One hundred years ago, on 28 February 1922, Edmund Allenby, the British High-Commissioner in Egypt, wrote to Sultan Fuad. ‘The British Protectorate over Egypt is terminated,’ he stated, ‘and Egypt is declared to be an independent sovereign State’. Forty years after first occupying Egypt, the British were finally leaving the banks of the Nile. Or were they?

The 1919 Revolution

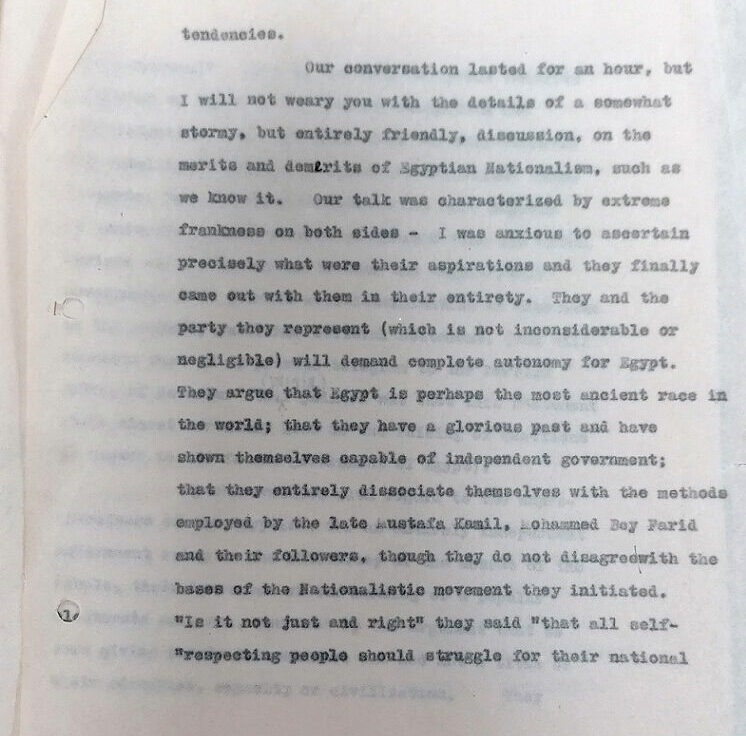

On 13 November 1918, three members of the People’s Party met with the British High Commissioner in Cairo, Sir Reginald Wingate. Saad Zaghloul, Abd al-Aziz Fahmi, and Ali Shaarawi told him they wanted to take a delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, where they would argue for the independence of Egypt.

Wingate told the Foreign Office that Zaghloul had been chosen by the Legislative Assembly to take the Egyptian question to Paris and that his movement, known as ‘the Egyptian Delegation’ (al wafd al-misri, or simply the Wafd) was quite popular. He advised the British government to agree to the request or at least meet with them in London. The Foreign Office declined.

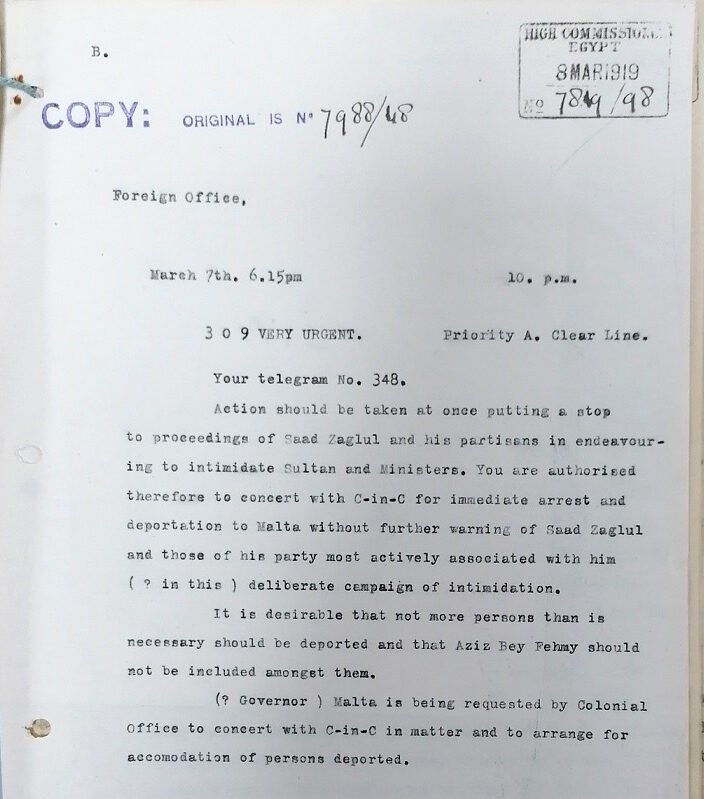

On 8 March 1919, the Wafd leaders were arrested and deported to Malta on the following day (FO 141/773/10).

