Content note: this blog draws on contemporary sources which contain terms for Japanese people now considered offensive. The author has expanded these derogatory shortenings in his quotes from the material.

The ‘Forgotten Army’

They have been called the ‘Forgotten Army’ – the British Fourteenth Army who, in 1944 and 1945, fought a brutal and gruelling war in the jungles of Burma (now Myanmar) but who largely went uncelebrated in Britain. This was partly because, as my colleague Katherine has pointed out, even in 1945 the Ministry of Information found that only around half the population had a basic grasp of the situation of the war in Asia.

The Fourteenth Army’s contribution to the defeat of the Japanese war machine has received some recognition in recent months due to it counting Captain Sir Tom Moore as one its veterans, him having served in the 146th Regiment Royal Armoured Corps.

But the Fourteenth Army is also noteworthy for its truly international make up and size: over a million men in 1945, drawn from every corner of the Commonwealth. There were many Indian and Australian units in the Army but also soldiers from three African divisions: the 81st and 82nd West African Divisions, and 11th (East Africa) Division.

In this blog I would like to focus on the bravery and contribution of the men of the 81st and 82nd West African Divisions, particularly the men of the 2nd West African Infantry Brigade as they sought to assist the taking of Southern Burma from the Japanese, one hill at a time, in brutal close quarters fighting in early 1945.

I’d like to focus too on how these men received the news that they would not have to fight again, as VJ Day was announced while they were in their rainy season quarters.

The Fourteenth Army and the 1944-45 Burma campaign

The Burma campaign was one of the longest in the Second World War – in part because the Burmese rainy season, which runs from May to October, made fighting sustained actions impossible for much of the year, but also because of the dense vegetation which covered much of this theatre of war.

