The Archivists’ Guide to Film is a blog series in which staff at The National Archives write about favourite films that have a connection to documents held in our collections. The films cover a wide range of topics and historical periods, from the Second World War to key moments in social history.

So settle in with your snack of choice and get ready to brush up on your film and history trivia knowledge. You’ll be ready when the pub quiz makes its return. (Please note that this blog contains spoilers so you may wish to read it after watching the film).

To mark Women’s History Month, the next film in our blog series is ‘Suffragette’ (2015), directed by Sarah Gavron. The film tells the story of the English suffragettes’ fight for the vote which was granted to some women over 30 in the UK in 1918. The film focuses on the suffragettes, the activists whose militant strategy aimed to disrupt society in a number of ways to prompt the government to heed their appeals. The film focuses less on the actions of the suffragists, who engaged in the women’s suffrage movement using peaceful, non-confrontational methods. Many of the film’s characters are based on, or have similar stories to, real individuals whose lives are well-documented within The National Archives.

The film is set in 1912 in London. Carey Mulligan plays Maud Watts, a young wife and mother of one who is employed as a laundry worker at the Glasshouse Laundry in Bethnal Green. The conditions of the laundry are extremely poor, and it is implied that its employees are suffering physically and mentally as a result.

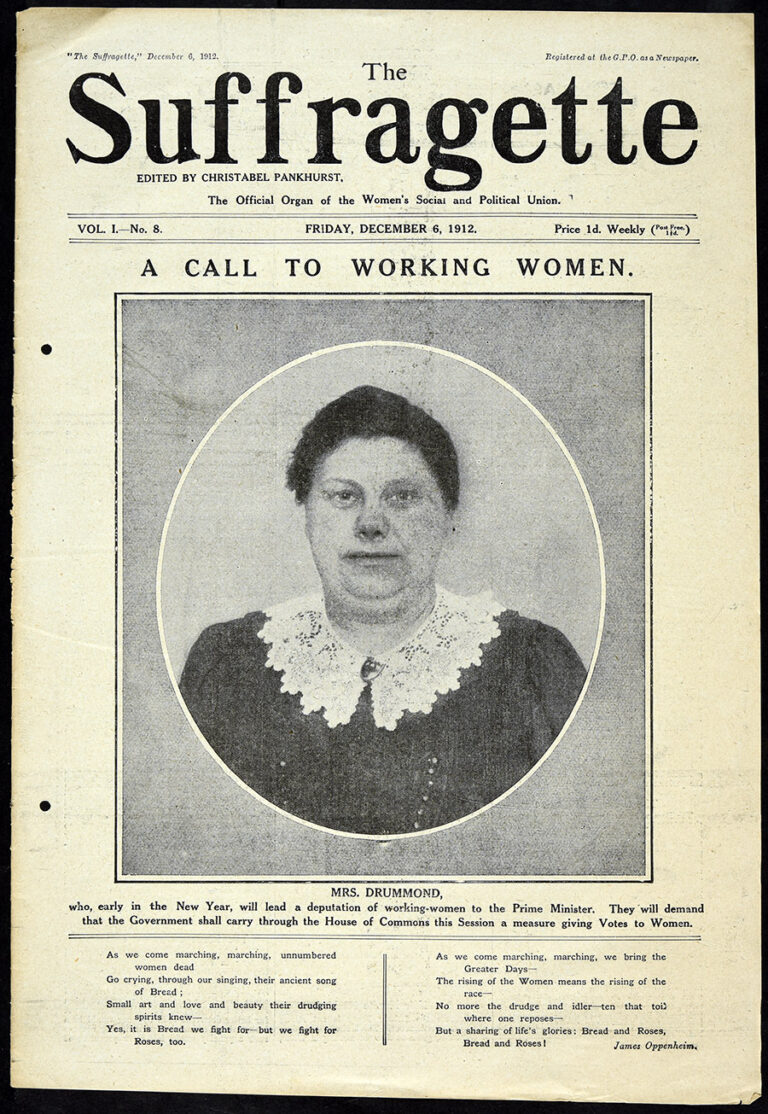

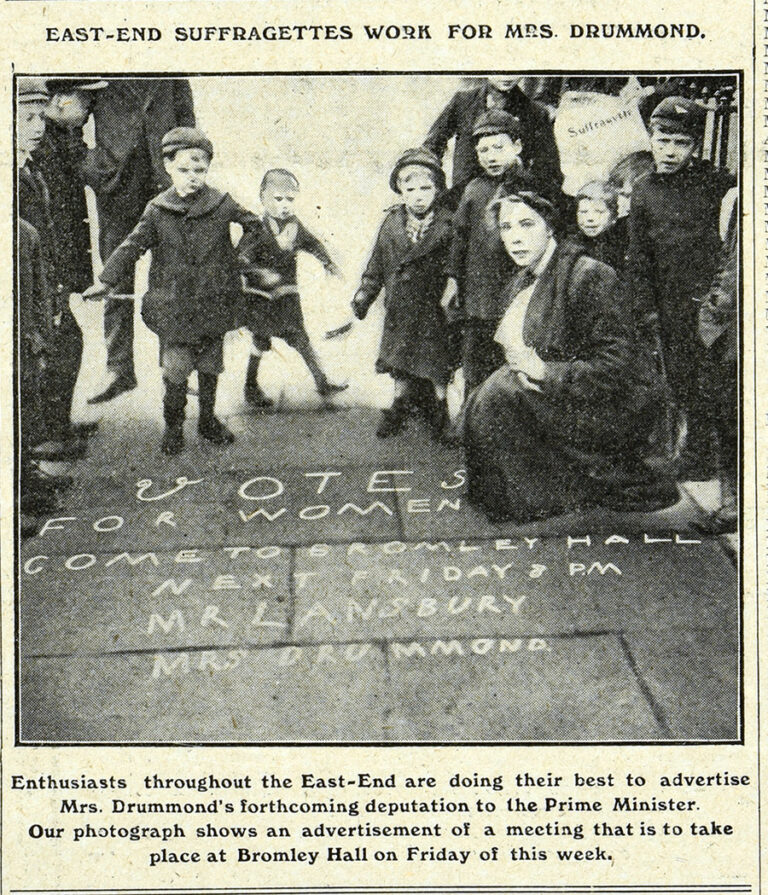

Out in the street one day, Maud witnesses a suffragette protest involving her fellow laundry worker, who later encourages her to make a deputation in Parliament about getting the vote and the impact it would have on women’s lives. This scene makes reference to real events, as in 1913 The Suffragette newspaper called for working women across England to be part of a deputation to the Treasury. You can learn more about the deputation in this blog post.