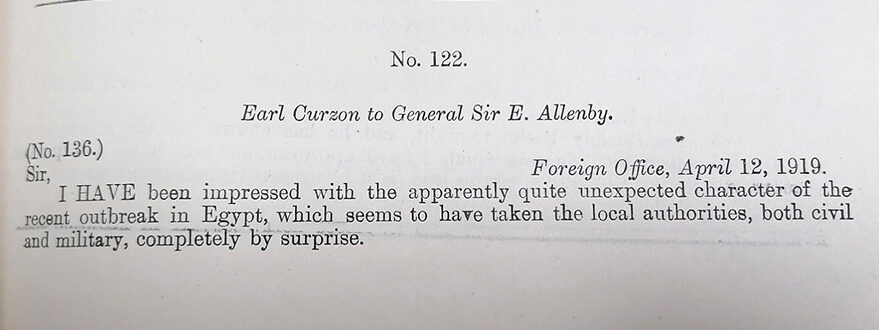

This led to a massive popular uprising, which took the British authorities by surprise. British buildings were targeted, railways were damaged, and the Wafd’s popularity grew exponentially (FO 848/1).

In April 1919, Edmund Allenby, who had replaced Wingate as High Commissioner, claimed that the nationalist movement had taken a religious and fanatical turn. He was wrong. Muslims and Christian Copts were marching together, chanting the same chants demanding the independence of Egypt, and waving banners displaying both the crescent and the cross. For the first time, women, led by Safia Zaghloul and Hoda Shaarawi, played an active role in national politics by marching en masse on 16 March. The demonstrations were brutally crushed by the British Army, only comforting the Egyptians in their determination to obtain independence.

The reaction of the Egyptian people was obviously more nuanced and complicated, but the overpowering sense of national unity that prevailed forced Britain to reconsider its position. On 7 April 1919, Zaghloul and his fellow Wafd members were released. On the 11th, they headed to Paris.

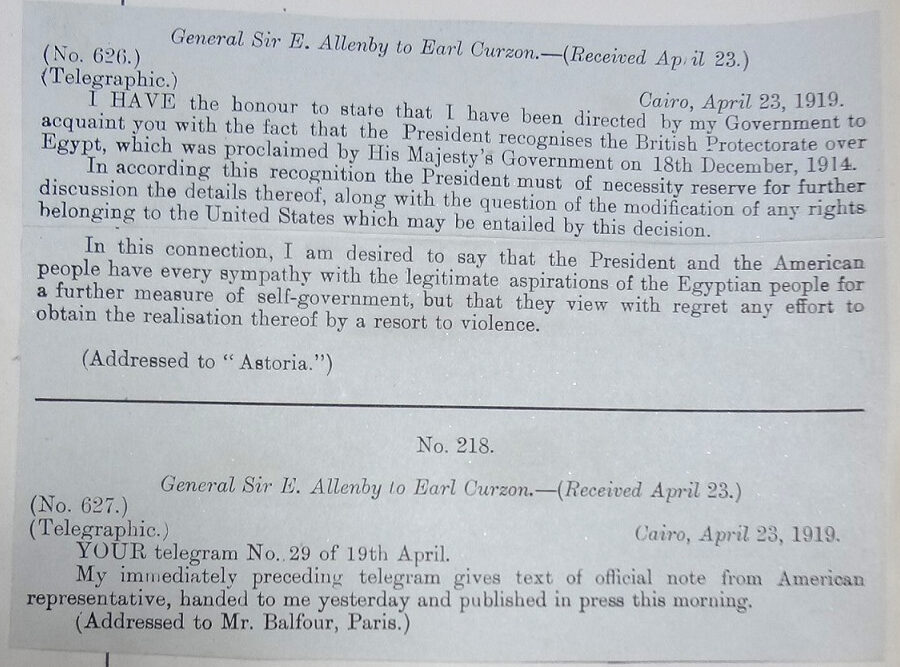

The Peace Conference turned out to be nothing but a series of disappointments. On the very day the Egyptian delegation arrived in Paris, the United States officially recognised the British protectorate over Egypt (FO 371/7731).

