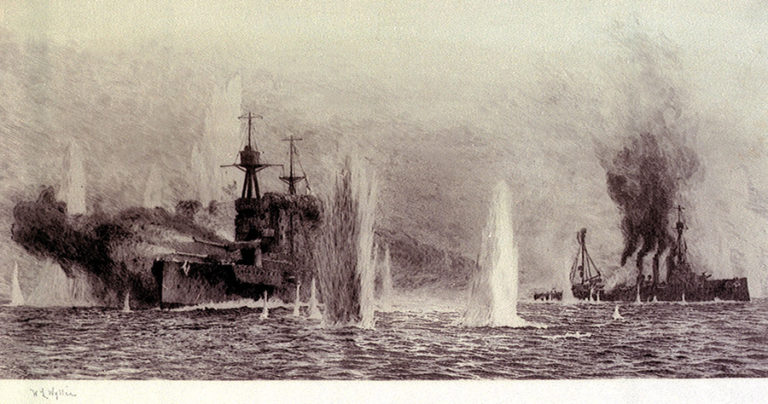

When I think of war at sea, my mind turns to images of Trafalgar or Jutland. Big battleships bristling with guns, slogging it out in a duel, trying to blast each other out of existence and send the remains to Davy Jones’s Locker.

But those set-piece battles of annihilation were the exception, not the rule. The bread-and-butter business of maritime conflict has always been war on (or to put it another way, enforced regulation of) trade: pressure applied over long periods directed at disrupting the seaborne commerce of the enemy, with the object of depriving them of the wherewithal – financial and material – with which to prosecute the war.

Even now, I’m still picturing packs of U-boats loosing off torpedoes against merchant ships in the North Atlantic, or Admiral Hipper running amok among convoy SLS 64, sinking seven out of 19 with direct hits from her great guns.

That wasn’t always the way. The practice of sinking merchant ships was really only a 20th-century aberration in the long history of war on trade, and came about as a peripheral consequence of technological developments in ships and guns: once fitted with 12- or 15-inch guns firing high-explosive shells 10 or 15 miles with some accuracy, it became much easier and quicker, and far less risky to her own safety and that of her crew, for a warship to stand off and lob a shell into the boiler of a steam ship constructed from thin riveted steel plates, blowing the whole vessel apart, than it would have been to chase her and try to board her.

And once the sneaky submarine made her appearance (or didn’t) on (or under) the scene – well, the whole point of being a submarine is that you stay as long as possible safely concealed beneath the friendly waves, from which location you really only have two options: sink the enemy, or let her go on her way. (I know, purists will be shouting that U-Boats did on occasion make surface attacks using their gun. But by doing so they were vulnerable to air or sea attack, and even to their intended victim fighting back. And how often did a submarine capture a ship, put a prize crew aboard, and sail her to port?).

In the Age of Sail, actually sinking a naturally buoyant wooden ship by firing relatively small, low-velocity iron balls at her required a dedication to purpose, not to mention large supplies of gunpowder and shot and probably the better part of a day to devote to the project.

And what would have been the point? Rather than blow the ship apart or set her alight and drown the crew, surely the clever strategy was to put the wind up enough of the crew to persuade them that the better part of valour was surrender? That way, not only did the victors achieve the strategic object of depriving the enemy of the ship and her cargo, but they gained those things for themselves, rather than letting them rot on the ocean floor where they would do nobody any good, except for a few fishes and a family of barnacles.

So, for most of Mankind’s long and noble history, war at sea was mostly about capturing merchant ships, not sinking them, and not about the big, glorious, usually strategically indecisive battles the history books are full of. (Plenty of these are available in our bookshop).

People at the time were well aware of this Fact of Life. Some may have run away to sea in the hope of covering themselves in glory. In Europe’s ‘Romantic Age’ ideas of glory often linked heroism and riches, which brings us to the grubby subject closest to the heart of every sentient seafarer: Money, with a capital Mmm.

In the Age of Sail, a considerable number of sailors got rich by capturing ships, and not a few landlubbers, especially of the banker and merchant varieties, got even richer. Many others dreamed of such riches. More about the financial allure of a life on the ocean wave in my next blog, but let’s examine here the legal underpinnings.

To enthuse naval crews with the virtues of the war against commerce, the law granted to the captors the proceeds of the sale of captured ships and cargoes. This prize money was shared out between all the men, from captain to cabin-boy, and many a young officer dreamed of getting command of a swift frigate and a commission to go cruising in search of prizes.

But the navy were busy with various strategic operations in wartime, like deterring invasions, and mounting invasions of their own; and so to supplement the forces available to wage war on the enemy’s commerce, private enterprise was encouraged. In the many wars of the long 18th century, private warships, licensed by the State but owned and equipped by businessmen and bankers, patrolled the seas on the lookout for enemy merchantmen sitting low in the water.

It is important to understand we are not talking about piracy, here. Pirates and privateers are often lumped together in the popular imagination (and by some scholars who ought to know better) but they were fundamentally different beasts: pirates were sea-robbers, outlaws, the maritime cousins of highwaymen and cutpurses. Privateers operated within a strict legal framework which began with registering their ship with the Admiralty and standing £1500 security for the commander’s strict observance of the rules. In exchange, a letter of marque or commission was issued, which authorised them to ‘take and seize’ vessels and cargoes belonging to certain specified (enemy) states.

