As we all surely know by now, on 11 November 1918 – just over 100 years ago – Germany signed an armistice agreement with France, Britain and the United States, bringing an end to the First World War on the Western Front.

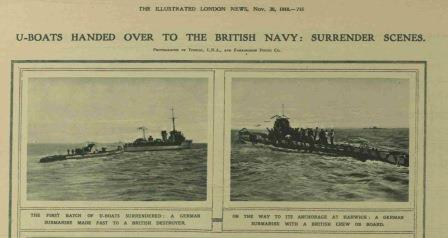

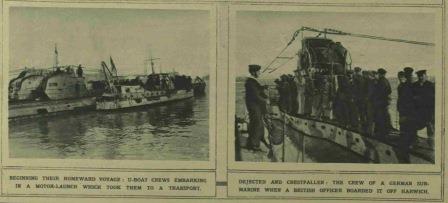

Image of surrendered submarines at Harwich from an article in the Illustrated London News, 30 November 1918. Catalogue reference: ZPR 34/153

The terms of the armistice were, in many ways, punitive to the Germans. In part, the Armistice sought on the British and French part to disarm Germany, in a misguided attempt to ensure that there would be no further outbreaks of ‘German militarism’. This was clear in the Naval terms of the armistice – particularly with regards to submarines, which were to be surrendered in totality. Article XXII of the agreement instructed the German government thus:

To surrender at the ports specified by the Allies and the United States all submarines at present in existence (including all submarine cruisers and mine layers), with armament and equipment complete. Those that can not put to sea shall be deprived of armament and equipment and shall remain under the supervision of the Allies and the United States. Submarines ready to put to sea shall be prepared to leave German ports immediately on receipt of a wireless order to sail to the port of surrender, the remainder to follow as early as possible. The conditions of this article shall be completed within 14 days of the signing of the armistice[ref] An electronic copy of the Armistice can be found here.[/ref]

German submarines had menaced Britain’s naval supply lines during the conflict, causing acute food shortages, as I have previously written. The activities of German submarines – or U-boats, as they were referred to – threatened vital food imports into Britain.

Logo from the National Savings Committee’s ‘Eat Less Bread’ campaign, launched in light of grain shortages cause in part by German submarine activity. Catalogue reference: NSC 7/37

Article XXII of the armistice sought to remove this threat by taking Germany’s submarine fleet away. This, when combined with other clauses in the agreement compelling Germany to turn over much of its surface fleet, too, meant that one of prices Germany paid for peace was the neutralisation of its Navy. Once again, Britain would reign supreme on the seas.

You say you want a revolution

While the Armistice terms were clear, what was less clear was exactly how they would happen – or if it could, for that matter.

By November 1918, Germany was in the grip of a revolution. The Kaiser had abdicated and fled and the government had been overthrown by a coalition of mostly left-wing organisations, led by the ‘centre-left’ Social Democratic Party (SPD) but containing significant communist and anarcho-syndicalist groups. There was a provisional government but it operated in tandem and, to a certain extent, with the consent of myriad workers’ and soldiers’ councils – Russian style soviets who sought a society controlled by workers organised around broadly anarcho-syndicalist principles.

The revolutionary tensions in Germany and her armed forces meant that negotiations of the arrangements of the submarine surrender in the days after the armistice were signed were tinged with uncertainty. On 16 November Eric Geddes, First Lord of the Admiralty, reported to Cabinet about a meeting held between the British Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet and Rear-Admiral Meurer, a senior German naval officer, which demonstrated these difficulties.

Image of surrendered submarines at Harwich from an article in the Illustrated London News, 30 November 1918. Catalogue reference: ZPR 34/153

Meurer had sounded a note of caution. He stated that, while he and his superiors were content to carry out the surrender terms, it was possible that the British did not ‘appreciate the chaotic conditions existing in Germany, which render the execution of the Armistice Terms extremely difficult … action can only be taken with the consent of the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council’.