Pressured by Britain, most delegations refused to meet with the Egyptians to discuss independence. The fatal blow came on 28 June 1919. Article 147 of the Treaty of Versailles stated:

‘Germany declares that she recognises the Protectorate proclaimed over Egypt by Great Britain on December 18, 1914, and that she renounces the regime of the Capitulations in Egypt. This renunciation shall take effect as from August 4, 1914’

Catalogue ref: FO 93/36/76

As the treaty was signed by all the Allies, this was an almost universal recognition of the British protectorate. The 1919 Revolution seemed to have failed.

The Milner Mission

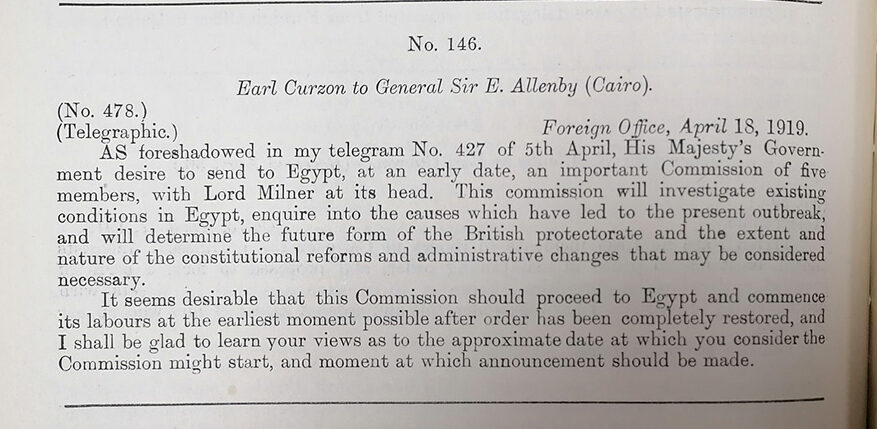

In May 1919, Lord Milner, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, was instructed to lead a special mission

‘to investigate existing conditions in Egypt, enquire into the causes which have led to the present outbreak and (…) determine the future form of the British protectorate and the extent and nature of the constitutional reforms and administrative changes which may be considered necessary’

Catalogue ref: FO 848/1

When the members of the mission arrived in Egypt in December, it soon became apparent that ‘the Egyptian Nation in common accord [had] decided to boycott the Milner Mission’ (FO 848/13). The boycott was extremely successful. When the mission left Egypt in March 1920, its failure was blatant and it was clear Egypt would never agree to anything less than total independence.

