Yesterday marked the official retirement of John Sentamu, the 97th archbishop of York. The UK’s first black archbishop, since 2005 Dr Sentamu has ministered to the Northern Province of the English Church and has been prominent in its global evangelical mission. His successor, Dr Stephen Cottrell, has expressed his wish of ‘being a voice for the North’[ref]‘Stephen Cottrell will be new Archbishop of York’, BBC News, 17 December 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-50821262.[/ref].

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded The Northern Way project – a partnership between the University of York, The National Archives and York Minster – is reflecting on the relationship between previous archbishops of York, their province and royal government. Here, Kirstin Barnard, PhD student at York, examines a controversy that arose during the episcopate of Alexander Neville (1374-1388), the 45th archbishop.

In a 1381 petition to King Richard II, the ‘greater burgesses’ of Beverley in the East Riding of Yorkshire complained that ‘rioters and trouble-makers have taken control of the town government of Beverley’. They had tried to break a political monopoly and private profiteering by removing the 12 ‘keepers’ – elected annually at the feast of St Mark (25 April) – and installing a new oligarchy of two elected chamberlains and an alderman. Burgesses such as Thomas Beverley stated that ‘they dare not approach the town for fear of death’ and asked the king not to execute large financial bonds, exacted from them by threats of violence.

In response, on 16 April 1382, Richard ordered the sheriff of Yorkshire to arrest Richard Boston and the two former chamberlains of Beverley, Henry Newark and Thomas White. The sheriff returned, however, that these men could not be found. Another writ of the same date ordered Archbishop Alexander Neville to arrest the same men in his capacity as lord of the town.

In June 1382 Neville visited Beverley and took pledges for good behaviour from the townsmen and in October royal pardons were brought for 1,100 marks (c. £700). This new organisation, though, survived at least until 1386. Many burgesses subsequently fled to London where they petitioned the king. Many of the petitions survive in The National Archives (TNA SC 8/225/11201-11242, 11247). This was not, however, the only political, jurisdictional conflict in which Neville was involved at this time in Beverley.

From March to May 1381, Archbishop Neville undertook a controversial visitation of Beverley Minster, the other main source of authority in the town. A visitation was the inspection of a religious institution – here a college of priests living together called canons – by church authorities to inspect all aspects of spiritual and temporal life and correct wrongdoing. Visitation records are not always prominent in the archbishops’ registers (the principal administrative record) and few survive in the royal government archive at The National Archives.

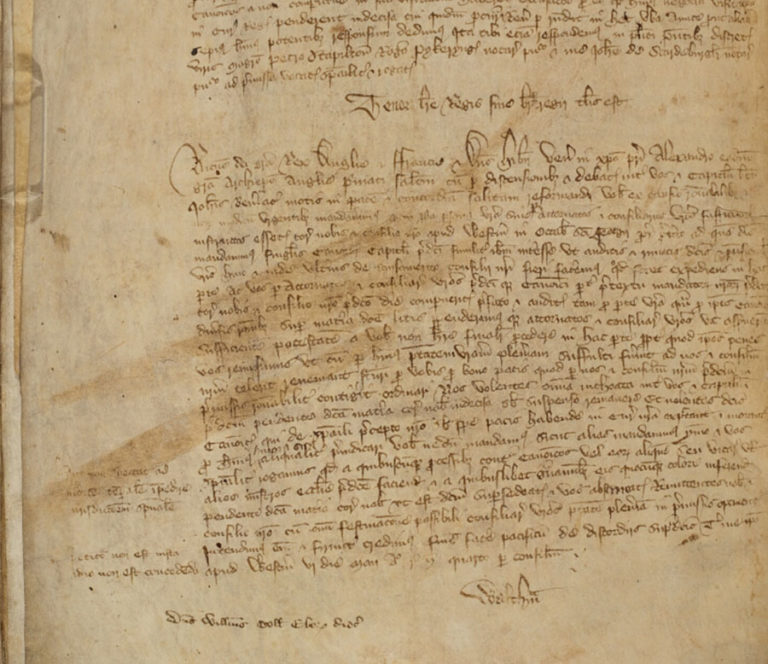

However, one of the registers from Neville’s archiepiscopate relates to his visitation of Beverley. This register, along with the other registers of the archbishops of York from 1225 to c.1650, kept at the Borthwick Institute for Archives, has been digitised: the images are freely available online.

