This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

Entertainments at the 43 Club

At midnight on Saturday 17 December 1927 an undercover police officer, Frederick Broomfield, arrived at the 43 Club (then named the Cecil Club) to gather information about ‘the alleged illegal sale and supply of intoxicating liquor’. The 43 Club was a notorious nightclub located in Gerrard Street in the West End of London, operated by ‘Nightclub Queen’ Kate Meyrick. While Broomfield found no evidence of the consumption of alcohol during this undercover observation, he did report that the basement was used for dancing and at the far end of the room a band of five was performing, including the piano, violin, saxophone, banjo and drums (see footnote 1).

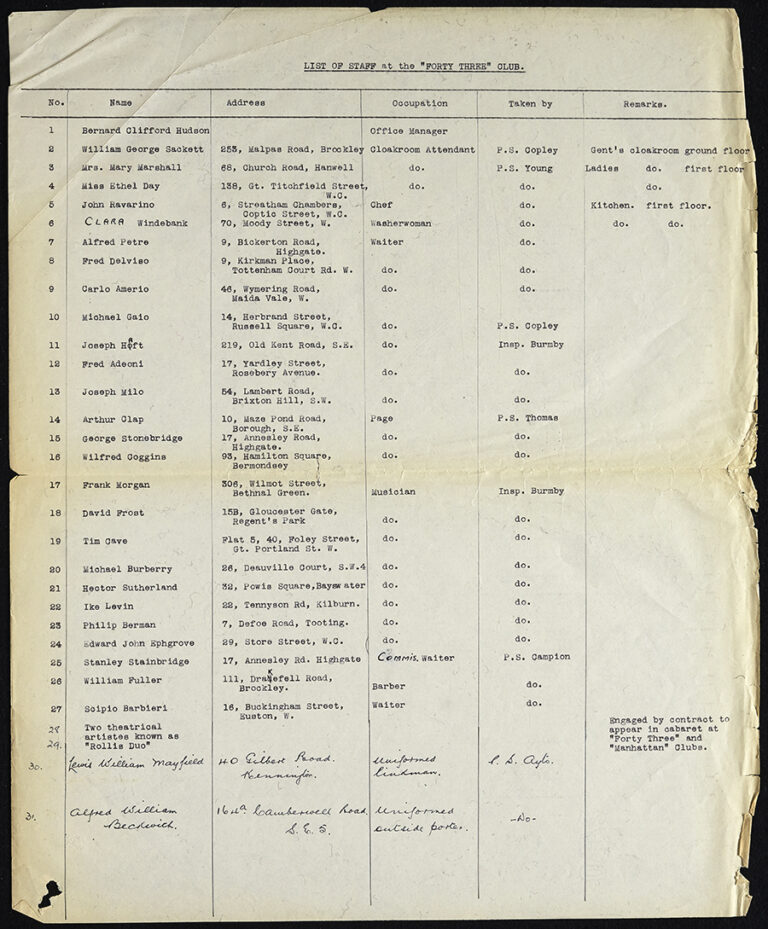

In another document, produced after a police raid on the club the following year, we learn the names and addresses of eight musicians who were performing on that particular night as well as ‘two theatrical artistes known as “Rolls Duo”’ who were noted as having been ‘engaged by contract to appear in cabaret at “Forty Three” and “Manhattan” Clubs’ (footnote 2).

The 43 had a regular rotating programme of performances from a variety of different acts. Police records give us tiny glimpses into what these entertainments might have been like and the performers who were involved. It was at nightclubs such as the 43 that the ‘bright young things’ with disposable incomes could discover the new styles of music and try out the new dances which were booming in popularity in the decade.

But it was not only the rich who were embracing new styles of music and dance. Dances took place all over the country in venues from village halls and pubs to specially built dance halls and Palais de Danse. Jazz and dance bands would be hired for these dances which had varying entrance fees and membership rules, meaning all but the very poorest were able to take part. Young women in particular revelled in the new dance scene, which offered newfound opportunities to socialise with their peers and meet potential romantic partners.

The American influence

Dancing had long been a popular pastime in Britain, but what set the music and dance scene of the 1920s apart was the American influence. Change was already in the air in the first two decades of the 20th century as ragtime and jazz emerged and grew in popularity. These music genres were created by African-American communities and marked a clear break from styles of popular music of the 19th century. They emphasised syncopated rhythms and improvisation and they didn’t require traditional formal musical training, thus opening up the scene to small amateur groups (footnote 3).

