This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

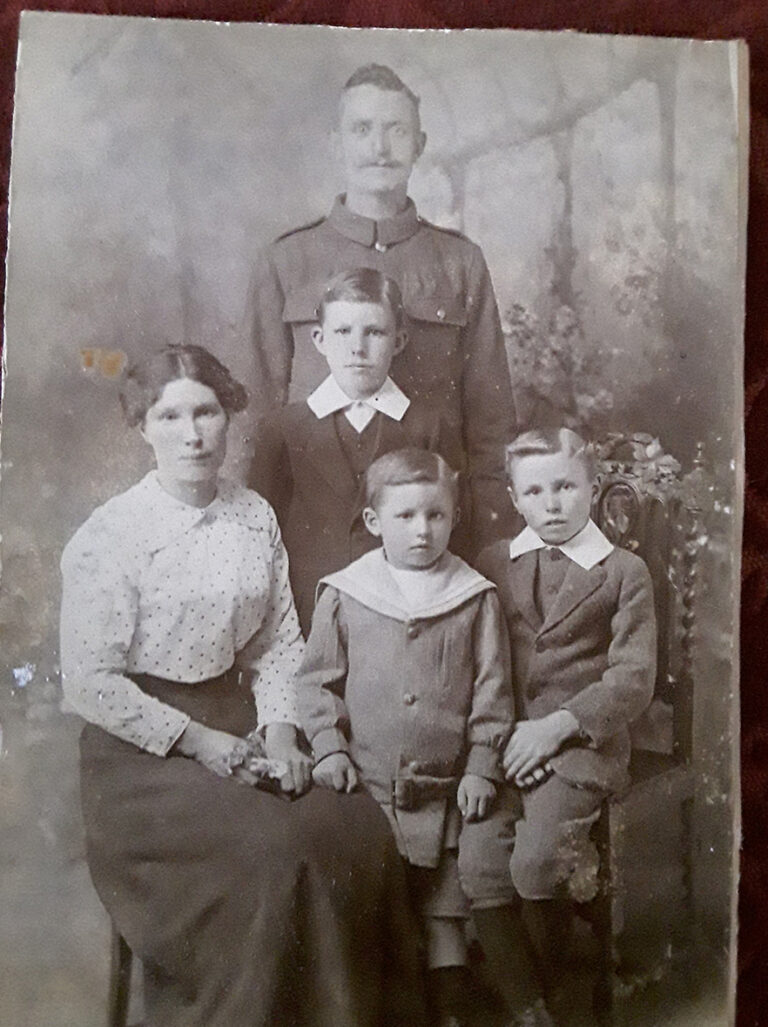

You probably won’t have heard of Edward Sherwood, Lewis Washburn, George Booker or William Bonehill. They weren’t famous, and they didn’t play a defining part in the past. They were a part of their local communities. But sadly the moment at which they left most trace in the archival record came at the end of their lives: the moment of their deaths.

