol, such as the criticism they often received from male police officers and members of the public. She was also praised for her management style and held weekly meetings with the Women Patrols (footnote 5).

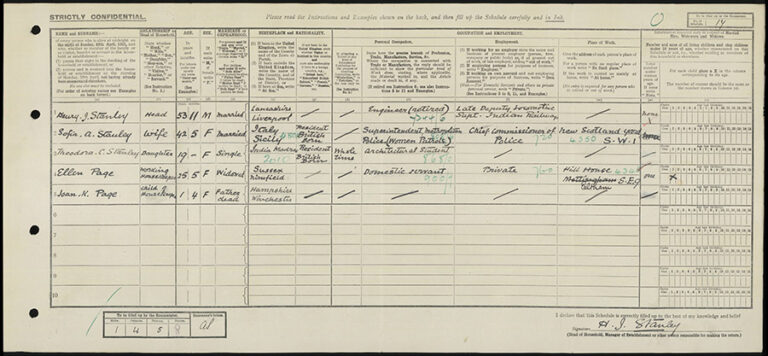

In the 1921 Census, Stanley is recorded as living in Lewisham, London, with her husband, 19-year-old daughter, and a housekeeper. The housekeeper’s one-year-old daughter also lived there. Stanley’s occupation is listed as ‘Superintendent, Metropolitan Police. (Women Patrols).’

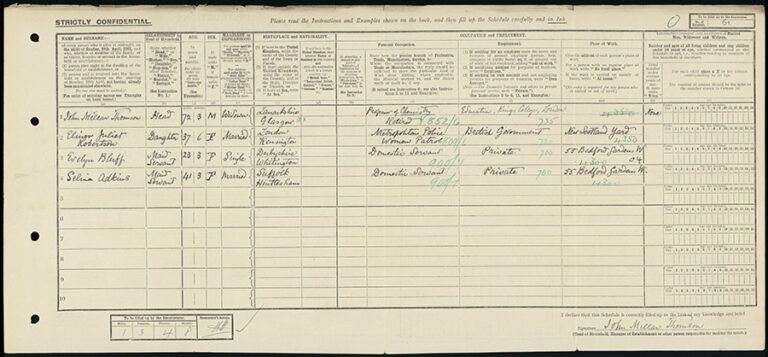

Very little is known about Robertson. She is listed in the 1921 Census as living in Kensington, London, and her occupation is described as ‘Metropolitan Police Woman Patrol’. While Robertson is noted as ‘married’, she is recorded as living with her father, John Millar Thomson, along with two domestic servants.

A letter written by Stanley on the topic of accommodation for the Women Patrols reveals that Robertson lived permanently apart from her husband. The letter read ‘Mrs Robertson lives with her old father and has her own furnished room which she pays £1 per week. She receives no support from her husband.’ (footnote 6) It is therefore likely that Robertson and her husband were separated.

This letter also provides a valuable insight into Stanley’s personal circumstances. Stanley writes that all the accommodation for the Women Patrols was filled, although there were still 21 single women who were not provided with accommodation, and 30 married women living in their own homes. She goes on to state:

I have therefore to ask the consideration of the Commissioner of the question of lodging allowance for the Women Patrols not provided with quarters, in order to treat all the women with equal fairness … In my own case, I have an invalid husband who has only a small pension and I bear all the cost of rent and rates. When I took my house a year ago I selected a district in which both rent and rates were low, but the latter have now been increased to 19/9 in the £. My rent is £66 per annum.

Letter from Sofia Stanley to the Metropolitan Police Office, 16 February 1921, MEPO 2/2671, The National Archives

Despite Stanley’s middle-class background, it appears that she was solely responsible for providing for her family, as her husband (Henry Stanley) was left paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair following an accident (footnote 7).

