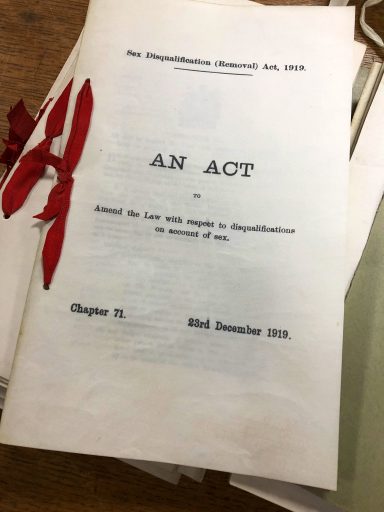

Last year we celebrated the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which gave some women the right to vote for the first time. However, the Act was only the first step and led to many other victories for women’s rights. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 was the next important milestone but it is now largely forgotten. The purpose of the Act was clear, that:

A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation 1.

Although the Act allowed women to enter the professions, including the law and civil service, was this the reality? The limitations of the Act have tended to overshadow its successes, but a century after it was passed historians, such as Dr Mari Takayanagi, are rectifying its reputation 2.

How did the Bill come about?

The bill came about following the introduction of a more radical bill: The Women’s Emancipation Bill. The bill was introduced by Labour MP Benjamin Spoor on 21 March 1919 3. Not only would this bill allow women to enter the professions, but it would also allow women to vote on the same terms as men and enable women to sit in the House of Lords 4.

Although the bill passed successfully through the House of Commons, the Government put an end to it and created its own bill: The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill.

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, 1919. Catalogue ref: C 65/6404

What was in the Sex Disqualification Removal Bill?

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill continued to push for women’s rights within the professions. However, women would not be able to vote on the same terms as men until the 1928 Equal Franchise Act and could not sit in the House of Lords until 1958.

The Government focused on the professions, but during the discussions surrounding the Bill, there were suggestions about limiting the Act further. There were concerns about whether the Bill should include the words ‘or marriage’, as ‘A married woman is incapable of acting as a next friend or guardian ad listem’ 5.

Moreover, there were concerns that women in the civil service would be conflicted between their personal life and their work: ‘Women Civil Servants if married either must deliberately endeavour to remain childless or will be forced to neglect either their children or their duties to the Service or both’ 6.

Nonetheless, the phrase was added to the Bill and the Act was passed on 23 December 1919. The Act stated that a person would not be disqualified by sex or marriage from entering the professions, with the following provisos:

- Proviso A: Permitted the civil service to create their own regulations regarding women’s employment.

- Proviso B: Permitted judges to have single sex juries.

What were the results of the Act?

Successes

Women could now become accountants, vets, solicitors, barristers, magistrates and sit on a jury.

Helena Normanton, first woman to be admitted to the Inns of Court. London School of Economics, The Women’s Library Collection, ref: 7HLN/E/13

The greatest victory for women was in the legal profession. Women had been studying law and trying to break into the legal profession from the end of the 19th century. For example, Eliza Orme applied to take the Law Society’s exams to become a solicitor in 1879, but was refused. She eventually became the first woman to earn a law degree in England from the University of London in 1888 7.

Women continued to fight to join the legal profession by applying to the Inns of Court or Law Society, like Bertha Cave in 1903, or by raising legal cases against the Society, such as Gwyneth Bebb in 1913 8.

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was a true and well-deserved win for women in the legal profession 9. Only a day after the Act was passed, Helena Normanton was the first woman to be admitted to the Inns of Court on 24 December 1919 10.

Likewise, women could become magistrates. As this role did not require any training or qualifications, women were able to become magistrates and Justices of the Peace very quickly. On 24 December, seven women became Justices of the Peace and shortly after Miss Gertrude Mary Tuckwell became the first magistrate for London 11. The Government also emphasised the benefits of female magistrates, recognising that they could be beneficial in children’s cases – an area women should supposedly have been largely familiar with.

Limitations

Despite these victories, historians have let the Act be overshadowed by its shortcomings.

Along with the equal franchise and a woman’s right to sit in the House of Lords, there was a failure to remove the marriage bar for the civil service.