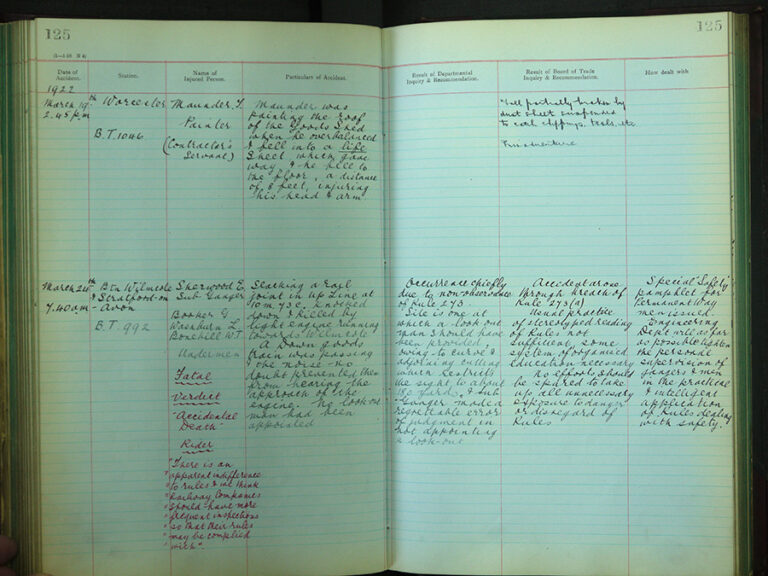

At 07:40 on 24 March 1922, a steam engine hit all four men, who were at work on the railway tracks near Wilmcote in Warwickshire, England. They were Great Western Railway (GWR) workers, employed to maintain the tracks. All four died instantly, on 24 March – exactly 100 years ago at the time of publication.

The men and their families were ordinary ‘20sPeople’: the sorts of individuals that can tell us much about everyday life – and dangers – in the 1920s. Tragically, the accident which killed them was only unusual in that so many employees died at once; usually railway staff accidents affected one or two people. In 1922, for example, 240 railway staff died at work and nearly 16,000 were injured.

In the accident, the four men were working on a curve in the track, maintaining one set of rails as trains passed on the adjacent line. They didn’t have a dedicated team member to watch out for oncoming trains on their line, and were working with backs turned when they were hit. All four men died at the scene; all four were buried at Wilmcote church.

The local press reported the funeral, likely with some hyperbole: ‘the whole line of the route were thronged with people, and several thousand must have watched the procession […] the crowd of mourners included many men and women well over eighty, who moved slowly forward, tears streaming down their wrinkled faces.’ (see footnote 1)