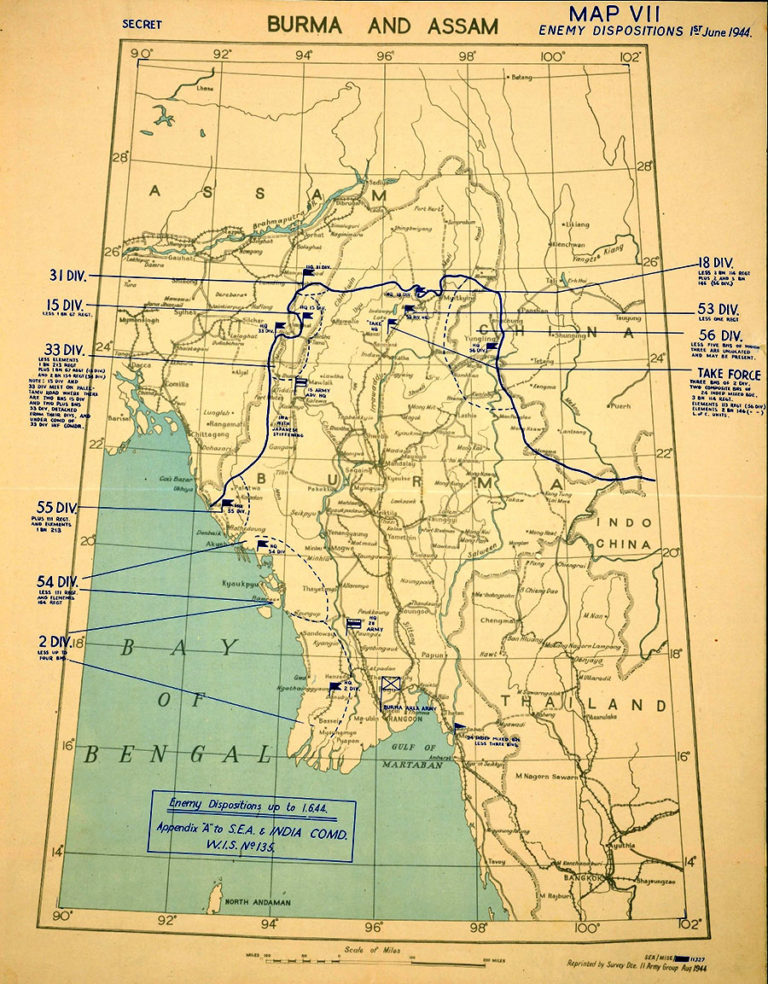

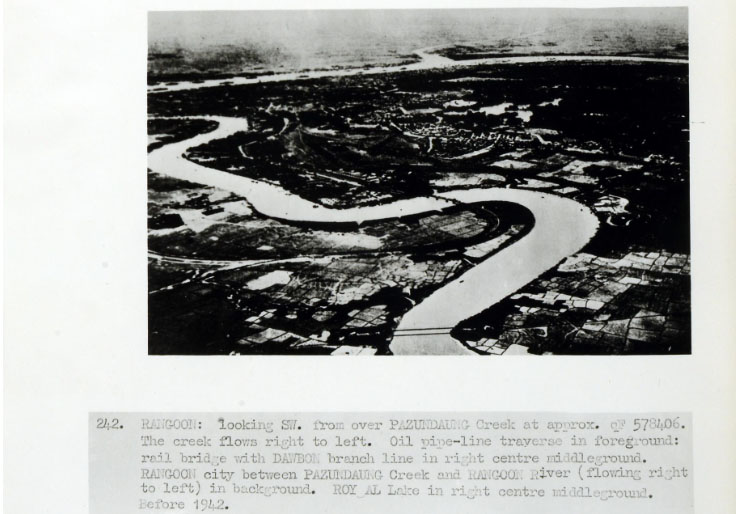

Japanese forces had captured Burma in 1942, causing the British administration there to flee to India. A new government had been installed that was sympathetic to the Japanese. Japanese forces and their allies had fended off Allied offensives in 1943, and at the beginning of 1944 they decided that attack was the best form of defence and launched a disastrous attack towards India. In the 1944-45 campaigning season the British and their Commonwealth, American and Chinese allies were determined to recapture Burma.

As the rains ceased in late 1944, the offensive began. XV Corps, which included the 2nd West African Brigade, were involved in the invasion of the coastal Arakan region (now Rakhine State).

2nd West African Brigade

From December 1944 the 2nd Brigade, part of the 82nd West African Division, was engaged in fighting across the coastal Arakan region, heading towards the area around Taungup (Toungup).

Their war diaries, held by The National Archives (WO 172/9572), give us an idea of the ever present danger of enemy attack in the region’s dense terrain, where the fronts of the brigade and its adversaries from the Japanese 54th Division were so close together and shifting.

The diaries show how the supply and communication lines of the brigade were continuously strained and under threat. In March the diary records that roving Japanese patrols sought to ‘all day cut our Lines of Communication’.

Also clear is how the remote location of the unit made getting enough rations and medical attention for the troops tricky – the diary often indicates that the Japanese troops made efforts to disrupt food supply drops by Allied plans (which was how much of the Fourteenth Army received its supplies).

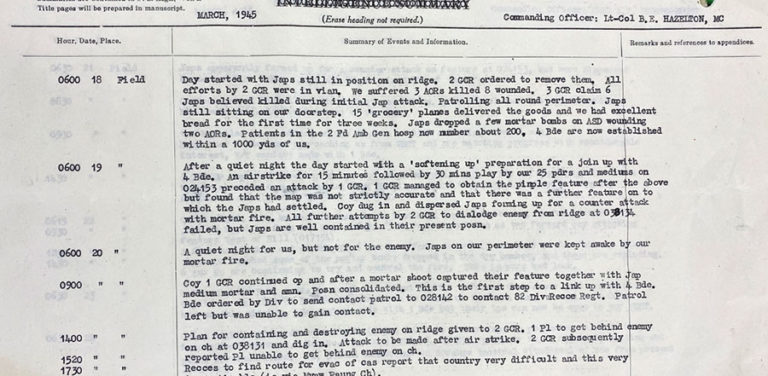

On 15 March, after a week of heavy fighting attempting to take the road to Taungup, the officer writing the diary is pleased to note that despite ‘the Japanese still sitting on our doorstep…15 “grocery” planes delivered the goods and we had excellent bread for the first time for three weeks’. Casualties in the brigade’s field hospital were around 200 though, he noted, a sign of the toll that the near constant fighting in early March had taken.

