This blog article is part of the 20speople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

Please note: This blog contains ideas, language and imagery from original records which reflect historical viewpoints and attitudes. Some may be considered offensive. However, we think it important to show them here as accurate representations of the record to help us understand the past.

The practice of eugenics – that is, selectively encouraging people with what are perceived as more desirable hereditary traits to reproduce and discouraging reproduction between those with less desirable traits – was widely discussed in the 1920s, linked to the idea of improving the nation’s ‘stock’.

The term eugenics (from the Greek ‘Good Origin’) was originally coined by Francis Galton in 1883 in his book, ‘Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development’. (Available on Archive.org.) He wrote:

‘Whenever a low race is preserved under conditions of life that exact a high-level of efficiency, it must be subjected to rigorous selection. The few best specimens of that race can alone be allowed to become parents, and not many of their descendants can be allowed to live. On the other hand, if a higher race be substituted for the low one, all this terrible misery disappears. The most merciful form of what I ventured to call ‘eugenics’ would consist in watching for the indications of superior strains or races, and in so favouring them that their progeny shall outnumber and gradually replace that of the old one.’

F. Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (London, 1883), p. 307.

Why was eugenics discussed in the period?

With the development of understandings in the science of genetics and population statistics – alongside conceptions of arbitrary racialized, class-based, and intellectual pseudoscientific categories – there were concerns that medical science and the poor law were helping to keep those deemed weak or undesirable alive.

The early 20th century saw society becoming more concerned with the idea that the populace was degenerating, particularly after the Boer War (1899-1902), which exacerbated concerns when around half of the recruits failed to pass the fitness exams. The period also witnessed a changing relationship between the state and families, with a number of liberal reforms such as the introduction of school meals (1906), medical inspection in schools (1907), the Notification of Births Act (1907), and the introduction of maternity benefits under the National Insurance Act (1911).

With the changing relationship between the state and families and the push for social reform, it was a cultural norm to be discussing ways to improve the population. Many people from all walks of life, with the likes of the clergy, aristocracy, social reformers, conservatives, leading intellectuals and academics of the day, took up eugenic ideas in earnest, reasoning that social problems like poverty, crime, unemployment and mental traits like ‘feeblemindedness’ might be solved by adopting eugenic principles. It is not difficult to find pro-eugenic sentiments from public figures in the period. Indeed, notable supporters included the father of the welfare state, William Beveridge, as well as Winston Churchill (see footnote 1).

Eugenic ideologies could be found across the political spectrum and ideas about how to apply them practically were very diverse. A vast array of popular population improvement societies were founded in the period, such as the Infants’ Health Society (1904), the National League for Physical Education and Improvement (1905), The Eugenics Education Society (1907) and the Women’s League of Service for Motherhood (1910) (see footnote 2). These were generally made up of enthusiastic reformers who saw it as their duty to improve the genetic and moral qualities of the nation, as well as social conditions.

