Friday 10 May 1940 was surely one of the most dramatic days in modern history. At dawn, Hitler invaded the Low Countries – Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – and France. The ‘phoney war’, the eight-month period at the start of the Second World War, during which military operations in the West were limited, was well and truly over. That evening, Winston Churchill ‘walked with destiny’, becoming Prime Minister at the age of 65.

After British Forces failed in their attempt to stop the German occupation of Norway in April 1940, and while Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty might have expected to be in the firing line, it was Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain who faced a barrage of ferocious criticism in the House of Commons during the Norway debate. Chamberlain lost the support of a significant number of MPs in his National Government: in a division of the House (effectively a vote of confidence) on 8 May, the Government majority was reduced from over 200 to 81.

Crucial meetings

The next day Chamberlain met with Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, and agreed that the Labour and Liberal parties should be invited into the Government. Subsequently, Labour Leader Clement Attlee and his deputy, Arthur Greenwood, agreed to go to Bournemouth to put two questions to Labour’s National Executive Committee: (1) ‘Would they enter a Government under the present Prime Minister?’ (2) ‘Would they come in under someone else?’[ref]Churchill: Walking With Destiny, Andrew Roberts (Allen Lane, 2018), p. 503[/ref] Attlee would relay the answers to No. 10 the next day by telephone.

Chamberlain’s preferred successor was Halifax, but he lost the opportunity to shape events during a further crucial meeting on 9 May. Winston Churchill, Lord Halifax (Foreign Secretary), Neville Chamberlain and Captain David Margesson (Chief Whip) held a meeting to discuss who should become Prime Minister in the event of Labour refusing to join the Government under Neville Chamberlain.

Accounts of this meeting vary. Churchill always maintained that he kept silent at a crucial juncture, and that Halifax discounted himself from the premiership because of his peerage. The meeting ended with an agreement that Chamberlain would advise the King to send for Churchill if Labour relayed the message the next day that they refused to enter the Government under Chamberlain’s leadership.

Reacting to the emergency

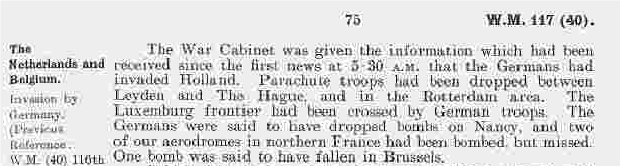

So, as 10 May dawned, Chamberlain was still Prime Minister. The intensity of this time is reflected in the fact that there were three War Cabinet meetings that day (though a high frequency of meetings became a regular feature in May 1940). The first meeting began unusually early, at 08:00. The reason for this was obvious – the War Cabinet was reacting to the news of the sudden German offensive.

The minutes of the War Cabinet meetings are interesting because several of the items which were discussed that day were to become recurring themes over the next few months, and in some cases were issues for the remainder of the war. This is particularly true of the development of the bombing campaign during a new era of total war. The historian can see the threads emerging in these documents.

At the 08:00 meeting the Air Staff were authorised to carry out air attacks on military targets west of the Rhine using part of the heavy bomber force; discretion was given to divert a Hurricane Squadron to France in accordance with a plan to despatch four such squadrons ‘if the situation in this country permitted it’ (i.e. if Britain could spare them); coast defences and home forces were put at immediate readiness, and the public ‘might be warned to look to the state of their gas masks’.

Working at full tilt

The next War Cabinet meeting, held at 11:30, was particularly busy. Various messages were received and read out during the course of the meeting – this was the Cabinet working at full tilt, akin to an emergency War Room – with added debate. One of the issues discussed was, essentially – how should Britain react if the Germans bomb the civilian population of Belgium? Chamberlain then posed the question – what if the bombing of civilians was incidental to a military target? He felt that ‘the essential thing was not to do anything which could render us liable to be accused of having initiated unrestricted bombing’. He was consistent in his strong aversion to the horrors of war. A decision on beginning bombing on military targets in the Ruhr was deferred until the late afternoon.

