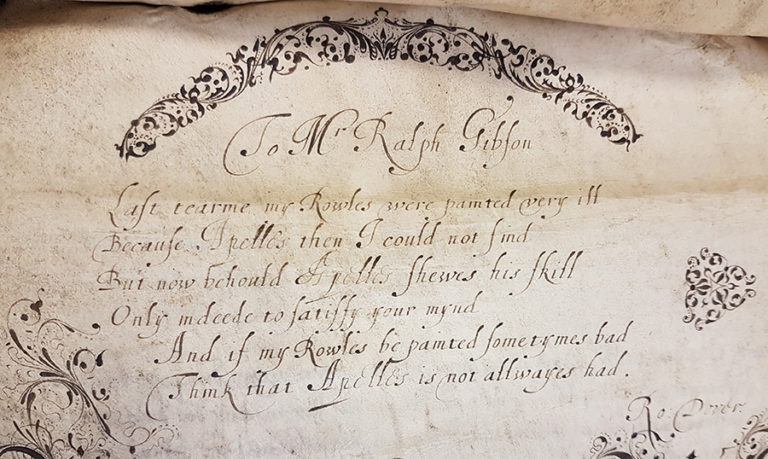

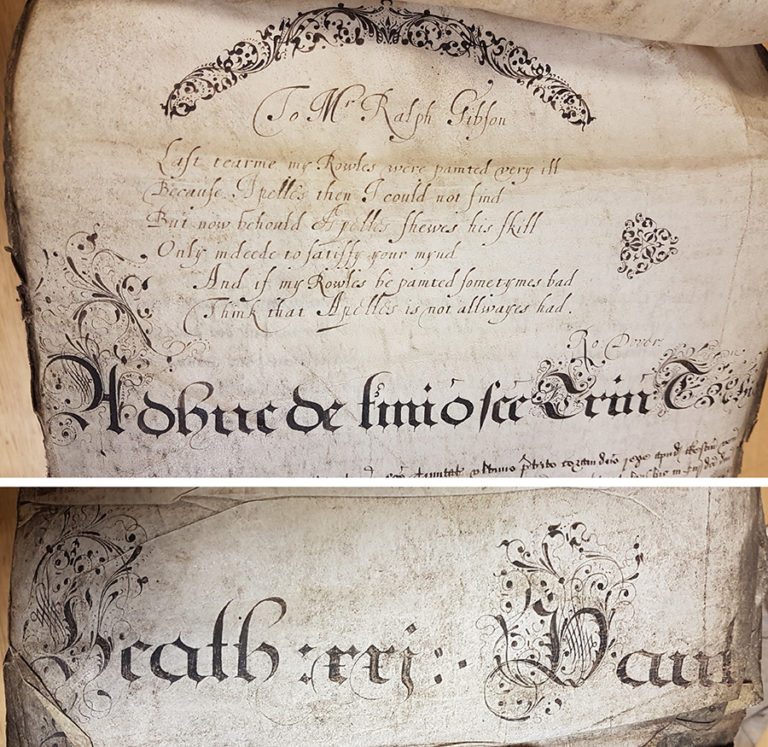

“To Mr Ralph Gibson

Last tearme my Rowles were painted very ill,

Because Apelles then I could not find,

But now behould As pelles shewes his skill,

Only indeede to satisfy your mynd,

And if my Rowles be painted sometymes bad,

Think that Apelles is not allwayes had.

Ro. Dover” 1

It isn’t often that we find poetry hidden within the legal records that form a large proportion of the pre-modern collections at The National Archives, and even less common to find a previously unstudied work from a known poet which describes the production of the same rolls. Hidden away in the King’s Bench plea roll for Trinity term 1627, however, is one such poem: a short piece written by Robert Dover, a figure who moved in the leading literary circles of the day and who also acted as an attorney within the same court.