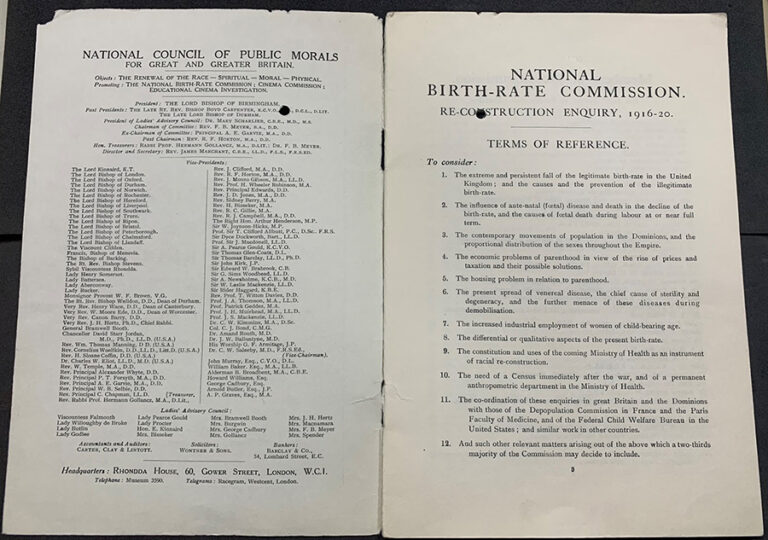

Records held at The National Archives show that some of these types of societies tried to influence state policy. In 1920, the members of the National Birth-Rate Commission (NBC), part of the National Council of Public Morals ‘for Great and Greater Britain’, submitted a report to the Ministry of Health about the moral education of children and the importance of social hygiene for society. The Ministry dismissed them in an internal memo as a ‘self-appointed Committee of earnest people’ (see footnote 3). Members and witnesses of the Commission included the distinguished physician Mary Scharlieb and the birth-control advocate Marie Stopes, as well as numerous Medical Officers of Health and members of the aristocracy.

Racial element of eugenics

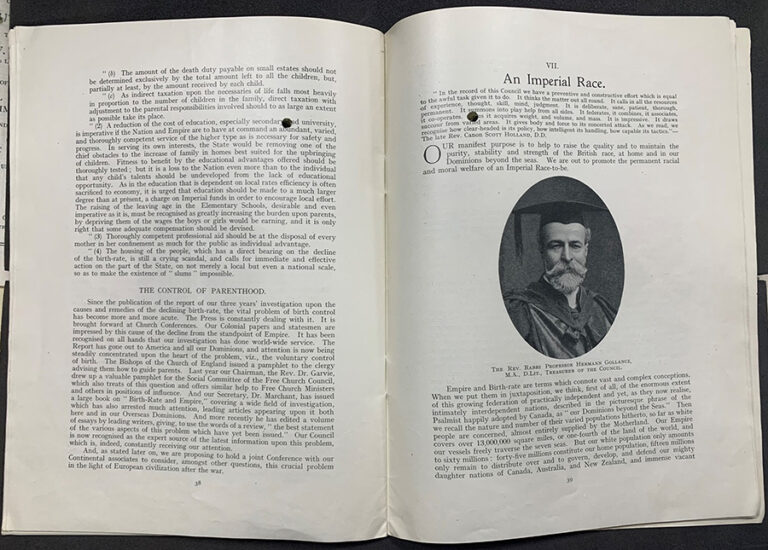

Many of the aims of these types of social improvement societies can be seen as fairly innocuous; the NBC were concerned with the moral influences of the cinema, for example, calling for censorship. Some concerns even led to positive social reforms such as with improvements implemented around mother and child welfare. However, eugenics also gave perceived scientific credibility to fears in 1920s society regarding mental illness, class, migration and race. Indeed, another report of the NBC entitled ‘To Save the British Race’ featured a whole section on the subject of an ‘Imperial Race’, where extreme racist views about the superiority of the white populace were expressed. The report relayed unfounded worries that the white races would be ‘overwhelmed in racial competition’, particularly as the First World War had ‘further depleted the white stocks.’ The NBC stated that:

‘It behoves the white races to end their differences and to unite in establishing durable civilisations which, by reason of moral and intellectual supremacy, will be able to set up a bulwark against the brute force of mere numbers.’

‘To Save the British Race’ Report by the National Council of Public Morals, 1920, p. 41. Catalogue ref: ED 50/47