In the 1920s, jazz grew in popularity and fully entered the British popular music scene. Musicians travelled to Britain from the USA to perform on the club circuit. This influx of musical performers from abroad sometimes caused concern among British musicians’ unions and The National Archives holds records relating to the immigration and taxation of foreign musicians.

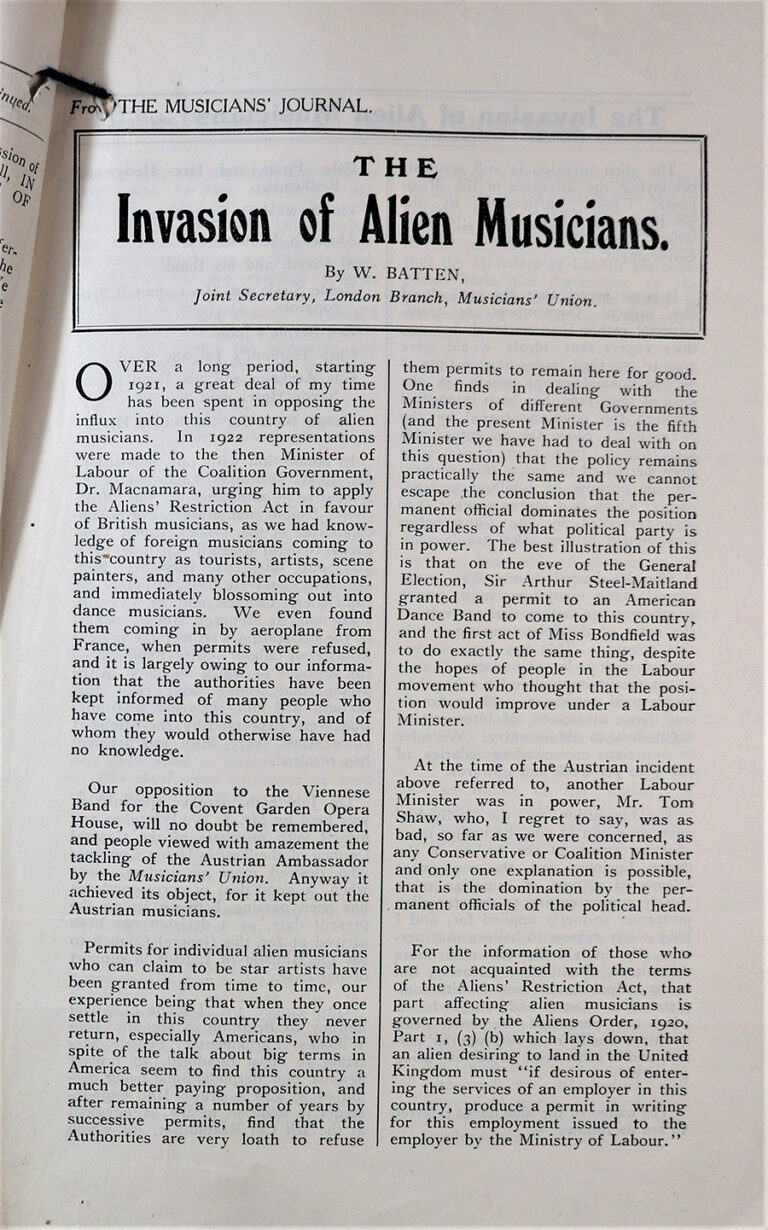

In a 1929 article published in The Musician’s Journal, the Joint Secretary of the London Branch of the Musicians’ Union complained about musicians coming from abroad to work in Britain:

‘Permits for individual alien musicians who can claim to be star artists have been granted from time to time, our experience being that when they once settle in this country they never return, especially Americans, who in spite of the talk about big terms in America seem to find this country a much better paying proposition, and after remaining a number of years by successive permits, find that the Authorities are very loath to refuse them permits to remain here for good.’

W Batten, ‘The Invasion of Alien Musicians’, The Musician’s Journal. Catalogue ref: LAB 2/1188/EDAR528/2/1929

This article discusses ‘alien’ musicians. At the time ‘alien’ was a term officially used to refer to a person who was born outside the United Kingdom and did not have British parents.