However, these fears seem to have been misplaced, as Geddes reported that on 15 November that the soldiers’ council of the German Submarine Flotillas had released a communiqué stating that ‘the whole of the crews of Submarine Flotillas conscious of the serious position of the Fatherland and after having striven for their Fatherland for 50 months in need and privation will not refuse to the Fatherland the last and hardest service; they will bring all the Submarines to the place which they are ordered’.[ref] Cabinet Memorandum by Eric Geddes, ‘Compliance with Naval Conditions of Armistice’, 16 November 1918. Catalogue reference: CAB 24/70/10[/ref]

Logistics

With the councils on side, the surrender could proceed. While the surrender of the German surface fleet was planned in haste to take place in the Firth of Forth, Harwich in Essex was chosen to be the place where the submarines would be given up. The details of how this was planned and carried out are detailed in a fascinating Admiralty volume held at The National Archives – ADM 137/2483.

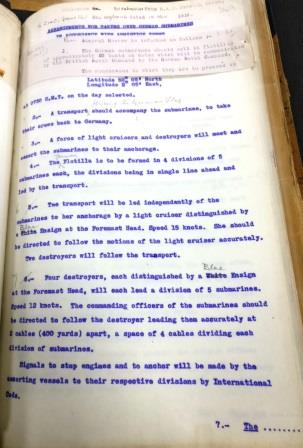

On 18 November, instruction as to how the surrender would take place began to be issued. The German submarines were to gather off the coast of Harwich at the latitude and longitude of 52º05′, 2º05′. The flotillas were to be accompanied by transports, so that the crews could be ferried back to Germany after their war craft had been handed over. The submarines would then be led to Harwich by a force of British destroyers and cruisers.

Once at the surrender anchorage, the German crew of each vessel (except for those who had to tend to machinery) were to parade on the forecastle and await the boarding of a British officer, who would take command of the vessel. On the officer’s arrival, the German officer commanding the submarine was to hand over a full crew list, as well as a signed declaration stating that the submarine was in the following condition:

Instructions for the surrender of submarines at Harwich, 1918. Catalogue reference ADM 137/2483

(1) Batteries fully charged up

(2) Full complement of torpedoes on board, launched back clear of torpedo tubes and without war heads

(3) That no explosives of any sort are on board

(4) That the submarine is in running condition, fully blown

(5) That all of the periscopes are in place, and in working and efficient condition

(6) That all sea valves are closed and in efficient condition

(7) That no infernal machines or booby traps of any sort are on board

With these formalities dealt with, the German crews would leave for motor launches which would take them back to their transport (none set foot on British soil), while the German captain would show the British officer around the submarine, ‘and give him details of his vessel and every facility for taking over’.

The surrender

The surrender began on 20 November 1918, with Admiral Meurer informing the British that 20 submarines would present themselves to be taken over that day.

Over the course of November 1918, a total of more than 160 submarines would give themselves up at Harwich. ADM 137/2483 contains a wealth of information, and crew lists, for many of them.

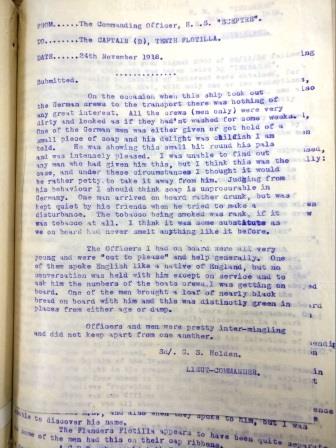

Report on the physical condition of German sailors and submarines by the commanding officer of HMS Sceptre, 1918. Catalogue reference: ADM 137/2483

Also included are reports from the British Naval officers who oversaw the surrender, making comment to the Admiralty on any problems or other things of interest they encountered during it. Rear-Admiral R Tyrwhitt, the commander of the Royal Navy’s Harwich force, reported that on the whole the conduct of the German crews had been ‘satisfactory’, although he noted that the men ‘did not treat their officers with the respect and servility which one usually associated with the German Navy’ and that the men and their submarines were in general in a ‘dirty and uncared for state’.

Captain A P Addison, the commander of HMS Maidstone, one of the ships which coordinated the surrender, also submitted a report of his experiences on the water: he relayed two particular incidents where a truculent attitude to the surrender terms on the part of German sailors caused some problems.

In one case, while the German crew of a submarine were being loaded from their vessel into a motor launch, it was found that the white ensign of surrender that the vessel was to sail under had been removed. The crew were immediately returned to the U-Boat and searched – it turned out that one man had stowed the flag, along with a collection of pilfered fittings from the craft, in his belongings. Having jeopardised his comrades’ safe return to Germany with his shenanigans, he was not popular: Addison reported that his crew mates suggested to the British officer overseeing that he might like to keep the thief in his custody and ‘hang him’.