Maud describes her work and living conditions as a laundry worker, while a group of other women labourers wait their turn to speak. After learning that the vote hasn’t been extended, Maud and a group of other suffragettes protest in the street, leading to a violent response from the police towards the women, and then to their arrest and imprisonment.

This scene seems to be based on the events of Black Friday. On 18 November 1910, 300 women, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, gathered at Parliament to protest Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s decision not to allow any more time on a bill to give approximately one million women the vote. This escalated into violence, and approximately 200 women were injured or sexually assaulted by police. You can learn more about Black Friday in this blog post.

The brutal treatment of the suffragettes by police and men abusing positions of authority features throughout the film, from Maud’s abusive manager at the laundry, to the policemen she encounters throughout the film, to her husband’s oppressive and controlling behaviour. The film’s male characters range from highly oppressive (such as Maud’s abusive manager in the factory, who exploits and degrades his workers) to Maud’s husband Sonny, who, accusing her of being mentally unstable, refuses to let her see her son and later gives him up for adoption without her consent.

Men who supported the women’s suffrage movement are also represented in the film, such as the character Edith Ellyn’s husband, who helps his wife and the group to covertly assemble explosives used on pillar boxes.

Maud’s story is very similar to that of a real-life suffragette named Lillian Ball, who was arrested for smashing windows as a form of militant campaign in 1912. Similar to Maud’s character, Ball was told by the police that if she wanted to see her son again, and serve a less serious sentence, she could do so by giving them information about the Pankhursts in court. You can read her statement here.