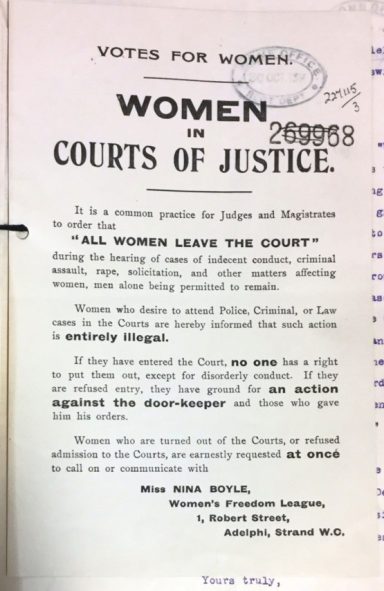

There had been calls for women to sit on juries from at least 1913. The Women’s Freedom League complained to the Home Office about the exclusion of women during sexual offences trials. Catalogue ref: HO 45/13321

The marriage bar was not a piece of legislation but a regulation employers wrote into their contracts. The Act was passed with proviso A which gave employers the right to create their own regulations regarding women’s employment. Consequently, the civil service maintained its strict marriage bar, stopping women from working once they had married. Women were also unable to enter certain positions in the civil service, including the diplomatic and foreign service, as well as the higher positions.

Similarly, there were limitations in other professions. Despite early discussions mentioning the role of women in ecclesiastical vocations, the Act did not change the fact that women could not enter the church or armed forces 12.

Judges could also request that no women be on a jury if they thought it would hinder the trial. Although the Act removed disqualifications, it did not create new rights for women and these decisions were still reliant on the professional bodies.

There had been long-standing calls for women to be on juries, including by the Women’s Freedom League in 1913. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 finally gave women a role on juries to actually determine whether an accused person was guilty. However, judges were allowed to request single sex juries under the act and jurors had to satisfy a property qualification, which often excluded women. More about this complex history can be read on the First 100 Years website.

Nonetheless, the Act was an important first step for women in the professions, allowing them to take on new and exciting roles that had previously been reserved for men. This act shows the increasing emphasis a female electorate gave to progressive legislation that would affect women’s lives. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 was just one example of the legislation that was to slowly develop over the next decade.

On the 23 December 2019, we should all remember the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 and celebrate how far we’ve come, but also consider how far we still have to go.

The Citizens project

This blog has drawn on many of the key points mentioned by Dr Mari Takayanagi, Katie Broomfield, Dr Helen Glew and Dr Anne Logan in videos from the Citizen’s project, which can be found on their YouTube channel.

The Citizens project is led by Royal Holloway, University of London, and charts the history of liberty, protest and reform from Magna Carta to the Suffragettes and beyond. Elena Rossi is a Citizens project intern.

Notes:

- The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, 1919. Catalogue ref: C 65/6404. Chancery: Parliament Rolls, c 58-85. Date: 9 & 10 Geo V. ↩

- Mari Takayanagi, ‘Parliament and Women, c.1900-1945’ (PhD thesis, King’s College, London, 2012). ↩

- Ibid. p. 39. ↩

- Record Type: Memorandum. Former Reference: GT 7239. Title: Women’s Emancipation Bill. Author: Austen Chamberlain. 8 May 1919. Reference: CAB 24/79/39. ↩

- Record Type: Memorandum. Former Reference: GT 7502. Title: Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill. Author: Gordon Hewart. 18 June 1919. Reference: CAB 24/82/2. ↩

- Record Type: Memorandum. Former Reference: GT 7239. Title: Women’s Emancipation Bill. Author: Austen Chamberlain. 8 May 1919. Reference: CAB 24/79/39. ↩

- Howsam, L. (2004, September 23). Orme, Eliza (1848-1937), social activist and lawyer. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 17 Dec. 2019, from www.oxforddnb.com. ↩

- https://first100years.org.uk/digital-museum/timeline/. ↩

- For more on women in the legal profession see Lucinda Acland and Katie Broomfield, ‘First: 100 Years of Women in Law’ (London, 2019). ↩

- Workman, J. (2011, September 22). Normanton, Helena Florence (1882-1957), barrister and feminist campaigner. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 17 Dec. 2019, from www.oxforddnb.com. ↩

- https://first100years.org.uk/gertrude-tuckwell-londons-first-woman-magistrate/. ↩

- Record Type: Memorandum. Former Reference: GT 7399. Title: Disqualification of Women (Removal) Bill. Author: Attorney General. 2 June 1919. Reference: CAB 24/80/100. ↩