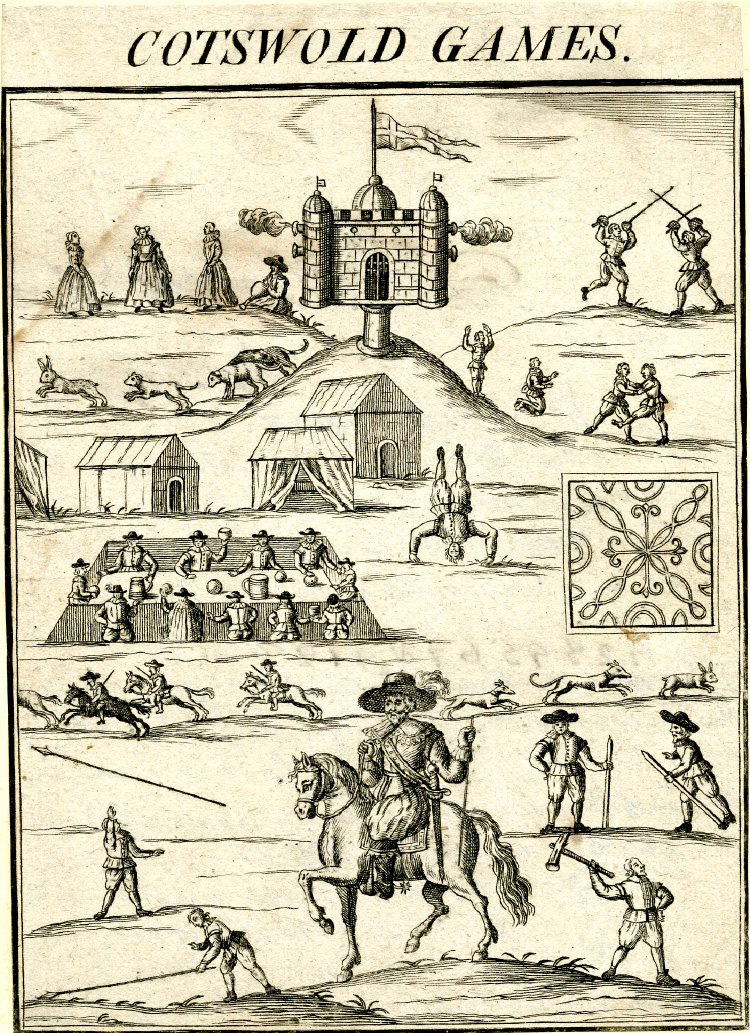

Dover was a Cotswolds lawyer who had trained at Gray’s Inn and worked as an attorney for those in the Cotswolds or the Vale of Evesham during the first decades of the 17th-century 2. Renowned as being fair in his legal dealings – settling matters out of court wherever possible – as well as generous, jovial and noble minded – Dover is perhaps best-known for his organisation from 1612 of an annual Whitsun sporting competition in the Cotswolds, which would become known as ‘Mr. Robert Dover’s Olimpick games upon the Cotswold Hills’, and which continues in to the present day 3. Featuring sports and activities including horse racing, wrestling, jumping, tumbling (and in the modern day shin-kicking and ‘King of the Hill’), the festivities also saw a castle constructed on the hillside for the duration of the games, and much feasting and merriment.

It has been suggested that Shakespeare may have attended the games (and made reference to the festivities in some of his work), but more tangible evidence of Dover’s connections and friendships within the literary and courtly circles of early modern England are clear from the account of his games – Annalia Dubrensia – published in January 1636, which contains 33 poems in his honour from poets including Ben Jonson and Michael Drayton 4. Prince Rupert may have attended in 1636, while royal courtier and diplomat Endymion Porter is known to have supplied clothes for the games. Dover himself was featured on the frontispiece of Annalia Dubrensia as master of ceremonies, with the games taking place behind him, and wrote his own poem in response to the 33, one of few poems definitively attributed to him.

“An epigram to my Iovial good freind Mr Robert Dover, on his great Instauration of his Hunting, and Dauncing At Cotswold.

I cannot bring my Muse to dropp Vies

Twixt Cotswold and the Olumpicke exercise:

But I can tell thee Dover, how thy Games

Renew the Glories of our blessed Ieames;

How they doe keep alive his memorie;

With the Glad Countrey and Posteritie:

How they advance, true Love, and neighbourhood,

And doe both Church, and Common-wealth the good,

In spite of Hipocrite, who are the worst

Of Subjects; Let such envie, till they burst.