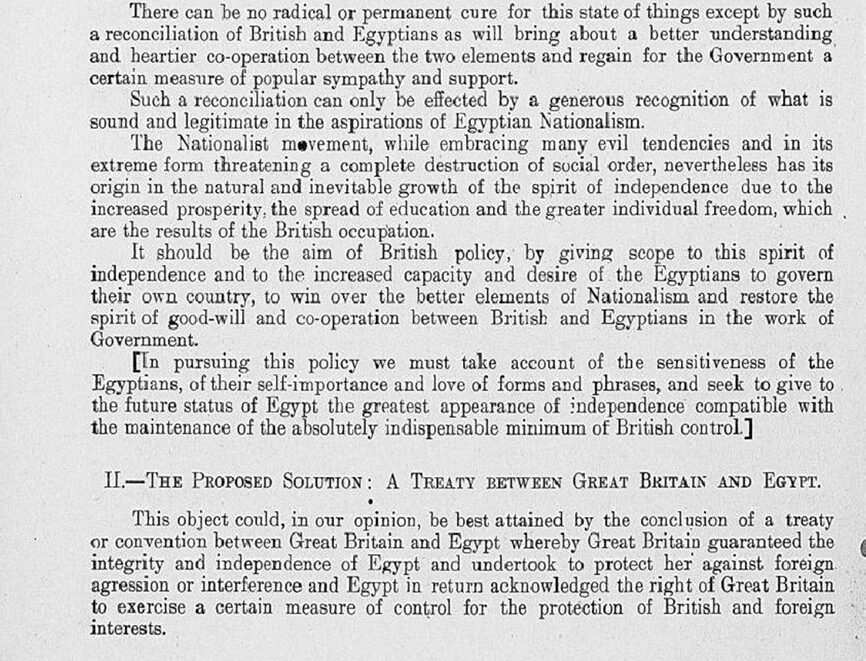

A preliminary report was handed to the Foreign Secretary in May 1920. According to the Milner Report, the time of direct British rule had come to an end, and autonomy within the frame of a protectorate wouldn’t work. The nationalist movement was growing, the report stated, and what was really needed was a compromise between Egypt’s national aspirations and Britain’s interests. Such a compromise, the report claimed, could only be reached through ‘a generous recognition of what is sound and legitimate in the aspirations of Egyptian nationalism’. A bilateral treaty would have to be signed (CAB 24/112/60).

The conclusion of the Milner report was a victory for the Wafd. It was almost (almost!) recognising that British control over Egypt could no longer be implemented without the cooperation of the Egyptians themselves. A treaty would have to be negotiated, and Britain and Egypt would be on an equal footing.

After 38 years of occupation, the British were finally taking Egyptian national aspirations seriously. Or were they?

Negotiating independence

Mid-July 1920, Milner made a first proposal, very much in favour of Britain. Egypt would be committing to not signing any treaty with any foreign state without British approval, to the presence of a substantial British force in the country, and to British legal and financial advisors in government.

Unsurprisingly, the Wafd rejected the terms and submitted a counter-proposal. Britain would recognise Egypt’s independence as a constitutional monarchy, it would remain responsible for the protection of foreigners and foreign interests in the country, and could use the eastern bank of the Suez Canal as a base to safeguard imperial communications. The Sudan, hitherto under an Anglo-Egyptian condominium, would be dealt with by a separate treaty.

Unsurprisingly, Britain rejected the proposal. The negotiations reached a deadlock.

In August 1920, Milner submitted yet another proposal, which seemed to be a compromise, but according to which Britain would retain substantial legal and financial powers. The Wafd decided not to do anything without consulting the Egyptian people (FO 848/1).

The Egyptian government eventually rejected the proposal, and Saad Zaghloul and his fellow negotiators headed back to Cairo, where they received a hero’s welcome.

A unilateral declaration of independence

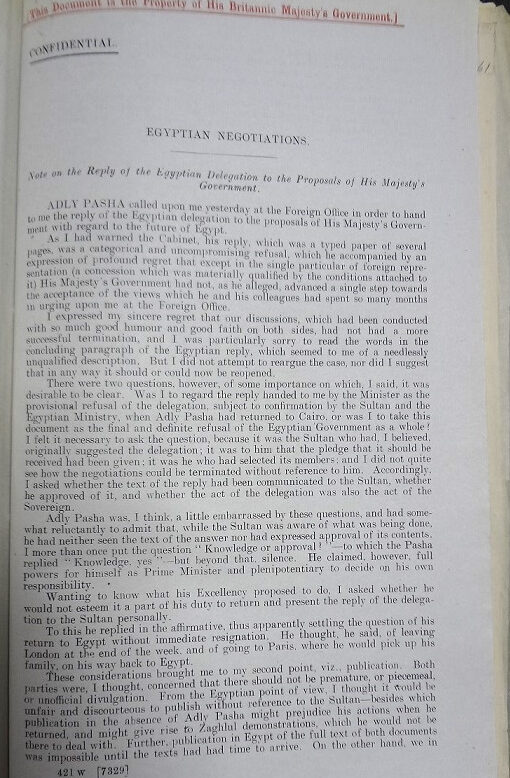

In July 1921, an official delegation, sent by Sultan Fuad to negotiate a treaty, travelled to London. It was headed by the President of the Council of ministers, Adly Yeshen Pasha, and was composed of ministers and former ministers. Zaghloul was not among them.

Around the same time, the Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, declared that the Egyptian problem was ‘the worst of all of those we have had before us’. Negotiations were carried out at a sluggish pace and, in August 1921, the British submitted a proposal no Egyptian government could ever sign (FO 141/443/3).

The Egyptians were basically given the choice between accepting the protectorate would be maintained, or signing a proposal which in theory recognised Egypt as an independent sovereign state but in reality reasserted the very principle of British occupation. The same happened in November. The negotiations broke down, and the delegation headed back to Cairo.