Visitations could become contested. This was because they aimed not only to maintain spiritual standards, but were also a way to strengthen an archbishop’s authority or push for particular policies. This created tensions, especially for institutions that claimed liberties from (arch)bishops’ jurisdictions or were protective of their own rights, as with Beverley.

To understand the nature of this dispute, let’s examine the process in more detail. To begin a visitation to a religious institution, a forewarning was issued with a citation to appear at the correct time and place. A citation for Beverley Minster dated 2 March 1381 is recorded in Archbishop Neville’s register, calling all the canons and chapter of the Minster to appear in person before him on 27 March.

When Neville arrived in Beverley on 26 March, despite a public sermon that he would not interfere with the canons, vicars and other ministers, or hear any cases in his capacity as archbishop, he received a number of complaints from the chapter of the Minster (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, ff.77v-78r).

One letter claimed that as the archbishop was not a canon of the chapter, he had no place or voice within it. The second letter was an appeal by the chapter to Pope Urban VI stating that its privileges meant it was exempt from external visitation, except once by the archbishop of York (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, f.80r).

Traditionally, archbishops had rights to visitation when they had been newly installed into their see, but the appeal argued that Neville, attempting a personal visitation seven years after his appointment, was infringing its exemption.

This appeal refers to an important process of visitation: the inhibitions. These essentially suspended the jurisdiction of all authorities under the visiting (arch)bishop throughout the visitation, allowing him to pass sentences and corrections. Such inhibitions explain why visitations could cause ructions with communities jealous of their rights and level of independence.

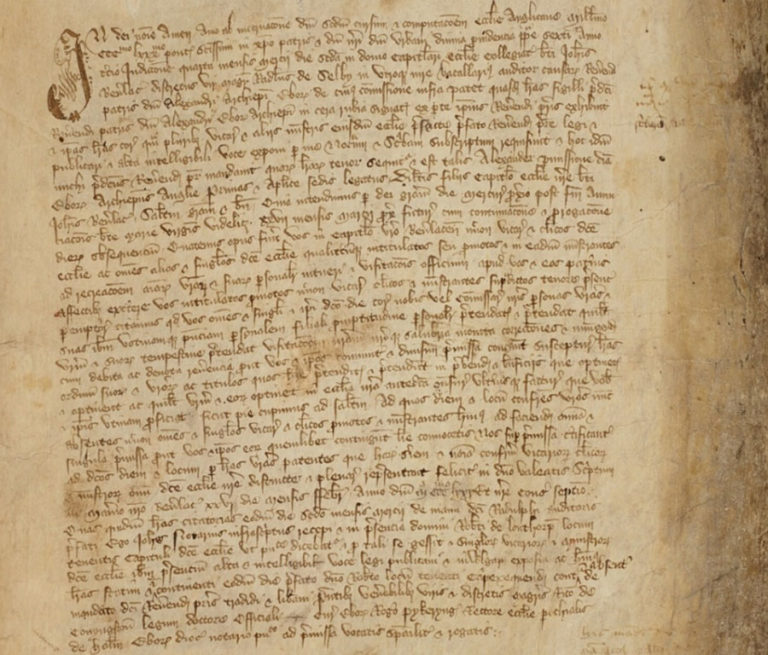

The register records Neville’s reply to these letters: he did not intend to over-step his jurisdiction, but did intend to exercise it (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, f.82v). The concern over authority within these records speaks to the complex jurisdictional boundaries that existed in Beverley. Whereas the archbishop’s overlordship in the town was recognised, this was more ambiguous in the Minster a royal foundation.

