James Pennethorne (1801-1871), 19th-century English classical architect, was born on 4 June 1801 in Worcester. He was heavily involved with the wider mid-19th century development of the London metropolis. Yet many of his plans were unrealised and his major projects were hindered by financial difficulties, lack of support through government policy, and competition with other architects and styles.

Pennethorne was a second cousin of the wife of eminent Regency architect John Nash (1752-1835), and trained with Nash in his office in London during the development of Regent’s Park and the surrounding areas. His first professional position was as Nash’s principal assistant and he worked on projects including the Strand Improvements, Carlton House Terrace and St James’s Park.

He was first employed by the Office of Woods and Forests in 1832, as ‘an independent professional man’, and later appointed joint architect and surveyor for the Metropolitan Improvements with Thomas Chawner (1774-1851) in 1839, beginning a long career of public service that culminated in a knighthood granted shortly before his death in 1871 1.

Pennethorne was in effect the government architect for Victorian London which is why we hold many of his drawings and plans for buildings, parks and street improvements at The National Archives, both realised and unrealised. These refer to a wide range of 19th-century Metropolitan Improvements and public buildings, including, among many others, the west wing of Somerset House, Victoria Park in East London and the creation of four new streets in central London, including New Oxford Street.

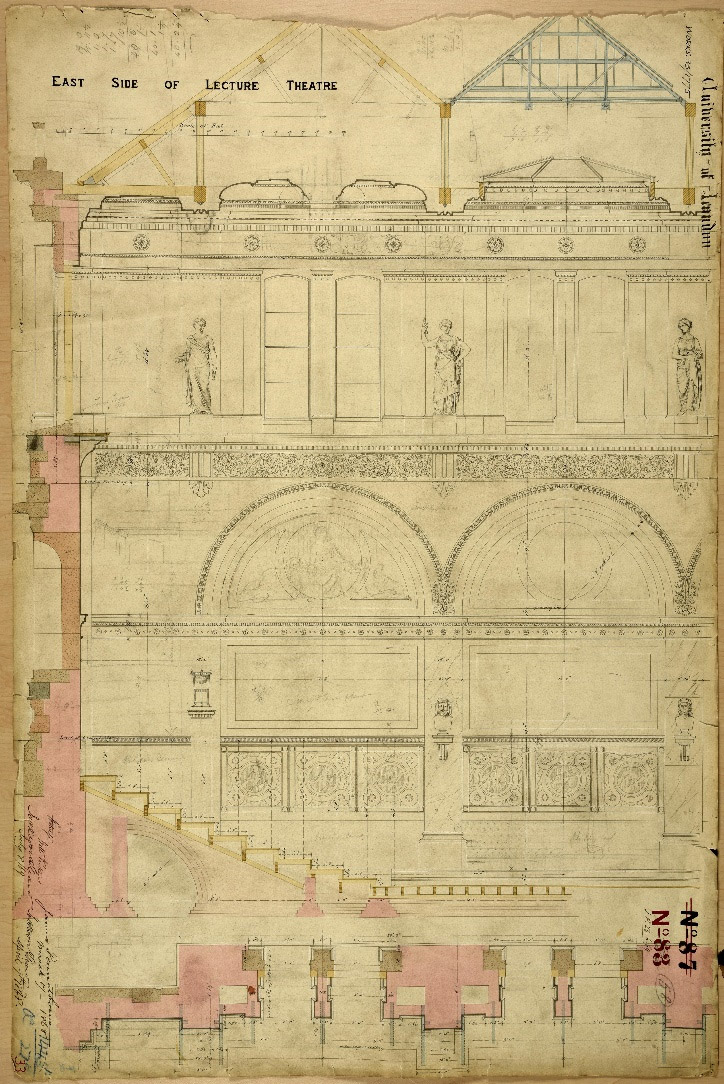

There are also plans for Royal residences, including extensions to Buckingham Palace and the Duchy of Cornwall offices, and 6 Burlington Gardens developed to house the University of London. This in addition to a range of correspondence and reports relating to works planned and carried out as well as Pennethorne’s employment.