Ben Iohnson” 5

Dover’s short poem in the plea roll for Trinity 1627 gives us a very different insight into his daily life as an attorney, outside of the festivities of the Olimpicks and his courtly and literary connections. We know very little about the actual production of these rolls in the medieval and early modern period, beyond some clues we can pull out of the extant documentation for the working offices of lawyers and court officials, but this poem sheds a little bit of light on the situation.

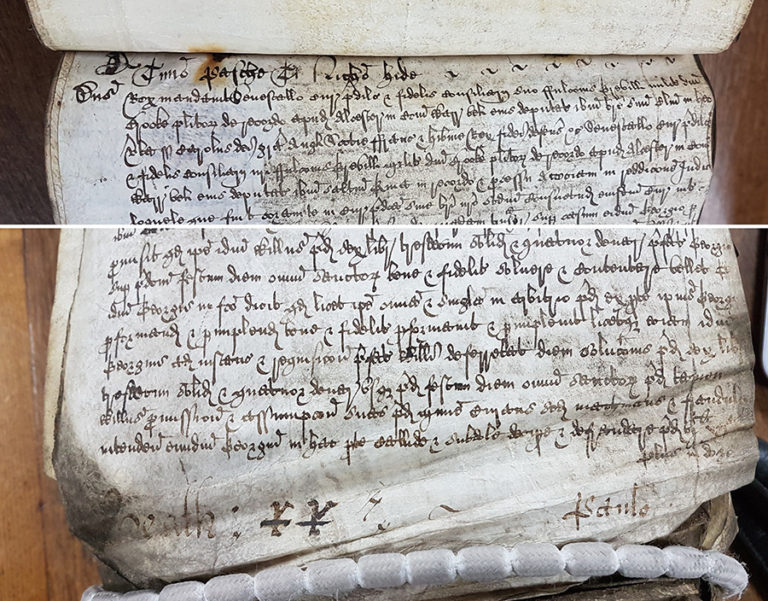

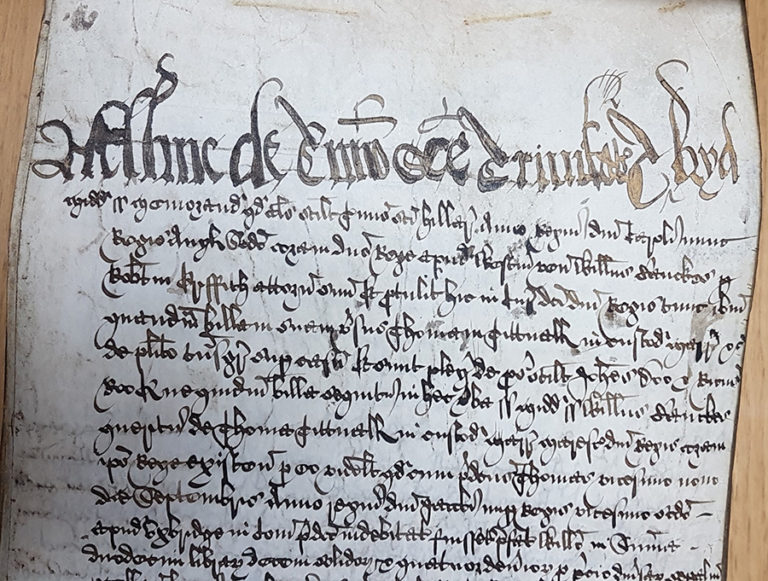

By the first decades of the 17th century, much of the actual writing of the rolls appears to have been undertaken by attorneys – acting as clerks of the court – under the supervision of a prothonotary (a chief clerk of the court), whose names were painted at the bottom of each rotulet 6 to signify their supervision of the contents 7. In earlier periods, this had been undertaken by (often anonymous) court clerks, but the regular presence of attorneys in court, alongside the privilege of King’s bench prothonotaries to control the appointment of attorneys within their court, led to a significant overlap between the two roles and allowed these attorney-clerks to supplement their income accordingly 8.

