Beyond 2022: The Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland is making available replacements for documents lost in the explosion at the Four Courts building in Dublin on 30 June 1922. Most material is being reconstructed at series or, even higher, at collection level. There are some collections though for which a more complete reconstruction is possible.

In this post, Dr Elizabeth Biggs, National Archives Research Fellow on the Beyond 2022 Medieval Irish Exchequer ‘Gold Seam’ project, describes the medieval riches which survived in the UK’s national archives and discusses the project to make their contents accessible to the public.

Among the records of the English Exchequer (the government department responsible for royal finances and taxation) is a treasure trove of original medieval documents from Ireland. Conquered partially by English and other settlers from the late 1160s, Ireland became one of the key dominions of medieval English kings, over which they asserted a lordship mandated by papal favour. In 1293, after a series of corruption scandals, King Edward I (1272-1307) ordered that the business of the Irish Exchequer and its chief official, the Treasurer of Ireland, should be audited.

For over 150 years, records were sent from Dublin to London to be audited at the English Exchequer in Westminster Palace. Two copies of the financial records of the Irish Exchequer – those dealing with receipts coming in and payments going out – were sent across the Irish Sea along with the evidence that supported each line of the accounts. These included the tally sticks, cut pieces of wood with notches marking the amounts received from those who owed money to the king. Once the English clerks at Westminster were happy, one copy of the records was kept in London in case of further questions and the other appears to have been sent back to Dublin. These audits were supposed to be yearly events, but more often they happened when the Treasurer finished his term of office every five years or so.

In theory then, the audit process resulted in two parallel archives – one in Dublin and one in London. Although many original records had already been lost over intervening centuries, fire destroyed the surviving rolls in Dublin in 1922. By good fortune, most of the records that came to London made it safely through the centuries to end up with the rest of the English Exchequer’s archives here at Kew.

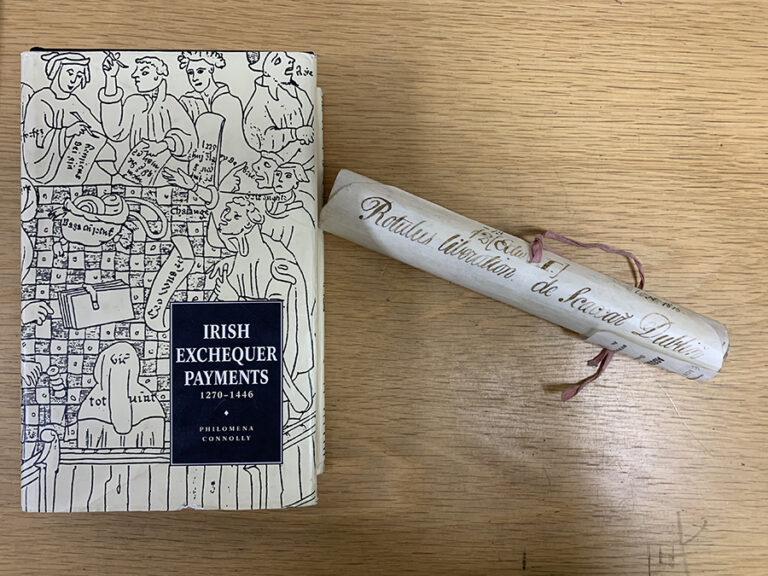

There are 400 or so files in the E 101 series that relate to medieval Ireland, covering most of the years 1270 to 1446 with relatively few gaps. These documents and the reasons for their presence at Kew have been well known to historians, but they have not been published in full. H S Sweetman in the late 19th century published extracts for the period up to 1301 (see footnote 1). Twenty years ago, Dr Philomena Connolly, archivist and medieval records expert at The National Archives of Ireland, published a translation of one section, the 500 or so membranes that contained the payments out of the Irish Exchequer. Her ‘Irish Exchequer Payments, 1270-1446’ is a crucial resource for understanding the lives of people living in Ireland seven centuries ago (footnote 2).

Now for the first time as one of the Gold Seams of the Beyond 2022 project, the receipt rolls, the payments into the Exchequer, will be made available for the public and researchers in translation. The edition will initially extend from c. 1270 to c. 1315 – the year of a cataclysmic climatic episode and a Scottish invasion of Ireland that prompted famine and suffering on an unprecedented scale. Translations can be consulted alongside the digital images of the original rolls. For more on the conservation and digitisation processes involved in making medieval records available, re-join us tomorrow for a fascinating blog by our colleague Rhea Evers.

What kind of things can you find in the Irish Exchequer records? These are records of English colonial government and they tell us about what it was like to live under English rule in Ireland. We see payments from and to English officials and settlers, individuals of Irish and mixed ethnicity, and people from all over Europe who lived and worked on the island of Ireland. For example, Italian merchants from Lucca and Florence traded wine and wool and reaped the rewards of the Irish customs. These were granted to them by Edward I, grateful for their bankrolling of his expansive military campaigns. In far-flung areas, such as Kerry on the west coast, we find people slipping out of the reach of English government. The clerks make comments like ‘on account of the waste of the land’ when an expected payment failed to materialise. War was a constant backdrop, and taxes were often levied for military expeditions against Irish kings. But we also see family connections and friendships as well as the mischances of everyday life.