To quote from Pennethorne’s obituary read at a meeting of the Royal Institute of British Architects on 18 December 1871: ‘any memoir of Sir James Pennethorne, which would pretend to do justice to his labours, would in fact be a history of almost all that has been done or projected for the improvement of the metropolis within that period’. 2

This is certainly beyond the scope of this blog post, so I have decided to look at a few select records we hold for a Pennethorne building readers of this blog are likely to be familiar with, the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane.

Pennethorne and the Public Record Office

By 1800, a crisis in records keeping and storage had been recognised in England. A Select Committee was set up by Parliament to assess the state of public records which were housed in multiple locations across the country and under varying conditions (in extreme cases, with starving rats). However, not until 1838 was the Public Record Office Act passed, placing records under the keepership of the Master of the Rolls, the official in charge of the records of Chancery, and recommending that a dedicated Public Record Office be built which the Treasury was tasked with finding.

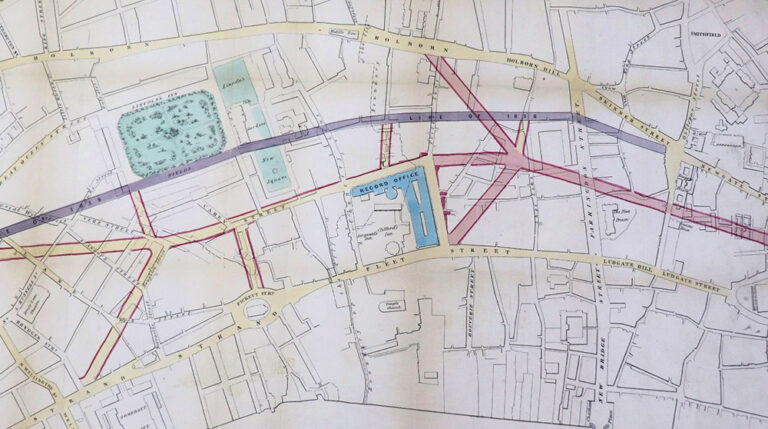

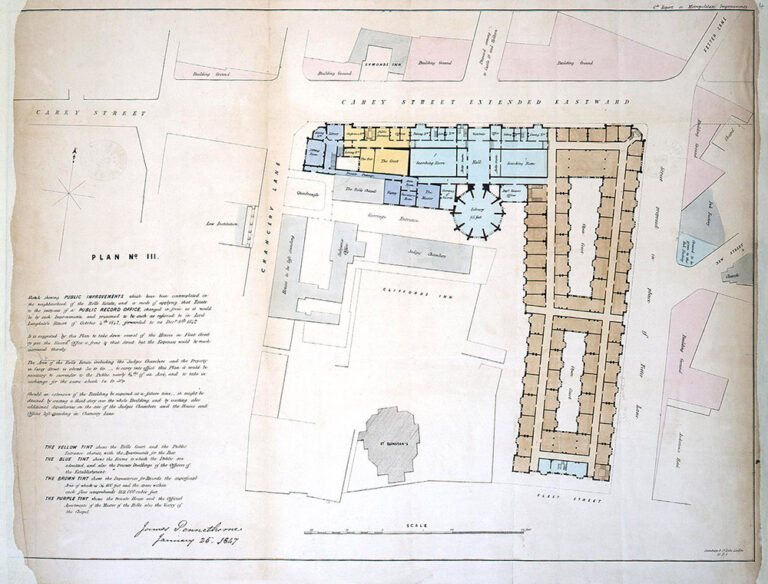

The site for the building was to be the Rolls Estate, between Chancery Lane and Fetter Lane, chosen for its proximity to the law courts.

Meanwhile, James Pennethorne had drawn up plans for a ‘Great Central Thoroughfare’, a street that connected the East and West of the city, intended to bring some order to the chaotic layout of London and break up overcrowded slums. The plans for the thoroughfare were relocated to pass the northern edge of the Rolls Estate and Pennethorne also put forward the first of his plans for a General Records Repository 3.

These plans show a much larger building than the one finally accepted, with the brown tinted areas of the plan representing 810,000 cubic feet designated for depositories of records on each floor, two large searching rooms and a library 65 feet wide, all to be built in an Elizabethan style.

