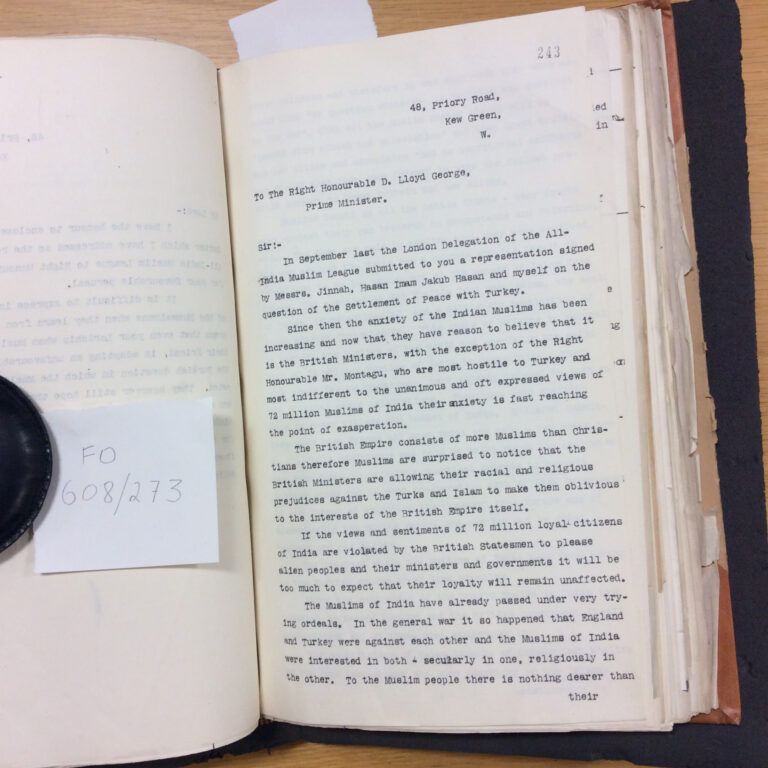

Among the vast collection of documents relating to the fallout from the First World War is one letter from Ghulam Muhammad Khan Bhurgri to Prime Minister Lloyd George. Undated, the letter is filed away dated 7 January 1920. It is filed under the subject ‘Turkish Settlement’.

The opening paragraph of the letter immediately catches the reader’s attention when Mr Bhurgri refers to himself as being part of a delegation to London to discuss the settlement of peace with Turkey. The delegation includes the future founder of Pakistan, Mr Jinnah.

In September last the London Delegation of the All-India Muslim League submitted to you a representation signed by Messrs, Jinnah, Hassan Iman Jakub Hasan and myself on the question of the settlement of Peace with Turkey.

EXTRACT (opening paragraph of letter)

At the end of the First World War and the defeat of Turkey, Indian Muslim pressure for a fair and just settlement for the former Ottoman Empire was stepped up. Conscious of the importance of Turkey and the Ottoman Caliph to tens of millions of Muslims who were part of Britain’s Indian empire, Britain’s Viceroy in India, Lord Hardinge, had advised the government in 1914 before the start of the First World War that it should declare itself the greatest Muslim power. The Ottoman Empire was about to join the war on the German side, and the pre-eminent concern was that both would turn nearly half of the British Empire’s Muslim population, who were Indian, against the British.

Muslims played a significant role in the First World War, and keeping them on side was important. At the start of the war Indians came out in support of Britain, and Indian Muslims, such as students at India’s Aligarh Muslim University, offered to fight. Muslims in Britain at the time also announced their support. An editorial in The Islamic Review, the newspaper of the Woking mosque, responded to the claim that Britain was the greatest Muslim power with a comment piece in its September 1914 edition announcing:

‘Great Britain is the greatest Muslim Power of the present age, and is referred to as such by Muslim writers: therefore, in supporting Great Britain we support our own Muslim Government.’

The Islamic Review, September 1914

A significant proportion of Indian troops fighting in the First World War were Muslim and they saw action in theatres of war including France, Belgium, Gallipoli, East Africa, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia (see here for further information).

A fine balance was sought to be struck between the needs to recruit and employ Muslim troops in battle with their religious and cultural sensibilities. This balance was largely maintained over the course of the war. However, the end of the war, as in many other instances, marked a shift in the attitudes of Britain’s colonial subjects.

