Nelson Mandela was born at Mvezo, a village near Umtata, Transkei (now Eastern Cape) on 18 July 1918 into the royal lineage of the Thembu people. In this remote and rural part of South Africa, Mandela’s early life was in accordance with traditional African custom.

Mandela was educated at the missionary Clarkebury Boarding Institute and Healdtown College, not very far from his birthplace. Subsequently, he studied at the newly established University of Fort Hare in the Eastern Cape. The University offered academic education for Africans and became a key institution in the formation of an African political elite. He moved to Johannesburg in 1941 and worked for the liberal law firm Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelman before attending the University of the Witwatersrand. There he met key anti-segregationist thinkers and activists, including Walter Sisulu, Joe Slovo and Ruth First. He was instrumental in the formation of the African National Congress Youth League in 1943.

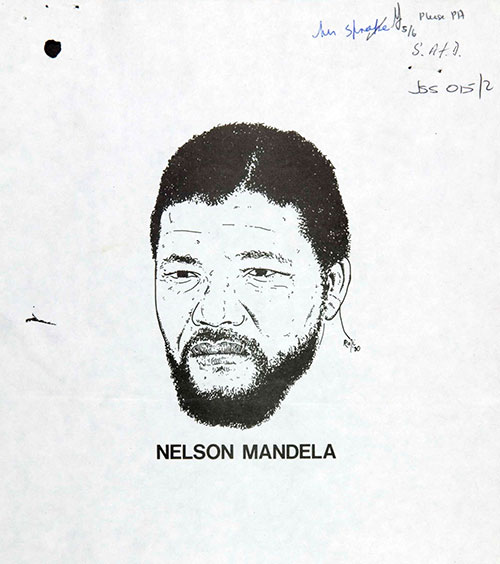

Unattributed ink sketch of Nelson Mandela, circa 1980. FCO 105/442 Civil disturbance in South Africa: political prisoners, including James Mange and Nelson Mandela, 1980.

At that time, South Africa was a segregated country. Mandela was a young, politically conscious man in a country in which he could not vote and was subject to the humiliations of pass laws and colour bars. 1948 saw things changes for the worse, as the Afrikaner National Party under Daniel F Malan won the general election. In a position of power, which would not be overthrown until the 1990s, the Nationalists oversaw the transition from segregation to apartheid, instigating a programme of repressive legislation.

The 1950s were a busy time for Mandela. He joined the African National Congress (ANC) National Executive and in 1952 opened the law firm of Mandela and Tambo, using his legal knowledge to defend the oppressed. In that year, he was arrested under the Suppression of Communism Act and served a short sentence. Further arrests followed in the course of the 1950s.