So intense was the fighting that not even the brigade’s senior officers within their headquarters were any safer than their troops. The diary records how, on the 15 March 1945, the HQ was hit by Japanese shelling, killing three men and injuring the Commanding Officer Brigadier E Western, who had to be relieved of his duties.

What is striking about the brigade’s diary, and that of one of its units, the 3rd Gold Coast Regiment (WO 172/9625), is how often the ambush took the form of near point-blank ambush, and descended into hand-to-hand combat.

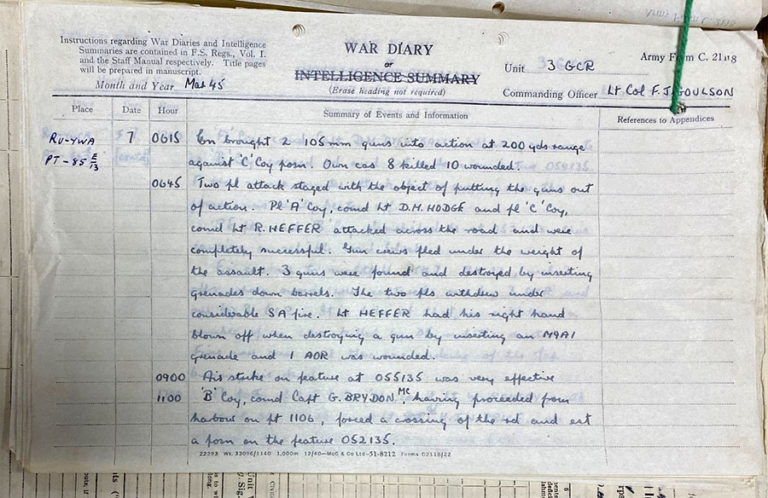

On the 7 March 1945 the 3rd Gold Coast Regiment was involved in particularly heavy fighting on what the brigade diary called a ‘great day’. Ambushed by three 105mm artillery guns at 200 yards (183 metres) range, eight men from D Company were killed and another 10 wounded.

The Company responded by launching a rapid charge of two platoons, led by a Lieutenant Heffer. The speed and ferocity of this counter attack was ‘completely successful’, the Japanese gun crews fleeing from the advancing Gold Coasters. Heffer and his men made good their work, destroying the guns by putting grenades down the barrels. But this rudimentary decommissioning was not without cost, as Heffer lost his right hand from the grenade blast.

The evening before in the same operation, the Gold Coasters had also been involved in achieving what was thought to be a first in the 1944-45 Arakan campaign – the capture of a Japanese tank. The diaries of the 3rd Gold Coast Regiment and the Brigade HQ tell how, having moved further up the road they were tasked with controlling, the men of the 4th Field Company West African Engineers laid anti-tank mines across the road to prevent a Japanese counter-attack.

They were prescient, as two tanks advanced towards them that evening. The first of these drove over a mine and was immobilised. Men from the 3rd Gold Coasters then advanced to strafe and grenade the tank, nearly completely destroying it.

West African honours

The bravery of the West African soldiers is evident from their war diaries, but The National Archives also holds records of individuals being honoured for great feats of courage.

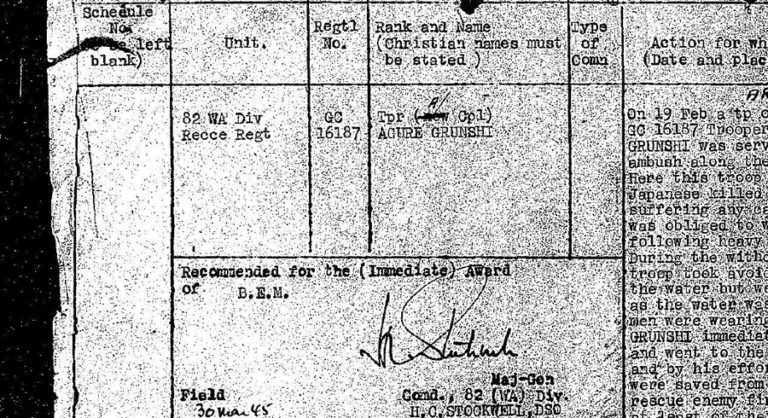

WO 373/40/140 contains the recommendation for a Military Medal awarded to Corporal Agure Grunshi of the 82nd (West African) Reconnaissance Regiment, part of the 82nd West African Division. In February 1945 during the Arakan campaign, Grunshi saved several of his comrades’ lives when they were attacked on patrol and jumped into a deep river while wearing full equipment to try to escape. He removed his equipment and saved six of eight men from drowning, all under sustained enemy fire.