Women play a prominent part in these kind of records. Juliana de Howth (perhaps from one of Dublin’s northern suburbs) pays a fine for short-changing her customers’ ale in Dublin. Sarah de Kilsalham takes over responsibility for her late husband’s lands and then pays for licence to remarry. Irish men and women pay to have access to English law, from which they were usually debarred. Lawsuits are begun and ended.

These records are tantalising glimpses into life in Ireland 700 years ago. But it is by combining them with other records that we can start to build up an even more complete picture of medieval Ireland. By making available on the Gold Seam’s webpages Connolly’s edition of the issue rolls, our edition of the receipt rolls and the original images, we hope that people will be able to combine these records in new ways. For the first time, they will be full-text searchable. You will be able to see all the instances of particular places or names. A damaged name, such as ‘Ismaena’, whose family name is lost, might now be linked to other records at The National Archives and around the world. We’ve begun that work by building a knowledge graph, which uses information drawn from Irish Exchequer Payments, to classify historical information in a way that is useful to researchers.

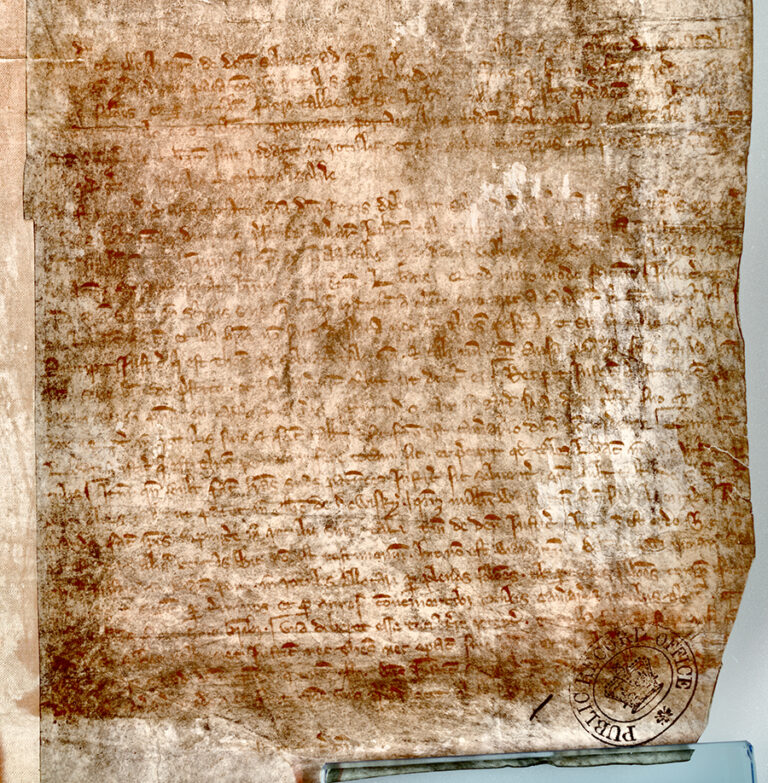

We know about more links that we will be able to build in the future that will connect The National Archives’ medieval Irish records with other collections (footnote 3). For example, the British Library holds at least two items which were written at the medieval Irish Exchequer. The National Archives of Ireland holds two surviving memoranda rolls of the Irish Exchequer which survived the fire in 1922. Now researchers working with these documents can cross-reference them against the editions and images of the material at Kew. But we can also do more with technology. The rolls and other documentation required conservation and care before they could be digitised. The National Archives’ Collection Care department, particularly Dr Lucia Pereira Pardo, were also able to use the medieval Exchequer materials for further research. New scientific techniques, such as X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) scanning, have the potential to make faded or damaged text legible. Trials of the XRF scanning brought back words lost to damage well before the 19th-century work of Sweetman, enhancing our knowledge about medieval Ireland, letter by letter.

You can find the Medieval Exchequer Gold Seam documents in the Virtual Treasury’s database, with the translations linked to the digitised originals. The issue rolls cover 1270 to 1446 and the receipt rolls cover 1270 to 1315, and more are to come. You can also find historical background and highlights on the Gold Seam’s webpages.

Footnotes

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland Preserved in Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, London, 1172-1307, ed. H S Sweetman & G F Handcock, 5 volumes (London, 1875-86).

- Irish Exchequer Payments, 1270-1446, ed. Philomena Connolly (Dublin, 1998).

- For a broad overview of The National Archives’ medieval Irish collections, and some sample summaries, see Paul Dryburgh & Brendan Smith, A Handbook and Select Calendar of Sources for Medieval Ireland in the National Archives of the United Kingdom (Dublin, 2004).