This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

Much like today, people of the 1920s wanted to have fun. However, one Cabinet minister – Home Secretary William Joynson-Hicks, nicknamed ‘Jix’ – gained a reputation for wanting to restrict that leisure time.

After the strains of the First World War, the nation craved entertainment and throughout the course of the decade the pool of leisure activities greatly expanded. Popular pastimes included going to the cinema, gambling and dancing. For just a couple of shillings you could attend a dance at your local town or village hall and, in a move away from previous ideas of respectability, it became the norm for young women to attend dances together in groups.

In cities, however, there was also the lure of the nightclub, their popularity only enhanced by the glitz and glamour of celebrities and the aristocracy frequenting them. By 1925 there were 11,000 nightclubs in London alone (see footnote 1).

Despite most being law-abiding, there were many nightclubs which operated outside of the law such as the 43, the club we have recreated in our recent exhibition ‘The 1920s: Beyond the Roar’, owned by the ‘Nightclub Queen of Soho’, Kate Meyrick. Kate frequently broke licensing laws and sold alcohol outside of the permitted hours or without a licence – the latter often because her licence had been revoked as a punishment for breaking the law.

While the public was fascinated to keep up-to-date with her activities in the press, for some in society Kate’s antics were more than misdemeanours to be expected with a nation revelling in their leisure time after the devastation of war. Clubs themselves, and the large amounts of alcohol consumed within them, were seen as a threat to public morality and a vocal minority campaigned to curb them. One such person was William, and he was in a position to act.

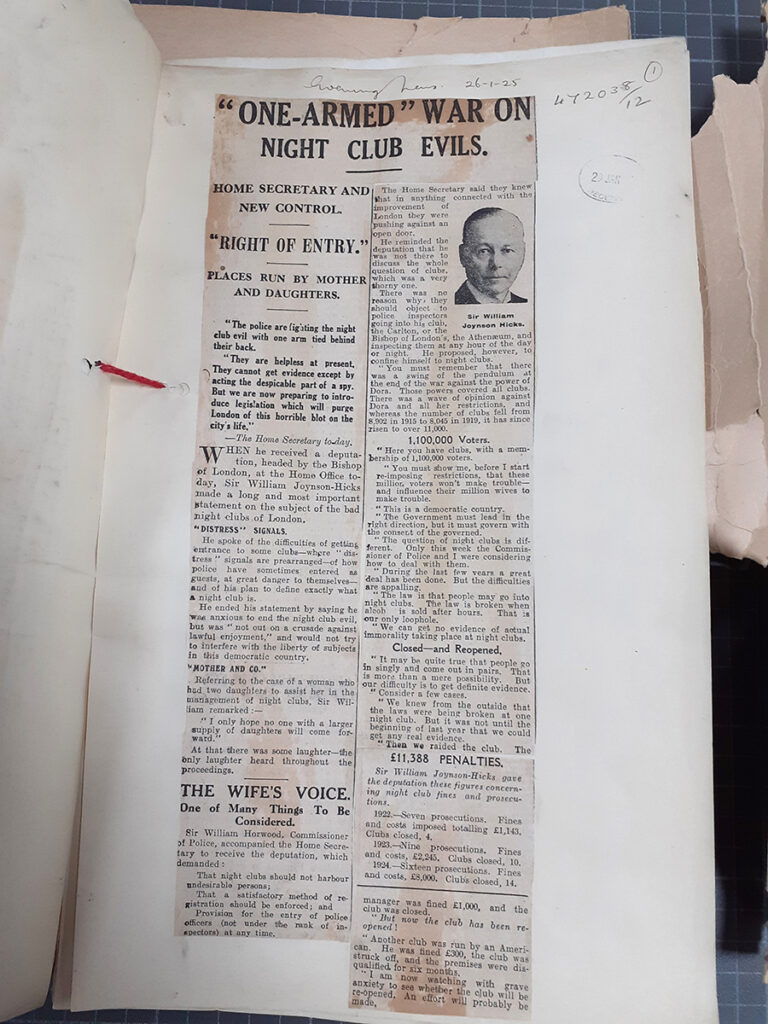

Fuelled by the tabloids who pitted him against Kate, during his tenure as Home Secretary from November 1924 to June 1929 William was in a well-publicised ‘“one-armed” war on night club evils’.