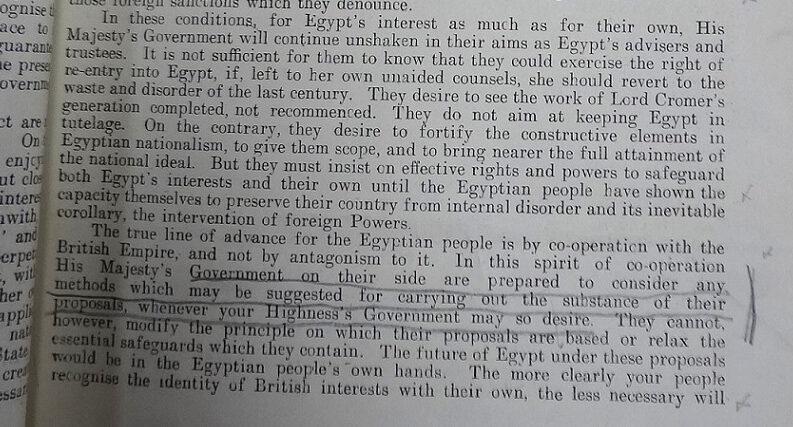

On 3 December 1921, Allenby wrote to Sultan Fuad, claiming that Britain was in favour of Egypt ‘enjoying the national prerogatives and international position of a sovereign state, but closely wedded to the British Empire by a treaty of guarantee of common aims and interests’. If Egypt, he wrote, declined the British proposal to replace the protectorate by ‘a perpetual treaty and bond of peace, amity and alliance’, Britain would have to reconsider its position (FO 141/443/3).

Zaghloul and his closest associates were arrested on 23 December 1921, and deported. Just like in 1919, this caused demonstrations and strikes, as well as violent skirmishes with the police.

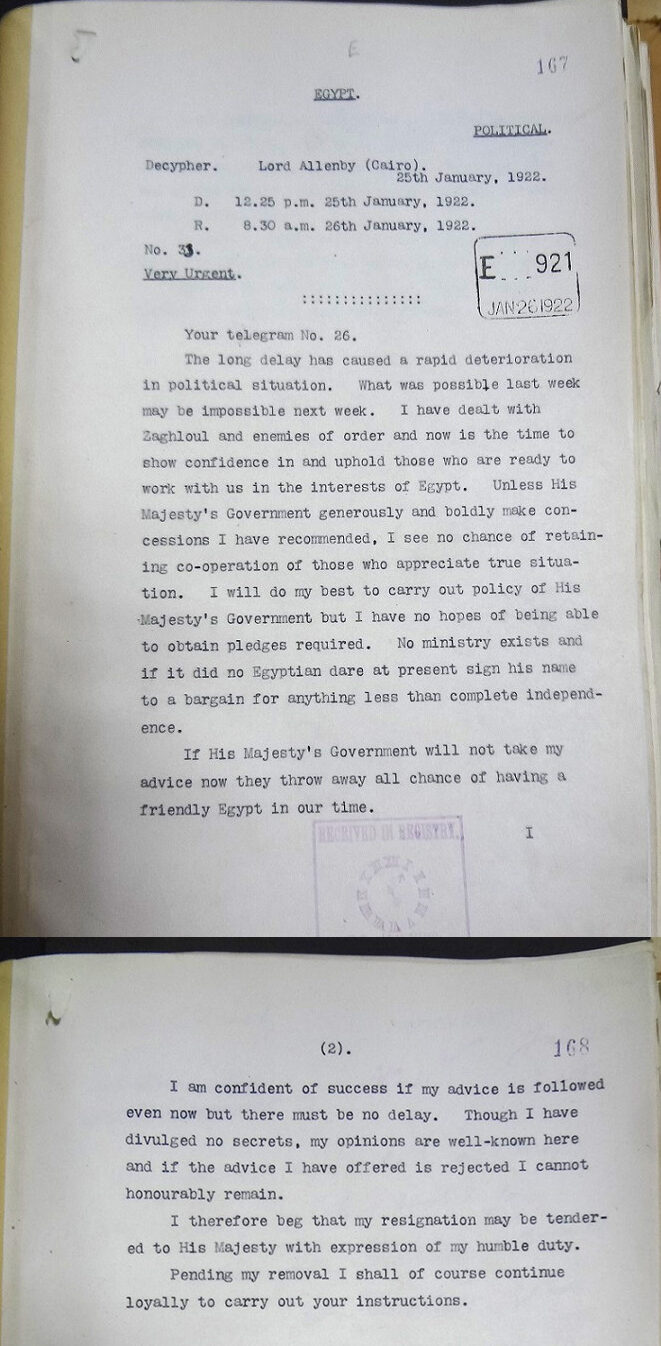

In January 1922, the Egyptian government rejected the British proposal. In February, Allenby left Cairo for London and threatened to resign if the protectorate wasn’t abolished.