Archbishop Neville attempted to continue the visitation by entering the Chapter House on 26 March. Normally, after an introductory sermon, members of the community would present the documents relating to their ordination, appointments to office and foundation charters. The community would then be questioned individually about the state of their institution and their behaviour, which generated three similar, but separate, forms of document.

First, the detecta (or discoveries) recorded in writing the individual testimonies given at the visitation. Second were the comperta (or findings), summarised lists of the problems discovered. The comperta were issued to the members of the house who were summoned together again. From a collation of the comperta, a list of corrections, known as injunctions, was issued verbally.

This process was not fully realised at Beverley in 1381, however; the day before the visitation was scheduled to begin only the precentor, one clerk of barfel and one chantry priest turned up to present their relevant documents. On 29 March, the vicars came to the Chapter House and claimed they could not attend for fear of the canons, who were their superiors. The vicars then left, apparently in a ridiculous (derisorie) manner.

This negative description demonstrates that we cannot consider the texts within the registers (or indeed any record) as apolitical or objective. Instead, they both reflect and support the particular aims and perspective of the archbishop.

On 3 April, the vicars again claimed that they could not swear an oath to the archbishop, because the chapter had made them swear on the Gospels that they would not make an oath to anyone else. The visitation was adjourned until 5 April. A day later, the vicars had disappeared. They had left for London, leaving Beverley Minster without services, in an attempt to disgrace the archbishop. They were therefore excommunicated. Vicars from York and Neville’s own clerks were brought to continue services, and the visitation proceedings were further postponed (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, f.86r).

Usually, visitations were formally dissolved after the injunctions were given. After the visitation party left, these were sent as written documents and were sometimes copied into the (arch)bishops’ registers. These records are not present in Neville’s register for Beverley Minster because of the disruption that the dispute caused. That the conflict had reached new heights is evidenced by a writ from Richard II, presented to Neville on 21 April. This chastised him for his interference with the canons, reminding him that some of the chapter were the king’s clerks and that Beverley Minster was a royal foundation (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, ff.86r-v). The writ commanded Neville to appear at Westminster to settle the dispute.

Despite being posthumously named as his loyal servant by Richard in September 1392, there were tensions in their relationship at the start of the 1380s. Neville certainly continued his attempts to undertake the 1381 visitation. Copied into his register are certificates and letters relating to the excommunication of the vicars and some of the canons (BIA/YDA/2/Abp Reg 13, ff.85v, 86v, 88r).

By 1385, however, Neville had aligned himself politically with the king and was in his inner circle. This alliance later resulted in his retreat northwards from the increasingly powerful magnates – the Lords Appellant – who were hostile to the king and charged Neville with treason in February 1388. Neville was not executed but the charge marked the end of his political career. Unable to take up his position as bishop of St Andrews in Scotland, to which he was translated in April 1388, Neville was forced into exile, where he died in May 1392.

At Beverley Minster, it was the king’s involvement which finally ended the 1381 visitation (though not the dispute). The last document copied into the register relating to Beverley was a mandate from Richard II of 6 May, commanding Neville not to proceed and to return his council from Beverley immediately.

Marginal comments in the register surrounding this letter indicate how it was received. One states: ‘it ought not pertain to the temporal authority to obstruct the spiritual’ (‘Nota non spectat ad jurisdictionem temporalem inpedire jurisdictionem spiritualem’). At the end of the letter it was also noted that the canons’ petition was not just, and the matter was not to be conceded. This comment begs many questions about how the matter was dealt with thereafter.

The end of the visitation almost coincided with the outbreak of what, further south, became the Peasants’ Revolt in late-May 1381. The political unrest at Beverley, with the election of the town’s keepers on 25 April, foreshadowed to some extent the levelling violence of the Revolt (currently being investigated by the People of 1381 project). It is possible that the instigators of Beverley’s political upheaval – Boston, Newark, White et al – used the tensions between the Minster and the archbishop of York to play them off against each other.

The study of visitation documents and those documenting the interaction between Church and State can help us develop a better insight into archbishops’ relationships with the religious institutions and political communities within their province. We trust that Archbishop Stephen will find no such conflict and we wish Dr Sentamu a very happy retirement.