This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

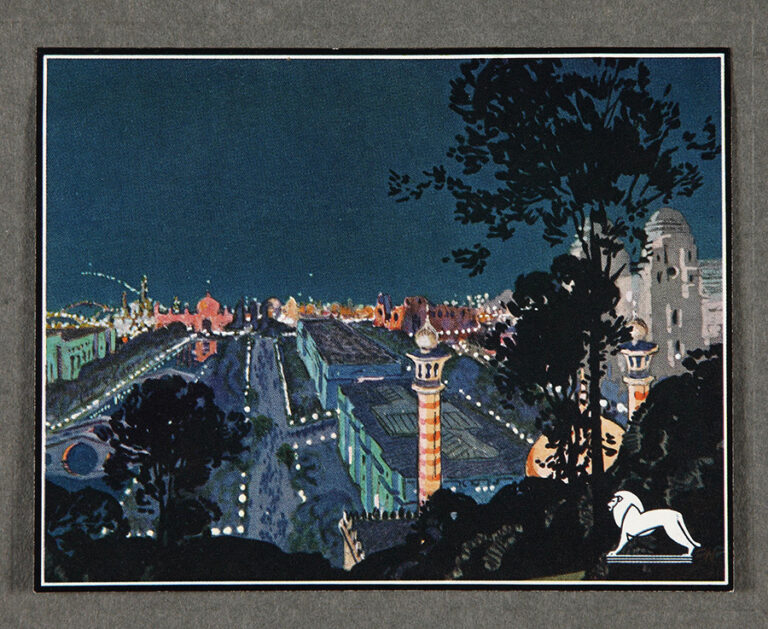

In 1924 an exhibition was held at Wembley Park in London, which aimed to celebrate the British Empire and its economic achievements and potential. It took place at a time when the empire was at its largest, and it was also a time when anti-colonial sentiment was growing. Britain was dependent economically on its empire and was desperate to keep it stable and unified. In this context, the government organised the British Empire Exhibition, which was opened by King George V on 23 April 1924. The exhibition was large, varied and exciting, offering elephants, butter sculptures and miniature railways among much else. It proved popular with the British public, attracting more than 25 million visitors. At the same time however, the planning process was often fraught, and many aspects of the exhibition were criticised. By exploring the British Empire Exhibition and responses to it, we can get an intriguing insight into the complicated nature of the British Empire in the 1920s.

The road to the Exhibition

The British Empire Exhibition was one of several events organised in the early 20th century to promote the British Empire and its industries. In 1909, there had been the Imperial International Exhibition at London’s White City, and in 1911 the Festival of Empire at Crystal Palace. These events were all designed to strengthen and unify the empire, particularly in a context when the British economy was coming under pressure from German and American competition. The idea for a full British Empire Exhibition had been seriously discussed as early as 1913, following a proposal from Lord Strathcona, however it was delayed by the First World War. Finally, in 1919, the proposal for the exhibition was agreed by the government, funding was secured, and an opening date set.

The exhibition was described as a successor to the Great Exhibition of 1851, an event which had become, to some extent, legendary in the eyes of many. But this new event had a much more specific agenda: to bring together only the dominions, colonies, mandates and protectorates of the British Empire, to display their common interests and cooperation, to promote their industries and produce and to encourage Imperial trade[ref]Hughes, Deborah L. ‘Kenya, India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924.’ Race & Class, vol. 47, no. 4, Apr. 2006, p. 67, doi:10.1177/0306396806063858.[/ref].

The aims of the exhibition were described in an official promotional booklet:

It will be in effect an Imperial stocktaking and a vast window display. Those who doubt the Empire’s potentialities, and those who simply do not consider them, will be confronted with a clear sight of what this great community of free nations can produce. More important still, the possibilities which our Imperial resources hold will for the first time be made plain. So much of our trade is placed abroad, not because the Empire cannot in a large measure fulfil her own requirements, but because Britons do not know that they can buy from Britons, and it has not occurred to them to find it out. Now British markets will be brought to them. Raw materials will be shown to those who can make use of them: manufactured goods of every kind to those who have not had the facilities to manufacture.