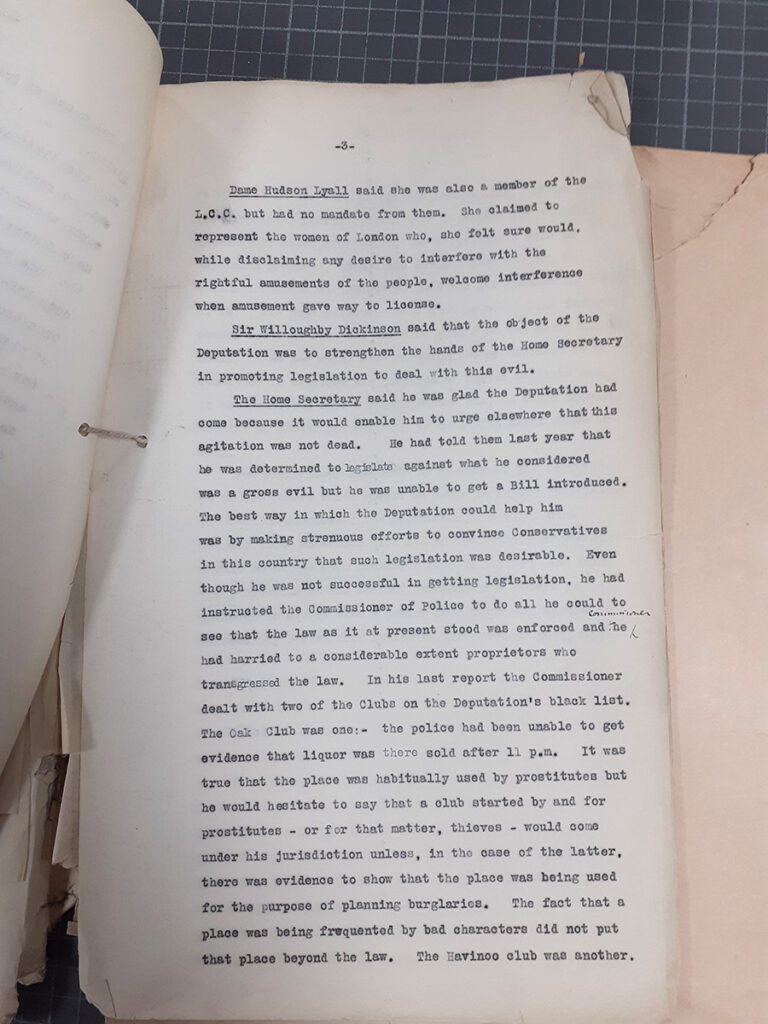

The ‘war’ transcended the pages of the tabloid stories and was a cause that William relentlessly championed, often meeting with like-minded campaigners. On 17 November 1925, The Home Secretary received a deputation from the London Public Morality Council which was made up of representatives of various religious and secular organisations. The write up of the private meeting held at the Home Office reveals that a representative of the Bishop of London began the deputation by attempting to classify nightclubs into three categories:

(1) reputable clubs, which people frequented for an evening’s innocent amusement; (2) border line clubs which on the whole preferred to keep within the law and (3) disreputable clubs which were frequented by disreputable people

Catalogue ref: HO 45/16205

The deputation records then go on to reveal William’s actions thus far since becoming Home Secretary, including a thwarted attempt to introduce a Bill in Parliament against ‘what he considered to be a gross evil’ (footnote 2).

Despite these efforts to introduce legislation, a push by the Metropolitan Police and the continued lobbying of those in power by morality campaigners, only ‘sixty-five clubs were prosecuted between 1924 and 1929, chiefly for selling alcohol out of hours’ (footnote 3).

While his modest success would have been welcomed by campaigners, William’s crackdown on nightclubs ensured that today he is described as ‘deeply unpopular and puritanical’ (footnote 4). This is in part because night-time entertainment was not the only aspect of society which William as Home Secretary tried to curb; he was also involved with the censorship of the 1928 novel ‘The Well of Loneliness’. The book, written by Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall, chronicled the life of Stephen Gordon, a masculine lesbian who identifies as an ‘invert’. In this case William was perhaps more successful – the book was ruled as ‘obscene’ and not published in the UK again for 20 years.

Though William’s ‘war on night club evils’ was demonstrably unsuccessful, it has provided a substantial archival legacy. Without the Metropolitan Police and Home Office documents held at The National Archives about nightclubs, we wouldn’t have detailed insights into the operations, clientele and staff of London’s thriving nightlife scene. It is these records that we have been able to use to re-create the 43 for our exhibition and build a picture of a space that was as infamous for flouting licensing laws as it was famous for its atmosphere.

You can read more about the 43 on our 20sPeople portal where you can also book tickets to experience A Night at the 43.

Footnotes

- Martin Pugh, ‘We Danced all Night: A Social History Between the Wars’, Vintage (2009), p. 218

- The National Archives, HO 45/16205, deputation to the Home Secretary 17 November 1925

- Pugh, p.218

- Judith R Walkowitz, ‘Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London’, Yale University Press (2021), p.211

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

My grandmother, an actress (b.1895) worked for Kate Meyrick some time prior to 1921/2. I’m guessing she worked in one of Kate’s clubs as a “hostess”.