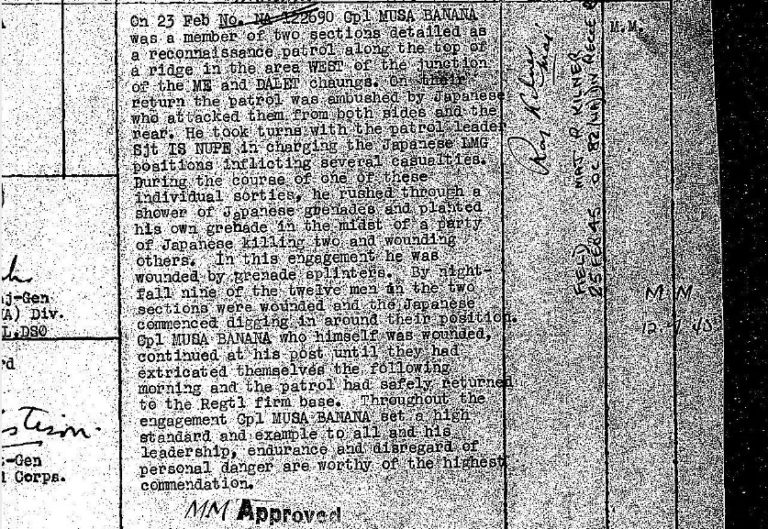

Corporal Musa Banana, again of the 82nd Reconnaissance Regiment, received a Military Medal for his actions also during the Arakan campaign. On 23 February Banana’s unit was on patrol when it was attacked from both sides and the rear. Together with his patrol sergeant, IS Nupe, Banana took turns charging a Japanese machine gun position to try to relieve his unit (WO 373/40/139).

At one point Banana ‘rushed through a shower of Japanese grenades and planted his own grenade in the midst of a party of Japanese, killing two and wounding others’. Despite in the course of this attack being wounded himself by grenade splinters, Banana continued to work through the night, until he and his comrades could retreat in an orderly fashion. His ‘leadership, endurance and disregard for personal danger’ were deemed ‘worthy of the highest commendation’.

‘Rumours of Japanese surrender were current and feeling was high’

The 2nd West African Brigade began withdrawing from active combat zones towards the end of March; after some reorganisation they focused principally on digging in and constructing their quarters for the rainy season (there is some talk on how well the gutters are holding up).

The brigade, and indeed the army, were preparing too for a resumption of fighting in the autumn, but they were given a reprieve by the end of the war on 15 August. The brigade’s diary betrays the officer writing’s anxiety for the end of the war. On 10 August it is noted that feeling around the possibility of a cessation of hostilities was running high. News among the troops in Burma on 11 August was ‘persistent and it seemed the end could not be long delayed’ – by this point the Japanese government had indicated its intention to surrender, but we cannot determine how much news had reached these troops, especially as on the 12th the officer records that the unit ‘still awaited’ news on the terms. However on the 15th the brigade received the news they hoped for. The day was ‘spent very quiet’, with the African troops ‘holding a Wassa’ in the evening 1.

The rest of the diary for August records the activities of soldiers no longer fixated by the concerns of war – thanksgiving services and sports days. The men of the brigade, transported from Ghana to the Burmese jungle to fight a war not of their making, must have been relieved that they would not have to fight again – it was the contributions and sacrifices of this truly global Forgotten Army that in part had made this peace possible.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

Notes:

- Despite researching, the author has been unable to determine exactly what kind of event a Wassa is. Any comments or suggestions are welcomed. ↩

“this blog draws on contemporary sources which contain terms for Japanese people now considered offensive. ”

no need to apologize. anyone who is knowledgeable about WW2 would know that such terms were used.

dont succumb to historic presentism

A very interesting read, in particular reflecting on how the action in Burma affected events elsewhere. It’s sad that Burma is still a place of conflict today. However I don’t think historical records should be censored in the name of political correctness.