However, these plans were rejected for being too costly and new set of criteria was laid out that involved reducing both storage space and facilities for the public was set out by Francis Palgrave, the Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office 4.

Pennethorne submitted a report that included his observations on the modes of storage of other ‘libraries and depositories of most of the public establishments in London’ 5. Among those listed in the report were the British Museum, the State Paper Office, the Bank of England, the Custom House, the India Office and the Admiralty. At the Audit Office in Somerset House, for example, Pennethorne describes that ‘the papers are deposited in a long gallery in the first basement, in wooden cases on each side and warmed by a stove’, or at the Bank of England: ‘There is no precaution against fire, but lights are never permitted; no accident has ever occurred’ 6.

The references to heating methods were important on two counts. Palgrave submits a section in the report with a description of the historic storage of Domesday: ‘the earliest English Record is deposited in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey, in the vaulted porch, never warmed by fire. From the first deposit of Domesday volume in the Treasury at Winchester in the reign of the Conqueror, it certainly never felt or saw a fire: yet every page of the vellum is bright, sound and perfect.’ 7

Palgrave argued that artificial heating was unnecessary and its effects damaging to both the records and staff; yet the building also needed to be fire proof. Open fires were chosen as the preferred method over a central heating system using water or stoves due to concerns the latter would mean less ventilation and a suboptimal climate for paper records. At the same time, the choices of building materials reduced the risk of combustion; stone and brick were chosen, with strong rooms made with iron and slate shelving. 8 Stone was quarried from Anston, Portland and Mansfield.

The new plans submitted by Pennethorne in the summer of 1850 show a Gothic exterior and an imposing clock tower over the main entrance to the building, which was later adapted when the tower was finally built in 1865-7. The tower that stands today has four corner turrets and lower turrets containing four statues depicting queens of England 9.

Dubbed the ‘strong box of the Empire’, the imposing style of the building was very much in the spirit of ‘form follows function’.

The first stone was laid by the Right Honourable Sir John Romilly, Master of the Rolls and Keeper of the Records ‘at 25 minutes before 2, on Saturday afternoon, 24th May 1851’, which is also noted in the record of the event as being Queen Victoria’s birthday 10. However, as a result of indecisions during construction and delays to supplies, building work progressed slowly – the Public Record Office did not open until 1859.

When it did, it was not well-received and there were complaints of the darkness and the damp, ironically contrasting with the original intentions to protect against fire and heat. The cramped conditions and, possibly worst of all, the fact that it was unfit for purpose, being already unable to accommodate the storage of more records, were also noted.

Already by the 1860s an extension was required, designed by Pennethorne and built between 1863 and 1868. The extension now incorporated two reading rooms, including the famous Round Room built in glass and iron. It also overrode the original stipulation of open fireplaces; it had central heating via water pipes, with the water tank built into the tower 11.

That Pennethorne foresaw these issues is indicated in a handwritten note, made out on 4 May 1863 to the Deputy Keeper of the PRO, Thomas Duffus Hardy:

‘My dear Sir

Some day we shall all of us be dead and gone – and fifty years hence the memory of us maybe [sic] kept alive if in your Record Office should be found my first original sketch for the new office made with my own hands – will you do me the favour to accept it and put it away with other rubbish.

You will see that in those days we saw the necessity for a large library, for large searching rooms, for the maintenance of the Rolls Chapel, and of the Court, a House for the Master, for the Deputy Keeper, etc. etc.

All these things were washed away by economy and will hereafter have to be provided at greater cost and with less convenience.

