This year marks the 300th anniversary of the most pivotal year in the life of one of Scotland’s foremost historical figures, namely the outlaw and cattle rustler Rob Roy MacGregor; in continuation of the Early Modern Team’s Jacobite related blogs, I will examine records connected to it.

1716 would prove to be a momentous year for Robert MacGregor, having been outlawed on 30 June, and hunted by royal troops for kidnapping and ransoming; he was even in his own lifetime honored in chapter and verse.

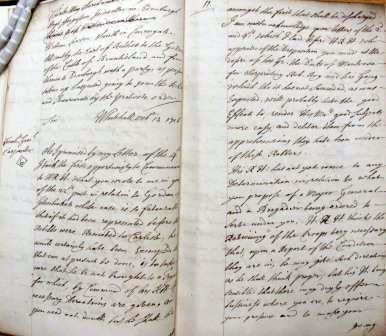

Forfeited Estates Commission, Robert Campbell called ‘Rob Roy’ (attainted for treason 13 November 1715), outlawed 30 June 1716, line indicating his entry (catalogue reference: FEC 1/672)

Robert Campbell (alias MacGregor), his popular moniker ‘Rob Roy’ coming from the Gaelic for ‘Red Robert’ (owing to his red hair), was born at Glengyle in the Trossachs region of central Scotland in 1671. His father was Donald MacGregor, and his mother Margaret Campbell. At that time Clan MacGregor was ‘proscribed’; James VI (soon to be crowned James I of England) had issued an edict in 1603 to abolish the name and the wearing of their tartan.

Ironically the ‘Gregor’ clan would prove to be firm supporters of the Stuart dynasty, the teenage Rob Roy having fought with Claverhouse’s victorious army at Killiecrankie in 1689. His involvement in the ‘Fifteen’ rising was virtually confined to his home territory, as he launched raids into Lennox on behalf of the ‘Old Pretender’ (son of the exiled James II). He was only an observer at Sheriffmuir in November 1715 (he would gain a reputation for martial caution with his avoidance of major engagements). With the rebellion over and the MacGregors on the losing side, he shrewdly placed himself under the protection of Campbell of Fonab, a close aide of his mother’s kinsman the loyalist Duke of Argyll (Commander-in-Chief of the government forces in Scotland).

Interestingly, other branches of the powerful Presbyterian Clan Campbell (like those of the Glenlyon Breadalbane line) favoured the Jacobite cause against the House of Hanover during 1715-16. However, the 2nd Duke of Argyll, John Campbell (or ‘Red John of the Battles’), sympathetically negotiated an amnesty for MacGregor as a result of his attainment for treason (in 1715) and his indictment of outlawry in 1716.

From his youth, Rob Roy frequently journeyed to the markets of Glasgow and Crieff to sell prized (and stolen) black Highland cattle. During his days as a cattle-stealer he became a member of the ‘Watch’ (a protection racket) which was aimed at Lowland farmers, who were thus blackmailed into letting the clansmen ‘guard’ their livestock. Though he became a prosperous and respected cattle dealer, his head drover allegedly absconded with monies given to Rob Roy by the Duke of Montrose.