On 4 February, Safia Zaghloul addressed the Egyptian people: ‘be patient, for you are about to reach the end of the road and, with the help of God, will be victorious’ (FO 141/511/6).

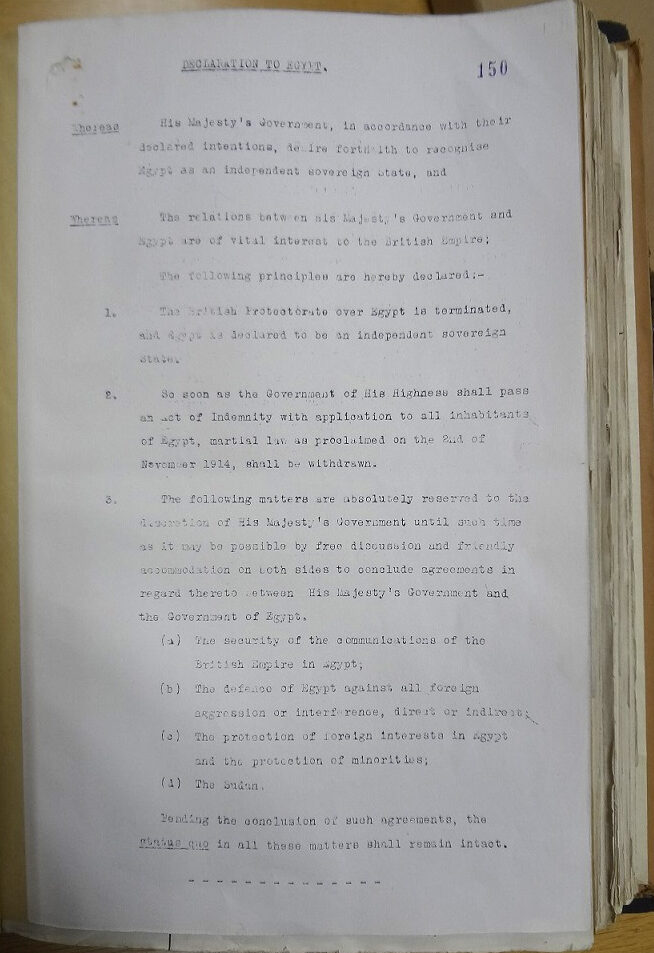

On 28 February 1922, Allenby wrote to the Sultan again:

‘The British protectorate over Egypt is terminated, and Egypt is declared to be an independent sovereign State’

Catalogue ref: FO 371/7732

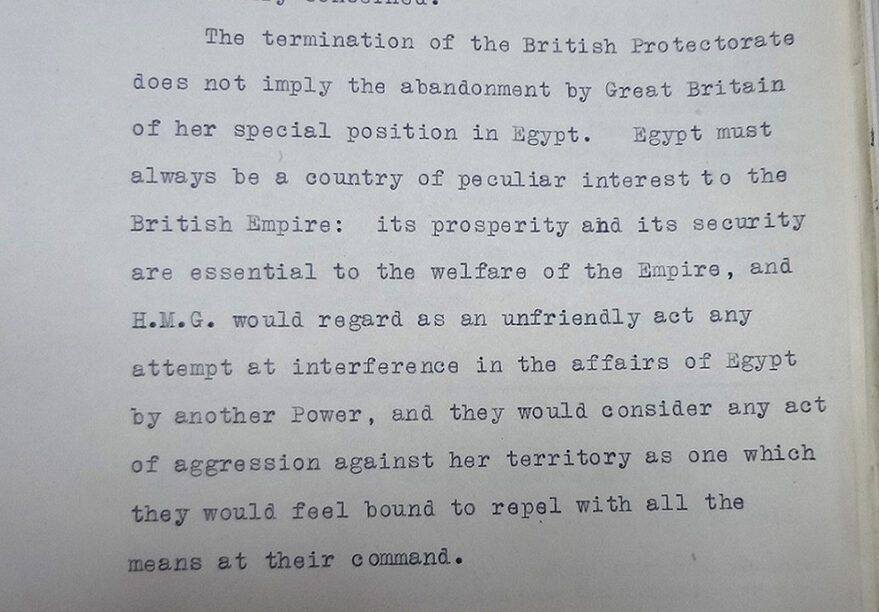

Through a unilateral declaration, Britain was granting Egypt independence. Or some form of it. Britain retained four major privileges: the safeguard of imperial communications; the defence of Egypt against foreign aggression; the protection of foreign interests; and the question of the Sudan. Egypt was clearly to remain part of Britain’s sphere of influence (FO 371/7731).