Promotional booklet for the British Empire Exhibition, 1924. Catalogue ref: HO 45/11509

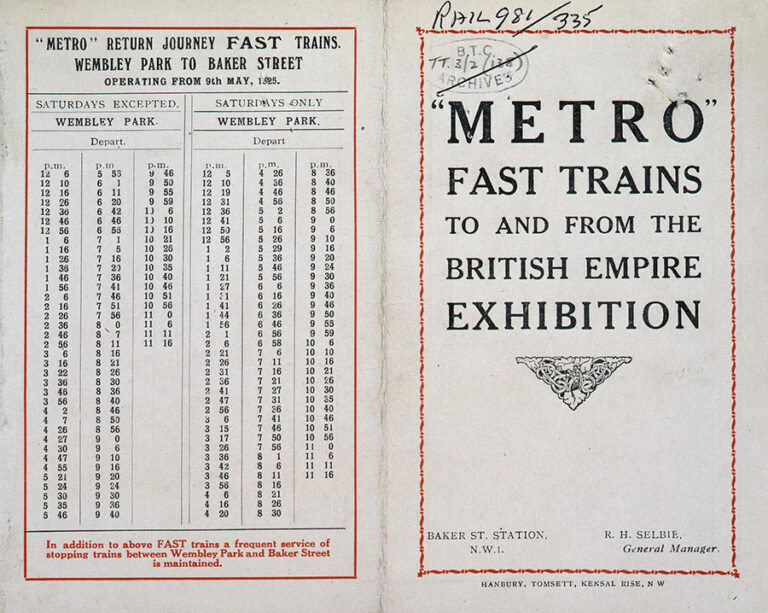

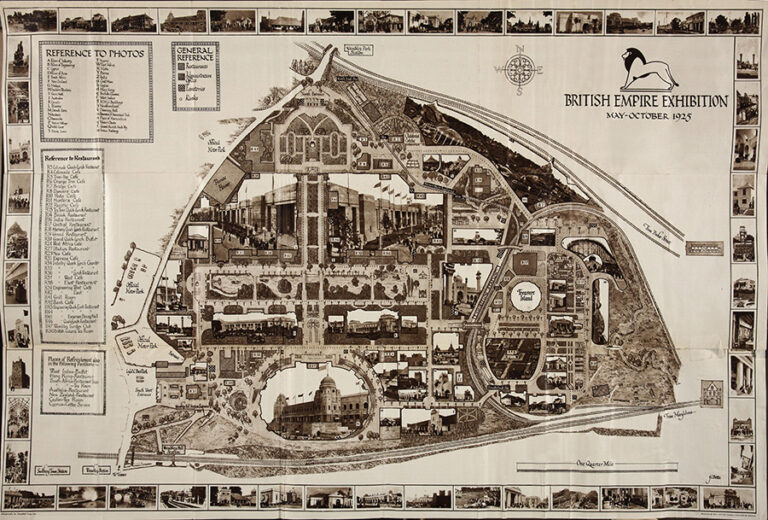

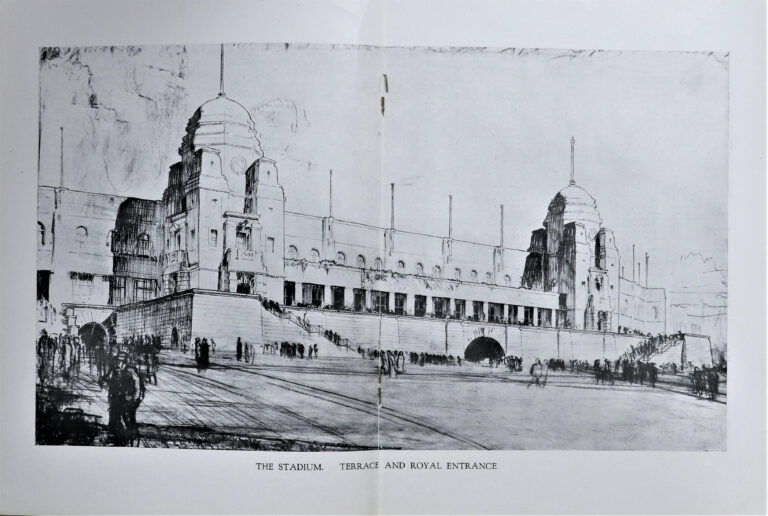

The preparations for the exhibition involved a great deal of development in the Wembley Park area of London. The area had been chosen because it was said to be extremely accessible from all parts of the country, taking only 10 minutes by train from either Marylebone or Baker Street stations[ref]Promotional booklet for the British Empire Exhibition, 1924. Catalogue ref: HO 45/11509.[/ref]. The new Empire Stadium was built especially for the exhibition, roads were widened, and a new railway station was built on the site itself.

‘Exceptionally unfavourable weather’

The Exhibition was opened on 23 April 1924 by King George V and Queen Mary at the Empire Stadium. The King gave a speech on the opening day which was broadcast by the BBC, becoming the first broadcast made by a British monarch on radio. The recording of the speech, held by the British Library and available online, is also the earliest surviving recording of any radio broadcast[ref]’King George V opens the British Empire Exhibition, 23 April 1924’, The British Library, (accessed 12 February 2022).[/ref].

Our heartiest congratulations are due to the board of management, to the executive council, and to all who have worked with and under them for the marvellous organisation and industry which has produced this triumphant result. I am well aware of the numerous adverse circumstances, including the exceptionally unfavourable weather, which have been faced. These were successfully overcome by arduous labours carried out with resolution and goodwill

Extract from the speech of King George V at the opening of the British Empire Exhibition, 23 April 1924

The Exhibition site

Covering over 200 acres, the exhibition site included pavilions displaying the produce, industries and crafts of different colonies and dominions. These were developed and organised by the respective colonial governments. 56 out of 58 territories participated with their displays and pavilions. There were also over 40 different cafes, restaurants and places of refreshment, a children’s crèche and the ‘Treasure Island’ attraction which boasted a miniature train.