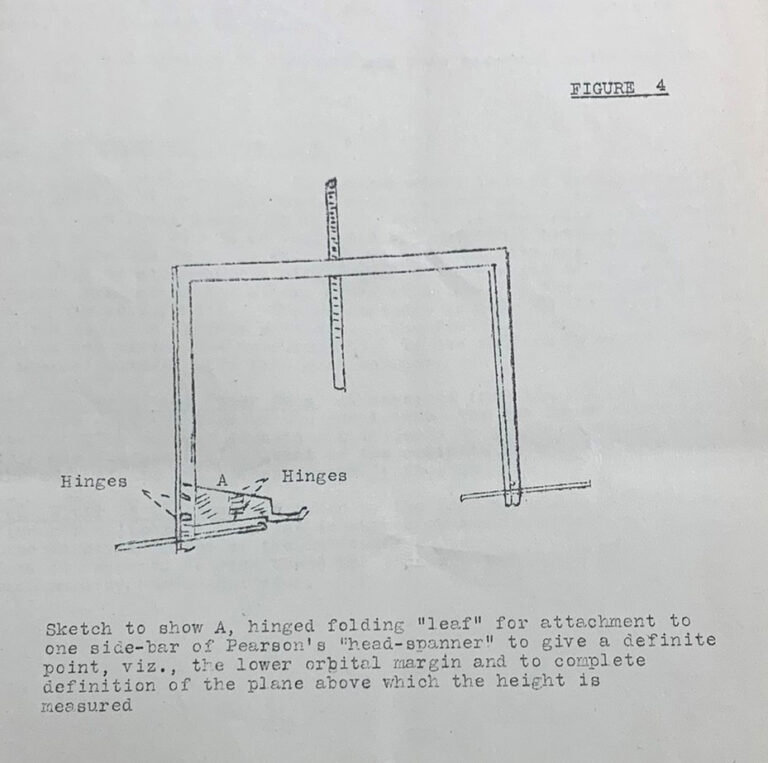

The NBC also strongly argued for the establishment of a permanent Anthropometric Department at the Ministry of Health, as well as a Vocational Bureau (which would advise on fitness for careers), and a General Register of the Population, that would serve to monitor the population more frequently than a decennial census. Essentially, population improvement societies and supporters of eugenics believed that populations should be micro-planned and controlled.

Mental health and sterilisation in the 1920s

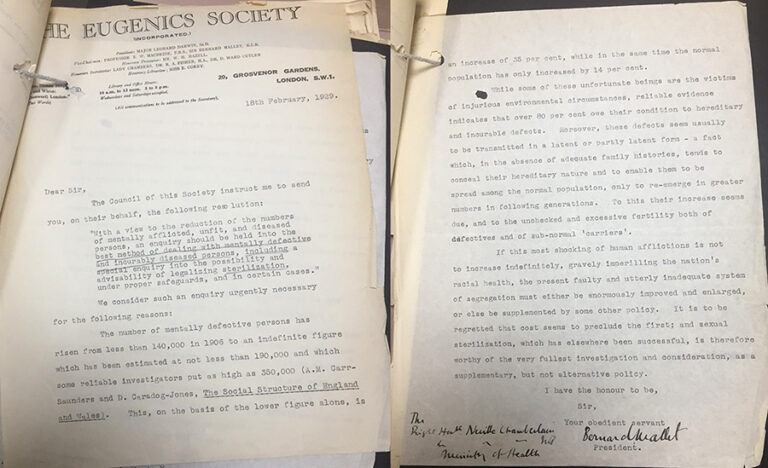

In 1912 the Mental Deficiency Bill was bought before Parliament, with an amendment that would prohibit the marriages between those deemed ‘feebleminded’. The passage was removed before the Bill was passed. However, fears around the so called ‘mentally defective’ procreating continued. Throughout the 1920s, the Eugenics Society called for the Ministry of Health to undertake an enquiry into the ‘best method of dealing with mentally defective and incurably diseased persons’, with the aim of making sterilisation legal.

The National Archives also holds a paper entitled ‘Sterilisation of the Unfit’, which was read by Lord Riddell before the Medico-Legal Society in April 1929. Riddell strongly linked mental ‘defectiveness’ and low intelligence to heredity, raising concerns over the increase of their numbers in the population, claiming that ‘unless we are careful we shall be eaten out of house and home by lunatics and mental deficients’ (see footnote 4). Modern life and urbanisation was blamed:

‘It may be that for the first time in the history of this country the distribution of the population, due to the phenomenal industrial developments of the last century, has become such as to make intensive inbreeding of poor human stock possible on a relatively large scale.’