What on earth were West African subjects of a European imperial power doing fighting to defend and restore that empire’s dominion in SE Asia ?

Many West Africans were comfortable with their British Empire status: Although I am personally most familiar with Sierra Leone, it was true perhaps to a lesser degree in Ghana and Nigeria.

Especially in SL the British were seen as liberators, ending the slave trade, and the climate there greatly restricted the number of British Imperialists keen to seek meagre gains at high risk of disease and death (fortunately diamonds had not yet been discovered.) Every office in the Sierra Leone Administration had been at least once occupied by a black individual with the sole exception of Leader of the Armed Forces. There was some racism, but always with widespread opposition except in the upper ranks of the army, and even there not vaguely resembling attitudes among Nazis and in Japan.

My own steward, Pa Dauda had fought in Burma with the King’s West African Rifles, and was proud of his career and highly held in our small town on that account.

I should perhaps say that I was there ten years after independence as a teacher in a school which had only one white (Lebanese) pupil and about 3 white teachers in a staff of 24 under an excellent black headmaster who took his chemistry degree in Hull.

This is such an interesting read as my grandad was part of the Australian army in this conflict. He died a few years before I was born and wouldn’t speak of what he had seen to my mum so we know very little.

There has been a lack of information generally in history (except “The World at War Series” on Thames TV) on the campaign and without the efforts of the RAF in dropping supplies which was critical to the campaign. I agree that censoring historical documents because of political correctness is wrong. The reason troops from over the Commonwealth fought for the ‘British Empire’ was it was seen as protecting ‘the Motherland’, just like ANZAC troops and the Canadians for example fought with Britain during the First World War.

The “World at War” episode on the Far East is very good, even after 45 years and is based on first hand accounts and Government documents which had recently been released in 1972.

Responding to Warwick, they were serving the British Empire, the biggest Empire the world has ever known. By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time, and by 1920, it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi), 24% of the Earth’s total land area. As a result, its political, legal, linguistic, and cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, the phrase “the empire on which the sun never sets” was often used to describe the British Empire, because its expanse around the globe meant that the sun was always shining on at least one of its territories. (Google)

Unfashionable and unacceptable as that might be in the 21st century, there were many from all over the world who were proud and keen to serve the Empire wherever they could and many paid with their lives, including in Burma.

The other reason Warwick, other than a sense of pride and duty to the British Empire, was that joining the Army offered a small wage and a square meal daily to young men from poor families. This also carried the risk of serving many miles from home and actually going into battle and dying.

Let’s remember all the brave men who were part of the ‘forgotten army’ fighting in Burma. My dad was with the Argylls & Sutherland Highlanders in Scotland and volunteered to go to Burma. He was sent to Nigeria where he was assigned to the West African 82nd Division and then shipped to India. From there the 82nd fought their way down to the Arakan in Burma and were instrumental defeating the Japanese.

The fighting in Burma was pure jungle warfare and these brave men suffered from so many diseases, tremendous heat, monsoons and a hidden enemy. The soldiers who became prisoners of war were treated worse than animals and suffered unimaginable horrors at the hands of the Japanese.

Those who returned home hardly spoke of the horrors they encountered and suffered for the rest of their lives. Dad came home all of 95lbs of him with malaria and beri beri and had horrific nightmares for the rest of his life. Let us never forget these brave men.

African troops in particular were felt to have more of an immunity to the effects of malaria prevalant in the theatre. West Africans in particular may also have been perceived as being well suited to Jungle warfare. The 2 West African Divisions (81st and 82nd) had a unique supply system based on human porters and as such were well suited to the extreme terrain of Burma – the inclusion of the 3rd West African Brigade (3 battalions of the Nigeria Regiment) amongst the 6 Chindit Brigades should not be underestimated. The remaining 5 W.A. Brigades saw service in the Arakan inland from the coastal region of Burma. By way of background, W. African troops had already seen service in E. Africa in 1940-41. One legacy of this is the naming of the El-Wak Military Barracks in Accra, Ghana after a Kenyan border town recaptured from the Italians end 1940. Post war agitation by WW2 veterans there were also arguably part of a movement which ultimately sought independance for Ghana, the first such nation from the British Empire in Africa….