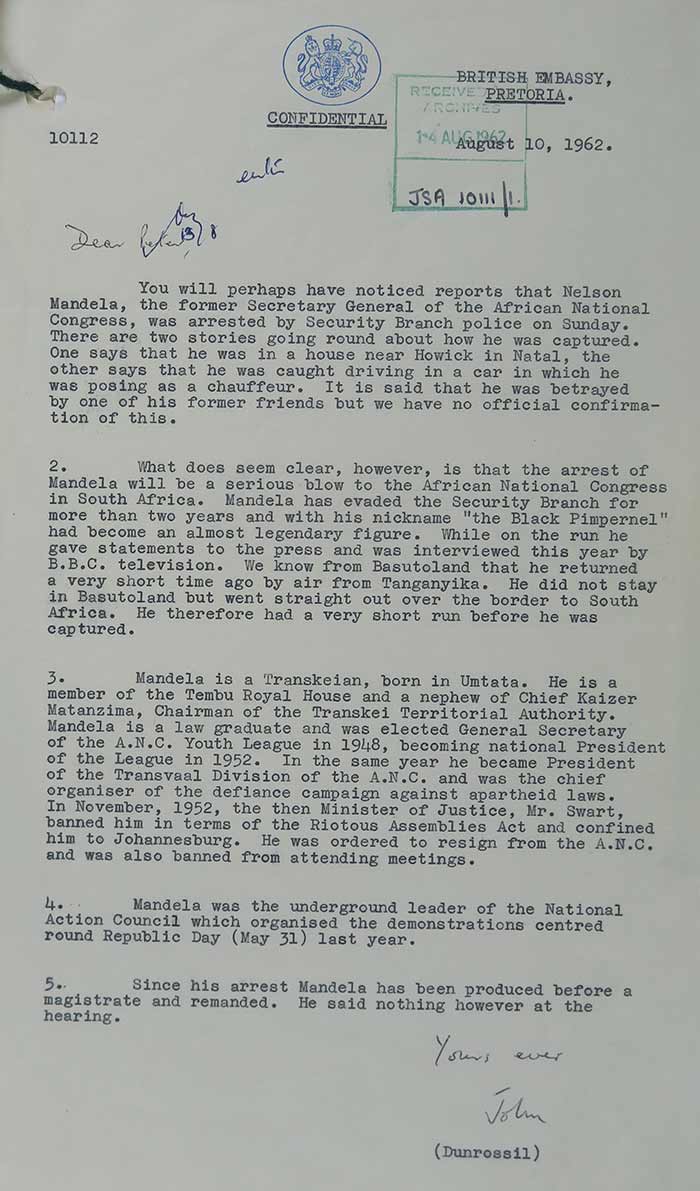

The British Ambassador to South Africa, Lord Dunrossil, informs the Foreign Office of the arrest of Nelson Mandela in August 1962. FO 371/161901 Trial of Nelson Mandela, 1962.

In the increasingly authoritarian and oppressive South Africa of the 1950s, and with the massacre by the police of anti-pass demonstrators at Sharpeville in 1960, Mandela’s stance hardened to an acceptance of the need for armed struggle. In 1961, he co-founded Umkontho we Sizwe (MK – Spear of the Nation), which began a campaign of sabotage aimed at infrastructure. During a year of travelling, organising opposition and evading the authorities, he became known in the press as the ‘black pimpernel’.

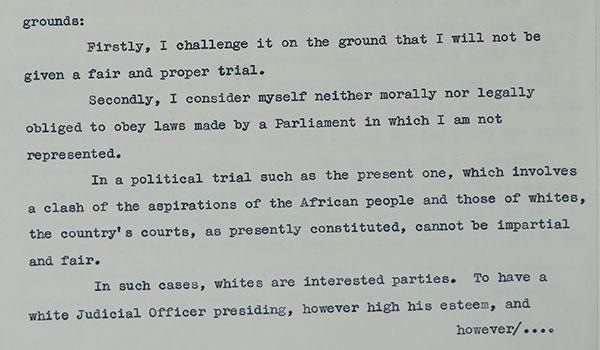

A transcript of Mandela’s address at his trial in 1962 in which he denied the authority of the court. FO 371/161901 Trial of Nelson Mandela, 1962.

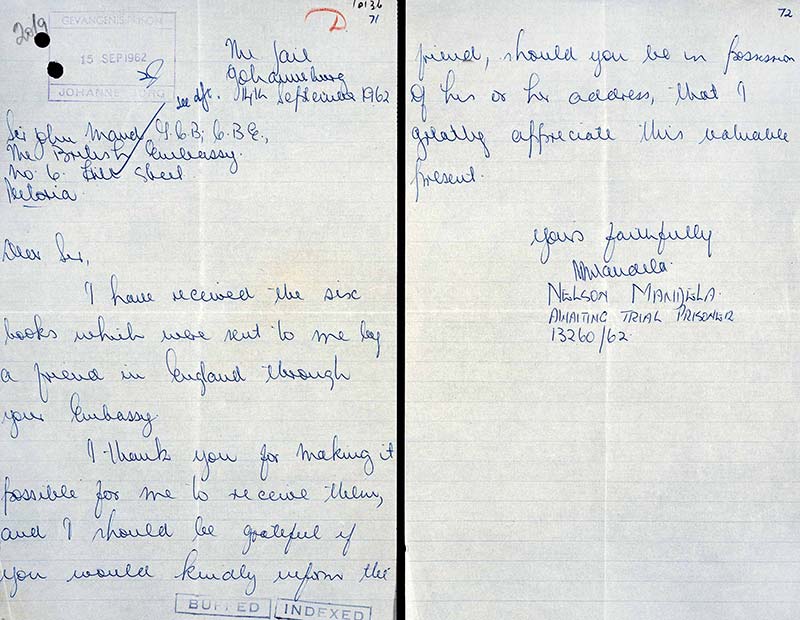

Eventually, though, he was arrested, reportedly dressed as a chauffeur, near Howick, Natal in August 1962. He was charged with inciting strikes and leaving the country without permission. At the opening of the trial, Mandela made a speech in which he denied the authority of the court in the apartheid state to decide on his case. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. A file at The National Archives shows how David Astor, editor of The Observer and a firm opponent of apartheid, arranged for books to be sent to Mandela in prison. It includes Mandela’s handwritten note of thanks.