Lord Riddell, ‘Sterilisation of the Unfit’, p. 7.

Riddell argued for sterilisation of the ‘mentally diseased’, reasoning that ‘… had the six mentally defective parents been dealt with under the Mental Deficiency Act early in life and segregated, the community would not have had to support twenty-nine other mentally defective persons’ (see footnote 5). He also expressed concerns that the rising popularity of birth control would stop ‘highly educated normals’ from procreating (see footnote 6).

Ultimately, the state did not pass eugenic-inspired legislation that interfered with an individual’s right to breed. Other countries, with the likes of the USA, Sweden, and Nazi Germany, implemented eugenic policies like forced sterilisation in the 20th century. However, records show that the British government corresponded with groups who favoured sterilisation throughout the 1920s, and the early 1930s even saw the formation of a Departmental Committee on Sterilisation.

- Papers of the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation (1932-1933) can be found in MH 51/208-211 and the proceedings of the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation (1932-1933) in MH 51/212-235, organised by date.

- Papers of the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation (1928-1935), including discussions about sterilising ‘mental defectives’ can be found in MH 58/100-105.

The existence of these files highlights the range of attitudes of people living in the 1920s towards mental health, poverty, the lower-classes, and race, as well as the wide-ranging influence of eugenic ideas on society and governance.

Further reading

Adam Rutherford, ‘Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics’ (Orion Publishing Co, 2022).

D A Mackenzie, ‘Statistics in Britain 1865-1930: the social construction of scientific knowledge’ (Edinburgh University Press, 1981). Available in the library, shelf mark 306.45 MACK.

Angela Saini, ‘Superior: The Return of Race Science’ (Beacon Press, 2019).

G R Searle, ‘Eugenics and politics in Britain 1900-1914’ (Noordhoff International Publishing, 1976). Available in the library, shelf mark 363.92 SEA.

R A Soloway, ‘Demography and degeneration: eugenics and the declining birthrate in twentieth century Britain’ (University of North Carolina Press, 1990). Available in the library, shelf mark 303.6340941.

J Weeks, ‘Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800’ (Essex, Longman Group Limited, 1981). Available in the library, shelf mark 306.7 WEE.

See our research guides to lunatic asylums, psychiatric hospitals and mental health and Public health and social policy in the 20th century on how to search for records related to some of the themes touched on in this blog.

Footnotes

- G Jones, ‘Eugenics and Social Policy between the Wars’, The Historical Journal, 35, No. 3 (Sep, 1982), pp. 717-728.

- J Weeks, ‘Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800’ (Essex, Longman Group Limited, 1981), pp. 26-27.

- ED 50/47, Memorandum relating to the Report of the Presentation of the Second Report to the Minister of Health, internal reference M198/23, 1920.

- MH 58/103, Lord Riddell, ‘Sterilisation of the Unfit’, 25 April 1929, Riddell, pp. 18-19.

- Riddell, p. 6.

- Riddell, p. 25.

I bceame horribly familiar with the eugenics approach in reading how Germany was eliminating ie, killing, those such as the insane, the physically deformed, communists, and Jews, even before the war. And again, while working with Home Children records. It all sickened me to realize the extent to which the eugenics movement influenced the new occupation of social worker, even in Canada.

As per an article on the Queen’s College Journal, in 1888 pgs164-165. “….. But we all know that very many, if not the majority of these pauper children, carry with them inherited tendancies both physical and moral which no training, however careful, can eradicate and which may do more harm eventually to the community receiving them than good to the individuals received. Not a few of these imported paupers hjave turned out to veritable plague spots in the physical and moral life of the community. We have already so much of the evil element among us that we cannot afford to receive a very much larger influence of bad blood.”

Cheers anyways, BT