Visitors could learn about developments in consumer goods, including fabrics, appliances and processed foods, in the Palace of Industry and explore electrical, automotive and aeronautics industries in the Palace of Engineering. Other exhibits of note include Queen Mary’s famous doll’s house and a butter sculpture of the Prince of Wales in the dairy produce section of the Canada Pavilion[ref]Anne Clendinning, ‘On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25.’ BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. http://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=anne-clendinning-on-the-british-empire-exhibition-1924-25 (Accessed 12/02/2022).[/ref]. The exhibition was open for six months in 1924 and reopened again in 1925. Over the course of its opening, it attracted over 25 million visitors[ref]Jules Skotnes-Brown, ‘From the White Man’s Grave to the White Man’s Home? Experiencing ‘Tropical Africa’ at the 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition’, Spring 2019, Issue 11, Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101.[/ref].

Live animals were also on display, including elephants named Simla and Saucy. On Friday 17 July 1925, reports of an ‘elephant fight at Wembley’ appeared in the press:

An exciting scene was witnessed in the lake at Wembley this week, when three of the Stadium elephants (two weighing five tons each and the other four tons) went there to bathe. Immediately they were in the water Simla, who is 56 years of age, and the youngest of the three, began to attack Saucy. Showers of water rose in all directions, and spectators on the bank fled to avoid being drenched. Desperate efforts had to be made by the attendants to get Simla out of the lake, the fear being what with his tusks, which are of great length, he might kill Saucy. Eventually Simla was coaxed again to dry land, and there consoled himself by lunching substantially of the floral decorations of the lake side.[ref]’Elephant fight at Wembley’, Flintshire County Herald, Friday 17 July 1925, British Newspaper Archive.[/ref]