Thank you for this research <My father was an officer with the West African soldiers . He would not talk about his war but this kind of information shows me that his war in Burma was more eventful than he ever admitted .

In the days of the WW1 and WW2 the Empire was a stabilizing force to millions of peoples and they looked to it as their government. You must not forget the benefits to them of an organized society where they could at least feel part of a grand organisation albeit that was using them. In return they fought for the Crown, very bravely . Sadly of course, after the Empire went chaos often came into its place and I wonder how many , if any, missed the days of the Empire?

Very interesting and rather unexpected indeed. On the pertinence of some people in the “British Empire and its Commonwealth” (as Churchill put it) rallying to defend it, there were excellent reasons. Recalling that people in the British realm were not of the Germanic Aryan “Master Race” nor had the Japanese ethnic superiority complex must be considered. Thus, many in the Empire and Commonwealth obviously made the decision that they were better off helping the Allies win the war. In the millions that volunteered, I can add my own French-Canadian nationalist father who joined the British Royal Air Force. Many years later, when I asked him why the British rather than the Canadian forces, he first answered that if he was going to be commanded “by the English, it would be the real English” and not English Canadians, adding that, most of all, “something had to be done about Hitler.”

My father, Captain Evan Stirling, RAMC, served in the 5th West African Field Ambulance from March 1945,supporting the 8 1st and 8 2nd West African divisions fighting the Japanese in Burma

My recent application for a Burma Star medal has been rejected as I am having difficulty proving the Field Ambulance served in Assam or Bengal to qualify for the award

His close association with the West African troops continued till the end of the war there and he was MO on one of the ships which repatriated these troops to Gold Coast and Nigeria in late 1945/early 1946

He was based in Lagos working as a Doctor waiting to be demobilised in September 1946,but was sadly killed in a services air crash in Nigeria in June 1946

Any further information about the 5th Field Ambulance service in India would be most welcome in order to appeal the rejection of the award of a Burma Star

Just watched 22.11.2020 film relating to the Forgotten Heroes (all the troops British and Commonwealth. including local boys and men) and the voluntary organisation caring for the veterans..Marvellous, must support! Wow age 90 plus men and families in Myanmar forgotten it seems but supported by these Few! The world owes them a great debt..

@Avril: Could you give details of that film, please – my wife’s father was with the RAF Regiment (ground support) and we know he was driving his lorry in India and Burma before being part of the Commonwealth Occupation Force in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

We know very little more than that. Like most, he never talked about it.

Very interesting maybe Captain Evan Stirling RAMC was aware of his death.

Frederick William Woodman

Service Number 5621147

Died Between 07/04/1945 and 08/04/1945 in Burma

Aged 23

Royal Artillery

attd. 22 Anti-Tank Regt.,

West African Artillery, R.W.A.F.F.

Mentioned in Despatches

Enlisted SEPTEMBER 1939 so was terrible for us all when he didn’t make it home to Devon.

Thank you for a really interesting site. I have been researching African soldiers in SE Asia 1900-1960. for an MRes. The fascinating point is that Africans were in the region for the entire period, in the Portuguese (Timor & Macau) , Dutch (Dutch East Indies), French (French Indochina) and British colonies (Burma and the Malayan Emergency). Some were taken as prisoners and were at Changi, the Burma Railway and even Japanese camps in Nagasaki! Sad that this story has been largely forgotten, and pleased your are addressing it. Africans were also taken prisoner by Ho Chih Minh’s forces and some defected to the communists.

The TV personality Griff Rhys Jones made a programme about his

father’s service in the Gold Coast Regiment, part of the 82nd Division, where he

was a medical officer, one of 26 Europeans in a battalion of 1200 African men. In

the programme, Burma, My Father and the Forgotten Army (2017), he interviewed

Kofi Nortai, a medical orderly who had joined up and served with his father Elwyn.

