‘With haversacks, waterbottles, and other impedimenta on their backs, they tramped along four abreast, bearing banners appealing for “Direct Government Support” and “No Charity,” to the tunes of marching songs, the playing of bugles, and the shrill notes of the pipes of the various bands of ex-Service men who accompanied them.’

‘Blind Men’s March: Two Hundred Miles Journey Ended’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 26 April 1920, p. 5

On 5 April 1920, members of the National League of the Blind (NLB) set off to march 200 miles to raise awareness of the lack of support for blind people. The above quote taken from the Birmingham Daily Gazette describes their journey, which became known as the 1920 Blind March.

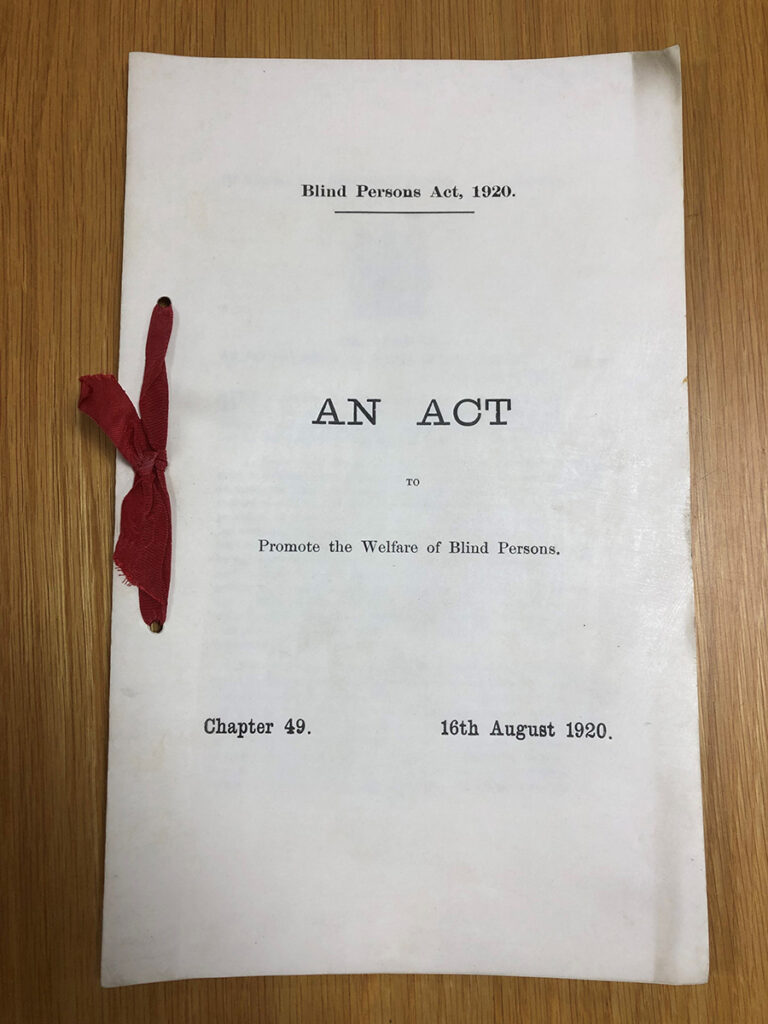

Drawing on the records held at The National Archives, this blog post tells the story of the 1920 Blind March and the subsequent passing of the 1920 Blind Persons Act. This act was the world’s first disability-specific legislation. 16 August 2022 marks the 102nd anniversary of the act receiving Royal Assent.