Mandela’s note of thanks to Sir John Maude at the British Embassy in Pretoria for arranging a gift of books from David Astor to be sent to him in Johannesburg Prison. DO 119/1478 Nelson Mandela: arrest and trial, 1962

Things changed in July 1963, when the police raided the farm Liliesleaf in Rivonia, north of Johannesburg, where several anti-apartheid activists were known to be living. They found documentation with implicated Mandela in MK’s activities. Mandela, along with several others, was now charged with more serious offences, including attempting to violently overthrow the government – which effectively amounted to treason. These were serious charges which could potentially have incurred the death penalty.

In 1964, Mandela, was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. He would spend nearly 28 years in prison, 18 of them in the high-security prison on Robben Island, some seven miles out in the cold Atlantic to the west of Cape Town. The small island was a bleak place, which had been used in the past by the colonial authorities as a leper colony and animal quarantine station. Here, prisoners laboured in the island’s limestone quarry and the health of many suffered in its dusty atmosphere and the reflected glare of its white surfaces. Time was also spent in conversation with other imprisoned ANC members and anti-apartheid campaigners, and in study. Suffering from tuberculosis and other health problems, Mandela was transferred to better conditions at Pollsmoor Prison near Cape Town in 1982.

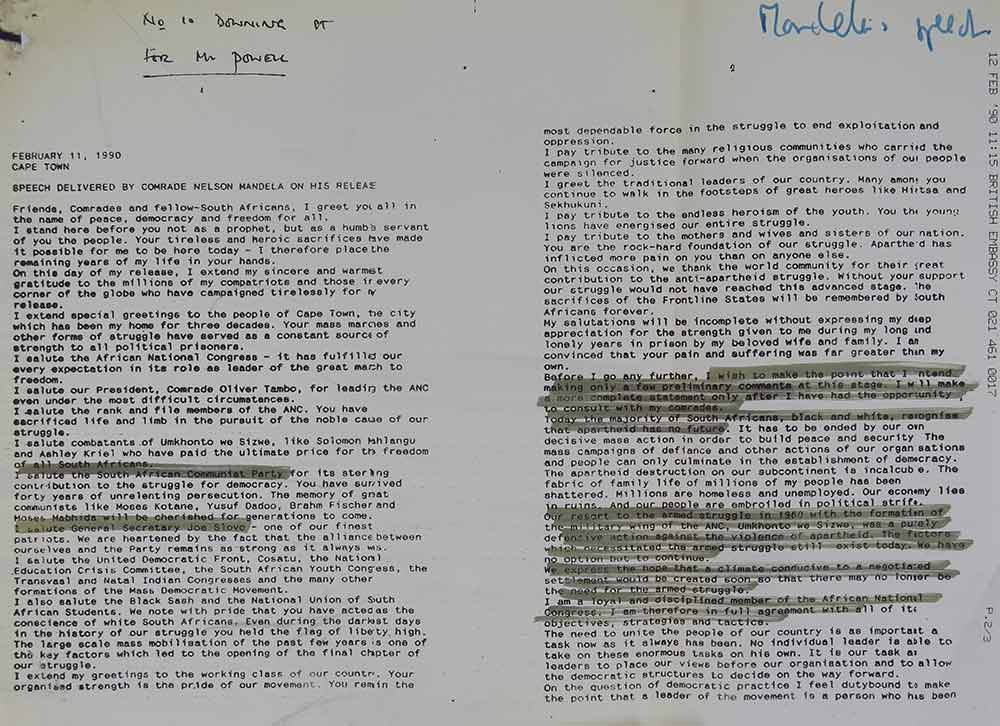

Outside, the struggle against apartheid continued and eventually led to negotiations with F W de Klerk’s Nationalist Government. Mandela was unconditionally released from prison on 11 February 1990. On the same day, he addressed a large audience outside Cape Town City Hall, reaffirming the ANC’s commitment to ending apartheid and to a democratic South Africa.

Excerpt from Mandela’s speech outside the Cape Town City Hall on his release from prison in February 1990. PREM 19/3171 SOUTH AFRICA. UK/South African relations: internal situation; release of Nelson Mandela; part 21, 1989-1990.

Mandela went on to lead the ANC to victory in the general election of April 1994. He served as President of the Republic of South Africa until 1999, overseeing the work of the Government of National Unity, the adoption of a fully democratic constitution and fostering national reconciliation through the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He enjoyed a politically active retirement, before withdrawing from an overtly public role in 2004. He died in Johannesburg in on 5 December 2013, at the age of 95.

There are number of files that are with-held about Mandela including one from the Prime Minister’s Office which is retained on grounds of ‘prejudice to HM Government’s relations. It is well-known that Margaret Thatcher didn’t like him and she and her government were against sanctions against Apartheid South Africa, despite the rest of the Commonwealth pressing for sanctions.

Good Morning Nelson Mandela you are my father in memorial motivation my life.thank a lot