‘I was seventeen, eighteen years old. During that time, I knew nothing about the

war. I heard drumming – they were marching. They said anybody who wants to

join the army, they should come. Daybreak I go myself. I don’t tell my mother or

father’. Another film, possibly the only one from the period, 1945 is a Calling Blighty message film at the North West Film Archive https://www.nwfa.mmu.ac.uk/blighty/issue-record.php?IssueNo=199

It shows men of the 11th East Africa Division “fresh from their victories in the Kadaw Valley” . However it starts with an acted sequence where the men are told off in broken Swahili by a British officer, apparently for being lazy. The men also dance an Ngoma at the end. It looks to me as if the voiceover, added at the end, was an attempt to ameliorate the stereotypes inflicted by the unknown director.

my grandad served in Burma, welch regiment attd to 2nd West African Aux Group Nigeria Regiment, RWAFF, he was KIA 8th march 1945 so it has made interesting reading to see what they went through on a daily basis, you can see why not many of them wanted to talk about their experiences out there, they may be the forgotten army but they are all hero,s

My grand father was part of the 90 thousands African soldiers that fought the Japanese in Burma.

He returned to Nigeria safe!

It was fascinating to read the War Diary for the 3GCR for the 7th March 1945. I have looked into this action recently and perhaps could put it into some context. It records the setting up of a road block, to disrupt the Japanese supply lines, on the Tamandu/ An Road just south of Letmauk by the 2nd(WA) Brigade.

It initiated a very firm response from the Japanese. My late father, Lt Vere Tweedie MC, was a Company Commander of one of the companies of 2nd Battalion Gold Coast Regiment that were dug in on the side of the road. Opposite them, on the other side were two companies of 3GCR. Due to enemy action the situation had become untenable. On 8th March the order was given to withdraw to high ground to the west but, on the night of the 7th, the Japanese had infiltrated their positions and were well dug in in foxholes. 3GCR tried to withdraw across the road but were pinned down by heavy enemy fire. My father, after some contemplation, took some grenades and accompanied by a small group crossed the road towards the Japanese. Over a period of three hours, there ensued a game of cat and mouse as his group systematically found and cleared each of the foxholes. At some point my father lost a front tooth during the hand to hand fighting. Some Japanese were killed in their foxholes by the grenades but others, rather than die this way, chose to vacated their positions and put up a fight.

Eventually the task was completed and 3GCR managed to cross the road and withdraw to the jungle cloaked, high ground to the west, called points 1106 and 1269, and join up with the remainder of the 2nd(WA) Brigade. They were now surrounded by Japanese and all but cut off from the outside world, they did have supply drops from the air. The typed diary extract covering 18th to 20th March is from this period. It was not until after some 16 days that on the 24th March that they were relieved and over two hundred of their wounded evacuated.

You can find the Japanese point of view http://ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Japan/Monos/pdfs/JM-132/JM-132.pdf Pages 83 and 84

does anyone know or have connections with a john jack reid that was in burma at his time. he was a sergeant i believe. bury lancashire Fusilier

My father also served under the British Crown in Burma from the African Gold Coast. He was a Sergeant Major by name Samurl Q. Quartey a Royal of Jamestown, Accra. He made it home safely to Accra, Gold Coast when the war was over. He never talked about his war experiences with his children. I have been searching for any war pictures of him. I am happy to learn these brave West African heroes had a place in history after all.

Re the Biddy Jones comments of June 2021 about Frederick William Woodman my father Captain Evan Stirling RAMC did not begin his SEAC service until October 1944 – so it is possible that he had knowledge of the death of your relative, but I am sorry that I have no further details Worth commenting that despite his field hospital links with the West African troops, the MOD continues to insist he was always based in Dhond in north India, many miles from the fighting in Burma – still seems odd to me

My father served in Burna in a tank regiment. I am very upset that records of his service do not appear to exist.

He never spoke of the war with the Japanese but held a great dislike for them to the end of his life and suffered nightmares throughout his life.

If anyone can provide any insight i would be grateful. I don’t even know his regiment.

No records on when he joined or left the army. He was a trained morse operator and navigator in the tanks.

How can i pass on details to the future generations on his bravery, torment and steadfastness if i can not give tthem basic information.

Any help on how i can locate his records gratefully received. No records on Find my Past or Forces War Records online.

Thank you.

Sue

My Grand Father Sergeant Johnson Emefe Aghomi served with the 82nd Division ( West Africa Regiment- Nigeria) 1941-46 .