The establishment of the National League of the Blind

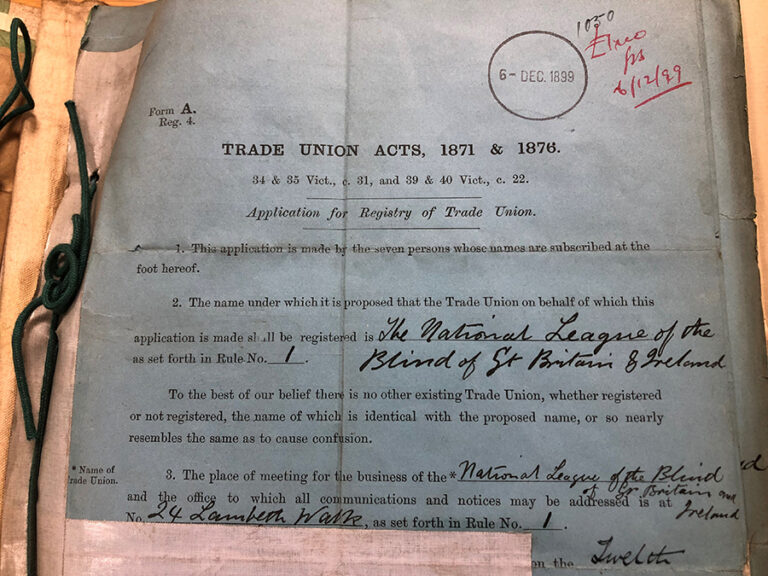

The NLB was established in 1893, and later registered as a trade union in 1899. This record shows the NLB’s application to become a trade union.

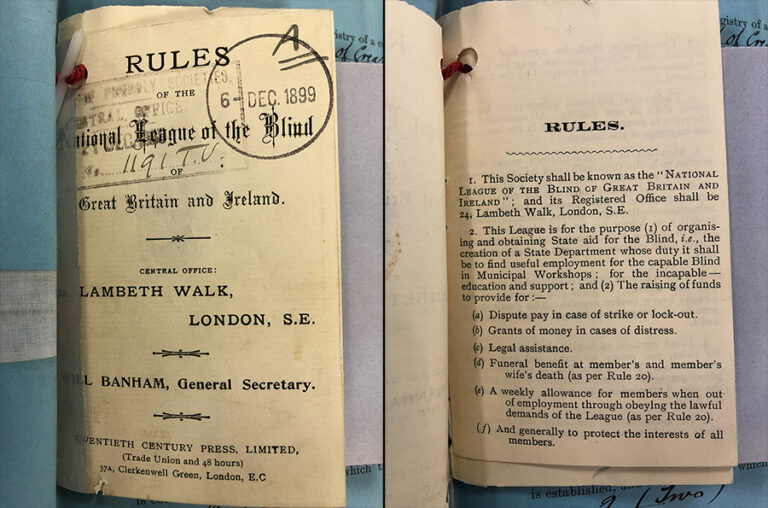

Founded by Ben Purse, the NLB campaigned for the state to take over the responsibility for the employment of blind workers or provide an adequate pension for those who were unable to work. The aims of the NLB can be further seen in this booklet which outlined the rules of the trade union:

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, various charities undertook welfare work for the blind, but they often lacked sufficient resources. By the time the NLB was established, blind people were entering employment in larger numbers, and working in trades such as basket weaving, piano tuning and rug making (see footnote 1). However, wages tended to be low and working conditions were often poor.

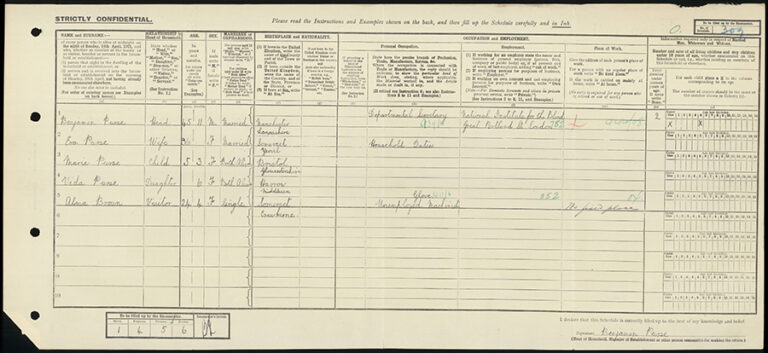

Purse lost his sight completely at the age of 13; he worked as a piano tuner and trained at Henshaw’s Blind Asylum. He is recorded in the 1921 Census as living at 48 Ruttand Road in Harrow with his wife Eva, and daughters Marie and Vida. By this point, his occupation is listed as ‘Departmental Secretary for the National Institute For The Blind’. On the day of the census, the Purse family also had a visitor staying with them – Alma Broun. The 24 year old is recorded on the census as an unemployed glove machinist, so it is possible that her visit was related to Purse’s trade union work.