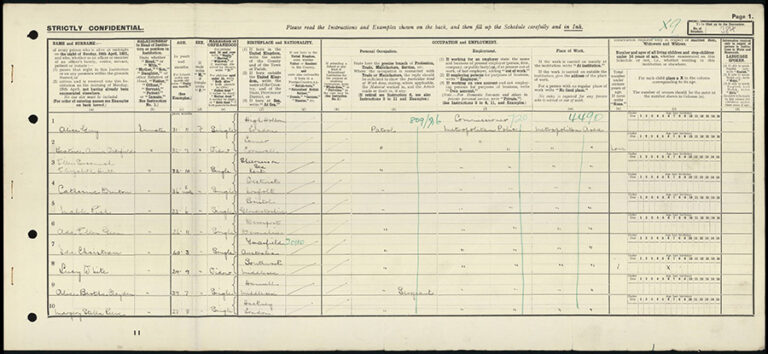

Many unmarried and widowed Women Patrols lived at Section House, Ixworth Place, London, which can be seen in the 1921 Census.

It is noteworthy that both Stanley and Robertson were married. From its establishment in 1919, married women were eligible to join the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols. Stanley observed in 1920 that ‘Marriage is no bar to the force; in fact there are some duties for which married women are more fitted than single. Our work is chiefly among women and children.’ (footnote 8) Indeed, it was believed that women’s supposedly caring and materialistic qualities made them well-suited to the role, given the work of the Women Patrols largely focused on welfare issues. However, a marriage bar was introduced in 1927 for new recruits, and subsequently to existing married women already employed in 1931 (footnote 9).

Lilian Wyles

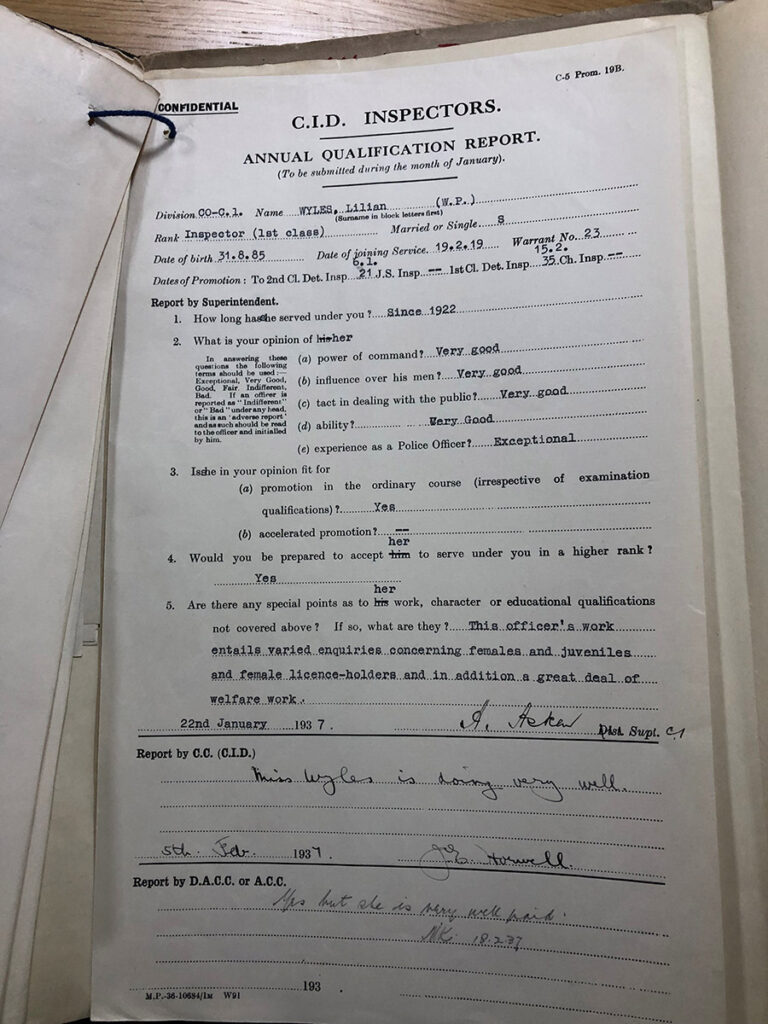

Another influential figure in the Women Patrols was Lilian Wyles. Similar to Stanley, she was also involved in the women patrols run by the National Council of Women Workers prior to joining the Metropolitan Police. Her Annual Qualification Reports from 1937 states that she joined on 19 February 1919 (footnote 10).