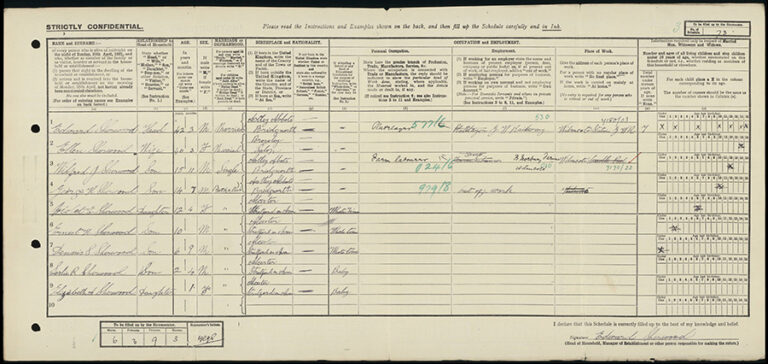

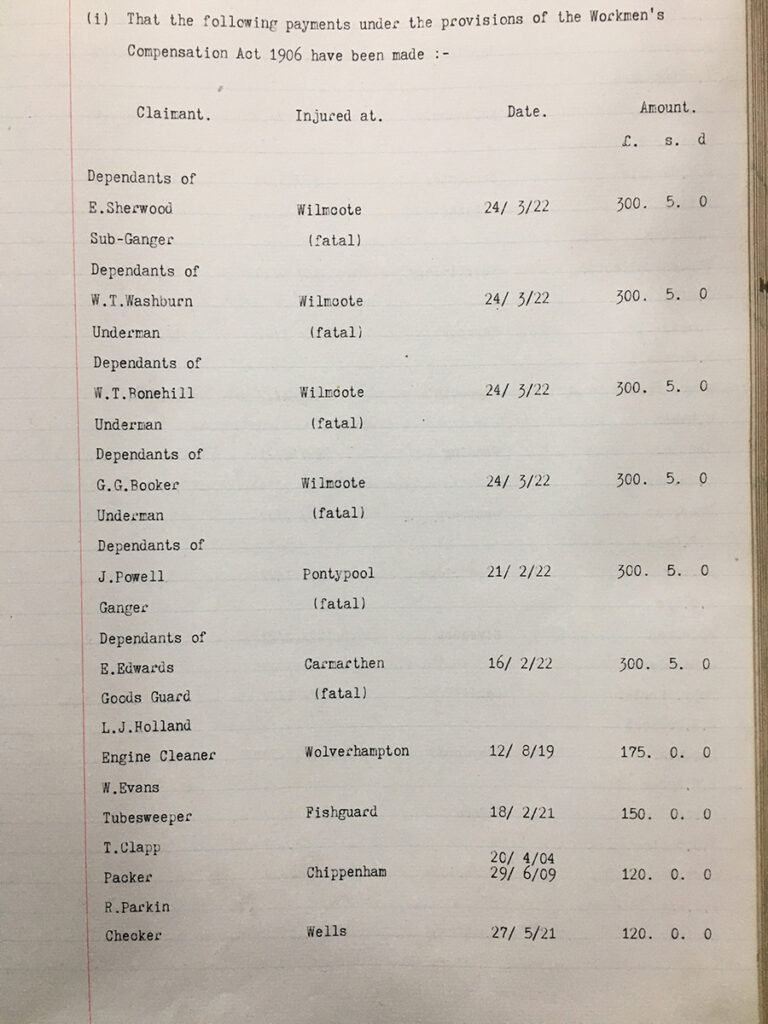

Each man was married, and between them they left 12 children, with a 13th being born a short while after the accident: Winifred Joan Bonehill. The men were the major wage earners in their households, so finances became an issue for all four families. Each family received just over £300 in compensation from the GWR – around £16,700 today. The men’s trade union, the National Union of Railwaymen (now the RMT), provided support, as did the local community: the Mayor of Stratford started a collection, and a concert was held nearby to raise money.

How did the families cope? It’s hard to know for certain, but they appeared resilient; they had to be. At least two of the widowed women remarried. In the late 1920s Ellen Sherwood moved her family to Oxfordshire, where she was a level crossing keeper – it’s possible this job was provided by the GWR, as a means of providing an income for her family after the accident. Tragically, Ellen’s father was to die in an accident at her level crossing in the 1930s. Whether by coincidence or by way of continuing care for the families, several of the children who lost their fathers ended up working on the railways.

Sadly, it seems that working practices did not change as a result of the accident. Similar accidents remained a regular occurrence, as the Railway Work, Life & Death project is uncovering. The hard work of the project volunteers means we can find out more about railway workers as individuals.

One change we do see, following the 1922 Wilmcote accident and the 1921 Stapleton Road accident, in which six men were killed, is a new GWR safety booklet. Aimed at track workers, it advised them on what to do and what not to do, using photos to show ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ actions.

The centenary of the accident is being marked on 24 March, at Wilmcote, including descendants of George Booker, Lewis Washburn and William Bonehill.

Dr Mike Esbester is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Portsmouth, and co-leader of the ‘Railway Work, Life & Death’ project, which explores accidents affecting British and Irish railway staff before 1939. The project is a collaboration between the University of Portsmouth, the National Railway Museum and the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick. The project aim is to make the details of tens of thousands of railway staff accidents freely available to research.

The stories in this blog are only some of the key moments for the men and their families. The project team have produced a series of more detailed blogs about the Wilmcote accident, available here on the Railway Work, Life & Death project blog.

The project is also working with The National Archives to include accident records produced by English and Welsh railway companies; read our previous blog on the subject here: Thumbs up to railway accidents.

Keep up to date with the project on Twitter and Facebook.

Footnotes

- Warwick & Warwickshire Advertiser, 1 April 1922, p.7.

Interesting article, especially as it caught my eye as I am waiting for my train to depart at Stratford-upon-Avon and will shortly pass through Wilmcote.

Hi

Not a speck of forensic evidence in view. Unverifiable third partys going on about what they didn’t see and can’t describe. Were they union men? 8000 turned out to honour accidental nobodies?

I did some volunteer transcriptions of NSW Railway Employee Cards at the State Records Archive of NSW a few years. It was fascinating to see all of the handwritten notes and comments on the cards, and the fascinating stories that they told.