Even when Britain was at war with several countries at once (pretty much the norm in the 18th century) a separate letter of marque was generally required to attack each enemy. When the court found, as it not infrequently did, that what had been taken did not belong to Britain’s enemies, or that some legal nicety had not been observed, the ship or cargo had to be restored to its rightful owners or (if it had been sold or damaged) compensation paid them.

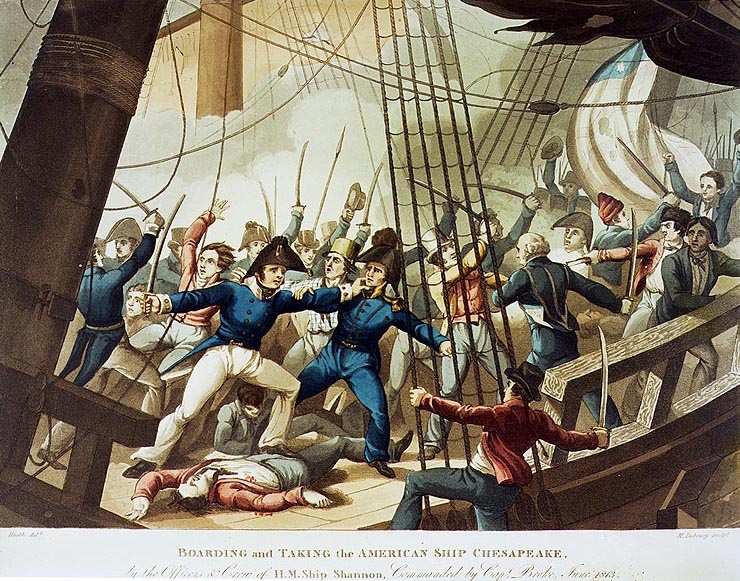

When a suspected enemy ship was sighted (by a privateer, or by a naval vessel – the same rules applied to both, and both were entitled to prize money) the would-be captor would signal for the ship to heave to and allow a boarding party aboard to inspect their paperwork. If they had nothing to hide, because for example they were carrying only cargo belonging to neutrals or allies, they would comply, and after perusing the bills of lading and the ship’s log, the would-be captors would let them go on their way. (To seize a ship which would subsequently have to be restored with compensation and legal costs would be a major financial loss and therefore something to be avoided).

Sensible merchant captains who were carrying enemy or contraband goods and found themselves challenged by a warship of obviously superior force would also surrender without a fight; but others, fancying their chances of out-running or out-gunning their opponents, might crowd on sail and make for the horizon, or put up a fight.

Whether taken peacefully or by force, once a ship was boarded and seized, there were procedures and protocols to be followed. The captain and some or all of the crew were taken off and held prisoner in the captors’ ship, while a skeleton prize crew were put aboard to sail their prize to a friendly (usually British) port. All the papers on board the prize were also collected up and closely guarded by the captors.

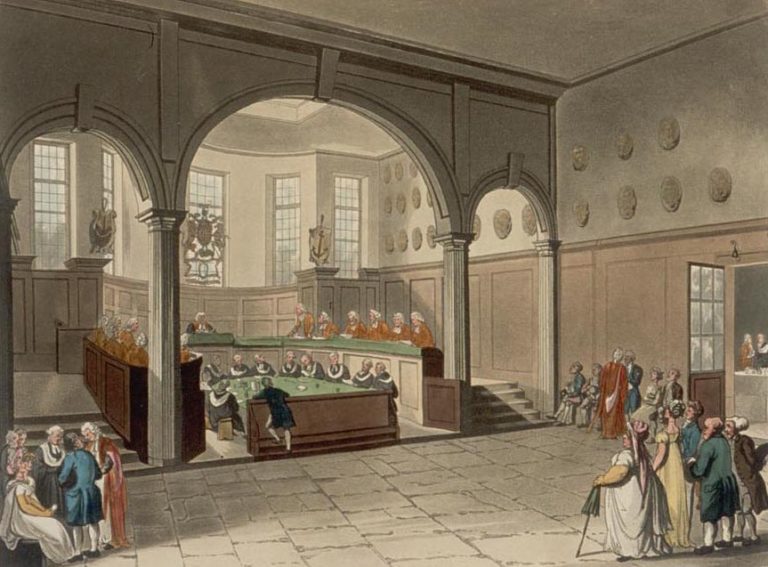

When they reached port, a selection of the officers and men of the prize would be interrogated by local officials (‘commissioners’) appointed for that purpose, who noted down their answers to certain standard questions (via interpreters, if needed) designed to get at the truth about certain crucial matters, such as who really owned the ship and cargo and what was their nationality, where the ship was sailing from and where to, etc.

The answers to these questions, along with the papers taken from the ship, were bundled up and sent to the High Court of Admiralty in London. There, the court weighed the testimony of the crew against the evidence of the ship’s papers and any claims from merchants to be the rightful owners of the ship or any part of the cargo. If the court found it was lawful prize, then it was sold and the proceeds – minus legal costs and various other expenses – divided among the captors.

Just how much money was made from prizes? That’s a good question for research, which might involve working out the total number of ships captured, the ratio of condemnations to restorations, and the average prize pay-out. In the Prize Papers at The National Archives, we have records of about 30,000 ships seized and brought to England between 1650 and 1815, but an additional uncalculated number were taken into ports in North America, the West Indies, the East Indies and the Mediterranean. And all the other maritime powers – the French, Dutch, Spanish et al – were playing the same game, following broadly similar rules, and amassing fortunes for themselves.

All work for the future.

Comments are temporarily closed