In another case it was an officer who caused trouble. During the surrender of the submarine U-90 the British officer taking over encountered difficulties with his German counterpart, named in Addison’s report has ‘Baron Frier Wangenheim (?)’. (Clearly, German nomenclature was not Addison’s strong point; I think the man referred to may be Freiherr Ernst von Wangenheim, although his commands do not match with Addison’s description according to this database).

Von Wagenheim apparently refused to take his boat up to Harwich harbour once the flag of surrender had been raised; however, he allowed his Engineering Officer to take command and did not prohibit his crew from surrendering. When accompanying the British officer around the U-Boat for his inspection, however, von Wagenheim gave a piece of his mind. ‘I hate you, and England’, he is reported to have said. While he admitted that Germany had lost the war, he promised to ‘fight against you in the next war’. Chillingly, von Wagenheim also made sure to let the British officer know that he had been second in command of the U-Boat which had sank HMS Cornwallis: ‘That was the happiest day in my life,’ he said. ‘My one regret is that only 30 men went down.’

However, von Wagenheim was an exception: the surrender was mostly an orderly affair, conducted between two sets of former adversaries who were no doubt glad that the horror of war was over.

The aftermath and commemoration

So, what happened to the submarines? Some were left around the estuary at Harwich to rust, leading to the port being sometimes nicknamed ‘U-Boat Alley’. However, from before the surrender the government had designs on the propaganda use of the vessels. On 19 November 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George explained his desire that captured submarines, ‘should be distributed and shown in the Thames, the Mersey, the Tees, the Tyne and the Clyde’. The submarines, he said, were ‘the outward and visible sign of victory’ which should be seen by the public, as they were, the Admiralty arranging for their display.[ref] Conclusions of Cabinet meeting held 19 November 1918. Catalogue reference: CAB 23/8/25[/ref]

There has been much discussion in recent months around the ultimate futility of the allies attempts to militarily neutralise and humiliate Germany, giving rise as it did to the feelings of bitterness and defeat which were exploited by the Nazis in their rise to power.

Image of surrendered submarines at Harwich from an article in the Illustrated London News, 30 November 1918. Catalogue reference: ZPR 34/153

However, the U-Boat surrender is something that has remained mostly forgotten in the 100 years since it took place. The Harwich Haven Surrender and Sanctuary project, a HLF backed group with whom The National Archives is partnered, is seeking to change this: they are commemorating this unusual and momentous event in a number of ways, including a beautiful wicker U-Boat on the beach at Harwich.

As usual a very interesting post.

However (to split hairs) I am not sure that the U-boat Surrender ‘has remained mostly forgotten in the 100 years since it took place’.

Although the fate of the vessels is not as well known as their surface counterparts at Scapa Flow, there have been periodic articles in the British national press and online about the post- surtender U-boat wrecks on (remote) mudflats on the River Medway.

I recall that Historic England were mapping the location of more that forty that sank at various places along the south and east coasts, usually after having stripped out and broken loose under tow.

Hi Richard,

Thanks for your comment, glad you enjoyed the blog. I take your point, there have definitely been some commemoration and heritage activities around the surrender, but it certainly isn’t as prominent in our collective memory of the First World War as other things are, including as you say the surface fleet’s surrender.

Thanks

Chris

Hi Chris.

Thank you for your reply. We agree about the submarine surrender and its place in collective memory – there are those who believe the U-boat threat was something specific to WW2.

My comments were designed to add information to your post by pointing out the work of other organisations on the surrendered German boats.

On a (perhaps) related point I believe a number of the engines of the scrapped U-boats found their way into British service – as electrical generators in power plants.

Once again thanks you for the post and your reply.

Hi Chris,

I came to this sight by accident searching for what happened to the German WW1 Submarines after the surrender. An interesting read, although I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.

I’ve hit a brick wall trying to find my Great-uncle’s Royal Navy service record.

I have a newspaper cutting stating his career and part of it says he “served in the engine room of a minesweeper in the North Sea, and after the war was in the escort to a number of German U-boats being taken to Palermo, Sicily”.

Do you know of any U-boats escorted to Palermo, Sicily, and which ships would have been the escorts?

Best wishes,

Richard

A question please . What was a Cruiser Submarine?