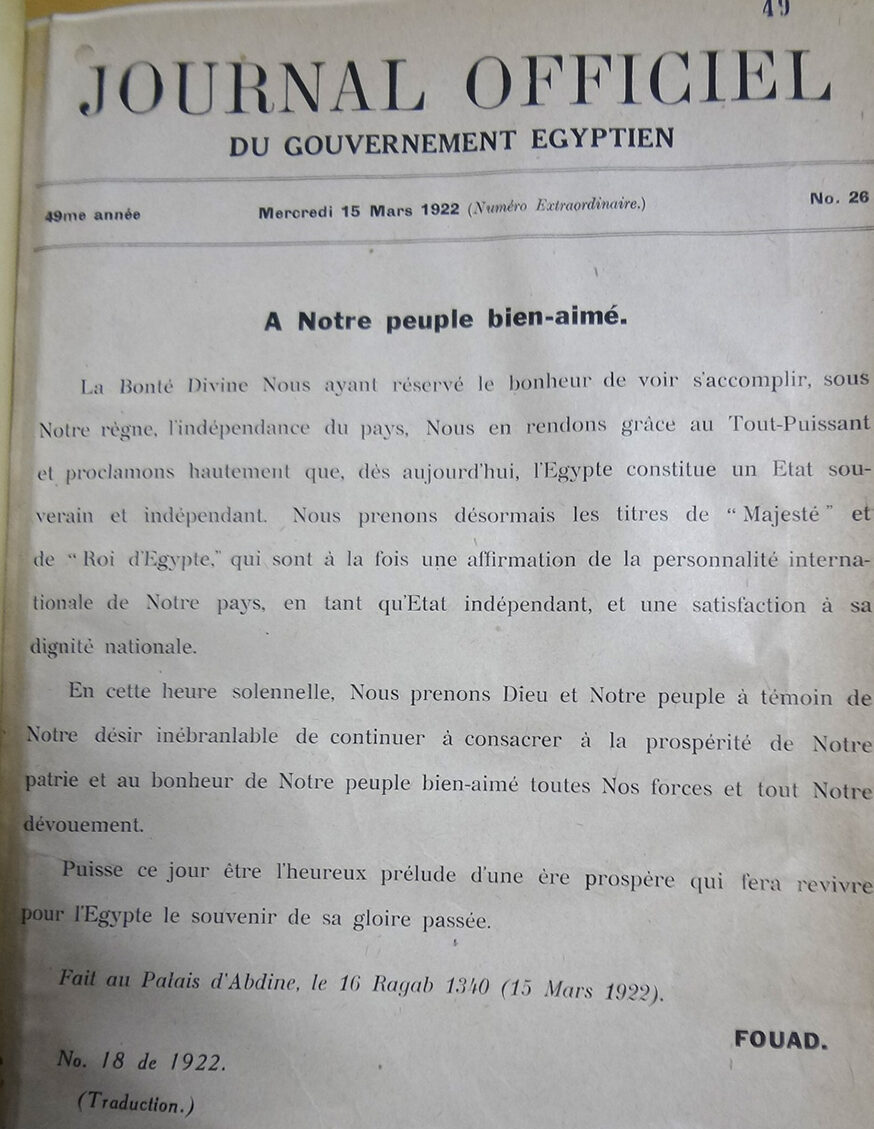

On 15 March, Sultan Fuad became King Fuad I. Egypt had become an independent constitutional monarchy. The first elections were held on 12 January 1924 and the Wafd won a landslide victory. Saad Zaghloul, who had been released from exile in March 1923, became the first elected head of government of Independent Egypt.

In 1922, the British hadn’t been completely driven out of Egypt, and independence remained imperfect. But national unity had prevailed.

This article has been incredibly insightful in helping me understand why my British subject great grandparents decided to leave Egypt for good. They lived in Port Said until 1910.