Dover, addressing his poem to an (as yet unidentified) Mr Ralph Gibson – presumably another individual involved in the production of the termly rolls – apologises for his rolls in the previous term, which were apparently ‘painted very ill’, because of a lack of (gall) apples with which to make his ink. Playing with the word ‘apples’, he goes on to state that his ‘painting’ this term is much better, ‘as pells (a term for parchment skins) shows his skill’, while preserving himself against future shortages ‘if my rolls be painted sometimes bad, think that apples is not always had’.

The problem of ink without enough gall is one that comes out in other literary sources from the period. Shakespeare in Twelfth Night (act III, scene 2), for example, writes of the problem…

‘Let there be gall enough in thy ink, though thou write with a goose pen, no matter: about it’

… while many households and writers would have produced their own inks using varying quantities (and qualities) of gall apple.

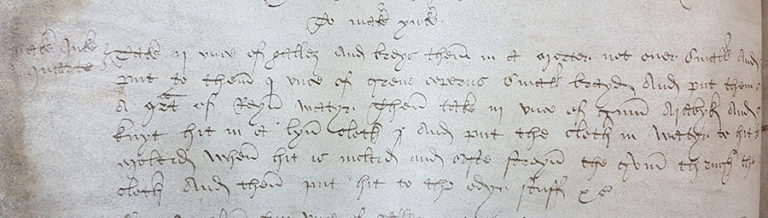

Identifying the scribes of individual rotulets (in the absence of a signed poem), can be a difficult process, and requires a lot of detective work. There are a few clues that can help us, however. Immediately under Dover’s poem, the first case recorded includes him acting as attorney, and at the end of each plea roll we often find lists of cases grouped under names of attorneys, often also relating to county groupings. The court’s own documents, which trace the progress of cases, also often note the presence of attorneys and clerks, which can lead us to the relevant sections of the roll.

Having identified the likely entries written by Dover in the previous term (Easter term 1627), his apology seems somewhat unnecessary, particularly in relation to some of the efforts of his contemporaries 9. The only notable difference in his gall-less entries is that the head and foot of each rotulet is written in a thin hand – rather than the thick and bold headings that are usual for these records – as he recorded the relevant information but without exaggeration. They were clearly not up to his own high standards as demonstrated in the roll which bears his poem.

Other groups of rotulets from the Trinity 1627 roll are considerably more imperfect, with wonky headings and empty rotulets (sometimes bearing the Latin phrase ‘nihil hic’ – ‘nothing here’ – the early modern equivalent of ‘this page intentionally left blank’), so Dover may have been expressing his perfectionism, or merely taking the opportunity to pen a short humorous poem for his superiors.

This is in stark comparison to many of his predecessors who compiled the rolls, whose doodles and sketches generally demonstrate their lack of respect, such as the scribe who described his master as ‘old shrew’, or the 13th-century clerk who (favourably) compared his genitalia to his master’s in a marginal note and doodle.

Dover’s poem, preserved in the records of the central law courts for posterity, draws attention to an imperfection that would never otherwise have been noticeable, but was clearly a concern for himself, and perhaps his superior. He was to continue in his position for some years after this event, so he was presumably successful in appeasing his superiors with his wit and verse, giving those of us with occasionally sloppy handwriting an excuse for the future!

Notes:

-

‘Last term my rolls were painted very ill,

Because apples then I could not find,

But now, behold as pells shows his skill,

Only indeed to satisfy your mind,

And if my rolls be painted sometimes bad,

Think that apples is not always had’: TNA, KB 27/1555/1, rot 21 (Trinity 1627). ↩ - F D A Burns, “Dover, Robert (1581/2–1652), organizer of the Cotswold Olimpick games.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. September 01, 2017. Oxford University Press. Date of access 31 Mar. 2020. ↩

- https://www.olimpickgames.co.uk/ The games were not held between 1852 and 1951, when they were revived for the Festival of Britain. ↩

- A free pdf download of the Annalia Dubrensia can be found here. ↩

- Annalia Dubrensia. ↩

- ‘Small rolls’, or individual membranes of parchment, bound together as a larger roll. ↩

- In 1627, there were two prothonotaries active in the court, Robert Heath and George Paul, whose names feature at the bottom of each rotulet. ↩