Only a few months after joining, Wyles was promoted to Sergeant. In this role, she supervised the work of the Women Patrols in central and the East End of London (footnote 11). This photograph below shows Wyles wearing the Women Patrols uniform.

In 1921, Wyles was promoted to Inspector and became attached to the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). However, she wrote in her autobiography that she was ‘not wanted in the CID’, demonstrating how women were often met with resistance from male police officers (footnote 12).

In this role, Wyles largely took statements from women and children relating to sexual assault cases. Throughout her career, Wyles continued to carry out this type of work. Her Annual Qualification Reports from 1937 states that she is performing very well and that her work ‘entails varied enquirers concerning female and juveniles and female licence-holders and in addition a great deal of welfare work.’ (footnote 13) The questions listed in the report use the pronoun ‘he’, which were crossed out and the pronoun ‘her’ written in, showing that male police offers were still the norm.

Before 1923, the Women Patrols did not have the power of arrest. Wyles was very vocal on this topic, and she recalled in 1921 that she often had to find a police constable if an arrest was needed:

This action of ‘rushing up and down to find a constable’ may be meritorious for the voluntary patrol, but when undertaken by a member of a Force having status, authority, and defined powers, it becomes undignified, if not ludicrous.

‘The Women Police Movement’, Common Cause, 28 October 1921, p. 493

Cuts to the Women Patrols and the dismissal of Sofia Stanley

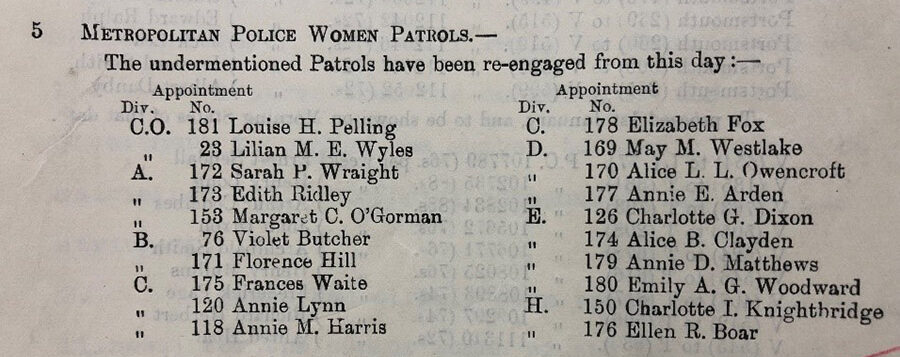

As part 1 of this blog discussed, the Women Patrols were reduced in 1922 to just 20, following a reduction in public spending. The Police Orders from 27 December 1922 lists the 20 Women Patrols who were retained (footnote 14).

As you can see from the list, while Wyles’ name is present, both Stanley and Robertson’s names are missing.

Prior to their reduction in 1922, the Women Patrols worked directly under superintendent Stanley as a separate body from the rest of the Metropolitan Police. However, it was subsequently decided that the Women Patrols would be posted to various divisions, and would report to the male superintendent of their division (footnote 15). As a result, the positions of Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent were no longer required.

Although Robertson was offered a new position by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, she refused the appointment and retired from the police on 13 May 1922 (footnote 16). Despite leaving the Metropolitan Police, Robertson continued to campaign for the retention of the Women Patrols (footnote 17). She subsequently worked as an unpaid Private Secretary to Margaret Wintringham (one of only two female MPs at the time) who championed the work of the Women Patrols in the House of Commons (footnote 18).