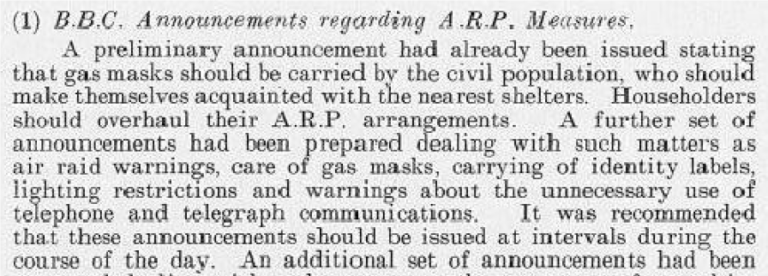

Concern about events in the Low Countries and France was intertwined with issues on the Home Front. The vigorous application of measures on the domestic front was Chamberlain’s greatest strength, something that should be taken into account when appraising his record. The BBC had begun to make announcements about Air Raid Precautions.

At the 16:30 War Cabinet meeting, among other matters, it was reported that the advance of our troops into Belgium was going according to plan. Under the chilling agenda item ‘Invasion of Great Britain’, it was noted that instructions would be issued to troops about the action they should take against parachutists attempting to land in this country. There was a further debate about the use of the heavy bombing force; Chamberlain wrapped this up by postponing an attack on objectives east of the Rhine, for at least 24 hours – it could be argued that this reflected his cautious approach to the prosecution of the war, though it should be noted that Churchill agreed with the decision.

Hopes dashed

Some historians have speculated that Chamberlain entertained hopes that his Premiership might be saved because of the German offensive – that support for him to stay at the helm might prevail. There is some evidence for this: on 10 May Chamberlain wrote to Beaverbrook ‘we cannot consider changes in the Government while we are in the throes of battle’, and over lunch at the Dorchester, which he managed to fit in between his Cabinet meetings, Chamberlain was ‘calm and charming and showed little effects of the battle that had been waging about him.’[ref]Neville Chamberlain, A Biography, Robert Self, (Routledge, 2016), p. 430[/ref] There remained a fiercely loyal (and vocal) grouping of MPs who supported the Prime Minister, who would be horrified at the prospect of Churchill reaching the apex of political power, as they regarded him as volatile and lacking in judgement.

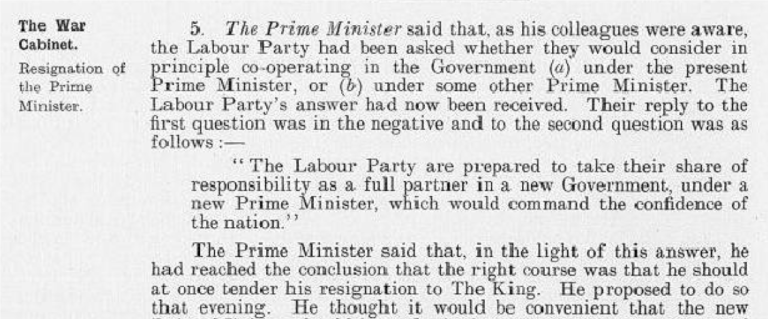

However, any such hopes that Chamberlain might have nurtured would have evaporated immediately when Attlee phoned No. 10 at 16:45 (it is unclear as to whether Chamberlain took the call or whether the message was passed to him). The outcome was recorded in Agenda Item 5.

The die was cast. In accordance with protocol, Churchill was not named as the new prospective Prime Minister at the meeting, but he knew his time had come. An hour after Attlee’s call, Chamberlain went to the Palace to resign, and Churchill was sent for to ‘kiss hands’ with the King, signifying his appointment as Prime Minister. Churchill later wrote about this time: ‘I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial…I was sure I should not fail’.

Cabinet Minutes and Memoranda are available to download at: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers.

Chamberlain would have been a total disaster if he stayed in office, mind you Churchill was responsible for the pullout out of Bergen (Norway) in 1940 after Dunkirk and also the campaign at Gallipoli during the First World War. The effect of Churchill in 1940 was that civil servants were seen hurrying down corridors now, quite right!.

I should have, of course, had said the pullout from Narvik in Norway not Bergen!. The museum in Narvik is in my view quite sharp (critical) over the withdrawal of British troops from Narvik, quite so.

Can it be argued, that if the War Cabinet had approved an attack by the heavy bombers in the Ruhr, on 10 May, and not postponed it for 24 hours the war would have progressed differently?