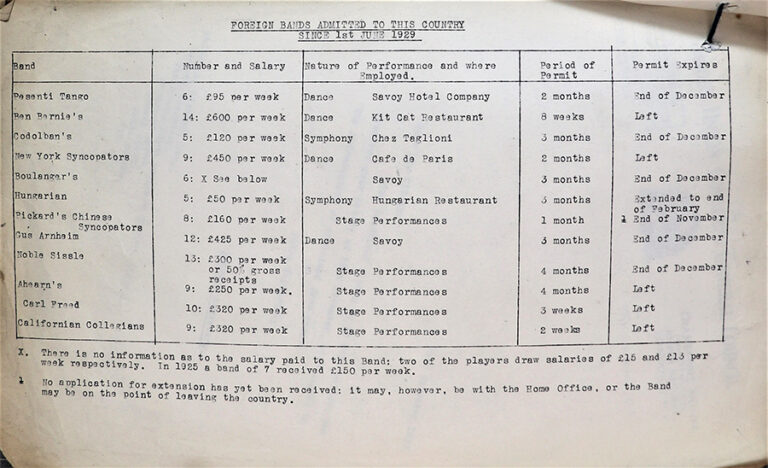

Ministry of Labour records show similar concerns and monitoring of musicians. One document contains a list of foreign bands admitted to Britain in the first half of 1929. Again we get an insight into the bands working in the UK at the time and the venues at which they were playing. These include the New York Syncopators at the Café de Paris and Gus Arnheim at The Savoy. Other notable names include Noble Sissle and Ben Bernie (footnote 4).

Racism and reaction

The jazz music that arrived from the USA was not universally celebrated. Some groups in Britain exhibited racist attitudes towards African-American music, viewing it with suspicion and questioning the morality of this free and expressive style of music. The popularity of the music could not, however, be ignored, so British musicians focused on adapting it to make it more formal and sentimental. The term ‘jazz’ was sidelined in favour of terms like ‘modern rhythmic music’ and ‘syncopated music’. These trends were encouraged by the BBC, which established its own Dance Orchestra to play this new form of ‘British dance music’ (footnote 5).

A similar struggle was taking place as new dance steps from the USA took the nation by storm. A variety of new dances arrived to accompany the new styles of music, and many of these steps allowed dancers much more freedom for self-expression than had ever been possible before. The Charleston, which is thought to have originated from the 1923 Broadway musical Runnin’ Wild (footnote 6),was the most successful of these dances, with Charleston competitions popping up all over the country. It was the youthful energy of the dance that made it so popular.

For many of the same reasons it was popular, the Charleston was condemned by traditional dance instructors and associations. It was said to be immoral and vulgar and even dangerous, with the kicking action in particular being criticised. Dance professionals were particularly critical of the fact that many people were enthusiastically attempting the dance without proper formal instruction (footnote 7). As with music, there were also racist aspects to the criticism of dance as again some condemned the African-American influence. Writing in the Dancing Times in 1927, F A Hadland argued that any new African-American dance ‘had to be refined and adapted to civilized life before it could be countenanced in European ballrooms’ (footnote 8).

The British Association of Teachers of Ballroom Dancing and the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing tried to control dances and standardize steps for more ‘respectable’ dances such as the Foxtrot, Quickstep and Waltz. In 1926, the Charleston was actually banned by London’s Piccadilly Hotel, followed by many other venues. However, the British public could not be convinced, and the dance remained popular throughout the 1920s (footnote 9).

Public dances and moral panic

The concerns over the inherent morality of certain music and dance steps can be clearly found in newspapers and particularly in the music and dance press of the time. However, records of the Home Office held at The National Archives show us certain attitudes to music and dance exhibited on a more mundane local level.

Most complaints relating to music and dance culture in the period relate to concerns about the consumption of alcohol, loose morals and noise, particularly on Sundays. Restrictions on the sale of alcohol and on the running of public dances were quite strict in the 1920s, and one can find correspondence about this from all over the country.