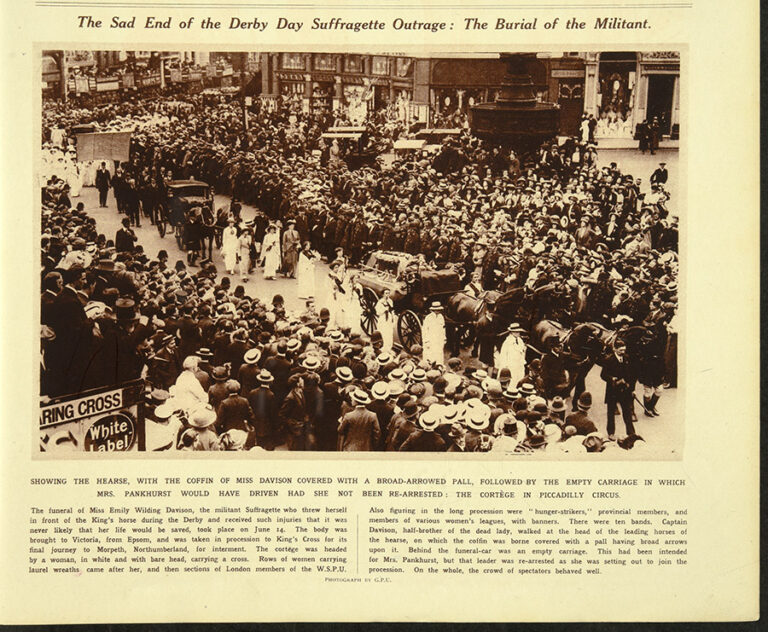

After their political tactics escalate and become more and more disruptive, the film culminates with Maud and Emily Wilding Davison attending the Derby in the hope of unfurling their suffragette flags to attract the attention of King George V, who is in attendance. When their attempts are unsuccessful, Emily walks on to the track and is trampled to death by the horses.

The National Archives holds several records relating to Emily Davison’s life and death, and whose life and activism has been a source of much discussion, for example in blog posts such as this one.

Davison was deeply involved in the movement and performed many brave and daring militant tactics in order to progress the fight for women’s suffrage. In one record, film footage from British Pathe shows from a distance Wilding being trampled by the horse at the Derby, with the title card saying ‘Suffragette killed in attempt to pull down the King’s horse’. The footage is bleak and difficult to watch, but shows how Davison’s death was difficult to determine as either an accident, a suicide or a failed attempt to promote their cause.

‘Suffragette’ ends with Wilding Davison’s funeral, depicting thousands of suffragettes marching in honour of her life and the continued fight for suffrage. Her funeral was organised by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

The influence of class and wealth on women’s level of power, freedom and agency during this historical period is explored in various scenes in the film. When Maud is imprisoned and needs money for bail, one of the upper-class suffragettes asks her husband for bail money for all of the suffragettes who have been locked up, and is turned down.

It is evident that Maud is risking more than her life for her cause, as protesting means losing the financial support of her employer and, without any legal rights over her son, custody and her home.

The film shows that the suffragettes’ political and militant actions were effective in their aim of making newspaper headlines, but the film suggests that perhaps just as important were the small acts of resilience that changed the course of their lives, such as quitting their arduous jobs or assisting one other financially. In one scene, Maud swiftly extricates one girl from the laundry who she knows is being abused, and brings her to the home of a wealthy suffragette to work, demonstrating how such a small shift from working in a factory to an upper-class home could make a huge difference in this woman’s life.

While the film gives a generalised overview of a complex political movement, its brilliant actors portray many of the struggles faced by these women and their loved ones, shedding light on their perseverance and the sacrifices they made to achieve their aims. The film and the records we hold are humbling reminders of the huge efforts that lead to incremental societal changes.

Women have been around since the beginning.

Why didn’t they have the vote then?

Women’s activities in local government and school boards from the late 19th century could be referenced (Emma Cons and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson are notable – and eg the Women’s Local Government Society).

keep telling the stories, particularly to school children/ students.

needless to say they keep alive the sacrifices of the women and informs the younger generations how other women fought for the positions women are holding nowadays.

If any causal factor ‘changed history’ what was it changed from? Or do those using the expression subscribe to the concept of predestination? In their insistence that ‘history’ is the record of the past, postmodernists were simply stating the obvious disguised in their obfuscatory language,but as in Orwell’s novel, the record of the past is subject to alteration. So did the suffragettes have access to the records, enabling them to ‘change history’?

Paul, I doubt the men who kept parliamentary or any other records would have indicted themselves by including predatory suffering upon working women in their record keeping…are you saying that because you are unable to find a record detailing the suffering of working women that their suffering did not exist? Simply seeking clarification here…I have a brother who like makes use of obfuscatory language to bluster his way aimlessly and thoughtlessly through discussions about women’s suffrage…other wise I fail to see the purpose of your comment.