After the First World War, the NLB’s cause gained greater public attention, as the number of blind people increased due to the impact of the war.

In 1919, the Labour MP and trade unionist Ben Tillett put forward a Private Member’s Bill which advocated for increased support for blind people, but it was unsuccessful. This was the third attempt to introduce legislation to improve the lives of blind people.

The March

Members of the NLB set off on 5 April 1920 from three different locations (Leeds, Manchester, and Newport) and marched to Trafalgar Square in London. Carrying a banner which read ‘Justice Not Charity’, 171 members took part in the march (footnote 2).

A printed circular produced by the NLB stated that the marchers aimed ‘to direct public attention to their case and create that volume of public opinion which would influence the Government to accept responsibility for the direct maintenance of the Blind from public funds.’ (footnote 3) They also hoped to secure a personal interview with the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, in addition to raising funds during the march via street collections (footnote 4).

Men of all ages took part in the march and ‘a long rope ran the full length of the column, and with this the men kept touch with one another.’ (footnote 5) Described as ‘dusty and weather-stained’, the marchers ‘maintained the best of spirits, and expressed great hope for the success of their enterprise.’ (footnote 6)

The march was followed intently by both the local and national press. Indeed, the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer stated that ‘the nearer the men approached London the greater the crowd to see them, the louder the cheering, and the more numerous the bodies of sympathisers who met them.’ (footnote 7) The marchers relied on fellow trade unions and co-operative societies to provide accommodation for them along the route.

On 25 April, the marchers arrived at Trafalgar Square in London and were met with ‘a rousing welcome’ by a crowd of 10,000 people (footnote 8). Various speeches were given by trade unionists where they ‘demanded justice for the blind’ (footnote 9). Five days later, Purse was granted an address with Lloyd George to discuss greater support for blind people.

The passing of the 1920 Blind Persons Act

The 1920 Blind March played an instrumental role in securing legislative changes. Discussing the outcome of the Blind March, the NLB declared that ‘the effort was highly successful, and secured the passing of the Blind Persons Act 1920 which placed the responsibility upon County Councils, and County Borough Councils to make provision for the blind within their respective areas.’ (footnote 10)

The Blind Persons Act was first debated on 26 April and subsequently received Royal Assent on 16 August. The act reduced the pension age for blind people from 70 to 50 and required local authorities to promote the welfare of the blind. Councils were also expected to ‘provide and maintain or contribute towards the provision and maintenance of workshops, hostels, homes, or other places for the reception of blind persons’ (footnote 11).

Although the passing of the 1920 Blind Persons Act is a significant milestone in history, it must be acknowledged that the act was disappointing for some. Much of the responsibility was placed on local authorities, some of whom did not always provide the necessary services, and there were debates as to what constituted blindness in order to be eligible to claim the pension. A subsequent blind march was also held in 1936, which aimed to reframe the government’s policy on state support for the blind. Nonetheless, the 1920 Blind March and the passing of the 1920 Blind Persons Act is an important landmark in the history of disability rights.

Footnotes

- ‘National League of the Blind and Disabled’, Working Class Movement Library (accessed 9 June 2022)

- ‘National League of the Blind and Disabled’, Working Class Movement Library (accessed 9 June 2022)

- Copy of printed circular by the National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, HO 45/16545, The National Archives

- Copy of printed circular by the National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, HO 45/16545, The National Archives

- ‘Pilgrimage of the Blind’, Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 23 April 1920, p. 9

- ‘The Blind Marchers Reach London’, Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 26 April 1920, p. 10

- ‘The Blind Marchers Reach London’, Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 26 April 1920, p. 10

- ‘The March Ended’, Edinburgh Evening News, 26 April 1920, p. 4

- ‘Blind Men In London’, Leeds Mercury, 26 April 1920. P. 1

- Copy of printed circular by the National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, HO 45/16545, The National Archives

- Blind Persons Act 1920, C 65/6417, The National Archives