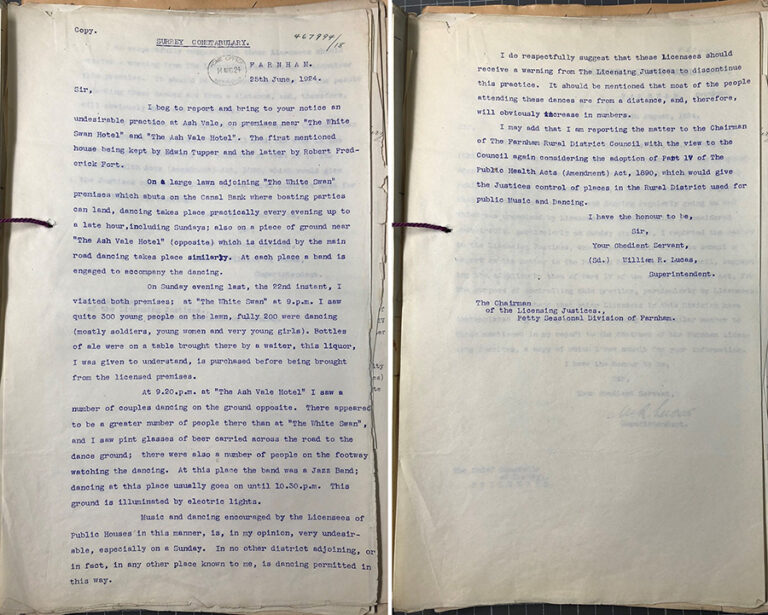

In a letter dated 25 June 1924, William R Lucas, Superintendent of the Surrey Constabulary, complains about dances taking place outside public houses in the area. He writes that on visiting The White Swan Hotel:

‘I saw quite 300 young people on the lawn, fully 200 were dancing (mostly soldiers, young women and very young girls). Bottles of ale were on a table brought there by a waiter, this liquor, I was given to understand, is purchased before being brought from the licensed premises.’

Letter from William R Lucas, 1924, ‘ENTERTAINMENTS: Licensing of premises in rural areas used for public music and dancing’. Catalogue ref: HO 45/20054

At The Ash Vale Hotel:

‘There appeared to be a greater number of people there than at “The White Swan”, I saw pint glasses of beer carried across the road to the dance ground; there were also a number of people on the footway watching the dancing. At this place the band was a Jazz Band; dancing at this place usually goes on until 10.30pm. This ground is illuminated by electric lights.’

In another letter from Derbyshire Constabulary, dated 28 January 1921, Superintendent C A Stone writes about ‘Long Evenings’ held in the Club Room of public houses in Bakewell which last until 2am in the morning, arguing they are ‘liable to grave abuse’. He also states however that, since alcohol was not being served and rules on opening hours were not being broken, ‘nothing could be done’ (footnote 10).

Some in society were clearly worried about the increasing social freedom being embraced by young people, and new styles of music and dance were seen as part of this change and potentially a bad influence. The law could only go so far however in curbing these developments and social and cultural change in the 1920s was an unstoppable force.

Footnotes

- The National Archives, ‘Undercover police observation report’, 17 December 1927. Catalogue ref: HO 144/17667.

- The National Archives, ‘List of staff at the Forty Three Club’, 1928. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/4481.

- James Nott, ‘Contesting Popular Dancing and Dance Music in Britain During the 1920s’ (2013), Cultural and Social History 10:3, 439-456, DOI: 10.2752/147800413X13661166397300.

- The National Archives, ‘Foreign bands admitted to this country since 1st June 1929’. Catalogue ref: LAB 2/1188/EDAR528/2/1929.

- James Nott, ‘Contesting Popular Dancing and Dance Music in Britain During the 1920s’ (2013), Cultural and Social History 10:3, 439-456, DOI: 10.2752/147800413X13661166397300.

- Allison Jean Abra, ‘On With the Dance: Nation, Culture, and Popular Dancing in Britain, 1918-1945′ (2009) [thesis], University of Michigan, p. 65.

- Allison Jean Abra, ‘On With the Dance: Nation, Culture, and Popular Dancing in Britain, 1918-1945′ (2009) [thesis], University of Michigan, p. 66.

- James Nott, ‘Contesting Popular Dancing and Dance Music in Britain During the 1920s’ (2013), Cultural and Social History 10:3, 439-456, DOI: 10.2752/147800413X13661166397300.

- James Nott, ‘Contesting Popular Dancing and Dance Music in Britain During the 1920s’ (2013), Cultural and Social History 10:3, 439-456, DOI: 10.2752/147800413X13661166397300.

- The National Archives, Letter from C A Stone, 1924, ‘ENTERTAINMENTS: Licensing of premises in rural areas used for public music and dancing’. Catalogue ref: HO 45/20054.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

I am particularly interested in the 1920’s fashion as I am looking for a dress to wear at a wedding. The theme is The ‘Peeky Blinders’ era.

However I am having problems finding this period of fashion anywhere. Have you any idea’s please?.

This article is dope I love the beginning tho with 43 club raid