National pavilions and criticism

The pavilions for individual countries included a variety of displays showcasing produce, crafts and industries. The India Pavilion was modelled on the Jama Masjid in Delhi and the Taj Mahal in Agra and contained 27 courts displaying different products as well an exhibition of Indian art. The organisation of these displays sometimes involved a lot of debate and disagreement, particularly in the context of rising ant-colonial sentiment in some areas of the empire. Indian nationalists called for a boycott of the exhibition and two of the four Indian nationals on the exhibition’s executive council in India resigned[ref]Anne Clendinning, ‘On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25.’ BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. http://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=anne-clendinning-on-the-british-empire-exhibition-1924-25 (Accessed 12/02/2022); David Simonelli, ‘Laughing nations of happy children who have never grown up: Race, the Concept of Commonwealth and the 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition’. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, vol. 10 no. 1, 2009. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/cch.0.0044.[/ref].

One particular practice that was criticised was the display of living people brought over from countries in the empire to participate in the exhibition. This echoed exhibition practices common in the 19th century. Some worked in shops and restaurants connected to their pavilions, and others sat in the displays themselves demonstrating crafts, industries and cultural activities. This practice could be found in the Nigerian Pavilion, where a walled city was built, with displays on metalwork and leatherwork for example. This is well-documented in a photograph album held at The National Archives[ref]The National Archives, ‘NIGERIA 19. British Empire Exhibition, Wembley, 1925. Nigeria Pavillion.’ Catalogue ref: CO 1069/73/15.[/ref].

West African students in London complained about the displays, arguing that they misrepresented their people and culture, presenting them as primitive while ignoring the rapid industrialisation that was actually occurring in the region. Dr Adeniyi-Jones, a member of the Nigerian Legislation Council, said he ‘regretted that the particular form of the Nigerian exhibit that was chosen, merely to show a village without … showing the progress made in Nigerian life as a whole, was to give only a partial and incorrect idea of Nigeria of to-day’[ref]Jules Skotnes-Brown, ‘From the White Man’s Grave to the White Man’s Home? Experiencing ‘Tropical Africa’ at the 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition’, Spring 2019, Issue 11, Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101.[/ref].

Legacies of the British Empire Exhibition

Although popular with most visitors, the exhibition was a financial disaster, making a loss of around £1.5 million by the time it closed on 31 October 1925. Most buildings on the site were demolished, however it was decided to leave the Palace of Industry and the Empire Stadium standing. The Empire Stadium was renamed Wembley Stadium and stood for another 78 years until it was replaced by a new stadium in 2003.

Looking back at the British Empire Exhibition, and all the surprising stories behind it, we can get a snapshot of how the British government wanted the empire to be perceived in the 1920s. And by considering its context and public reception, we can reveal how complicated attitudes to empire really were at this moment in time.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

Great article. A quick correction on 2 sentences.

“The extract is from the speech of King Edward V at the opening of the British Empire Exhibition, 23 April 1924” – it’s George V.

“…becoming the first broadcast made by a British monarch on radio.”

– it’s actually the first broadcast made by any monarch, the world over.

“The recording of the speech, held by the British Library and available online, is also the earliest surviving recording of any radio broadcast.” – There is one earlier one – of President Woodrow Wilson, in Nov 1923. This is likely the second earliest surviving recording – and certainly the earliest surviving BBC recording, the next being not until 1932.

Thoroughly enjoyed the illuminating article – thank you.

Fascinating article, but It should read King George V not King Edward V when referring to the opening speech.

My grand uncle attended this exhibition representative of Government of Mysore (India) in 1924; I do have archives of his visit in the form of letters if you are interested to preserve them as part of the national archives.

Thank you for your comment and this offer. For advice on donating material to The National Archives, please visit our Donating records page.