Ever yours faithfully,

James Pennethorne’ 12

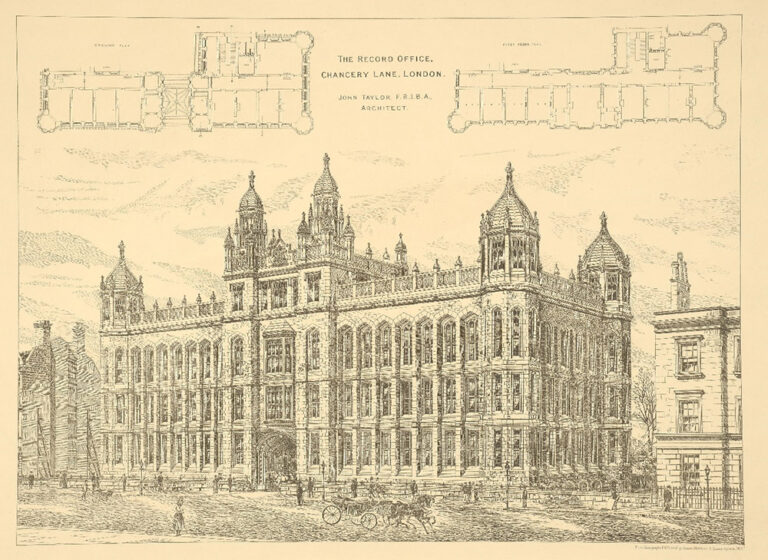

The northern section of the East Wing was completed in 1870. Pennethorne drew up plans for the remaining sections of the building but he would not see these built during his lifetime. Later extensions were carried out by John Taylor (1833-1912) between 1891 and 1896, when storage space again ran low. These largely followed Pennethorne’s designs with some adjustments made by Taylor.

Conclusion

Again, it was the serious requirement for more space, particularly for larger reading rooms, that led to the search for a new site for the Public Record Office in the 1960s and the eventual building at Kew being designed by John Cecil Clavering of the Property Services Agency.

After the new building’s construction and the relocation of records was completed, the Chancery Lane building was acquired by King’s College London in 1998. Its interior was renovated and today it functions as the university’s Maughan Library.

I believe one of the key interests in Pennethorne’s designs are the fascinating glimpses they give into the plans for Victorian London that were never realised but could have been – and there are many plans and drawings at The National Archives still to explore which satisfy that.

For a comprehensive history of Pennethorne’s contributions to architecture, there is no study better than Geoffrey Tyack’s Sir James Pennethorne and the Making of Victorian London (1992).

Notes:

- T 1/6693A Paper numbers 3774-3887 (1867). ↩

- PRO 8/17 ‘A Biographical Notice of the late Sir James Pennethorne’, a paper read at an Ordinary General Meeting of the Royal Institute of British Architects held on 18 Dec. 1871. ↩

- Geoffrey Tyack, Sir James Pennethorne and the Making of Modern London, (1992), p.148. ↩

- Tyack p.150. ↩

- T 1 5565B/14. ↩

- T 1 5565B/16. ↩

- T 1 5565B/33. ↩

- A history of the Public Record Office. ↩

- A history of the Public Record Office. ↩

- PRO 8/4 Public Record Repository. Plans and papers relating to the building of the first (centre) Block (1845-1863). ↩

- Tyack, p.158. ↩

- PRO 8/4. ↩

There were no set public right of access to the records until 1958, some departments allowed access but at a cost. The need for large reading rooms came from the introduction of the photocopier in Government departments and even then it took 14 years to build the original TNA building at Kew, now known as Kew 1. Terrible to store records in wooden stacks, we are lucky that the Suffragettes didn’t attack it unlike other buildings!.

As a member of the unit planning the and implementing the move of 48 miles of records to Kew 1 (Fort Ruskin) working in H 19 and Hanover Sq was an interesting (and enjoyable) experience thanks to the team leaders “Jimmy” (L.G.) Seed and Lionel Bell.

As a member of the unit planning the and implementing the move of 48 miles of records to Kew 1 (Fort Ruskin) working in H 19 and Hanover Sq was an interesting (and enjoyable) experience thanks to the team leaders “Jimmy” (L.G.) Seed and Lionel Bell.

The racking at Ashridge was (possibly) wooden but at Kew it was high quality steel.

The racking at Ashridge was (possibly) wooden but at Kew it was high quality steel.

DM, just reread your comment. 14 years to build Fort Ruskin! Who told you this? They started digging the hole for the foundation structure in 1973/4 and started moving records into the building in 1977. I have a photograph of the four of us standing on the over site surface. At the time RPU comprised Lionel Bell, Jimmy (LG) Seed, Nigel Kent and myself.

Did Pennethorne design the buildings in West Central Street Camden? No. 16A is currently threatened with demolition. Be grateful for reply thank you