In India, Gandhi, an advocate for supporting the war in the earlier days, shifted and by the end of the war had become an outspoken opponent of British rule. He was joined in his efforts to challenge British rule by India’s growing Khilafat Movement*, which sought among a number of its demands the retention of the Ottoman Caliph as head of the Muslim world. At the same time, opinions in Britain about Turkey had shifted, and from the top down there was a markedly less tolerant tone towards Turkey. The lines were drawn for a battle to win the peace.

G M Bhughri’s letter set in this light marks an important turning point, as the fragile unity of the war years was superseded by a new and altogether more serious threat to British rule in India: a threat not only by extremists but also more moderate voices. Bhughri was one of these moderate voices whose letter, while maintaining a respectful tone, also hints at the threat that may come: that Muslims, having served loyally, now feel that they are on the point of being betrayed.

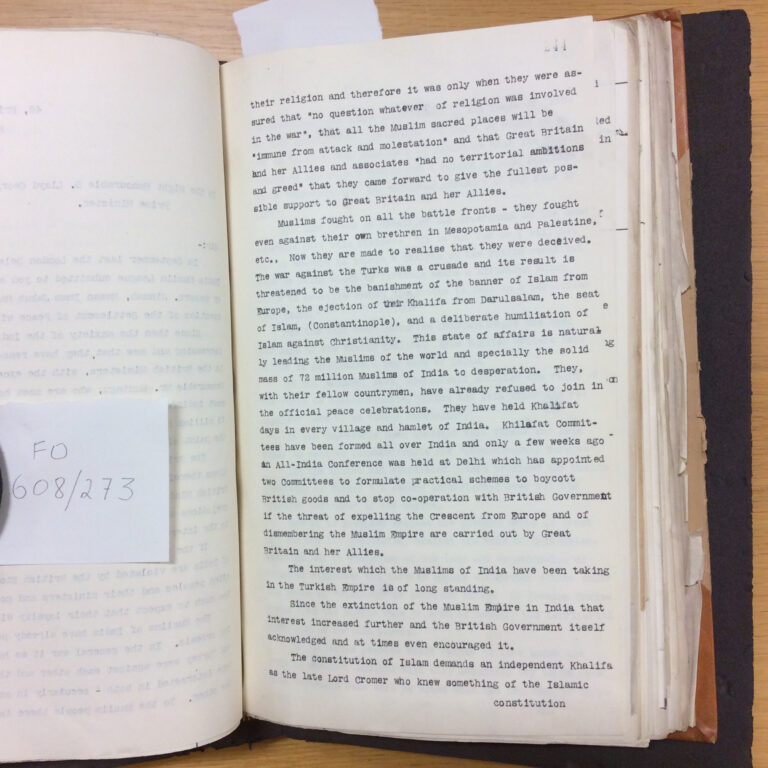

Muslims fought on all the battle fronts – they fought even against their own brethren in Mesopotamia and Palestine, etc. Now they are made to realise that they were deceived. The war against the Turks was a crusade and its result is threatened to be the banishment of the banner of Islam from Europe, the ejection of their Khalifa from Darulsalem, the seat of Islam (Constantinople), and a deliberate humiliation of Islam against Christianity.