Following the news that the Women Patrols were to be disbanded, Stanley hoped that with ‘passive resistance’, the Women Patrols could be saved (footnote 19). However, the Home Secretary, Edward Shortt, remained adamant that cuts were needed, and offered three senior Women Patrols (Wyles, Inspector Grace Dixon and Sergeant Violet Butcher) statement-taking positions.

However, Wyles made a statement against Stanley in which she accused her of urging the three women to delay their acceptance, as she supposedly believed the positions to be a ruse by the Home Secretary.

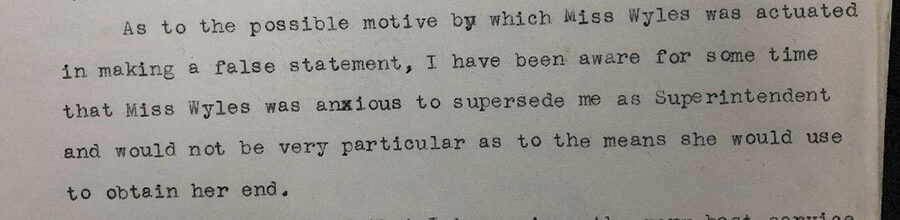

Stanley strongly denied the accusation from Wyles and stated that ‘I did say, I would be glad for these 3 women to continue in the Police Force’ (footnote 20). When pondering why Wyles would make a false statement, Stanley explained that:

It is difficult to know exactly what happened between Stanley and Wyles. Nonetheless, an enquiry into the matter was conducted and Stanley was dismissed. She subsequently moved to Calcutta to work for the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

At a time of rapid social and cultural change, as women began to enter careers traditionally seen as masculine, Stanley, Robertson, and Wyles were early policing pioneers. The records of the Metropolitan Police and Home Office provide us with a fascinating insight into the experiences of the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols during the 1920s.

Footnotes

- Statement from Sofia Stanley, 7 July 1922, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Edward Smith, ‘Stanley (née Croll Dalgairns), Sofia Annie (1873–1953), police officer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 9 April 2020, (accessed 10 May 2022).

- Memorandum on Metropolitan Police Women Patrols Uniform, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Letter to the Under Secretary of State, Home Office, to the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, 22 October 1918, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Edward Smith, ‘Stanley (née Croll Dalgairns), Sofia Annie (1873–1953), police officer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 9 April 2020, (accessed 10 May 2022).

- Letter from Sofia Stanley to the Metropolitan Police Office, 16 February 1921, MEPO 2/2671, The National Archives.

- Edward Smith, ‘Stanley (née Croll Dalgairns), Sofia Annie (1873–1953), police officer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 9 April 2020, (accessed 10 May 2022).

- ‘Women Police: An Unqualified Success’, Daily Telegraph, 29 July 1920, HO 45/11020/398452, The National Archives.

- Police Orders, 22 February 1927, p. 162, MEPO 7/89, The National Archives; Police Orders, 1 December 1931, p. 1297, MEPO7/93, The National Archives.

- Lilian Wyles’ Annual Qualification Report, 1937, MEPO 3/3073, The National Archives.

- Louise A Jackson, ‘Wyles, Lilian Mary Elizabeth (1885–1975), police officer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2010, (accessed 17 May 2022).

- Lilian Wyles, Women at Scotland Yard (London, 1952), p. 118.

- Lilian Wyles’ Annual Qualification Report, 1937, MEPO 3/3073, The National Archives.

- Police Orders, 27 December 1922, HO 45/11619, The National Archives.

- Press notice from the Home Secretary, 31 January 1923, HO 45/11619, The National Archives.

- Memorandum on the statement against Sofia Stanley, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Memorandum on the statement against Sofia Stanley, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Letter from the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police to the Home Secretary, 8 July 1922, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Memorandum on the statement against Sofia Stanley, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Statement from Sofia Stanley, 7 July 1922, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.