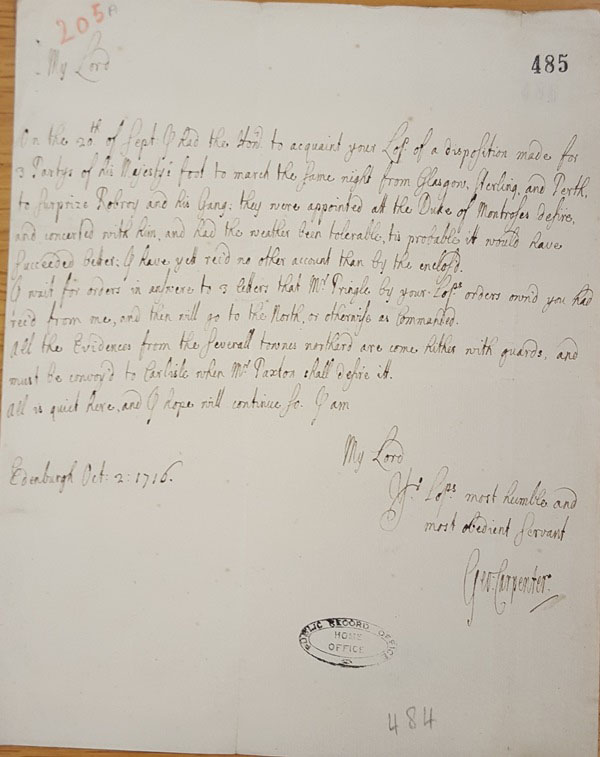

On the disposition of the Duke of Montrose in the capture of Rob Roy and his gang of robbers, 1716 Oct 13 (catalogue reference: SP 55/6/6)

The Duke unwisely mounted a ‘police action’ campaign against Rob Roy which lasted for almost a decade and helped forge the reputation of Roy as a Scots Robin Hood, an image which history has bestowed upon him ever since. Having been declared an outlaw, from this point onwards Rob Roy became a thorn in the side of the Duke of Montrose (an interim Secretary of State for Scotland) and the forces of the law that were sent to pursue him.

Escaping any harsh punishment, Roy was more or less left free to continue his personal feud with Montrose from whom he continued to steal livestock, and to humiliate those who served him. Roaming the hills of Loch Lomond, Roy abducted the Duke’s factor (land agent) John Graham of Killearn, who had been implicated in the burning of MacGregor’s house at Craigroyston, and whom he now held captive on an island in Loch Katrine.

General Carpenter on an attempt to capture Rob Roy: ‘had the weather been tolerable, tis probable it would have succeeded better’, 2 October 1716 (catalogue reference: SP 54/12/205A)

While many believed he had fled abroad (see SP 55/8/54), Rob Roy and the whole of the MacGregor clan were specifically excluded from the benefits of the Indemnity Act of July 1717, which had the effect of pardoning all others who took part in the rebellion of 1715 (see C 65). Most of the surviving Jacobite prisoners were freed and were permitted to settle either at home or overseas by the Act. However it did not undo the effect of the attainders and confiscated estates worth £30,000 a year in Scotland (and £48,000 in England); nor were the dispossessed restored to their lands.

Although taking part in the failed Jacobite incursion of 1719, Roy managed to withdraw from that ill-starred enterprise without serious repercussions. He was eventually brought to justice in 1722 and imprisoned for five years (after converting to the ‘old’ Catholic faith in 1720).

It was during his captivity that the legend of Rob Roy started to outstrip reality. Author Daniel Defoe (of Robinson Crusoe fame) wrote a highly coloured account of his life in the ‘Highland Rogue’ (1723). As a result, Robert MacGregor became a celebrity in his own lifetime. The popularity of Defoe’s account (even in Court circles) may have led King George I to issue a pardon and free Rob Roy at the end of his reign in 1727, just when he was due to be transported to the American ‘Plantations’. He would die peacefully in his bed in 1734.

Ultimately Rob Roy’s fame lived on, and was assured when Sir Walter Scott wrote a best selling novel in 1817 based on his life, entitled simply, ‘Rob Roy’. Meanwhile Wordsworth’s poem ‘Rob Roy’s Grave’ also memorialised him in verse during the initial Regency craze for ‘all things Scottish’. Aside from the highly romanticised 1995 film version, elsewhere in popular culture there has been at least two other screen adaptions of Rob Roy’s story: the 1922 silent classic (starring David Hawthorne), and the seldom shown 1953 Disney production of ‘Rob Roy Highland Rogue’ (with Richard Todd in the lead role and James Robertson Justice as Argyll).

Thanks Ralph! A Great synopsis of Rob Roy’s story and of the records held at the National Archives about him.

it should say Glengyle, Crieff and Killikrankie and not as spelt

I should have checked before posting, it is Killicrankie.

Thanks for your comments, David. I have corrected those words.

Best,

Nell