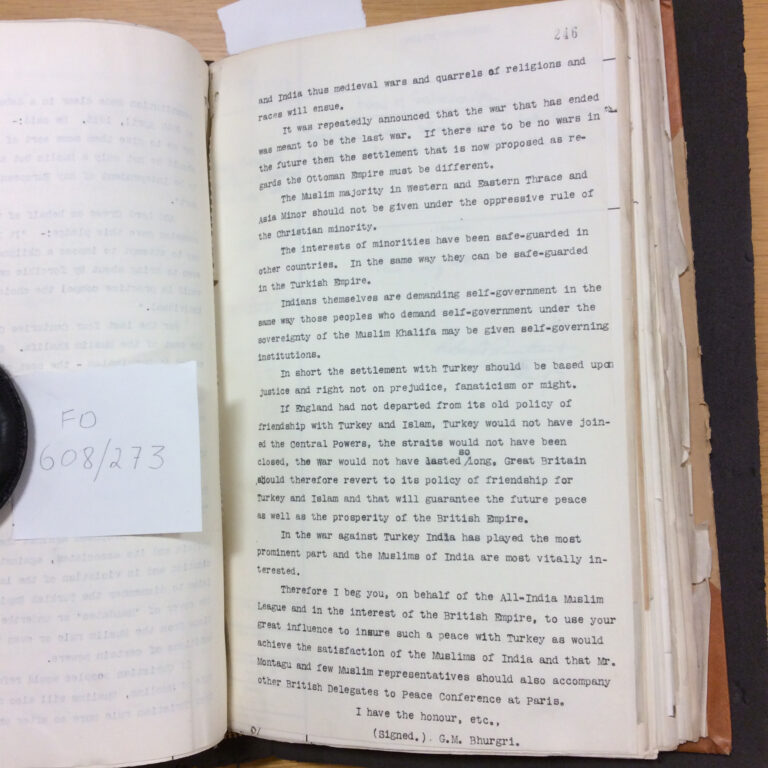

G M Bhughri’s letter also gives us an insight into some of the major areas of focus for emerging nationalist and anti-colonial voices at the end of the war, including his reference to the interests of minorities, the use of protest and non-cooperation and demands for self-government. The visit by the delegation of which G M Bhughri was a part achieved very little, as did a subsequent attempt by Mr Jinnah to have a private meeting with the Prime Minister Lloyd George. By September 1919 the Muslim League had resolved to hold an All-India Khilafat Day on October 17 with the aim of boycotting British goods and protesting at the threat posed to Turkey.

Indians themselves are demanding self-government in the same way those people who demand self-government under the sovereignty of the Muslim Khalifa may be given self-governing institutions.

In short the settlement with Turkey should be based upon justice and right not on prejudice, fanaticism or might.

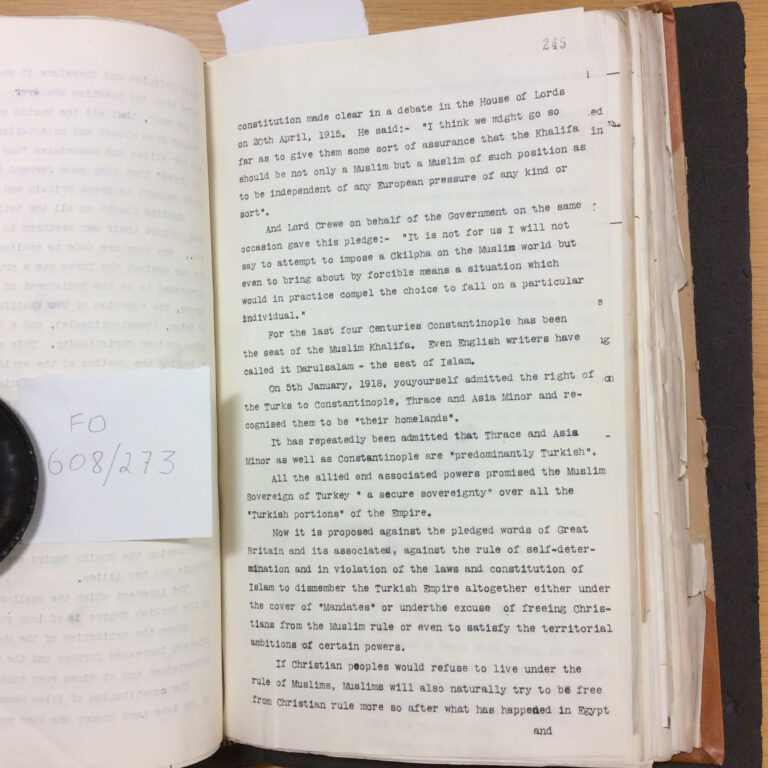

The British government’s view was that the principle of self-determination which was applied to the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to apply equally in the case of Turkey, and this meant the inevitable break-up of the Ottoman Empire. The tough stance adopted echoed a wider public view at the time that the Khilafat Movement was a political movement and unrepresentative of wider Muslim opinion.

Download a transcript of the letter

On a more prosaic level, G M Bhughri’s visit to London in May 1919 as part of the Muslim League delegation and his stay in Kew, only a stone’s throw from where today his letter is filed under our Foreign Office collection, raises the question: why did he decide to stay in Kew?

*The Khilafat Movement was a campaign by Indian Muslim leaders drawing on religious and political symbols aimed at unifying the Muslim community in India behind a wider Indian nationalist movement.

Further reading

Naeem Qureshi, ‘Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918-24’ (1999)

Gail Minault, ‘The Khilafat Movement’ (1982)