- C W Brooks, Pettyfoggers and Vipers of the Commonwealth (Cambridge, 1986). ↩

- KB 27/1554/1. Rotulets 20-22 appear to have been written by Dover, and he also appears within this section of the roll. ↩

Dear Dr Roger,

I enjoyed this post (led here by a newspaper report) very much, but I was a little surprised that you thought the play on words was confined to apples and pells, good though that is. Certainly the ebb and flow (ahem) of the gall supply, and Dover’s obvious joie de vivre, are the most interesting things about the poem, but there is another pun in there: he uses the word ‘painted’ which is little off-beam for calligraphy, but allows him to talk about the unavailability of ‘Apelles’ who was the most famous of Ancient Greek painters, a nice mock-heroic touch, worthy of a known admirer (and even taker-off) of the Greeks. Worth a mention?

Yours sincerely…

Hello David. I agree with you that he is probably also referring to Apelles the painter here. I decided to focus on the (gall) apple pun in particular, but there are certainly many more layers to the poem (a further possibility being a link to the name ‘Paule’, one of the prothonotaries whose name was written by Dover at the foot of each rotulet, or possibly even the word ‘appeals’ – a legalistic joke perhaps?). Thanks for your interest, and your comment! Euan

Dear Euan,

I don’t see any evidence in the poem that Dover is punning: the reference to Apelles is a commonplace in European writings over several centuries, made whenever an allusion to perfection in painting is required. It’s quite a stretch to get “apples”, and then oak galls, from the clearly written “Apelles”, and an even greater stretch to get the Latin word for animal skins. Perhaps the mistake arises from a misreading of “Apelles” in one instance as “As pelles”? It’s a pity the national press has repeated the error.

Dear Derek,

While I agree with you that the reference here to Apelles is clear, I’m afraid I do not agree that this is Dover’s only possible meaning. Gall apples, Latin (the language in which these documents were written) and the term ‘pells’ would all have been familiar to Dover. Indeed, the Pell Office (an Exchequer office, with its officer, the Clerk of the Pells) was situated in the direct vicinity of King’s Bench at Westminster, while you will find reference to gall apples as a commodity for ink throughout the previous centuries. Certainly, the roll from the previous term shows evidence for sub-standard ink throughout which lends credence to the suggestion of gall apples. While I agree that the word(s) which I have rendered ‘As pelles’ may be subject to different readings, it is clearly different from the other two examples of ‘Apelles’ elsewhere, and I believe is deliberately meant as such, to convey further meaning. Thank you for your interest, and your comments.

My attention has been drawn to your blog post by a fellow member of the Chipping Campden History Society. This is really exciting news! I hope it is acceptable for me to put a link to your post on our website. I am particularly interested to find out about the Plea Roll and Dover’s entries as I am researching legal cases concerning Sir Baptist Hicks, (Viscount Campden from 1628) and two brothers, Augustine and Anthony Jarrett. Robert Dover acted on Anthony’s behalf in one case and was apparently much maligned by Hicks because of it. Augustine Jarrett wrote a letter to Hicks to which Hicks took such exception that he sued for libel. All the documentation is in the National Archives (Cat. STAC8/182/24. Jarrett’s letter is a wonderful piece of rhetorical invective (a transcription can be found on the CCHS website). I haven’t discovered the outcome, but maybe there’s something in the Plea Rolls. I look forward to visiting the NA again in due course!! Thank you.

Hello Mary. You are very welcome to link to this post on your website. The cases you are looking at sound fascinating. If you want to take a look through the plea rolls, I’d recommend taking a look at our research guides to them in advance of your visit. You can find more information about these records, and how to navigate them in our research guide here. Thank you for your interest!

It gives me great joy to see such keen interest in my ancestor.. truly wonderful to see his positive vibration still finding it’s way to the surface..

‘Heroic, spriteful.. mirth making Dover.. above all the rest’ ..

I am looking forward to rereading this many times, an amazing find, the sort of thing that would have delighted Geoffrey Powell, wonderful. Be good to give the school a copy and perhaps a shortened one to sit in the 6 th form study, What a chance find and by someone who appreciated its value Sue Samuelson. ( rather old with poor memory alas)