He saw action in Burma, he never spoke much about the war and as I recall as a child he had a cold glare most of his life and definitely suffered the effects of PTSD.

He would tell my Dad sparingly about the horrors of battle with the Japanese and the close quarter hand to hand combat he frequently had to engage in with his comrades.

I tried many years ago writing to the MOD to request military medals but was fobbed of by them to speak to the Nigerian Army.

He never fought for them he fought for Britain ! , I am still angry recalls this , is there anywhere I can receive help or be pointed in the right direction ? .

This page has given me a new zeal to see my Grand Father honoured properly and not “forgotten “ and important for my children to see his sacrifice and contribution to the World.

Thanks

Good to see the West and East African soldiers remembered.

My grandad William thomas renowden 1906-1965 was in the 14th forgotten army royal artillery he was from cornwall he was away for over 5 years ,came home with dysentery and malaria and had to be hospitalised at Netley hospital Southampton, he always suffered a bad chest after the war and died in 1965 aged 59,we have a photo of him in Burma

My Grandfather Isaac QUARTEY-PAPAFIO also served in Burma I was fortunate enough to have met him because he came home

My grandfather Sergeant Salifu from Gold Coast current day Ghana served in the Burma War under the British crown. Unfortunately, he passed away before i was born. information I got from my family was vague because proper records were not kept. Any help on how to get records about him will be highly appreciated.

Thank You.

To ALL replies;

My Grandad was a Medic and after the African Campaign he went with 81/82nd Div to Burma. As a RAMC medic 3Field Ambulance/ West Africa.

Please contact me about the Chindits/Ghurkas and Indian and British troops please

Especially all medic records I am lifelong searching.

All help most welcome.

“The day was ‘spent very quietly,’ with the African troops ‘holding a Wassa’ in the evening. ‘Wassa’ is the Hausa word for play. (Hausa is the lingua franca of the Nigerian Military, owing to the historical origins and personnel components of the Nigerian Army since its founding.) It is a celebration that includes various forms of entertainment, and the tradition is still being practiced by the Nigerian Army. The event is held annually and features various forms of military entertainment, calisthenics, and showmanship. Although some military formations in Nigeria now use ‘West African Social Activities’ (WASA) as the more anglicized and modernized version of ‘Wassa.’ Hope this helps.”

Bill

p.s. My grandfather also served in Burma, and we have lost all his military paraphernalia during the events of the Nigerian civil war and due to poor storage in humid weather conditions.

Finally after all these years, I have stumbled on what REALLY happened to 3GCR in the Arakan where my late father served as a subaltern but refused to talk about it until he died in 1986. As a youngster his behaviour in the 1950s I now recognise as classic PTSD, resulting in a persistent lifelong smoking habit that eventually killed him. In his boots I would surely have done the same.

Thank you for revealing the ugly reality of one of the dirtiest theatres of WW2. How lucky we all are that they defeated the menace.

My Dad, Ted Medhurst, was in the engineers in the 81st West African.

BURMA 1944. Can anyone help with information regarding the location of the 27th (WA) Field Dressing Station in June 1944, or indeed, anything about this particular FDS. It may have been linked in some way to the 6th Nigerian Regiment, but I’m not sure. Thank you

My Grandfather is Ashaley OKo, he fought in Burma from Ghana with two brothers. One did not make it back.

My grandfather, Joseph Garbrah, from Cape Coast, Ghana, saw action in Burma at age 24. He returned and died in the year 2000. may his soul and that of the faithful departed, rest in peace.

My granddad’s name was Onyia Nvene, he was part of the Nigerian army regiment sent to fight in the Bush war in Burma. He also fought in India. My dad said he must have been in his early 20 when he was recruited. He was awarded 3 medals from the war campaigns. He died in 1977. I never met. It’s sad that I couldn’t find any record detailing his contribution to history, and I’d very much like that.

My Nigerian grandad Joseph Imohiosen from Ora village in Benin served in the British army and was sent to Burma.He returned back to the village safe and worked as the village policeman.Another family from a nearby village with the same surname not related ,a former proffessor at Cornell had their father serve also. Therefore there must have been quite a few soldiers from this part of Nigeria.Edo ,Benin.My grandad had a framed document on his living room wall.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.